Abstract

Liposarcoma is rare in the oral and salivary gland region (OSG), previously described in only case reports and two small series. Clinicopathologic features of a large series of these tumors were studied. Cases coded as “liposarcoma or lipoma” from 1970 to 2000 were searched for in our files. Inclusion required an OSG location and diagnosis by established soft tissue criteria. Dermal, other soft tissue, and intraosseous liposarcomas were excluded. Clinical and pathologic material was reviewed and follow-up obtained. Eighteen liposarcomas were included: 10 from males and 8 from females. The median patient age was 51 years (range, 30–70 years). Specific anatomic locations included buccal mucosa (n = 7), tongue (n = 4), parotid gland (n = 3), soft tissue overlying the mandible (n = 2), and one each of palate and submandibular gland. The average tumor size was 4.2 cm (range, 1.5 to 6.0 cm). Histologically, most tumors were well differentiated, including one atypical lipoma (n = 10), followed by myxoid (n = 5) and dedifferentiated (n = 3). OSG liposarcomas of all subtypes had increased numbers of lipoblasts. All patients were treated with surgical excision alone. Follow-up on 15 patients (83%) over a mean of 16.5 years (range, 2 to 53 years) revealed that three patients had between one and six local recurrences over periods of 18 months to 6 years. Twelve patients were without recurrence, with a mean follow-up of 12.8 years (range, 2–23 years). No patients, including those with dedifferentiated liposarcoma, had metastases or died of disease. OSG liposarcomas are rare tumors of adults, occurring most commonly in the buccal mucosa, tongue, and then parotid gland. There were no pleomorphic liposarcomas in this series; well-differentiated liposarcoma was the most common subtype, which can locally recur but, even with high-grade dedifferentiation, does not necessarily predict poor outcome. Therefore, OSG liposarcomas have better prognosis than liposarcoma in other soft-tissue locations, perhaps based on smaller size at presentation. Complete local excision and careful patient follow-up, without adjuvant therapy, appears to be the best treatment for OSG liposarcoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Liposarcomas, although common in soft tissue, are rare in the oral and salivary gland region. To our knowledge, mainly case reports (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19) and only two small series (20, 21) describe liposarcoma in the oral region. This study reviews a large number of oral and salivary gland liposarcomas. We emphasize specific sites, histologic subtypes, and tumor behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Registry of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington, D.C. from 1970 to 2000 was reviewed for cases coded as “liposarcoma” and “lipoma.” Inclusion required an oral or salivary gland location and diagnosis by established soft tissue criteria for liposarcoma subtypes, including widened fibrous septa and lipocytic atypia for well-differentiated liposarcoma, lipoblasts, delicate vasculature, and myxoid background for myxoid liposarcoma and ≥10× power field (2 mm) of alipogenic spindled areas adjacent to areas of well-differentiated liposarcoma for dedifferentiated liposarcoma, as per the new World Health Organization classification for soft tissue tumors (in press, 2002) and the most recent published soft tissue criteria (22). The slides and clinical information on 26 cases were reviewed. Eight tumors were excluded from the current study: one because of its intraosseous location within the maxillary sinus, two because the provided slides did not show sufficient atypia to warrant a diagnosis of malignancy, and five that were better classified as chondroid lipoma. One case had been misdiagnosed as “intramuscular lipoma” and was a well-differentiated liposarcoma with definite atypia. One of our tumors was reclassified as “atypical lipoma” because of its superficial location; the remaining 17 cases were intramuscular or intraglandular. Follow-up information was obtained from the patients’ medical records, contributing physicians, local or national tumor registries, or occasionally, the patients themselves.

RESULTS

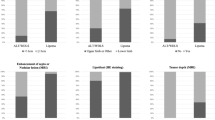

Clinical

The clinicopathologic features and follow-up of the 18 included liposarcomas are summarized in Table 1. Tumors were from 10 men and 8 women. The median patient age was 51 years (range, 30–70 years). The mean duration of tumor before excision was 3.6 years (43 months; range, 3–144 months). Clinical symptoms included recently enlarged mass. Additionally, two patients had prior malignant breast tumors removed; one patient had concomitant chronic sialadenitis, and one patient had a draining abscess related to the tumor. Specific anatomic locations for the liposarcomas included the buccal mucosa (n = 7), tongue (n = 4), parotid gland (n = 3), soft tissue overlying the mandible (n = 2), and one each of the palate and submandibular gland.

Pathology

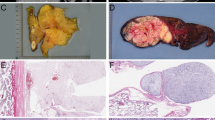

The average size of tumor was 4.2 cm (range, 1.5 to 6 cm). Grossly, tumors were solid, tan-gray, and multilobulated. Several appeared well circumscribed and partially encapsulated. The other tumors were less well delineated and more diffusely infiltrating. The cut surface varied from greasy to mucoid and gelatinous.

Histologically, most tumors were well differentiated (n = 10), including one that was reclassified as “atypical lipoma” because of its superficial location, and these were found in all locations. Next most common was myxoid (n = 5) and then dedifferentiated (n = 3, including one low-grade tumor of the tongue and two high-grade tumors of the parotid and buccal mucosa).

The well-differentiated tumors (Fig. 1) were composed of lobules of mature fat, with thickened or widened fibrous septa and scattered atypia. The atypical nuclei were large, hyperchromatic, and prominent even at lower magnification. The two well-differentiated tongue liposarcomas had easily identifiable lipoblasts (Fig. 2), some with uni- or bivacuolization. Two tumors were considered the sclerosing variant of well-differentiated liposarcoma, based on a dense collagenous background matrix along with mature fat and scattered atypia; one of these two cases was reclassified as an atypical lipoma based on its superficial buccal mucosa location (Fig. 3). Nine well-differentiated liposarcomas were all intramuscular or intraglandular.

The myxoid liposarcomas had a nodular growth pattern, myxoid background, delicate plexiform capillary network, and increased lipoblasts, predominantly univacuolated (Fig. 4) and rarely with a sinusoidal growth pattern. None of the cases in our study demonstrated round cell subtype. One of the cases resembled a myxoid lipoblastoma, with increased septation, yet this tumor was in an adult and had features otherwise typical of myxoid liposarcoma including myxoid background, delicate plexiform capillaries, and univacuolated lipoblasts (Fig. 5). The tongue tumor also had increased uni- and bivacuolated lipoblasts, different from myxoid liposarcoma in other sites (Fig. 6).

Three tumors were classified as dedifferentiated liposarcomas. Case 5, arising in the tongue, was a low-grade, dedifferentiated liposarcoma, with a >10× power field of alipogenic areas of relatively histologically bland spindled proliferation and scattered floret cells, that was adjacent to typical lipoma-like well-differentiated liposarcoma. Case 12, of the buccal mucosa, had well-differentiated liposarcoma adjacent to spindled pleomorphic liposarcoma-like areas, including alipogenic areas and concomitant myxoid areas (Fig. 7). Like the well-differentiated and myxoid liposarcomas of the tongue, above, this tumor also showed a focal increase in lipoblasts over that seen in liposarcomas in other anatomic locations. Finally, a parotid lesion, Case 15, was an intermediate- to high-grade MFH-like dedifferentiated liposarcoma with spindled atypical cells, atypical mitoses, pleomorphic multinucleated, floret-like cells and adjacent typical well-differentiated liposarcoma.

High-grade dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the buccal mucosa with increased lipoblasts in all components (A). This tumor had foci myxoid areas (left) and alipogenic dedifferentiated areas (right), whereas adjacent well-differentiated liposarcoma was also present (not pictured). Higher magnification revealed that even the high-grade dedifferentiated area had increased lipoblasts within parts of it; these were not the pleomorphic lipoblasts of pleomorphic liposarcoma (B).

Site-Specific Characteristics

The tumor locations and subtypes are listed in Table 2. The seven buccal mucosa liposarcomas occurred more often in men than women (5:2), with a mean age of occurrence of 52.6 years. Two tumors were on the right, three on the left, and two were of unknown side. Well-differentiated liposarcoma, including one atypical lipoma, was the most common subtype (n = 4), followed by myxoid liposarcoma (n = 2) and a high-grade dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

Liposarcomas of the tongue (n = 4) affected men and women equally, with a mean age of 50 years. Of the four tumors, two tumors were histologically well differentiated; one was a myxoid liposarcoma, and one was a low-grade, dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

The parotid region was the site of three liposarcomas, with a male to female ratio of 1:2 and a mean age of 60.3 years. Two tumors occurred on the left, and one was of unknown side. Subtypes included well differentiated (n = 1), myxoid (n = 1), and high-grade, dedifferentiated (n = 1). These parotid lesions were intraglandular, leaving only focal residual ducts and acini within the tumor (Fig. 4). In contrast, the submandibular well-differentiated liposarcoma surrounded and pushed into interlobular septa of the submandibular gland but left the glandular architecture otherwise intact (Fig. 1).

Two tumors occurred in males in the soft tissue overlying the mandible. The mean age was 53 years. Histologically, there was one each of the well-differentiated and myxoid subtypes.

Tumors involving the palate and submandibular gland occurred in young women, 36 and 30 years, respectively. Both tumors were histologically classified as well-differentiated liposarcomas; the tumor in the palate was the sclerosing variant.

Clinical Follow-Up

Follow-up and clinical information on the 18 liposarcomas is presented in Table 1. Follow-up information was obtained on 15 patients (83%) over a mean period of 16.5 years (range, 2 to 53 years). Three patients (two with well-differentiated tumors, of buccal mucosa and the submandibular gland, and one with high-grade dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the buccal mucosa) had between one and six known local recurrences between 18 months and 6 years. Twelve patients were without recurrence over a mean follow-up period of 12.8 years (range, 2–23 years). Two patients died of unrelated causes at 12 and 21 years of follow-up. No patients, including the dedifferentiated liposarcoma patients, had metastases or died of liposarcoma. Tumors with recurrence were generally ≥5.0 cm in maximal diameter, despite low or high grade.

DISCUSSION

Liposarcomas of the oral and salivary gland area are rare tumors. Although liposarcoma is one of the most common soft tissue sarcomas, arising mainly in the trunk and extremities of adults (1, 22), it is rare in the head and neck region (23) and even less common in sites of the oral and maxillofacial region (20). In our experience at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the incidence for oral and salivary gland liposarcoma compared with all liposarcomas from 1970 to 2000 is 0.3% (18/5435). In the literature, Zheng and Wang (20) appeared to have the largest reported series of maxillofacial liposarcoma, yet 5 of the 10 cases would have been excluded from the present series because of their dermal or intraosseous location. Minic (21) reported four patients with intraoral liposarcomas consistent with our inclusion criteria. Golledge et al. (23) reported 76 patients with head and neck liposarcomas, 8 from oral locations, but these were a compilation of the literature and did not represent a new series studied by the authors. To date, there are approximately 45 reported cases of oral liposarcomas (1, 24); salivary gland liposarcomas are largely not included in these reports. In this study, we review histologic features and clinical correlation of a large series of oral and salivary gland liposarcomas.

There were no cases in children in our series; this finding confirms that of the literature (1, 2). Although Zheng and Wang (20) reported three cases of liposarcoma in patients between 10 and 20 years old in their series, they do not give case site–specific data. Therefore, these younger patients may have had lesions in the facial subcutis, maxilla, or mandible rather than in the oral or salivary gland area. Clinically, liposarcoma of the oral and maxillofacial region, as in other anatomic locations, is a tumor of adulthood (22). The mean age is the 6th decade, both in the literature and in this review. There does not appear to be a site or histologic predilection for oral and salivary gland liposarcoma based on age. There was a slight male predominance in our series. Most of the literature also described a slight male predominance (1, 2, 3, 4), with the exception of the Zheng series (20).

The buccal mucosa is the most common anatomic site in this series, representing 7 of 18 patients. Dominiguez et al. (5), Charnock et al. (6), Kamikaidou et al. (2), and Sadeghi and Sauk (7, 8) reported well-differentiated liposarcomas in this buccal mucosal region. Others have previously observed myxoid types in this area (4, 8). Although two reported cases in the buccal mucosa of myxoid (4) and unknown subtype (20) had local recurrence and death due to disease, others (5, 6, 10) have reported good outcome. Even a pleomorphic liposarcoma of the buccal mucosa, described by Eidinger et al. (25), that extended into the parotid secondarily did well. Our six cases of buccal mucosa liposarcoma (subtypes well differentiated, including one atypical lipoma [n = 3]; myxoid [n = 2]; and high-grade dedifferentiated [n = 1]) with follow-up all had a good overall outcome, even in the two patients with local recurrences. Therefore, buccal mucosa liposarcomas, regardless of subtype, tend to behave better than liposarcomas in nonoral locations.

Similarly, in the literature, floor-of-mouth well-differentiated liposarcomas also did well (11). None of our tumors are from this location. We do have two cases about which we are uncertain of the exact anatomic location. Case 9 is noted in the record as left mandibular soft tissue but without specification of facial or lingual aspect. Case 11 also is noted as “soft tissue overlying mandible and attached to periosteum” but without specification of facial or lingual surface. Neither case showed histologic evidence of origin from bone, skin, or subcutaneous tissue. Therefore, we included these cases as soft tissue overlying mandible but are unable to compare the good outcome of these patients to the outcomes in the literature.

The tongue, also an intramuscular location, is the second most common site of liposarcoma in this study, represented by 4 of 18 patients. Histologic subtypes include well differentiated (two) and one each of myxoid and low-grade dedifferentiated. The literature discussed tongue liposarcomas as well differentiated (12, 13, 14), myxoid (1, 3, 21), and pleomorphic subtypes (25). Most well-differentiated and myxoid subtypes had excellent overall outcome (3, 16, 21), despite occasional local recurrences (14, 15). All four of our patients with tongue liposarcomas with up to 16 years follow-up are without recurrences or metastases.

Intraparotid location accounts for three tumors in this series, one each of well-differentiated, myxoid, and high-grade dedifferentiated. Patients with the well-differentiated and even the high-grade dedifferentiated tumor, with up to 17 years follow-up, did well. Zheng et al. (20) also reported three parotid liposarcomas, subtypes not specified, all of which were without recurrence, metastasis, or death. One of our tumors is submandibular. This well-differentiated liposarcoma recurred at 6 years, but the patient has no evidence for metastasis or death, over 53 years of follow-up. Minic (21) also reported two submandibular liposarcomas, a well-differentiated and a pleomorphic one. As might be expected, the well-differentiated liposarcoma patient did well, and the pleomorphic liposarcoma patient died of disease.

The most common histologic subtype in our series, present in all oral locations, is well-differentiated liposarcoma. Only two of seven patients (29%) with well-differentiated liposarcoma have recurrences, and all patients have long survivals, with up to 53 years of follow-up. These findings generally agree with those of well-differentiated liposarcomas reported in the literature in the buccal mucosa (2, 6), submandibular region (21), and tongue that also typically have behaved well (12, 13, 14, 15). Our relatively low recurrence rate of well-differentiated atypical adipocytic tumors in oral locations varies from the figures of well-differentiated liposarcoma in the extremities and retroperitoneum, which locally recurred at rates of 50% and almost 100%, respectively, with death caused by disease in 33% of retroperitoneal well-differentiated liposarcomas (26). Similarly, oral well-differentiated liposarcomas appear to behave favorably compared with head and neck liposarcomas, the latter with an overall 50% 5-year survival (23) of all subtypes. Although we classically consider intramuscular, and in this series intraglandular, fatty tumors with atypia to be classified as “liposarcoma,” there may indeed be an argument for reclassifying atypical well-differentiated fatty tumors in oral and salivary gland locations as “atypical lipoma.” There was no difference in behavior of our tumor classified as atypical lipoma and that of many of those classified as well-differentiated liposarcoma.

Although there is only one case in the literature to our knowledge that has described dedifferentiation in oral liposarcoma (17), we observed dedifferentiation in three tumors: two high-grade tumors and one low-grade dedifferentiated tumor. In our experience and that of the literature, dedifferentiation in this location does not necessarily predict poor outcome. All such patients have done well, with prolonged survivals, and only one patient reported recurrence. Therefore, in our experience, despite high-grade dedifferentiation in this location, patients do much better than the outcome reported for dedifferentiation in nonoral locations. Soft tissue dedifferentiated liposarcomas locally recur in 41%, metastasize in 17%, and cause death from disease in 28% of cases (27).

In our series the myoid variant was the second most common liposarcoma subtype, unlike the case in other series, in which myxoid was the most common subtype (20). Interestingly, one of our myxoid liposarcomas in the buccal mucosa of a 34-year-old male has increased fibrous septa, reminiscent of lipoblastoma. This tumor has features otherwise typical of myxoid liposarcoma. None of our tumors has round cell features. All four patients with follow-up have no evidence for recurrence or metastasis, with follow-up periods up to 21 years. Based on our series and those of others (3, 5, 9, 18, 21, 23), myxoid liposarcoma of the oral cavity also tends to have a better outcome than does myxoid liposarcoma in soft tissue locations, as the latter report a metastatic rate of 23% (28).

Pleomorphic liposarcoma is uncommon in this anatomic region. In our series, none of the tumors are classified as a pure pleomorphic subtype. Although one of our high-grade dedifferentiated liposarcomas has focal areas that resemble pleomorphic liposarcoma, because of the overall observed increase in lipoblasts in oral and salivary gland liposarcomas discussed below. However, it is better classified as dedifferentiated liposarcoma with well-differentiated liposarcoma adjacent to foci of spindled alipogenic malignant fibrous histiocytoma-like areas. Pure pleomorphic liposarcoma had been reported in the oral region in the buccal mucosa (1), submandibular gland (21), and other oral sites (29, 30, 31, 32). One case in the Zheng and Wang (20) series was pleomorphic, yet the exact location of this lesion was not mentioned (possibly an intraosseous, subcutis, or dermal location). The outcome of these purely pleomorphic oral liposarcomas was poor (21, 25), unlike the multiple recurrences and yet long-time survival of our patient with high-grade dedifferentiated liposarcoma and only focal pleomorphic-like areas.

Tumor size appears to be the best predictor for recurrence. The only tumors that locally recurred in the current study, regardless of subtype, are >5.0 cm in maximal dimension. The literature also supported that size correlates with recurrence for oral liposarcomas of all subtypes. The seven oval liposarcomas described as case reports (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 16) and the three cases of oral liposarcoma in a small series (21) in the literature, including all liposarcoma subtypes, were all <5.0 cm and without recurrence, with the exception of one base-of-the-tongue well-differentiated liposarcoma that was 2.5 cm and recurred locally (14). The one case in the Minic series (21) that was >5.0 cm (10 cm) was of the pleomorphic subtype, and the patient had a poor outcome.

Lipoblasts are generally difficult to find in typical well-differentiated liposarcomas and are not common in myxoid liposarcoma or in the dedifferentiated component of well-differentiated liposarcoma. Interestingly, three of our patients with tongue liposarcomas (two well differentiated, one myxoid), one patient with the high-grade dedifferentiated buccal liposarcomas, and one patient with a well-differentiated parotid liposarcoma had increased lipoblasts. This finding is in contradistinction to the usual finding of fewer lipoblasts in liposarcomas of nonoral or nonsalivary gland locations and has not been previously reported. The awareness of increased lipoblasts in these tumors is also important in classifying the above dedifferentiated liposarcoma and distinguishing it from the pleomorphic liposarcoma subtype, which appeared in the literature to do much more poorly (21, 25) than did our dedifferentiated liposarcomas in this location. More important, awareness of an increase in lipoblasts in well-differentiated, dedifferentiated, and myxoid oral liposarcomas compared with liposarcomas in other soft tissue locations would save one from mistaking these malignant tumors for benign, heavily lipoblast-laden lesions like chondroid lipoma or even lipoblast-appearing lesions like fat atrophy. On the other hand, increased lipoblasts by itself does not necessarily mean liposarcoma, and indeed five of the tumors in our review of lesions previously classified as oral and salivary gland “liposarcoma” were reclassified by us as chondroid lipoma.

Complete local excision with careful patient follow-up appears to be the best treatment for well-differentiated, dedifferentiated, or myxoid liposarcomas of the oral region. None of our patients received adjuvant therapy, and outcomes are relatively good without metastases or death due to disease. This is supported by the literature, as there was no specific evidence that radiation therapy enhances outcome (2, 11, 19, 20, 22, 23).

In conclusion, oral and salivary gland liposarcomas most frequently occur in the buccal mucosa of adults and are most commonly well-differentiated tumors. These lesions, regardless of subtype, may have increased observable lipoblasts. The generally favorable prognosis of all subtypes, despite occasional high-grade dedifferentiation, is better than liposarcoma in soft tissue or other head and neck locations. This finding may support reclassifying some of these oral and salivary gland liposarcomas as “atypical lipoma,” especially when the tumor is <5.0 cm in maximal dimension, even if the lesion is in an intramuscular or intraglandular location.

References

Gagari E, Kabani S, Gallagher GT . Intraoral liposarcoma: case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000; 89: 66–72.

Kamikaidou N, Tadaaki K, Mishima K, Masahito S . Liposarcoma of the cheek: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 56: 662–665.

Guest PG . Liposarcoma of the tongue: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992; 30(4): 268–269.

Azaz B, Casap C . Myxoid liposarcoma of the buccal vestibule. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991; 20: 308–309.

Dominguez FV, Guglielmotti MB, Flores MC, de la Garza ML . Myxoid liposarcoma of the cheek. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 48(4): 395–397.

Charnock DR, Jett T, Heise G, Taylor R . Liposarcoma arising in the cheek: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991; 49(3): 298–300.

Sadeghi EM, Sauk JJ . Liposarcoma of the oral cavity. Clinical, tissue culture, and ultrastructure study of a case. J Oral Pathol 1982; 11(4): 263–275.

Sauk JJ . Liposarcoma of the head and neck. J Oral Surg 1971; 29: 38.

Fusetti M, Silvagni L, Eibenstein A, Chiti-Batelli S, Hueck S, Fusetti M . Myxoid liposarcoma of the oral cavity: case report and review of the literature. Acta Otolaryngol 2001; 121(6): 759–762.

Ramon Y, Horowitz Y, Oberman M, Freeman A . Liposarcoma of the buccal mucosa. Int J Oral Surg 1977; 6(4): 226–228.

Nakahara H, Shirasuna K, Terada K . Liposarcoma of the floor of the mouth: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994; 52(12): 1322–1324.

Orita Y, Nishizaki K, Ogawara T, Yamadori I, Yorizane S, Akagi H, et al. Liposarcoma of the tongue: case report and literature update. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2000; 109(7): 683–686.

Nunes FD, Loducca SV, de Oliveira EM, de Araujo VC . Well-differentiated liposarcoma of the tongue. Oral Oncol 2002; 38(1): 117–119.

Saddik M, Oldring KG, Nourad WA . Liposarcoma of the base of tongue and tonsillar fossa: a possibly underdiagnosed neoplasm. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996; 120(3): 292–295.

Wescott WB, Correll RW . Multiple recurrences of a lesion at the base of the tongue. J Am Dent Assoc 1984; 108(2): 231–232.

Nelson W, Chuprevich T, Galbraith DA . Enlarging tongue mass. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 56: 224–227.

Hasegawa H, Kawakami T, Eda S . Mixed-type liposarcoma of the oral cavity: a case with unusual features and a long survival. J Oral Pathol Med 1999; 28(3): 141–144.

Favia G, Maiorano E, Orsini G, Piattelli A . Myxoid liposarcoma of the oral cavity with involvement of the periodontal tissues. J Clin Periodontol 2001; 28(2): 109–112.

Henefer EP, Borghesani EP, Sacks FR . Liposarcoma of the cheek. J Oral Surg 1976; 34(11): 1039–1043.

Zheng JW, Wang Y . Liposarcoma in the oral and maxillofacial region: an analysis of 10 consecutive patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994; 52(6): 595–598.

Minic AF . Liposarcomas of the oral tissues: a clinicopathologic study of four tumors. J Oral Pathol Med 1995; 24(4): 180–184.

Weiss SW, Goldblum JR . Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc.; 2001.

Golledge J, Fisher C, Rhys-Evans Ph . Head and neck liposarcoma. Cancer 1995; 76(6): 1051–1058.

Nikitakis NG, Lopes MA, Pazoki AE, Ord RA, Sauk JJ . MDM2+/CDK4+/p53+ oral liposarcoma: case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001; 92(2): 194–201.

Eidinger G, Katsikeris N, Gullane P . Liposarcoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1990; 48: 984–988.

Weiss SW, Rao VK . Well-differentiated liposarcoma (atypical lipoma) of deep soft tissue of the extremities, retroperitoneum and miscellaneous sites. A follow-up study of 92 cases with analysis of the incidence of “dedifferentiation.” Am J Surg Pathol 1992; 16(11): 1051–1058.

Henricks WH, Chu YC, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW . Dedifferentiated liposarcoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 155 cases with a proposal for an expanded definition of dedifferentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 1997; 21(3): 271–281.

Kilpatrick SE, Doyon J, Choong PF, Sim FH, Nascimento AG . The clinicopathologic spectrum of myxoid and round cell liposarcoma. A study of 95 cases. Cancer 1996; 77(8): 1450–1458.

Jones JK, Baker HW . Liposarcoma of the parotid gland. Arch Otolaryngol 1980; 106: 497–499.

Amarjit S, Singh A, Hagpal BL, Gamir GS . Liposarcoma of the cheek. J Oral Surg 1978; 36: 811–813.

Adkins WY Jr, Putney FJ, Kerutner A . Liposarcoma of the maxilla: report of a case and review of the literature. Otolaryngology 1978; 86: 710–713.

Saunders JR, Jaques DA, Casterline PF, Percarpio B, Goodloe S Jr . Liposarcomas of the head and neck: a review of the literature and addition of four cases. Cancer 1979; 43: 162–168.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fanburg-Smith, J., Furlong, M. & Childers, E. Liposarcoma of the Oral and Salivary Gland Region: A Clinicopathologic Study of 18 Cases with Emphasis on Specific Sites, Morphologic Subtypes, and Clinical Outcome. Mod Pathol 15, 1020–1031 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000027625.79334.F5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000027625.79334.F5