Introduction

Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved the use of drug-eluting stents (DES) in May 2003, roughly eight million stents have been deployed worldwide and current projections indicate that by the end of 2010, greater than 4.5 million DES will be implanted per year1,2.

By releasing local anti-proliferative drugs and inhibiting neointimal hyperplasia, DES have drastically reduced the rates of restenosis compared with bare metal stents (BMS).1,2 However, the localised effects of DES lead to diversified remodelling of the vessel wall including delayed re-endothelialisation, inflammatory changes of the medial wall, and hypersensitivity reactions3. The end result is vascular remodelling that can present along a wide spectrum from late acquired stent malapposition (LSM) to frank coronary artery aneurysm formation3,4.

The development of coronary aneurysms from coronary stenting has previously been described with BMS, where aneurysm formation was linked to mechanical factors including stretch, stent fracture and dissection5,6. However recently, there have been an increasing number of reports describing coronary aneurysm formation following placement of DES, suggesting a pathophysiologic link between DES and coronary aneurysm7,8.

The incidence, clinical presentation and implications associated with the development of coronary aneurysms (CA) following DES (DESCA) are not known. Our objective was to systematically review published literature for the incidence, clinical characteristics, predictors, treatment and, outcomes of DESCA.

Methods

Search strategy

A literature search using PubMed, EMBASE, and Google Scholar was performed using the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms “Coronary artery aneurysm,” “paclitaxel,” “sirolimus,” “everolimus,” “zotarolimus,” and “drug-eluting stent” to identify case reports and case series. No language restriction was applied. Bibliographies of relevant studies and the “related articles” link in PubMed were used to identify additional studies. Published abstracts from annual meetings of the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Transcatheter Therapeutics (TCT), Society of Coronary Angiography and Intervention (SCAI) and EuroPCR were also identified. Reference lists of review articles and cited articles were used to locate additional studies. The following journals were hand-searched from January 2002 to October 2010: Heart, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, American Journal of Cardiology, American Heart Journal, Circulation, Hypertension, Circulation Research, European Heart Journal, Journal of Invasive Cardiology, and Journal of Interventional Cardiology.

Study selection

Randomised DES trials comparing DES vs. BMS were reviewed for reports of DESCA, which was defined as dilation of the coronary artery that exceeded 1.5 times the reference diameter of the adjacent angiographically normal coronary segment. This definition differed from the 1.2 times dilation used in the clinical trials. DES for treatment of de novo coronary artery aneurysms and non-coronary aneurysms were excluded.

Data extraction

Studies were selected and data were extracted independently by two reviewers (A.H. and K.K.). Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The studies were evaluated carefully for duplicate or overlapping data. Reports from collaborating groups were cross-referenced to avoid counting the same case more than once. Information on age, gender, initial indication for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), type and number of stents deployed, presenting symptoms leading to CA detection, length of time from DES to CA, location of aneurysm, use of IVUS to confirm aneurysm, and treatment regimens were recorded. Authors of the published manuscripts/abstracts were contacted for additional data regarding their patients. In addition to the number of participating patients, we recorded the following clinical and angiographic characteristics: age, gender, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. Time duration between index angiography and follow-up angiography on which DESCA was diagnosed were recorded as well as clinical follow-up rates. Raw data obtained from source information of the individual studies were used for all analyses. Guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews 5.0.1 were followed for our meta-analysis9.

Statistical analysis

Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed as summary statistics. Categorical variables were reported as percentages and continuous variables were presented as means ±standard deviation. The pooled RR was calculated with the DerSimonian-Laird method for random effects.10 To assess heterogeneity across trials, we used the Cochran Q-test based on the pooled RR by Mantel-Haenszel. Heterogeneity was also assessed by means of the I2 statistic as proposed by Higgins et al (determining the variance across groups as a result of heterogeneity instead of chance).11 Results were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Revman software version 5.0.17 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).9

Results

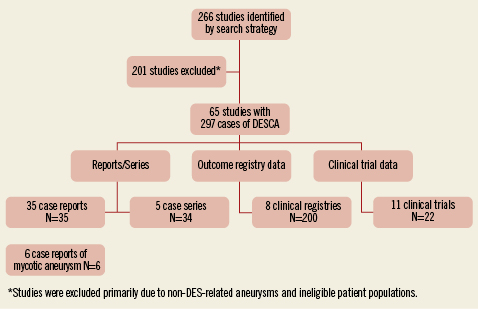

The results of our search strategy are summarised in the flow diagram (Figure1). We identified 35 case reports7,8,12-44 and five case series45-48,60 describing 51 cases of DESCA. There were six reports of mycotic /infectious aneurysms49-54. A search of the outcome registry data yielded eight studies describing 200 cases of DESCA55-62. Finally, 22 cases of DESCA were reported as adverse events in 11 clinical trials63-71.

Figure 1. QUORUM diagram.

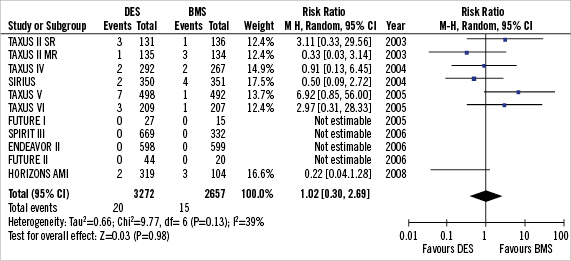

Figure 2. Forest plot of risk of DESCA in DES vs. BMS.

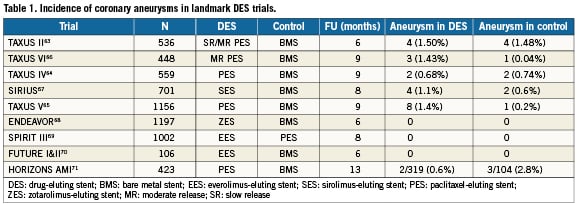

Randomised trial data (Table 1, Figure 2)63-71

Landmark clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of DES vs. BMS were individually reviewed for assessment of coronary aneurysm as an endpoint. Using this criterion, 11 clinical trials reporting 22 cases of DESCA during an angiographic follow-up of six to nine months were found63-71.

In the TAXUS II63 trial, a total of eight DESCA were identified by coronary angiography (three in the TAXUS-slow-release (SR) group, one in the SR control group, one in the TAXUS-moderate-release (MR) group, and three in the MR control group). Differences in aneurysm rates between TAXUS and control groups were not significant, and aneurysm formation was not correlated with adverse clinical events. In the TAXUS V65 randomised trial comparing SR PES to BMS, a trend toward greater late-acquired aneurysm formation was seen in patients who received PES (1.4% with PES compared to 0.2% with BMS) but this did not approach statistical significance (p=0.07). In the TAXUS VI trial66 assessing clinical and angiographic outcomes of the TAXUS MR stent in the treatment of long, complex coronary artery lesions, 9-month angiographic follow-up showed 1.4% of patients in the Taxus group developed coronary aneurysms compared to 0.5% in BMS (p=0.62). In the SIRIUS trial67, there was no statistical difference in the incidence of aneurysm formation in the SES group (1.1%) compared to BMS (0.65%). In the trials of ZES 68 and EES69,70, there were no DESCA reported in either DES or BMS groups.

Using a random effects analytic model (Figure 2), the incidence of CA in DES was 0.6% vs. 0.5% in the BMS group amongst 5,929 patients translating into a relative risk of (RR) 1.02 (95% CI 0.38-2.69; p=0.98). There was mild heterogeneity amongst trial with respect to formation of coronary aneurysms between the trials.(I²=39%; p=0.13).

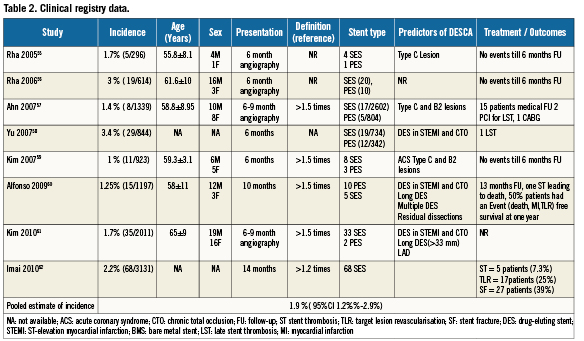

Clinical registry data (“real world”)55-62

Data were available from eight clinical registries involving 10,355 patients who underwent DES implantation55-62. DESCA occurred in 200 patients translating into a pooled weighted mean incidence of 1.9 % (95%CI 1.2%-2.9%) during a mean follow-up of 6- to 9-months in the clinical registry data. Eighty-two percent (82%) of these were in segments with SES and 18% in segments with PES. The percentage of SES vs. PES treated sites that developed an aneurysm was similar (Table 2). Thirty-four (34) patients (17%) had events (including death, MI or TLR) during the 6-13 months follow-up. There were nine cases (4.5%) of stent thrombosis during follow-up. Aneurysms appeared to occur more frequently in B2 and C type lesions than in types A and B155-57. Additionally, chronic total occlusion lesions and stenting in the setting of acute MI appeared to be independent predictors of aneurysm development.58-61

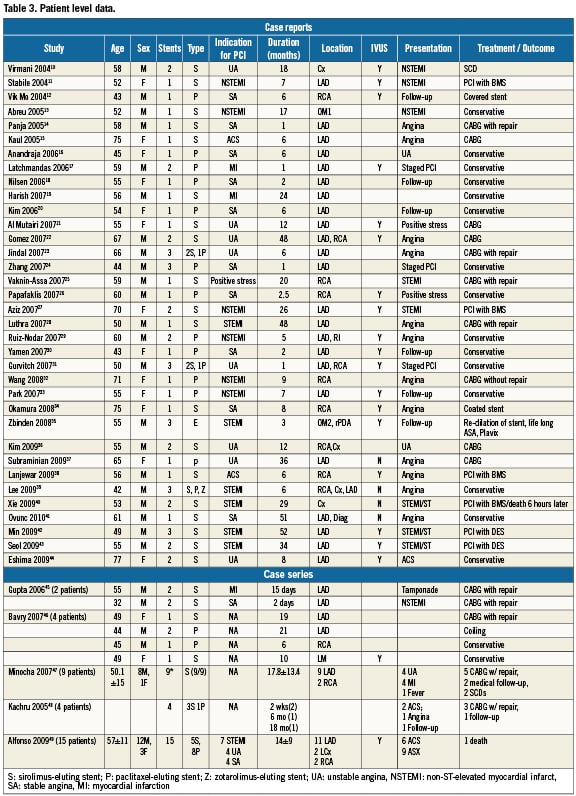

Patient level data from published reports7,8,12-44 and case series45-48,60

There were 35 case reports 7,8,12-44 (N=35) and five case series 45-48,60 (N=34) including a total of 69 patients on whom patient level data was available (Table 3). Characteristics of patients included in these reports are summarised in the table. Mean age was 55±10 years, with 69% male. The indication for DES placement included acute coronary syndrome (unstable angina/NSTEMI) in 44%, stable angina in 32%, and STEMI in 22% and abnormal stress test in 2%. Five patients (7%) died during the acute presentation during the index hospitalisation. Mean duration between DES implantation and CA was 14.2+13.7 months (95% CI 11-17.5 months).

In the case reports and case series, DESCA was seen 67% of the time in the LAD, 25% in the RCA, 12.5% in the left circumflex, 1.5% in the ramus, and 1.5% in the left main. Sixty-three percent (63%) of the reported DESCA was from SES, 34% from PES, 1.5% from ZES, and 1.5% EES. In 34 (49%) patients the diagnosis of DESCA was confirmed with IVUS. Kaplan Meyer survival analysis based on DES type did not demonstrate any significant difference between SES and PES in relation to time to development of DESCA (log rank p=0.34).

The clinical presentation of DESCA in these patients included acute MI in 20.5%, 16% presented with unstable angina (36.5% ACS) and 26% with stable anginal symptoms. Twenty-two (32%) patients underwent CABG with aneurysm excision/repair and in five patients evidence of intense inflammation was reported on surgical pathology. Three patients (8%) were treated with repeat PCI, one patient (2%) was treated with coil embolisation, and 33 (48.5%) patients were managed conservatively with dual antiplatelet therapy of which three CA subsequently resolved on follow-up angiography. Five patients (7%) died suddenly after presenting with NSTEMI before definitive treatment could be provided.

When adequate clinical data was available from case reports and series (69 patients), we used the classification scheme proposed by Aoki et al72 to categorise DESCA into three types (Table 4). Our search revealed six reports of mycotic aneurysms49-54. Mean age was 60±11 years. All the six (100%) were males. Four SES and three PES were used to cover six lesions. All patients presented with recurrent fevers and ACS. Three patients had pre-existing CKD and diabetes, and two patients had formation of intra-cardiac fistulae. Median duration between implantation and clinical presentation was two months (two days – four months). All patients had positive blood cultures for Staphylococcus aureus. Four out of six patients (67%) had pathological confirmation of mycotic aneurysms. Five out of six patients were treated with surgical excision with bypass grafting. There were two deaths (33%).

Discussion

Reports of coronary aneurysms following DES placements have been increasing and are seen not uncommonly in routine clinical practice. Because DES are the most commonly utilised stents in clinical practice it becomes important to identify the incidence, risk factors and natural history of this iatrogenic disease. Our systematic review provides the best available synthesis of available evidence in this regard.

Incidence

In the pre DES era, the incidence of coronary aneurysms ranged from 1.4-4.9%6,73-75. In the present review, the incidence of DESCA ranged from 1-3.4% in clinical registries to 0.7-1.4% in clinical trials. However, interpreting the accuracy of these values is fraught with difficulty. Firstly, in the studies we examined, the definition of CA was variable. The DES trials defined CA as a 20 % increase in vessel diameter compared to the standard definition of 50% used in the case reports and case series .Secondly, the reported incidence of DESCA in clinical trials and registries is based on “early” angiographic follow-up at 6-9 months. It is still unknown if late aneurysm formation occurs more frequently. Moreover, the diagnosis of CA in many studies was made by coronary angiography, which is merely a “luminogram” and cannot reliably discern vascular remodelling, LST, or fracture. Unlike IVUS examination, standard angiography cannot distinguish between aneurysms and pseudo-aneurysms or compare overlapping versus non-overlapping stents77-79. In our review, only 34 out of the 69 cases (49%) of DESCA were confirmed with IVUS evaluation. The importance of IVUS examination in clarifying the morphology of CA was demonstrated by Maehara et al80 who found that only one-third of the angiographically diagnosed aneurysms in 77 consecutive patients had the IVUS appearance of a true or pseudoaneurysm. Instead, most angiographically diagnosed aneurysms had the morphology of complex plaques or normal segments with adjacent stenosis. Lastly, in many landmark DES trials there was simply no mention of the incidence of DESCA. These factors further complicate the issue of “true” incidence of DESCA. However, based on our meta-analysis, the weighted pooled incidence appears to be in the order of 0.6% (95% CI 0.4%-0.9%) [RCTs] to 1.9 % ( 95% CI 1.2%%-2.9%) [registries] at a mean follow-up of nine months.

Classification

In an attempt to organise DESCA into various categories, a novel classification system has been proposed by Aoki et al72 (Table 4) that characterises coronary aneurysms based on aetiology and clinical course. TypeI DESCA occur immediately (within one month) of stent placement. Pathophysiology is similar to that seen in early reports involving BMS with arterial injury from mechanical factors such as stretching, stent fracture, dissection, and haematoma4-7. Type II DESCA occurs sub acutely, usually from 6-9 months, and is felt to be secondary to arterial wall response to the DES. Specific to DES, this was the most common type of aneurysm in the reported series and clinical trials. Type III DESCA refers to infectious mycotic aneurysms.

Pathophysiology of Type II DESCA

Several features unique to DES have been proposed to contribute to the formation of CA late after implantation. Both sirolimus and paclitaxel are potent anti-mitotic agents which inhibit cell cycle progression and thereby inhibit neo-intimal hyperplasia. However, it is this same anti-proliferative effect which has been proposed as increasing the risk of CA3,5,10. In fact, Rab et al5 reported that using anti-inflammatory agents such as glucocorticoids and colchicine after stent placement could increase the risk of CA. Within this model, the inhibition of neointimal proliferation and delay in intimal healing may lead to weakening of the arterial wall and thus aneurysm formation. Pathologic analysis of aneurysms revealing intense eosinophilia with a dominant T-lymphocytic infiltrate suggests that localised hypersensitivity may lead to aneurysm formation. First reported by Virmani et al, localised inflammation at aneurysm sites has also been noted in other case reports10,15,28,45,46. Among the three components of DES –metal, polymers, and drug– non-erodible polymers have been proposed as antigenic stimuli. Due to the paucity of data involving eosinophilic infiltrates caused by BMS and pharmacokinetic data revealing undetectable sirolimus levels within the arterial wall after 60 days, Virmani et al7 proposed that non-erodible polymers such as polyethylene-vinyl acetate and poly-n-butyl methacrylate serve as the key players inciting this inflammatory response. In sensitive patients, the intense eosinophilic infiltration would lead to vessel wall remodelling, destruction of the medial wall, and aneurysm formation3,10. Zbinden et al35 recently reported the first case of CA with EES. They found that even with second-generation DES which have amore biocompatible polymer, there can be adverse reactions to the polymer and/or to the drug, leading to aneurysm formation with possible late stent thrombosis.

Clinical presentation and outcomes

As summarised in this study, CA have varied clinical presentations. In the case reports and series of CA associated with DES placement, 62.5% of the 69 patients presented with ACS or angina, and there were five cases (7%) of cardiac death during the index hospitalisation. In contrast, in registries55,56,58 and clinical trials63-71 there was not an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular endpoints (MACE) in patients with DESCA, similar to pre-DES data.6,74

Risk factors

Among various clinical predictors studied, DES for CTO, complex lesions (Type B and C2)55,57 and stenting in primary PCI appear to portend an increased risk for CA formation58-61. In their study evaluating the efficacy of PES in CTO lesions, Werner et al found that in three of 48 patients (6%), there was a moderate increase of luminal diameter at 6-month angiographic follow-up. The increase in lumen size did not reach angiographic criteria for CA; however, they did not perform IVUS, which could have better clarified the morphology87.

Implications

Reports regarding DESCA are still emerging, but our systematic review of the available evidence suggests that CA may not be just a sporadic but a systemic problem with DES. While the pooled incidence in our systematic review has been between 0.6%-1.9% this value takes on added significance when seen in the larger context of the over 2.5 million PCIs every year and the over nine million DES that have been deployed since 2003. Another notable finding in our search was the number of cases of DESCA seen in East Asian and South Asian populations, suggesting possible racial and ethnic differences in vascular response to DES implantation. This apparent increased number may be secondary to the higher prevalence of prior Kawasaki’s disease in Asians with resultant intrinsic changes in coronary vasculature.88

There are no clear guidelines in the treatment of DESCA – various methods employed in case reports include observation, dual antiplatelet therapy, coiling, and surgical excision. One study reported use of a pericardial patch to repair a coronary aneurysm28.

Aoki and colleagues72, proposed “individualised” therapy, using a combination of aneurysm size, expansion history, pathophysiology, and symptoms to decide which therapy alternatives to apply, if any. This approach is both reasonable and necessary without trial data to guide CA management for Type I&II. DESCA appears to predispose to stent thrombosis and it appears reasonable to suggest long-term and perhaps indefinite DAPT in such patients. Importantly, every effort should be made to further define aneurysmal segments using IVUS.

Owing to the catastrophic consequences of DES infection, a high index of suspicion is warranted. In this setting, immediate confirmation of diagnosis, either by invasive or non-invasive techniques, and an urgent aggressive management is required. Therefore, if an infected Type III coronary aneurysm is detected, prompt surgical excision of the stent and debridement of infected tissues is recommended to minimise the risk of rupture, cardiac tamponade and sudden death.

Optimal patient selection and stent size for DES as well as ensuring appropriate stent apposition at the time of deployment all could potentially curtail the risk of DESCA. Additionally, if patients are found to have diseased segments of the coronary vasculature that are ecstatic or aneurismal, it would be advisable to not use DES under those circumstances.

Limitations

Our systematic review has several limitations, fundamentally those inherent to primary studies. As CA has recently been recognised as a potential complication of DES, literature is limited and very heterogeneous. Although every effort was made to gather as much information about cases and studies, data was incomplete and hence meaningful statistical inferences could not be drawn. Biased selection of reported patients was very likely in our case reports. Moreover, only 33% of case reports confirmed aneurysm formation with IVUS examination. There was no standardised definition of CA. Moreover, most of the landmark clinical trials did not even mention coronary aneurysm let alone set it as a pre-specified endpoint.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that coronary artery aneurysms after DES implantation are a relatively rare complication with variable clinical outcomes; however, when put into the context of several million such stents being placed annually, the clinical and economic impact becomes substantial. Systematic evaluation of DESCA including potential mechanisms, long-term risk, and appropriate management still need investigation. A standardised definition of and diagnostic approach to CA, including IVUS confirmation, is needed. A thorough review of major DES trials with careful long-term follow-up of patients receiving DES is also warranted.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.