Abstract

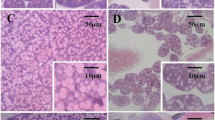

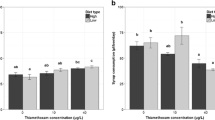

Worker honeybees (Apis mellifera carnica Polm.) were treated with imidacloprid or coumaphos. Significant effects of treatment and treatment duration were found on hypopharyngeal glands (HPG) acinus diameter (P < 0.05). Differences in the size of acini were evident in all long term (48 h and 72 h) treatments. Short term (24 h) imidacloprid treatment induced heat shock protein 70 (Hsp 70) localisation in nuclei and cytoplasm and Hsp 90 activity was found in most cell cytoplasm. Coumaphos triggered an increased level of programmed cell death, and imidacloprid induced extended necrosis in comparison to coumaphos. In 7–12 day old workers, the level of cell death after 48 hours of imidacloprid treatment was approximately 50% and increased to all cells after 72 hours. Programmed cell death remained at the normal level of approximately 10%. Our results suggest that both pesticide treatments have an influence on the reduced size of HPG and also on the extended expression of cell death.

Zusammenfassung

Arbeiterinnen der Honigbiene (Apis mellifera carnica Polm.), die in einem Brutschrank geschlüpft waren, wurden auf dem Thorax markiert und in weiselrichtige Völker gegeben. Danach wurden altersspezifische Gruppen aus jeweils acht markierten Arbeiterinnen gebildet und in Holzkäfigen gehalten. Die erste Gruppe bestand aus 1 bis 6 Tage alten Arbeiterinnen, die zweite aus 7 bis 12 Tage alten, die dritte Gruppe aus 13 bis 18 Tage alten und die vierte Gruppe aus 19 bis 32 Tage alten. Diese erhielten als Behandlung entweder: (1) eine Imidacloprid-Lösung (500 ng/kg in 35 % Zuckerwasser), (2) eine Coumaphos-Lösung oder (3) als Kontrolle 35 % (w/v) Zuckerwasser. Die Arbeiterinnen konnten diese Lösungen über 24, 48 oder 72 Stunden ad libitum aufnehmen. Am Ende der jeweiligen Behandlungsperioden wurden die Hypopharynxdrüsen dieser Bienen entnommen, fixiert und in Wachs eingebettet. Für alle Alters- und Behandlungsgruppen wurden immunhistologische Präparate angefertigt und ‘morphometrische Messungen durchgeführt, die statistisch ausgewertet wurden. Entwachste Schnitte wurden mit Primärantikörpern gegen die Hitzeschockproteine 70 und 90 (Hsp 70 und Hsp 90) inkubiert. Zelltodereignisse wurden mittels TUNEL Reagenz des ‘In situ cell death detection kit, AP’ (Roche) erfasst. Als zweites Detektionsverfahren für Zelltod verwendeten wir das Apop Tag in situ Apoptosis detection kit (Chemiocon). Damit erfassten wir die Prozentsätze an Zellen, die behandlungsbedingten Zelltod oder Hitzeschockproteine aufwiesen. Wir konnten signifikante Unterschiede im Acinus-Durchmesser der Drüsen in Abhängigkeit von der Behandlung und der Behandlungsdauer erkennen, wobei die Unterschiede in der Acinus-Größe vor allem bei den Langzeitbehandlungen (48 und 72 Std.) deutlich waren. Bei der Kurzzeitbehandlung (24 Std.) mit Imidacloprid wurde Hsp 70 induziert und war sowohl im Zytoplasma als auch im Zellkern zu finden, während Hsp 90 im Zytoplasma der meisten Zellen nachweisbar war. Die Hsp-Aktivität war bei Coumaphos behandelten Gruppen deutlicher als bei den Imidacloprid behandelten. Coumaphos führte außerdem zu höheren Zelltodraten als Imidacloprid, während nach Imidaclopridbehandlung mehr Nekroseschäden zu sehen waren. Bei den 7–12 Tage alten Arbeiterinnen lag die Zelltodrate nach 48 stündiger Imidacloprid-Behandlung bei 50 % und erfasste bei längerer Behandlung (72 Std.) nahezu alle Zellen. Die normalen Zelltodraten bei Kontrollen lagen bei 10 %. Wir schliessen daraus, dass beide Pestizide die Größe der Hypopharynxdrüsen negativ beeinflussen können und dass eine längere Exposition zum Zelltod führt. Unser Versuchsansatz erlaubt es auch, subletale Effekte auf bestimmte Organe erkennen zu können. Diese Nachweisverfahren können damit Hilfsmittel darstellen, um die zelluläre Antwort in Hypopharynxdrüsen nach Feldeinsätzen von Imidacloprid, bzw. von Coumaphos in Bienenvölkern zu erfassen.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Atkins E.L. (1998) Injury to honeybees by poisoning, in: Graham J.M. (Ed.), The hive and the honey bee, Dadant & Sons: Hamilton, Illinois, USA, pp. 1169–1171.

Babendreier D., Kalberer N.M., Romeis J., Fluri P., Mulligan E., Bigler F. (2005) Influence of Bttransgenic pollen, Bt-toxin and protease inhibitor (SBTI) ingestion on development of the hypopharyngeal glands in honeybees, Apidologie 36, 585–594.

Beckmann R.P., Lovett M., Welch W.J. (1992) Examining the function and regulation of hsp70 in cells subjected to metabolic stress, J. Cell Biol. 117, 1137–1150.

Beckmann R.P., Mizzen L.A., Welch W.J. (1990) Interaction of Hsp70 with newly synthesized proteins: implications for protein folding and assembly, Science 248, 850–854.

Bierkens J.G.E.A. (2000) Application and pitfalls of stress-proteins in biomonitoring, Toxicology 153, 61–72.

Bowen I.D., Mullarkey K., Morgan S.M. (1996) Programmed cell death in the salivary gland of the blow fly Calliphora vomitoria, Microsc. Res. Techniq. 34, 202–217.

Chiang H., Terlecky S.R., Plant C.P., Dice J.F. (1989) A role for a 70-Kilodalton Heat Shock protein in Lysosomal Degradation of Intracellular Proteins, Science 246, 382–385.

Clarke P.G.H. (1990) Developmental cell death; morphological diversity and multiple mechanisms, Anat. Embryol. 181, 195–206.

Crailsheim K. (1998) Trophallactic interactions in the adult honeybee (Apis mellifera L.), Apidologie 29, 97–112.

Crailsheim K., Stolberg E. (1989) Influence of diet, age and colony condition upon intestinal proteolytic activity and size of the hypopharyngeal glands in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.), J. Insect Physiol. 35, 595–602.

Crailsheim K., Hrassnigg N., Lorenz W., Lass A. (1993) Protein consumption and distribution in a honeybee colony (Apis mellifera carnica Pollm.), Apidologie 24, 509–511.

Cruz-Landim C. da, Hadek R. (1969) Ultrastructure of Apis mellifera hypopharyngeal glands, Proc. 6th Int. Congr. IUSSI, Bern.

Cruz-Landim C. da, Silva de Moraes R.L.M. (1977) Estruturas degenerativas nas glandulas hipofaringeas de operarias de Apis mellifera (Apidae), Rev. Brasil Biol. 37, 681–692.

Dade H.A. (1962) Anatomy and dissection of the honeybee, International Bee Research Association: Cardiff, UK.

Decourtye A., Armengaud C., Renou M., Devillers J., Cluzeau S., Gauthier M., Pham-Delegue M.-H. (2004) Imidacloprid impairs memory and brain metabolism in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.), Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 78, 83–92.

Deseyn J., Billen J. (2005) Age-dependent morphology und ultrastructure of the hypopharyngeal gland of Apis mellifera workers (Hymenoptera, Apidae), Apidologie 36, 49–57.

Feder M.E., Parsell D.A., Lindquist S.L. (1995) The stress response and stress proteins, in: Lemasters J.J., Oliver C. (Eds.), Cell Biology of Trauma, CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, pp. 177–191.

Garrido C., Gurbuxani S., Ravagnan L., Kroemer G. (2001) Heat shock proteins: endogenous modulators of apoptotic cell death, Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 286, 433–442.

Georgopoulos C., Welch W.J. (1993) Role of the major heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones, Ann. Rev. Cell. Biol. 9, 601–634.

Gregorc A., Bowen I.D. (1996) Scanning electron microscopy of the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) larvae midgut, Zb. Vet. Fak. Univ. Ljubljana 33, 261–269.

Gregorc A., Bowen I.D. (1997) Programmed cell death in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) larvae midgut, Cell Biol. Int. 21, 211–218.

Gregorc A., Bowen I.D. (1999) In situ localisation of heat shock and histone proteins in honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) larvae infected with Paenibacillus larvae, Cell Biol. Int. 23, 211–218.

Gregorc A., Bowen I.D. (2000) Histochemical characterisation of cell death in honeybee larvae midgut after treatment with Paenibacillus larvae, amitraz and oxytetracycline, Cell Biol. Int. 24, 319–324.

Gregorc A., Smodiš Škerl M.I. (2007) Toxicological and immunohistochemical testing of honeybees after oxalic acid and rotenone treatments, Apidologie 38, 296–305.

Gregorc A., Pogacnik A., Bowen I.D. (2004) Cell death in honeybee (Apis mellifera) larvae treated with oxalic or formic acid, Apidologie 35, 453–460.

Hendrick J.P., Hartl F.U. (1993) Molecular chaper-one functions of heat-shock proteins, Ann. Rev. Biochem. 62, 349–384.

Hrassnigg N., Crailsheim K. (1998) Adaptation of hypopharyngeal gland development to the brood status of honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies, J. Insect Physiol. 44, 929–939.

Huang Z-Y., Robinson G.E., Borst D.W. (1994) Physiological correlates of division of labour among similarly aged honeybees, J. Comp. Physiol. 174, 731–739.

Jakob U., Buchner J. (1994) Assisting spontaneity: the role of Hsp 90 and small Hsps as molecular chaperones, Trends Biochem. Sci. 19, 205–211.

Köhler H.R., Triebskorn R., Stocker W., Kloetzel P.M., Alberti G. (1992) The 70 kD heat shock protein (HSP 70) in soil invertebrates: a possible tool for monitoring environmental toxicants, Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 22, 334–338.

Lass A., Crailsheim K. (1996) Influence of age and caging upon protein metabolism, hypopharyngeal glands and trophallactic behaviour in the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.), Insect. Soc. 43, 347–358.

Levy R., Benchaib M., Cordonier H., Souchier C., Guerin J.F. (1998) Annexin V labelling and terminal transferase-mediated DNA end labelling (TUNEL) assay in human arrested embryos, Mol. Hum. Reprod. 4, 775–783.

Matylevitch N.P., Schuschereba S.T., Mata J.R., Gilligan G.R., Lawlor D.F., Goodwin C.W., Bowman P.D. (1998) Apoptosis and accidental cell death in cultured human keratinocytes after thermal injury, Am. J. Pathol. 153, 567–577.

Maulik N., Yoshida T., Das D.K. (1998) Oxidative stress developed during the reprefusion of ischemic myocardium induces apoptosis, Free Radical. Bio. Med. 24, 869–875.

Maurizio A. (1954) Pollenernährung und Lebensvorgänge bei der Honigbiene (Apis mellifera L.), Landwirtsch. Jahrb. Schweiz 62, 115–182.

Michener C.D. (1974). The social behaviour of the bees, Harvard University Press.

Papaefthimiou C., Pavlidou V., Gregorc A., Theophilidis G. (2002) The action of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid on the isolated heart of insect and amphibia, Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 11, 127–140.

Pelham H.R.B. (1986) Speculations on the functions of the major heat shock and glucose-regulated proteins, Cell 46, 959–961.

Pettis J.S., Collins A.M., Wilbanks R., Feldlaufer M.F. (2004) Effects of coumaphos on queen rearing in the honeybee, Apis mellifera, Apidologie 35, 605–610.

Rassow J., Voos W., Pfanner N. (1995) Partner proteins determine multiple functions of Hsp70, Trends Cell Biol. 5, 207–212.

Rosiak K.L. (2002) The effects of two polychlorinated biphenyl mixtures on honeybee (Apis mellifera) foraging behaviour and hypopharyngeal gland development. Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Sasagawa H., Sasaki M., Okada I. (1989) Hormonal control of the division of labour in adult honeybees (Apis mellifera L.): 1. Effect of methoprene on corpora allata and hypopharyngeal gland and its alpha-glucosidase activity, Appl. Ent. Zool. 24, 66–77.

Schmuck R., Nauen R., Ebbinghaus-Kintscher U. (2003) Effects of imidacloprid and common plant metabolites of imidacloprid in the honeybee: toxicological and biochemical considerations, Bull. Insect. 56, 27–34.

Schwartz L.M. (1991) The role of cell death genes during development, Bioessays 13, 389–395.

Sgonc R., Gruber J. (1998) Apoptosis detection: an overview, Exp. Gerontol. 33, 525–533.

Shi Y., Thomas J.O. (1992) The transport of proteins into the nucleus requires the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein or its cytosolic cognate, Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 2186–2192.

Silva de Moraes R.L.M., Bowen I.D. (2000) Modes of cell death in the hypopharyngeal gland of the honeybee (Apis mellifera L), Cell Biol. Int. 24, 737–743.

Silva de Moraes R.L.M., Brochetto-Braga M.R., Azavedo A. (1996) Electrophoretical studies of proteins of the hypopharyngeal glands and of the larval food of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides Lep. (Hym., Meliponinae), Insect. Soc. 43, 183–188.

Silva-Zacarin E.C.M., Gregorc A., Silva de Moraes R.L.M. (2006) In situ localisation of heat-shock proteins and cell death labelling in the salivary gland of acaricide-treated honeybee larvae, Apidologie 37, 507–516.

Snodgrass R.E. (1956) Anatomy of the Honey Bee, Comstock Publ. Assoc. Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca N.Y.

Suchail S., Guez D., Belzunces L.P. (2000) Characteristics of imidacloprid toxicity in two Apis mellifera subspecies, Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 19, 1901–1905.

Suwannapong G., Seabualuang P., Wongsiri S. (2007) A histochemical study of the hypopharyngeal glands of the dwarf honeybees Apis andreniformis and Apis florea, J. Apicult. Res. 46, 260–263.

White E. (1996) Life death and the pursuit of apoptosis, Genes and Development 10, 1.

Winston (1987) The biology of the honeybee, Harvard University Press: Cambridge MA, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Manuscript editor: Klaus Hartfelder

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Škerl, M.I.S., Gregorc, A. Heat shock proteins and cell death in situ localisation in hypopharyngeal glands of honeybee (Apis mellifera carnica) workers after imidacloprid or coumaphos treatment. Apidologie 41, 73–86 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2009051

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2009051