Key Points

-

Highlights the need to train residential home carers to provide oral hygiene.

-

Describes a pilot training scheme to enable them to carry out oral hygiene provision.

-

Reports the evaluation of this training scheme.

Abstract

Objective This pilot study aimed to produce and evaluate training resources and training in oral health care, including oral hygiene, for carers in care homes in Surrey and Medway.

Methods During two training days, for carers from these homes, short, interactive presentations were given on a range of topics relevant to oral health care and oral hygiene of older people, followed by practical training. Prior to any training all attendees completed a 39 question questionnaire to establish their baseline knowledge of oral health and hygiene. At the end of the training day they completed an evaluation form. Fourteen weeks later, they were visited at their place of work and completed the same questionnaire again. Differences in responses between baseline and after 14 weeks were statistically tested using the chi-squared test.

Results Sixty-six carers attended the training sessions and 44 were followed up 14 weeks later. The results showed an improvement in carer knowledge at follow up. The majority of carers (36/44) spoke English as their first language. They had a mean age of 41 years, 37 were female and 7 male. They had worked as carers for a mean of 10.9 years (range 4 months–34 years). Over 90% stated that the training day fully met or exceeded their requirements and expectations.

Conclusions The results indicated improvements in carer knowledge. However, the carers were atypical of carers in general, as they were self-selected and well-motivated. Nevertheless the content of the training day and the questionnaire should inform future work in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In common with most developed countries there are growing numbers of people aged over 65 years (older people) in the population of the UK.1 Although many live either with their families or alone, in the UK some 400,000 people now live in residential (care and nursing) homes, the majority of whom are older people.2 It appears that the percentage who do so may be higher in the South of England, especially in seaside towns.2 The most recent Adult Dental Health Survey indicated that more than half of over 65-year-olds have retained some natural teeth and fewer are edentulous than in the past 40 years.3

However, due to physical limitations, which have been the consequence of conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and stroke, many need help with their oral hygiene.4 There are also increasing numbers of older people with dementia5 who also need such daily help. Many older people are taking medication which has the side effect of causing xerostomia. Those living in care homes, therefore, have high need for oral care6,7,8 and have been shown to have higher healthcare and oral healthcare needs than those living in their own homes.9,10 Unfortunately, a number of studies have found that the oral care of those living in care homes is often neglected.11,12,13 This can have a negative influence on general health14,15 for example increasing the risk of community acquired pneumonia15,16 and also affecting quality of life.17 Furthermore, the importance of good oral health and daily oral hygiene is often poorly understood by carers.12

To compound the problem, carers are often not trained to provide oral health care7,13,19,20 and may dislike doing so.21 Carers in residential homes are also prone to high turnover, with one study suggesting that 60% leave within two years of taking up employment in a care home.22

In an effort to tackle these problems, a new NHS policy for institutionalised older people has been introduced.23 Local authorities now have a responsibility for the oral health of over 65-year-olds living in homes (Health and Social Care Act 2012). In Surrey and Sussex the 'Caring for Carers' specification links this responsibility to clauses 114 and 115 of GDS/PDS contract. There are also guidelines on the provision of oral hygiene in residential homes oral hygiene, both in the UK23 and in some European countries.11 The Care Quality Commission (CQC), the organisation responsible for monitoring care standards in healthcare in England, has also issued overall guidelines for care in residential homes.24

There have been several previous schemes to train carers in residential homes to provide oral hygiene25,26,27 and many others are being developed in different parts of the UK. Furthermore, it has been shown that an oral hygiene education programme for caregivers led to an improvement in the oral hygiene of elderly care home residents.28

However, it is not just the day-to-day carers who need training to help improve the oral care of older people living in residential homes, or who are housebound in their own homes. Their relatives should be made aware as should all dental team members and other healthcare workers who provide care for older people.

To address this need in Kent, Surrey and Sussex, an ambitious two year programme is currently taking place. This paper reports the initial assessment of training resources and training outcomes in a scheme to train care home carers in Surrey and Medway, which was performed as a preliminary to the main programme.

Objective

The aim of this study was to produce and evaluate training resources and training in oral healthcare, including oral hygiene, for carers in care homes in Surrey and Medway.

Methods

The owners of private care homes in and around Guildford (Surrey) and Medway (North Kent) and the local authorities who owned other such homes were contacted, the aims of the pilot scheme where explained to them and they were invited to send carers to one of two training days held in March 2014. One was held in Guildford and one in Chatham. The training days took place in the education centre of the Royal Surrey County Hospital (Guildford) and at the University of Kent (Medway Maritime Campus, Chatham).

Prior to the training days, the protocol for the pilot was sent to the NHS Research Management and Governance Officer for Kent and Medway for independent ethics review. He advised that as the questionnaire was in effect a survey of NHS and other staff and its completion was voluntary, as was participation in the pilot, ethics approval was not required. The owners of the care homes where the participants worked approved the participation of their staff (carers) in the study.

On arrival, after a brief introduction to the aims and programme for the day, before any other presentations or training, the carers were asked to complete a 39-question baseline questionnaire (Fig. 1 in the supplementary information available online). They were also asked to complete the same questionnaire during follow up visits to the care homes where they worked to assess whether or not here had been an improvement in the carers' knowledge of oral health or any change in their attitudes.

Completion of the questionnaire was voluntary and anonymous, in that carers did not record their names or place of work on the questionnaire. The formal training then commenced. Prior to lunch, a series of short presentations were given on the topics of:

-

Meeting CQC essential standards outcomes, which included details on how CQC outcomes related to oral care in the care home setting

-

'Mouth Care - an essential part of general health', which included images of dental caries, gingivitis and periodontitis, the causes of these diseases and their prevention through appropriate diet and good oral hygiene

-

'What to look for in the mouth'- which covered diseases and conditions of the oral mucosa, with an emphasis on xerostomia, oral cancer, denture stomatitis and oral ulceration

-

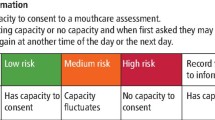

Oral health risk assessment forms and mouth care plans for residents, which included the various aspects of the forms and the outcomes from completed assessments

-

'Mouth care products', which included hands on discussion regarding the various oral care products available, and samples for the carers to use.

After lunch the carers split into three small groups and rotated around three activities. The first was practical instruction in the provision of oral hygiene to older people. This included demonstrations of tooth-brushing (with manual and power toothbrushes), denture identification labelling, cleaning and storage, treatment of dry mouths, use of tongue scrapers and mouthwashes. Under supervision, they then practiced giving oral hygiene to each other.

The second involved viewing a wide range of oral hygiene aids, designed for older people and discussing when they should be used and watching a DVD created by the British Society of Gerodontology on delivering oral care in care home settings.

The third was to view a scenario performed by actors in which carers provided oral hygiene for an older person with advanced dementia and to discuss it with the trainer and actors.

The three small groups then merged for a discussion and questions and an explanation of the follow-up actions and the completion of evaluation forms of the day by the participants.

The follow-up consisted of visits by two of the presenters from the training day (HL, MW) and an experienced GDP in this field (JS), at least 14 weeks later, to the residential homes, where the carers worked. At these visits the same questionnaire (Fig. 1 in the supplementary information available online) was distributed to be completed for a second time to assess whether or not here had been an improvement in the carers' knowledge of oral health or any change in their attitudes.

The visitors produced reports of their visits. Answers to the questionnaire at baseline and follow-up were then analysed. The null hypothesis that there was no difference in carers' responses at baseline and 14 weeks was tested at the 0.05 level using 2x2 cross tabulated chi-squared test (1df) or, where numbers were low, using Fisher's exact probability test.

Although the questionnaires were completed anonymously, and it was not possible to identify individual carers by name or where they worked, it was possible to identify which carer had completed both forms. This was by relating the answers of individuals to questions on age, gender, if English was their first language and length of work as a carer.

Results

Sixty six carers from 21 homes attended the two training days, of whom 25 went to Guildford and 41 to Chatham. Of these 44 (17 who had attended at Guildford and 27 at Chatham) were available during follow up visits 14 weeks later and completed the questionnaire for a second time. The 22 carers who did not complete the questionnaire at the 14 week visit were either not on duty at the time of the visit or on holiday or, in one case, had left employment at the residential home concerned. The responses to the other questions now follow in the order that the questions appeared in the questionnaire.

Demographic profile of carers at baseline

The age range of the carers was from 20 to 64 years (average age 41.5 years). Thirty-seven were female and seven male. They had worked as carers for between four months and 34 years with an average 10.9 years. They had worked in their current residential home from between four months and 25 years (average 5.4 years). Thirty six spoke English as their first language and eight (18%) as their second or third language. Sixteen reported that they had received previous training in providing oral hygiene for residents, 26 that they had not received such training and two did not answer this question. The mean age of the 22 carers who did not complete the questionnaire again 14 weeks after baseline was 44 years, similar (41.5 years) to that of those who completed the questionnaire for the second time and they had worked as carers for a mean of 8.5 years in comparison to the average of 10.9 years for the second time completers.

Results comparing answers at baseline and 14 weeks later that are presented in this results section are therefore based on the 44 carers who completed the questionnaire on both occasions. In this results section and in the tables P values are given only when there was a statistically significant difference between numbers at baseline and after 14 weeks.

Cleaning mouths and dentures

Both at baseline and after 14 weeks, 43 carers responded that they were happy to clean residents' mouths, one carer did not respond to this question. On both occasions, all 44 responded that they were happy to clean dentures. One carer stated that he/she did not like the smell of mouths and one that he/she had once been bitten when cleaning a resident's mouth. As far as cleaning frequency for dentate patients was concerned, at baseline 42 carers stated twice daily and two did not answer. After 14 weeks, all 44 carers stated twice daily. Responses to the question 'When to clean dentures' - the number of carers responding twice per day fell from 18 at baseline to 14 after 14 weeks and last thing at night rose from 25 at baseline to 30 after 14 weeks (Table 1). In response to the question - when do you clean residents' mouths - both at baseline and after 14 weeks, 39 carers answered twice per day. The only statistically significant change was that 38 carers reported that they were confident to clean the mouths residents with dementia after 14 weeks as opposed to 30 at baseline P <0.05 (Table 2).

Importance for health and dry mouth

In response to question 4 - 'Importance for health' - both at baseline and after 14 weeks, more than 40 carers answered tooth decay, pain and bleeding gums on both occasions. After 14 weeks, there were slight increases in the numbers answering smelly mouth, may loosen teeth, limits enjoyment and CQC says so. As far as causes of dry mouth (question 7) were concerned, the two factors which were recognised more frequently after 14 weeks were ageing, 28 of the responses at baseline and 38 after 14 weeks (P < 0.05), and Sjögren's which rose from five of the responses to 18 responses (P < 0.002.) (Table 3). Reponses to questions on the care of dry mouths suggested an increased awareness after 14 weeks of the roles of saliva replacements (27 responses to 37 after 14 weeks (P <0.05), sugar-free mouthwashes (21 to 28) twice daily oral hygiene (24 to 31) and twice daily denture cleaning (17 to 24) (Table 4).

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)

At baseline, 15 carers reported that they PEG fed residents. This number rose to 17 after 14 weeks. At baseline, 15 stated that they cleaned the mouths of PEG fed residents twice per day. After 14 weeks, 16 claimed that they cleaned PEG fed residents' mouths twice per day.

Pneumonia and oral cancer

At baseline, only 11 of carers stated that they knew that pneumonia could arise from oral microbes, 30 that they did not know this and three did not answer. After 14 weeks, 34 of the carers stated that they were aware of this risk, which was a significant change (P < 0.01), nine that they did not know and one did not answer (Table 5). At baseline, 13 of the carers stated that they knew how many residents in the home(s), where they worked, had died from pneumonia in the last year. After 14 weeks, only 10 stated that they knew.

Encouragingly, both at baseline and after 14 weeks, no carer stated that they would do nothing if a resident had had a painless ulcer for 14 days or longer. At baseline, 30 said that they would ask a dentist to look at the mouth of such a patient. After 14 weeks, all 44 said that they would ask a dentist to look at such a patient (P <0.05) (Table 5). Both at baseline 33 and after 14 weeks, 35 of the carers stated that such a lesion should be checked because it might be oral cancer.

Tooth decay and bleeding gums

There were relatively few changes between baseline and 14 weeks with regard to knowledge of factors causing tooth decay. Somewhat surprisingly, during this period, the numbers who answered that 'bacteria in the mouth' fell from 40 to 34 and 'sugars were causes' from 34 to 29 (Table 6). Although brushing twice per day with a fluoride toothpaste, 40 at baseline and 41 after 14 weeks was seen as a most important factor to prevent tooth decay, only 14 of the carers on both occasions considered that limiting sugar consumption to mealtimes was important (Table 7).

More encouragingly, at both baseline and after 14 weeks, over 40 carers recognised that build-up of plaque and poor plaque removal were factors that led to bleeding gums and 43 (98%) (at baseline) and 39 (after 14 weeks) that interdental and sulcular cleaning were important to prevent bleeding gums.

Over this period the number who recognised smoking as a detrimental factor for gums rose from 32 to 40 (P < 0.05)(Table 5).

Key time to brush

At baseline, 40 carers answered that before going to bed to sleep was the key time to brush teeth and gums. After 14 weeks the number increased to 43and one 'answered don't know'.

Referral from care home to a dentist

At baseline, 27 carers reported that this happened from the home where they worked, five that it did not and 12 did not know. After 14 weeks, these numbers changed to 24 for 'Yes', 9 for 'No' and 11 for 'did not know'.

Availability of oral hygiene materials

Both at baseline and after 14 weeks, 42 of the carers reported that oral hygiene materials (toothbrushes, etc.) were readily available to residents. Only one carer reported that they were not available and one did not know. The one, who did not know, did not answer question 24, which was to list unavailable materials.

Confidence to clean mouths of residents with dementia, give advice and to look for abnormalities

At baseline, 30 of the carers reported that they were confident to clean the mouths of uncooperative and/or residents with dementia, nine that they were not confident and five did not know. After 14 weeks the number who reported that they were confident rose to 38 (P < 0.05), three that they were still not confident and three did not know. As far as giving oral hygiene advice to residents was concerned, at baseline, 41 reported that they were confident, two that they were not confident and one did not know. After 14 weeks, 43 said they were confident to give advice and one that he/she was not. A very high number of carers also reported confidence in looking for abnormalities: Forty-one answering yes to this question at baseline and all 44 after 14 weeks.

Carers personal oral care and habits

Twenty three reported that they visited a dentist at least once per year, 11 only when they perceived a need, four when their dentist told them to, three only when in pain and three did not answer this question. Thirty-two reported that they used a manual toothbrush and 12 an electric (powered) toothbrush. Thirty-three said they used other oral hygiene devices in addition to a toothbrush and 11 that they did not. At baseline, 16 carers reported that they had no fear of visiting a dentist and six that they just had fear for specific treatments such as fillings or extractions. These numbers rose to 17 and 7 after 14 weeks. Also at baseline, eight and, after 14 weeks, 11 said they were always very nervous. A small number, seven at baseline and three after 14 weeks, said that they were not afraid of treatment but were afraid of possible costs of a dental visit. Question 38 was withdrawn as it was answered by very few carers. The final question asked carers to rate their fear of a dental visit on a scale of zero (no fear) to ten (very nervous). At baseline, 17 answered zero and four answered ten. After 14 weeks, these became 13 and seven (Table 8). However, five of the 22 carers who did not complete the questionnaire again after 14 weeks answered ten (very nervous) at baseline.

Discussion

The aim of this pilot was to produce and evaluate training resources and training in oral healthcare, including oral hygiene, for carers in care homes in Surrey and Medway. As such it should be considered as a 'service' evaluation rather than a structured trial. The carers who attended the two training sessions must be considered to be a convenience sample and, as will be discussed later on in this section, were probably not representative of all carers in Surrey and Medway It was also unfortunate that 22 (33) of the carers out of the original 66 were unavailable to complete the questionnaire after 14 weeks. However, given the pressures and constraints of day to day work in a care home, it was perhaps unsurprising, and was a better follow up rate than that in a recent training programme in Scotland.25

Since this pilot training programme took place, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has produced guidance on approaches for adult nursing and residential care homes on promoting oral health, preventing dental health problems and ensuring access to dental treatment. Prior to the production of the guidance, after a literature review, the NICE review team produced evidence statements on a number of issues. From the 23 studies reviewed (only three of which took place in the UK), the effectiveness of carer education or protocol/guideline introduction in improving the oral health of residents was found to produce inconsistent results, with regard to the overall effect. The same 23 studies indicated that the hours of carer education did not appear to influence the outcome. However, there was moderate evidence, from eight studies (none of which took place in the UK), that a protocol/guideline supported by care education was more likely to be effective than education alone.29 This information could have influenced the design of this pilot.

The level of oral health knowledge of the carers who attended the two training sessions was at a higher level than the organisers had anticipated. They had all volunteered to attend and the owners of the homes where they worked were motivated to send them to the course. The answers they gave to the demographic questions on age, length of service as carers, time in present employment and English as a first language, suggested that most had several years of experience as carers and had worked in their present post for on average over five years. This is in contrast with the finding of the National Care Forum survey in 2008 which found that 60% of carers left their job within two years of taking it up.22 In short, as previously mentioned they may not have been representative of the generality of carers in residential homes.

The completion of the questionnaire at baseline, before the delivery of any training, should have ensured that the carers' answers reflected their baseline knowledge. It was encouraging to see that, in most areas, answers to the same questions 14 weeks after training, suggested that the oral health knowledge of the carers had improved since baseline, particularly as far as understanding that an unclean mouth was a risk factor for pneumonia16,17 and the need to refer any resident with an oral ulcer for more than 14 days to a dentist. The one key area in which there was no improvement between baseline and after 14 weeks was the recognition of the need to limit sugar containing food and drinks to mealtimes, with only 14 (31.8%) carers giving the answer that this was important. The recent WHO guidance, on the need to reduce the daily intake of dietary sugar,30 was published after the two training sessions. It may have subsequently raised the awareness of carers to the problems arising from sugar intake. However, be this as it may, in the group of carers who took part in this study, there was a need for training on nutrition and, in particular, sugar intake.

Fourteen weeks can be viewed as sufficient time to forget knowledge and the carers who attended the training days did not take notes. Nevertheless, they were very enthusiastic and the format of short oral presentations in the morning, which carefully avoided using complex language, involved interaction with the audience and practical training in small groups in the afternoon worked very well. At the end of each training day, the carers were asked to complete written forms to evaluate the training they had received. Over 90% stated that the training day fully met or exceeded their requirements and expectations indicating that the carers had enjoyed the day very much, had viewed it as a very positive experience and felt motivated to improve the oral healthcare of the residents in the homes where they worked.

Conclusions

The results from the two questionnaires and the comments of the carers who participated in the training days suggest that the format of the training days, their content and the interactive and practical nature of the training, improved the oral health knowledge of this group of carers and that 14 weeks after the training they had maintained the knowledge and enthusiasm. As such it has been used in the main study in Kent, Surrey and Sussex that is currently running and could be of use to any group training carers in the provision of oral hygiene and with the aim to raise their awareness of the importance of oral healthcare for older people.

References

Office for National Statistics. Ageing in the UK datasets. Available online at http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/mortality-ageing/ageing-in-the-uk-datasets/index.html (accessed June 2016).

Care Quality Commission. State of Care 2014/15. Available online at www.cqc.org.uk/content/state-care-201415 accessed on 26 June 2016.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 - Summary Report and Thematic Series [NS]. Available at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/pubs/dentalsurveyfullreport09 (accessed June 2016).

Frenkel H, Harvey I, Newcombe R G . Oral health care among nursing home residents in Avon. Gerodont 2000; 17: 33–38.

Alzheimers Society. Dementia 2014 report statistics. Available at www.alzheimers.org.uk/statistics (accessed June 2016).

Fiske J, Lloyd H A . Dental needs of residents and carers in elderly peoples' homes and carers' attitudes to oral health. Eur J Prosthodont Rest Dent 1992; 1: 91–95.

Sweeney M.P, Williams C, Kennedy C, MacPherson L M.D, Turner S, Bagg J . Oral Health Care status of elderly care home residents in Glasgow. Comm Dent Health 2007; 24: 37–42.

Karki A J, Monaghan N, Morgan M . Oral health status of older people living in care homes in Wales. Br Dent J. 2015; 219: 331–334.

Müller F, Naharro M, Carlson G E . What are the prevalence and incidence of tooth loss in the adult and elderly population in Europe. Clin Oral Implants Res 2007; 18 (Suppl 3): 2–14.

Johnson I G, Morgan M Z, Monaghan M P, Karki A J . Does dental disease presence equate to treatment need among care home residents? J Dent 2014; 42: 929–937.

Vanobbergen J.N, DeVisschere L M. Factors contributing to the variation in oral hygiene community practices and facilities in long-term care institutions for the elderly. Comm Dent Health 2005; 4: 260–265.

Reiss S.C, Marcelo V C., da Silva E.T, Leies C R . Oral health of the institutionalise elderly: a qualitative study of health caregivers perceptions in Brazil. Gerodont 2011; 1: 69–75.

Monaghan N, Morgan M Z, Oral health policy and access to dentistry in care homes. J Disab Oral Hlth 2010; 11: 61–68.

Fiske J, Griffiths J, Jamieson R, Manger D. Guidelines for oral health care for long-stay patients and residents. Gerodont 2000; 17: 55–64.

Sheiham A, Steele J, Marcenes W, Lowe C, Finch S, Bates C et al. The relationship among dental status, nutrient intake and nutritional status in older people. J Dent Res 2001; 80: 408–413.

Sarin J, Balasubramaniam R, Corcoran A.M, Laudenbach J.M, Stoopler E T . Reducing the risk of aspiration pneumonia among elderly patients in long-term care facilities through oral health interventions. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008; 2: 128–135.

Yoneyama T, Yoshida M, Ohrui T et al. Oral Care Working Group; oral care and pneumonia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 430–433.

Walls A W., Steele J C . The relationship between oral health and nutrition in older people. Mech Age Dev 2004; 12: 853–857.

Rak O.S, Warren K . An assessment of the level of dental and mouthrinse knowledge among nurses working with elderly patients. Comm Dent Health 1990; 7: 295–300.

Adams R . Qualified nurses lack adequate knowledge related to oral health, resulting in inadequate oral care of patients on medical wards. J Adv Nurs 1996; 24: 552–560.

Wardh I, Andersson L, Sörensen S . Staff attitudes to oral health: a comparative study of registered nurses, nursing assistants and home care workers. Gerodont 1997; 14: 28–32.

Social Care Institute for Excellence. National Care Forum- Personnel Statistics 2008: Survey of NCF Member Organisations. Available at http://www.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk/search?q=publisher_name%3a%22national+care+forum%22&f_publication_year=2008&page=1 (accessed June 2016).

Department of Health. Patient care and compassionate care in the NHS – Fundamental standards for health and social care providers. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/fundamental-standards-for-health-and-social-care-providers (accessed June 2016).

Care Quality Commission. What standards can you expect from a good care home. Updated 2016 Available at https://uk-mg42.mail.yahoo.com/neo/launch?.partner=bt-1&.rand=4gs9urlpk2j1g (accessed June 2016).

Duane B.G, Kirk D, Forbes G.M, Ball G . Inspiring and recognizing good oral health practice within care homes. J Disab Oral Hlth 2011: 12: 3–9.

Nicol R., Sweeney P.M, McHugh S, Bagg J . Effectiveness of health care worker training on the oral health of elderly residents of nursing homes. Comm Dent Oral Epidem 2005; 2: 115–124.

Frenkel H.F, Harvey I, Needs K M . Oral health care education and its effect on caregivers' knowledge and attitudes: a randomised controlled trial. Comm Dent Oral Epidem 2002; 30: 93–100.

Portella F.F, Rocha A W., Haddad D.C . Oral hygiene caregivers' educational programme improves oral health conditions in institutionalised independent and functional elderly. Gerodont 2015; 32: 28–34.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Approaches for adult nursing and residential care homes on promoting oral health, preventing dental health problems and ensuring access to dental treatment. Review of evidence 2015. Available online https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/GID-PHG62/documents/evidence-review (accessed April 2016).

World Health Organization. Guideline – Sugars intake for adults and children. 2015. Available online at http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/sugars_intake/en/ (accessed September 2015).

Scott S E, Khwaja M, Low E L, Weinman J, Grunfeld E A . A randomised controlled trial of a pilot intervention to encourage early presentation of oral cancer in high risk groups. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 88: 241–248.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the owners of the care homes, whose employees attended the training days, and the carers for taking part in this pilot. They also thank Health Education England for funding the project

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eaton, K., Lloyd, H., Wheeler, M. et al. Looking after the mouth – Evaluation of a pilot for a new approach to training care home carers in Kent, Surrey and Sussex. Br Dent J 221, 31–36 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.497

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.497