Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate the psychological, socio-behavioral, and medical implications of apparently false-positive prostate cancer screening results.

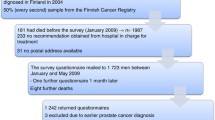

METHODS: One hundred and twenty-one men with a benign prostate biopsy performed in response to a suspicious screening test (biopsy group) and 164 men with a normal prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test result (normal PSA group) responded to a questionnaire 6 weeks, 6 and 12 months after their biopsy or PSA test.

RESULTS: The mean (±SD) age of respondents was 61±9 years (range, 41 to 88 years). One year later, 26% (32/121) of men in the biopsy group reported having worried “a lot” or “some of the time” that they may develop prostate cancer, compared with 6% (10/164) in the normal PSA group (P<.001). Forty-six percent of the biopsy group reported thinking their wife or significant other was concerned about prostate cancer, versus 14% in the normal PSA group (P<.001). Medical record review showed that biopsied men were more likely than those in the normal PSA group to have had at least 1 follow-up PSA test over the year (73% vs 42%, P<.001), more likely to have had another biopsy (15% vs 1%, P<.001), and more likely to have visited a urologist (71% vs 13%, P<.001).

CONCLUSION: One year later, men who underwent prostate biopsy more often reported worrying about prostate cancer. In addition, there were related psychological, socio-behavioral, and medical care implications. These hidden tolls associated with screening should be considered in the discussion about the benefits and risks of prostate cancer screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Harris R, Lohr KN. Screening for prostate cancer: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:917–29.

Sirovich BE, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Screening men for prostate and colorectal cancer in the United States: does practice reflect the evidence? JAMA. 2003;289:1414–20.

Stamey T, Caldwell M, McNeal J, Nolley RMH, Down J. The prostate specific antigen era in the United States is over for prostate cancer: what happened in the last 20 years? J Urol. 2004;172:1297–301.

McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler F, Caubet J, et al. Psychological effects of a suspicious prostate cancer screening test followed by a benign biopsy result. Am J Med. 2004;117:719–25.

Essink-Bot ML, de Koning HJ, Nijs HG, Kirkels WJ, van der Maas PJ, Schroder FH. Short-term effects of population-based screening for prostate cancer on health-related quality of life. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:925–31.

Gustafsson O, Theorell T, Norming U, Perski A, Ohstrom M, Nyman CR. Psychological reactions in men screened for prostate cancer. Br J Urol. 1995;75:631–6.

Taylor KL, DiPlacido J, Redd WH, Faccenda K, Greer L, Perlmutter A. Demographics, family histories, and psychological characteristics of prostate carcinoma screening participants. Cancer. 1999;85:1305–12.

Cantor SB, Volk RJ, Cass AR, Gilani J, Spann SJ. Psychological benefits of prostate cancer screening: the role of reassurance. Health Expect. 2002;5:104–13.

Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Boyce A, Jepson C, Engstrom PF. Psychological and behavioral implications of abnormal mammograms. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:657–61.

Gram IT, Lund E, Slenker SE. Quality of life following a false positive mammogram. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:1018–22.

Lidbrink E, Elfving J, Frisell J, Jonsson E. Neglected aspects of false positive findings of mammography in breast cancer screening: analysis of false positive cases from the stockholm trial [see comments]. BMJ. 1996;312:273–6.

Ellman R, Angeli N, Christians A, Moss S, Chamberlain J, Maguire P. Psychiatric morbidity associated with screening for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1989;60:781–4.

Lafata J, Simpkins J, Lamerato L, Poisson L, Divine G, Johnson C. The economic impact of false-positive cancer screens. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2126–32.

Ford M, Havstad S, Demers R, Johnson C. Effects of false-positive prostate cancer screening results on subsequent prostate cancer screening behavior. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:190–4.

Schwartz L, Woloshin S, Fowler F Jr, Welch H. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291:71–8.

Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, Woolf SH. Breast cancer screening: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:347–60.

Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, Lohr KN. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:132–41.

Roehrborn CG, Pickens GJ, Sanders JS. Diagnostic yield of repeated transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsies stratified by specific histopathologic diagnoses and prostate specific antigen levels. Urology. 1996;47:347–52.

Djavan B, Zlotta AR, Ekane S, et al. Is one set of sextant biopsies enough to rule out prostate cancer? Influence of transition and total prostate volumes on prostate cancer yield [in process citation]. Eur Urol. 2000;38:218–24.

Levine MA, Ittman M, Melamed J, Lepor H. Two consecutive sets of transrectal ultrasound guided sextant biopsies of the prostate for the detection of prostate cancer. J Urol. 1998;159:471–5; Discussion 75–6.

Djavan B, Ravery V, Zlotta AR, et al. Prospective evaluation of prostate cancer detected on biopsies 1, 2, 3, and 4: when should we stop? J Urol. 2001;166:1679–83.

Volk R, Cantor S, Cass A, Spann S, Weller S, Krahn M. Preferences of husbands and wives for outcomes of prostate cancer screening and treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:339–48.

Volk R, Cantor S, Spann S, Cass A, Cardenas M, Warren M. Preferences of husbands and wives for prostate cancer screening. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:72–6.

Ransohoff D, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler F Jr. Why is prostate cancer screening so common when the evidence is so uncertain? A system without negative feedback. Am J Med. 2002;113:663–9.

Wilt T, Partin M. Reducing psanxiety: the importance of noninvasive chronic disease management in prostate cancer detection and treatment. Am J Med. 2004;117:796–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Dr. Barry is a consultant for the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision-Making (a 501 (c) 3 not for profit foundation).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fowler, F.J., Barry, M.J., Walker-Corkery, B. et al. The impact of a suspicious prostate biopsy on patients’ psychological, socio-behavioral, and medical care outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 21, 715–721 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00464.x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00464.x