Key Points

-

Presents an overview on the use and pharmacology of aspirin and clopidogrel.

-

Highlights the difficulties in managing patients on dual antiplatelet therapy.

-

Reviews the current literature on dual antiplatelet therapy during oral surgical treatments.

-

Outlines a protocol for the management of patients on dual antiplatelet therapy.

Abstract

Background Haemostasis is crucial for the success of oral surgical treatment as bleeding problems can cause complications both pre- and post-operatively. Patients on antiplatelet drugs present a challenge due to their increased risk of bleeding.

Aims To identify a protocol for the management of oral surgery patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel).

Methods A literature review was conducted in January 2016 of free-text and MESH searches (keywords: aspirin, clopidogrel and dental extractions) in the Cochrane Library, PubMed and CINAHL. Trial registers, professional bodies for guidelines and OpenGrey for unpublished literature were also searched. Studies were selected for appraisal after limits were applied (adult, human and English only studies) and inclusion/exclusion criteria imposed.

Results Eight studies were identified for critical appraisal using the CASP tools. These were a combination of retrospective, prospective, cohort and case control studies. Napenas et al. and Park et al. found no statistically significant risk of postoperative bleeding complications in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy. Girotra et al., Lillis et al., Omar et al. and Olmos-Carrasco et al., however, found statistically significant risk of postoperative bleeding in this group of patients, all of which can be controlled with local measures.

Conclusion Patients on dual antiplatelet therapy – although at an increased risk of postoperative bleeding complications - can be managed safely with local haemostatic measures and without the need to discontinue antiplatelet therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Greek physicians Galen and Hippocrates first identified the use of salicylate containing plants as an antipyretic over 2000 years ago. However, it was not until the late nineteenth century that acetylsalicylic acid (or aspirin) was discovered and introduced as both an analgesic and antipyretic for medicinal purposes (Fig. 1).1 The antiplatelet effects were not revealed for a further 70 years, when aspirin was repurposed for the use in antiplatelet therapy.

Aspirin inhibits the metabolism of arachadonic acid by irreversibly inhibiting cycloxygenase enzymes, preventing the production of prostaglandins. By inhibiting cycloxygenase 2 (COX2), aspirin prevents the production of prostaglandins responsible for mediating pain and inflammation, therefore, acting as an anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and analgesic medicine.2 However, due to its non-specific mechanism, aspirin also inhibits cycloxygenase1 (COX1) which produces physiologically important prostaglandins responsible for platelet aggregation, protective function of the stomach lining and maintain kidney function.3

By inhibiting COX1, aspirin irreversibly blocks the formation of thromboxane A2 in platelets (Fig. 2)4, producing an inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation during the lifetime of the affected platelet (7–10 days).

Mechanism of action of aspirin and clopidogrel on platelets4

Low dose aspirin (75 mg daily) is indicated in patients for reducing the risk of myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke, especially in those who have undergone coronary stenting.5 It has been shown to prevent vascular events and even death in patients with peripheral vascular disease.6,7

Careful patient selection is important before considering prescribing aspirin, and should be avoided in children under 12, for patients with previous or active peptic ulceration or known bleeding disorders, and asthma.8

Clopidogrel (Plavix) is an antiplatelet medication used in patients following myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke and ischaemic vascular disease. It becomes an active metabolite in the liver after being activated by cytochrome P450 enzymes, and works by preventing adenosine diphosphate (ADP) from binding to its receptor (P2Y12) found on the surface of platelets (Fig. 2).4,9 This irreversibly inhibits platelet aggregation and cross linking of platelets by fibrin. The half-life is approximately eight hours at an optimal daily dose of 75 mg. Side effects of this treatment are similar to aspirin, and care must be taken in prescribing for patients with liver disease and increased clotting problems.

Prasugrel is another ADP receptor antiplatelet medication which is specified in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes in the NICE guidelines.10 Patients with acute coronary syndromes are usually treated with dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel), but in some instances there are variable degrees of responsiveness resulting in inadequate platelet inhibition, leading to the need to introduce a more potent and reliable drug such as Prasugrel.11 Prasugrel has a similar mechanism of action to clopidogrel, and works by inhibiting binding of ADP to receptors found on platelets, thus inhibiting platelet aggregation. Studies comparing post-extraction bleeding between patients taking prasugrel and clopidogrel show that bleeding times in patients taking prasugrel were significantly higher (on average 10 minutes longer) when compared to the group taking clopidogrel.12

Other ADP receptor inhibitors include ticlopidine, cangrelor, elinogrel and ticagrelor, although the clinical use and mechanism of action of such drugs are beyond the scope of this report. However, it is important that clinicians are aware of the uses and complications that can arise with such medications, by referring to the British National Formulary8 before commencing any form of treatment.

Current NICE Guidelines advise the use of dual antiplatelet therapy in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome and following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), such as stenting.13 This dual therapy has been shown to significantly prevent the occurrence of thrombotic event following PCI.6 The regime for most patients following PCI is 100 mg lifelong daily aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel for some months dependent on the type of stent used, metal or drug eluting, or endothelial progenitor cell capture stent,12 for 1–6 months, 9–12 months and as low as six weeks respectively.

Single antiplatelet therapy of aspirin alone is considered following a myocardial infarction, with clopidogrel used as a single antiplatelet therapy following an ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, peripheral arterial disease and multivascular disease.

Due to the mechanisms of dual antiplatelet therapy, there is an increase in the risk of bleeding complications both during and post dental surgery. The management of these patients present a challenge as the oral surgeon must weigh up the risk of bleeding versus the risk of thrombotic event should the antiplatelet regime be altered or discontinued.

Literature on patients on a single antiplatelet therapy (aspirin only) generally demonstrates that despite an increase in bleeding time, there are no current recommendations to stop aspirin before dental treatment.14,15 However, there is no known protocol for the management of patients undergoing dental extractions who are on dual antiplatelet therapy (both aspirin and clopidogrel).

The current management of these patients is clinician dependent, with differing surgeons providing different pre-operative advice regarding cessation of antiplatelet drugs. This can provide a number of difficulties:

-

Confusion among patients regarding preoperative preparation

-

Inconsistencies among operating staff

-

Attendance at hospital accident and emergency departments with postoperative haemorrhage

-

Delays in treatment as clinicians attempt to contact physicians regards drug management.

The aim of this research question is to clarify, with the aid of evidence-based literature, current protocols for the management of patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy.

Method

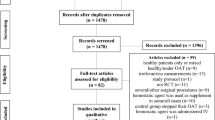

A literature review was conducted in January 2016 of free-text and MESH searches with the keywords: aspirin, clopidogrel and dental extractions, in the Cochrane Library, PubMed and CINAHL. Trial registers, professional bodies for guidelines and OpenGrey for unpublished literature were also searched. Singular and plural forms of words, synonyms, acronyms, different spellings, brand and generic names, truncation, and lay and medical terminology were all used in the PICO analysis (Table I). Boolean operators 'OR', 'AND' and 'NOT' were all applied. Studies were selected for appraisal after limits applied (adult, human and English only studies and inclusion/exclusion criteria imposed) (Table 2 and 3).

Results

A review of the literature has identified eight studies and a Cochrane protocol which considering the effects of dual antiplatelet therapy on the incidence of postoperative bleeding, and whether this effect merits discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy.

To date, there has been no Cochrane systematic review to summarise the effects of various interventions available to manage different types of post-operative bleeding. Sumanth et al.16 have introduced a protocol of interventions of managing post-extraction bleeding, which aims to collect and later provide evidence to guide clinical dental practice in the management of post-operative bleeding.

Girotra et al.17 report on their prospective randomised study of 139 patients on dual antiplatelet therapy versus 575 healthy individuals in the control group, who underwent a range of minor oral surgical procedures. They discovered statistically significant risk of bleeding with an odds ratio of 3.21 (95% confidence interval) in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy versus the control group. There was a greater need for haemostatic measures in these patients (P = 0.035), and this allowed control of bleeding complications.

Lillis et al.18 report on their prospective study of 33 patients on dual antiplatelet therapy versus a control group of 532 healthy individuals. All were subjected to dental extractions. There was again statistically significant (P <0.001) risk of bleeding post-operatively in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy. This risk was further increased by the presence of local inflammatory factors such as periodontal disease or pericoronitis.

Napenas et al.19 report on their retrospective study of 26 patients on dual antiplatelet therapy. There was no control group. All patients underwent 'invasive dental treatment' (oral surgery or periodontal). This report shows no readmission to accident and emergency with post-operative bleeding complications.

Park et al.20 report on their prospective study involving 59 patients on dual antiplatelet therapy and 100 matched patients in the control group. All underwent dental extractions. This report found no increased risk of bleeding in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy.

Gröbe et al.21 perform a retrospective single centre study on 60 patients on dual antiplatelet therapy versus a control group of 281 patients who underwent 'oral osteotomy' (bone invasion) procedures due to the higher risk of bleeding than simple dental extractions. They showed that 3.3% of patients on dual antiplatelet therapy presented with post-operative haemorrhage that was controlled with local measures, in comparison to 0.7% in the control group. However, due to the limited sample size, the incidence of post-operative bleeding was not significant between patient groups (P >0.45).

An observational, multicentre, prospective cohort study of 160 adult patients by Olmos-Carrasco et al.22 showed that 10% of patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) had intraoperative haemorrhage lasting more than 30 minutes following dental extractions. The presence of inflammation and three-rooted dental extractions increased the risk of post-operative bleeding by factors 10 and 7.3 respectively.

Post-operative bleeding in 129 patients taking different forms of dual antiplatelet therapies (100mg aspirin once daily in all patients, 63 patients on 75mg clopidogrel once/twice daily : 66 patients 10mg prasugrel once daily) was compared by Dezsi et al.12 The study also considered the use of local anaesthesia and associated co-morbidites (hypertension, diabetes mellitus and smoking status). These were found to be statistically insignificant, with no effect of existing co-morbidities or local anaesthesia with adrenaline on haemostasis.

Post-operative bleeding was 10 minutes longer in patients taking prasugrel (P <0.05) than those taking clopidogrel. The study concludes the need for suturing and gauze packs to control haemostasis, without the need to discontinue dual antiplatelet therapy.

A retrospective study on 71 patients by Omar et al.24 found a significant correlation between the number of teeth extracted and estimated blood loss in the patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (P = 0.012) when compared to those patients who were not taking antiplatelets. However, again the sample size was small and the evidence limited.

Discussion

Despite the limited evidence, lack of robust clinical data and inconsistencies in the results of the studies considered, the literature review has highlighted that patients on dual antiplatelet therapy can be managed appropriately with local haemostatic measures. Discontinuation of antiplatelet drugs should only be considered in conjunction with the prescribing physician.

All papers conclude that the management of these patients should be:

-

Not to discontinue any antiplatelet medications due to the risk of thrombotic event which outweighs the rick of post-operative haemorrhagic complications

-

There is some evidence to suggest that dual antiplatelet therapy can dispose patients to a greater risk of bleeding following dental extractions

-

Consider local and surgical factors (such as surgical complexity and inflammation of local soft tissues)

-

Provide verbal and written postoperative instruction, such as pressure pack over the surgical site, avoidance of physical exertion post-operatively and chewing on the opposing side of the surgical site

-

Application of local haemostatic measures (such as sutures and oxidised cellulose polymer, for example, Surgicel).

Larger and better designed studies are needed as existing studies are flawed for the following reasons:

-

Small populations studied

-

Inconsistencies in the literature about type of treatment provided, with ill defined parameters for quantifying haemorrhage

-

No statistical analysis of identified confounding factors.

Recommendations for practice

Based on the findings of the articles appraised, Grade D recommendations can be made (directly from level iv evidence and extrapolated from level iii evidence):

-

Appointments for extractions to be made in the morning and early in the week

-

Intraoperative bleeding can be managed with local haemostatic measures in this group of patients, such as oxidised cellulose, sutures, gauze pressure packs, acrylic splints and even tranexamic acid intra- and postoperatively

-

Use of adrenaline free local anaesthesia to avoid adverse reactions in coronary patients and the chance of reactive vasodilatation causing secondary haemorrhage (which can occur in adrenaline containing local anaesthetics)

-

Consider staged extractions for the control of intra-operative bleeding

-

Thorough curettage for the removal of granulation tissue following extraction

-

Avoid the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories for pain management in this group of patients

-

In patients where there is a concern of increased intra-operative or post-operative bleeding, surgical interventions should be delayed until discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy

-

Where discontinuation of therapy is not possible, the patient's cardiology physician should be contacted to discuss management issues (especially for general anaesthesia cases where staged extractions are not feasible)

-

Clinicians should consider preoperative blood and coagulation profiles (ASPI test and ADP test) where there is a risk of increased bleeding, especially in vulnerable adults (such as the elderly or those with existing co-morbidities).

References

Milner, J, Hoffhines A . The discovery of aspirins antithrombotic effects. Tex Heart Inst J 2007; 34: 179–186.

Undas, A, Brummel-Ziedines, K, Mann K . Antithrombotic properties of aspirin and resistance to aspirin: beyond strictly platelet actions. Blood 2007; 109: 2285–2292.

Vane, J, Botting R . The mechanism of action of aspirin. Thromb Res 2003; 110: 255–8.

Mechanism of action of clopidogrel. Available at http://pharmacologycorner.com/animation-on-coagulation-physiology-and-the-mechanism-of-action-of-glycoprotein-iibiiia-antagonists/ (accessed February 2016).

Collaboration A. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002; 324: 71–86.

Payne, D, Hayes, P, Jones, C, Belham, P, Naylor, A, Goodall A . Combined therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin significantly increases the bleeding time through a synergistic antiplatelet action. J Vasc Surg 2002; 35: 1204–1209.

Robless P, Mikhailidis D, Stansby G . Systematic review of antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of myocardial infarction, stroke or vascular death in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Br J Surg 2001; 88: 787–800.

Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. Available online at http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnf/current/2-cardiovascular-system/29-antiplatelet-drugs/aspirin-antiplatelet (accessed February 2016).

Herbert, J, Savi P . P2Y12, a new platelet ADP receptor, target of clopidogrel. Semin Vasc Med 2003 3: 113–122.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Prasugrel with percutaneous coronary intervention for treating acute coronary syndromes. 2014. Guideline TA317.

Angiolillo, D, Suryadevara, S, Capranzano, P, Bass T . Prasugrel: a novel platelet ADP P2Y12receptor antagonist. A review on its mechanism of action and clinical development. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2008; 9: DOI: 10.1517/14656566.9.16.2893

Dezsi, B, Koritsanszky, L, Braunitzer, G, Hangyasi, D, Dezsi C . Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel: a comparative examination of local bleeding after dental extraction in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015; 73: 1894–1900.

NICE, 2015. Clinical knowledge summaries. Available online at http://cks.nice.org.uk/antiplatelet-treatment#!topicsummary (accessed January 2016).

Brennan M, Valerin M, Noll J et al. Aspirin use and post-operative bleeding from dental extractions. J Dent Res 2008; 87: 740–744.

Nooh N . The effect of aspirin on bleeding after extraction of teeth. Saudi Dent J 2009; 21: 57–61.

Sumanth K N, Prashanti E, Aggarwal H, Kumar P, Kiran Kumar Krishanappa S . Interventions for managing post-extraction bleeding (Protocol). 2015. The Cochrane Library; 10: DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011930.

Girotra C, Padhye M, Mandlik G et al. Assessment of the risk of haemorrhage and its control following minor oral surgical procedures in patients on anti-platelet therapy: a prospective study. Int J Oral Max Surg 2014; 43: 99–106.

Lillis T, Ziakas A, Koskinas K, Tsirlis A, Giannoglou G . Safety of dental extractions during uninterrupted single or dual antiplatelet treatment. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108: 964–967.

Napenas J, Hong C, Brennan M, Furney S, Fox P, Lockhart P . The frequency of bleeding complications after invasive dental treatment in patients receiving single and dual antiplatelet therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 2009; 140: 690–695.

Park M, Her S, Kwon J . Safety of dental extractions in coronary drug-eluting stenting patients without stopping multiple antiplatelet agents. Clin Cardiol 2012; 35: 225–230.

Gröbe, A, Fraederich, M, Smeets et al. Post operative bleeding for oral surgery under continued clopidogrel antiplatelet therapy. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: DOI: 10.1155/2015/823651.

Olmos-Carrasco O, Pastor-Ramos V, Espinilla-Blanco R. Haemorrhagic complications of dental extractions in 181 patients undergoing double antiplatelet therapy. J Oral Max Surg 2015; 73: 203–210.

Cañigral A, Silvestre F, Cañigral G, Alos M, Garcia-Herraiz A, Plaza A . Evaluation of bleeding risk and measurement of methods in dental patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2010; 15: 863–868.

Omar H, Socias S, Powless, R et al. Clopidogrel is not associated with increased bleeding complications after full-mouth extraction: A retrospective study. J Am Dent Assoc 2015; 146: 303–309.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nathwani, S., Martin, K. Exodontia in dual antiplatelet therapy: the evidence. Br Dent J 220, 235–238 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.173

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.173

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of local hemostatic efficacy after dental extractions in patients taking antiplatelet drugs: a randomized clinical trial

Clinical Oral Investigations (2021)

-

Post-extraction bleeding complications in patients on uninterrupted dual antiplatelet therapy—a prospective study

Clinical Oral Investigations (2021)

-

Combined aspirin and clopidogrel therapy in phacoemulsification cataract surgery: a risk factor for ocular hemorrhage?

International Ophthalmology (2020)

-

Pharmacology: Confounders for bleeding

British Dental Journal (2016)