Abstract

Background

Recent support for centralization of complex operations, such as pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), is based on surgeon-specific volume–outcome relationships. This study examined whether volume of anatomically related operations (operative mix), besides PD, is also independently associated with postoperative outcomes after PD.

Methods

The study queried the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (2004–2009) for surgeons performing PD. Operative mix (OM) was defined as the year-specific number of other pancreatic, hepatic, biliary, and gastric operations performed by individual surgeons. Regression models included surgeon and hospital PD volume, adjusted for other hospital- and patient-specific factors.

Results

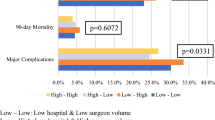

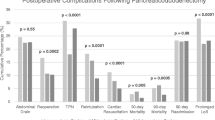

Among 1747 surgeons, 88.3% had low PD volume (≤ 5 cases/year), 8.9% had moderate PD volume (6–16 cases/year), and 2.8% had high PD volume (≥ 17 cases/year). Low-PD-volume surgeons with high OM (≥ 21 cases/year) (4.4%), moderate-PD-volume surgeons with high OM (3.4%), and high-PD-volume surgeons with high OM (2.7%) each had lower mortality than low-PD-volume surgeons with low OM (9.3%; all p ≤ 0.02). The frequency of prolonged hospitalization among low-PD/high-OM surgeons (45.3%) was lower than among low-PD/low-OM surgeons (61.6%; p < 0.001). Increasing OM volume was associated with decreased inpatient mortality, shorter hospital stay, and lower likelihood of any postoperative complication, using unadjusted regression (all p < 0.001). Adjusted regression results indicated that increasing OM volume is a significant predictor of decreased odds of a prolonged hospital stay (odds ratio [OR] 0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–0.90; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Surgeon PD volume is an important predictor of outcomes after PD. However, surgeon OM volume identifies a subset of lower-PD-volume surgeons with more favorable outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, Stukel TA, Lucas FL, Batista I, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. NEJM. 2002;346:1128–37.

Finlayson EV, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital volume and operative mortality in cancer surgery: a national study. Arch Surg. 2003;138:721–25.

Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA, Lipsett PA, Stanley JC, Upchurch GR. Variation in postoperative complication rates after high-risk surgery in the United States. Surgery. 2003;134:534–41.

Reames BN, Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital volume and operative mortality in the modern era. Ann Surg. 2014;260:244–51.

Fong Y, Gonen M, Rubin D, Radzyner M, Brennan MF. Long-term survival is superior after resection for cancer in high-volume centers. Ann Surg. 2005;242:540–4.

Hata T, Motoi F, Ishida M, Naitoh T, Katayose Y, Egawa S, et al. Effect of hospital volume on surgical outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2016;263:664–72.

Boudourakis LD, Wang TS, Roman SA, Desai R, Sosa JA. Evolution of the surgeon-volume, patient-outcome relationship. Ann Surg. 2009;250:159–65.

Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals: HHS efforts to improve US health care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:897–9.

Schneider EB, Hyder O, Wolfgang CL, Dodson RM, Haider AH, Herman JM, et al. Provider versus patient factors impacting hospital length of stay after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2013;154:152–61.

Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, Sharp SM, Warshaw AL, Fisher ES. Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1999;125:250–6.

Birkmeyer JD. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–27.

Enomoto LM, Gusani NJ, Dillon PW, Hollenbeak CS. Impact of surgeon and hospital volume on mortality, length of stay, and cost of pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:690–700.

Toomey PG, Teta AF, Patel KD, Ross SB, Rosemurgy AS. High-volume surgeons vs high-volume hospitals: are best outcomes more due to who or where? Am J Surg. 2016:211:59–63.

Al-Refaie WB, Muluneh B, Zhong W, Parsons HM, Tuttle TM, Vickers SM, et al. Who receives their complex cancer surgery at low-volume hospitals? J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:81–7.

Chang DC, Zhang Y, Mukherjee D, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD, Cameron JL, et al. Variations in referral patterns to high-volume centers for pancreatic cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;109:720–26.

Riall TS, Eschbach KA, Townsend C, Goodwin JS. Trends and disparities in regionalization of pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1242–52.

Epstein AJ, Gray BH, Schlesinger M. Racial and ethnic differences in the use of high-volume hospitals and surgeons. Arch Surg. 2010;145:179–86.

Liu JH, Zingmond DS, McGory ML, SooHoo NF, Ettner SL, Brook RH, et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA. 2006;296:1973–80.

Massarweh NN, Flum DR, Symons RG, Varghese TK, Pellegrini CA. A critical evaluation of the impact of Leapfrog’s evidence-based hospital referral. J Am Coll Surg. 2011; 212:150–59.

Sachs TE, Ejaz A, Weiss M, Spolverato G, Ahuja N, Makary MA, et al. Assessing the experience in complex hepatopancreatobiliary surgery among graduating chief residents: is the operative experience enough? Surgery. 2014;156:385–93.

Sachs TE, Pawlik TM. See one, do one, and teach none: resident experience as a teaching assistant. J Surg Res. 2015;195:44–51.

Bellal J, Morton JM, Hernandez-Boussard T, Rubinfeld I, Faraj C, Velanovich V. Relationship between hospital volume, system clinical resources, and mortality in pancreatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:520–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1: ICD-9 Codes for Operative Mix Operations

Appendix 1: ICD-9 Codes for Operative Mix Operations

Other pancreatic operations, exclusive of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), included 52.6, 52.51, 52.59, 52.52, 52.53, and 52.5. The ICD-9 codes for bile duct operations included 51.79, 51.39, 51.14, 51.36, 51.39, 51.41, 51.42, 51.43, 51.49, 51.51, 51.59, 51.61, 51.62, 51.63, 51.69, 51.71, 51.72, 51.79, 51.81, 51.82, 51.92, 51.93, and 51.94. The ICD-9 codes for hepatic operations included 50.0, 50.22, 50.29, 50.3, and 50.4. The ICD-9 codes for gastric operations included 43.9, 43.91, 43.99, 43.5, 43.6, 43.7, and 43.8.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hachey, K., Morgan, R., Rosen, A. et al. Quality Comes with the (Anatomic) Territory: Evaluating the Impact of Surgeon Operative Mix on Patient Outcomes After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 25, 3795–3803 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6732-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-018-6732-y