Key Points

-

Highlights a disturbing trend of increasing hospital admissions for the treatment of dental conditions in children in England over a nine year period.

-

Most of the increased activity was attributable to a 66% increase in extractions due to caries.

-

The data highlights a major public health issue requiring further investigation.

Abstract

Objective To determine the pattern of hospital admissions for dental care of children and adolescents between 1997 and 2006.

Design Retrospective analysis of data from the Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) database (1 April 1997 to 30 March 2006) if the patient was aged up to 17 years old and their primary diagnosis was a dental condition.

Outcome measures Primary diagnosis, treatment provided, socioeconomic status.

Results There were 517,885 NHS episodes of care for dental conditions in 470,113 children. Over half of the admissions were primarily for dental caries and 80% of all the admissions involved extractions. The peak age for caries-related extractions was five years old. There was a steady increase in the annual number of episodes of care with most of the increased activity attributable to a 66% increase in extractions for caries. More episodes of care were provided for children who lived in relatively deprived areas compared to more affluent areas.

Conclusions Data from the HES highlights a major public health issue. Caries is a preventable disease yet the number of children being admitted for elective extractions of teeth due to caries was increasing yearly. Further investigation to determine some of the underlying reasons for this trend is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following the report of a steering group chaired by Dame Edith Körner, the Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) data warehouse was set up in 1987 to collect and use hospital activity information. Prior to this initiative only 10% of all admitted patient records in the National Health Service (NHS) were collected.

HES aims to collect a detailed record for each 'episode' of admitted patient care delivered in England by NHS hospitals (or delivered in the independent sector but commissioned by the NHS). In 2006-2007 this resulted in nearly 15 million episodes of care from 13 million admissions. Tables of data relating to admitted patient care in NHS hospitals in England are made available yearly, with the first dataset produced for 1989–1990. Each HES record contains a wide range of information about an individual patient admitted to an NHS hospital. This can include clinical information (eg diagnoses and operations) or more general information (eg age group, gender, ethnic category, place of residence). The main unit of recording is the Finished Consultant Episode (a period of admitted patient care under a consultant or allied healthcare professional within an NHS trust). To be recorded, patients must be admitted to a bed.

Recent HES data presented by Thomas et al.1 highlighted a worrying rise in the number of admissions for drainage of dental abscesses across all age groups. While they could only speculate on reasons for this rise, they did make the important point that an increase in hospital care for an essentially preventable condition constituted a major public health issue. This prompted us to look at hospital admissions for dental care in children, particularly for management of dental caries, as general anaesthesia is used to manage behaviour and anxiety. Therefore the aim of this study was to report on the pattern of hospital admissions in the NHS (England) for the dental care of children and adolescents.

Methods

Data on hospital activity were extracted from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database for the nine year period from 1 April 1997 to 30 March 2006. For the purpose of this investigation, data were extracted if the following inclusion criteria were fulfilled:

-

1

The patient was aged up to 17 years old (age last birthday) at the start date of admission, and

-

2

Their primary diagnosis was a dental condition (International Classification of Diseases 10th revision, ICD-10, codes K00 to K14 inclusive).

Once extracted, these data underwent validation checks and duplicate records were removed. Deprivation scores were allocated to each record based on quintiles of the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD).2 Descriptive tables of frequencies were generated. Inferential analyses were undertaken using the statistical software package STATA version 10 (Statacorp, USA). The associations between dependent variables and IMD quintiles were expressed as odds ratios and were calculated using a generalised estimating equations (GEE) approach in order to account for the 'clustering effect' caused by the fact that some children underwent multiple episodes of care and were therefore represented in more than one record in the database.

Results

General characteristics

There were in excess of half a million (517,885) NHS episodes of care for dental conditions in children in England over the nine year period. These episodes related to 470,113 individual children. The characteristics of these episodes are reported in Table 1. It can be observed that a little over half of the admissions were primarily for dental caries and that over 95% of admissions were elective.

Almost a quarter of episodes (127,848 = 24.69%) had additional diagnoses recorded. The most commonly recorded additional diagnoses were further dental problems (56,773 = 10.96%), asthma (22,374 = 4.32%), allergy (6,092 = 1.18%) and epilepsy (3,744 = 0.72%). The additional diagnoses were not mutually exclusive and some children had multiple additional medical problems listed.

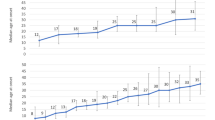

Approximately four fifths of episodes involved extractions (412,358 = 79.62%). Figure 1 illustrates the age profile of the children undergoing extractions and distinguishes between those having extractions because of dental caries and those having extractions for any other reason. The peak age for caries-related extractions among the admitted children was five years old, while the peak for non-caries extractions (predominantly orthodontic extractions) occurred later at age 13. Of those children who had extractions, the vast majority (94.42%) only underwent one extraction episode during the nine years under investigation. However, it can be seen from Table 2 that some children had multiple episodes involving extractions. In the worst case, one child received extractions on seven separate occasions over the nine year period.

Temporal changes

There was a steady increase in the annual number of episodes of care. This rose from 50,224 in the 1997 'HES year' to 64,521 in the 2005 'HES year', representing a 28% increase in volume of activity over nine years. Figure 2 indicates that the increased activity mostly resulted from an increase in extractions for caries (from 20,226 in 1997 to 33,553 in 2005), representing a 66% increase over nine years. The numbers of episodes each year for procedures other than extractions remained relatively stable. This was consistent across deprived or affluent groups (Fig. 3).

Relative deprivation

More episodes of care were provided for children who lived in relatively deprived areas compared to more affluent areas (Table 1). For example, twice as many episodes were provided to children in the most deprived quintile (154,353) than to children in the most affluent quintile (72,720). Relative deprivation of area of residence of the children was found to be linearly associated with the nature of their presentation, their medical history and the type and amount of treatment they received (Tables 3, 4, 5). There was a highly statistically significant trend for children living in more affluent areas to be less likely to present as an emergency than those living in more deprived areas. For example, children living in the most affluent areas were 33% less likely to present as an emergency than those in the most deprived areas. Children living in the most affluent areas were 75% less likely to present with caries than those in the most deprived areas. Similar comparisons show that they were 17% less likely to have asthma, 48% less likely to undergo extractions and 22% less likely to have multiple treatment episodes over the nine year period. However, the more affluent children were more likely to present with allergies (39% more likely for the most affluent compared to the most deprived) and also more likely to present with multiple dental problems (13% more likely for the most affluent compared to the most deprived).

Figure 4 shows data solely for those children who received extractions. Among these children there is a highly statistically significant association (p <0.001) between the number of times a child was admitted for extractions and the relative deprivation of their area of residence, with the more affluent children having fewer admissions for extractions on average.

Discussion

This study was based on analysis of HES data. HES states that 'Fluctuations in the data can occur for a number of reasons, eg organisational changes, reviews of best practice within the medical community, the adoption of new coding schemes and data quality problems that are often year specific. These variations can lead to false assumptions about trends.' Inferences made from these data follow; readers should bear the above statement in mind when reading them.

Before considering some of the implications of these data, we need to understand why these children were being admitted. The obvious reason for elective hospital admission of a child for dental care is that they require a general anaesthetic (GA); in this case presumably a 'day stay', as 92% of admissions were less than one day in duration. Interestingly, general anaesthesia was not recorded on the HES database for most of these hospital admissions (less than 6% of under-five-year-olds admitted for dental extractions). We believe that only the primary operation and diagnosis codes were being recorded, with supplementary fields left blank. It is difficult to hypothesise what other reasons there might be for hospital admissions in this group. For the purposes of this report we have assumed that most of the episodes of care (particularly extractions) were carried out under GA.

Over half of the admissions in the nine year period examined were for dental caries. This represents an average of 29,676 admissions per year, with most of them presumably having a GA for treatment. The majority of the children recorded were young, with five being the most common age recorded. The large number of young children requiring a hospital admission to manage dental caries every year is disturbing, however a more worrying finding was the increase in admissions reported: extractions for caries rose by 66% between April 1997 and March 2006.

There are several possible factors that could have contributed to the increase in hospital admissions for extraction of carious teeth. Pre-2000, a proportion of general anaesthetics were carried out in the primary care sector. Following publication of A conscious decision by the Department of Health,3 all GAs for dental treatment had to be carried out in a hospital. This may be a contributing factor toward the increase seen, however one might expect to see a similar trend in other dental procedures not related to caries (eg orthodontic extractions). This does not appear to be the case. Furthermore one might also expect to see a 'spike' in admission numbers following introduction of the new regulations in 2000, with a subsequent return to a steady state. Again, this does not appear to be the pattern seen.

The next contributory factor could be a general increase in caries levels across the population. This can be explored by looking at data from the British Association for Community Dentistry (BASCD) survey of five-year-olds in England. Data from the 1997/1998 BASCD survey4 reported a DMFT of 1.47 in this group, and this was unchanged in 2005/2006.5 However, the care index (FT/DFT) worsened over this time period, decreasing from 15% to 11%. This might suggest that the increase in hospital admissions is due to a reduction in restorative care provided for children in the primary care sector. Possible reasons for this reduction are complex and difficult to fathom. Children can present a barrier to treatment due to fear and anxiety, however this is unlikely to have changed over the nine year period. Other reasons for dentists providing less restorative care for children could include inadequate recompense for these procedures, inadequate training in the restorative management of children, failure of children to attend for care or inadequate provision of dental services for children. Again it is difficult to see why this should change over the time period analysed. Determination of the reason is outside the scope of this report.

Thomas et al.1 noticed an increase in severe abscesses in adults, which is analogous to the situation seen here of an increase in extractions for caries. They also noted that it was ongoing from 1998 (though they focused on an adult population) against a background of falling caries rates. They suggested this could be due to changes in service provision or perhaps in the failure of patients to attend for care.

The other issue highlighted by the HES statistics is the relationship between caries and socioeconomic status. This relationship is well established,6 however the HES dataset helps to illustrate what this means in terms of outcomes for children in lower socioeconomic groups. Twice as many episodes were provided to children in the most deprived quintile than to children in the most affluent quintile, and children living in more affluent areas were less likely to present as an emergency than those living in more deprived areas. The lower socioeconomic groups were therefore further disadvantaged as they were exposed to a greater risk of morbidity or even mortality as a result of being more likely to be admitted for management of dental caries.

Conclusions

Data from the HES highlights a major public health issue. Caries is a preventable disease. Interventions such as water fluoridation are well established and of proven efficacy. Treatment of caries in children is taught to all undergraduates and should be part of every general dental practitioner's routine dental practice. Why then are more and more children being electively admitted to hospital for extractions of teeth due to caries? If we presume that they are attending to have a dental general anaesthetic, then they are being exposed to an increased risk of morbidity and even mortality as a result of this intervention. The additional financial burden on the NHS of a hospital admission is also considerable. Further investigation to determine some of the underlying reasons for this disturbing trend are required.

References

Thomas S J, Atkinson C, Hughes C, Revington P, Ness A R. Is there an epidemic of admissions for surgical treatment of dental abscesses in the UK? BMJ 2008; 336: 1219–1220.

Nobel M, Wright G, Dibben C et al. Indices of multiple deprivation 2004. London: The Stationery Office, 2004. ISBN 1 851127 08 9.

Department of Health. A conscious decision. A review of the use of general anaesthesia and concious sedation in primary dental care. Report by a group chaired by the Chief Medical Officer and the Chief Dental Officer. London: Department of Health, 2000. Available online at http://www.dh.gov.uk/ en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/ DH_4074702.

Pitts N B, Evans D, Nugent Z J . The dental caries experience of 5-year-old children in the United Kingdom. Surveys co-ordinated by the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry in 1997/1998. Community Dent Health 1999; 16: 50–56.

Pitts N B, Boyles J, Nugent Z J, Thomas N, Pine C M . The dental caries experience of 5-year-old children in Great Britain (2005/6). Surveys co-ordinated by the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Community Dent Health 2007; 24: 59–63.

Tickle M, Williams M, Jenner T, Blinkhorn A . The effects of socioeconomic status and dental attendance on dental caries experience, and treatment patterns in 5-year-old children. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 135–137.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moles, D., Ashley, P. Hospital admissions for dental care in children: England 1997-2006. Br Dent J 206, E14 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.254

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.254

This article is cited by

-

Trends in dental caries of deciduous teeth in Iran: a systematic analysis of the national and sub-national data from 1990 to 2017

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

Evaluation of a caries prevention programme for preschool children in Switzerland: is the target group being reached?

BMC Oral Health (2021)

-

Childhood caries and hospital admissions in England: a reflection on preventive strategies

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

A retrospective analysis of hospitalisation for diseases of the pulp and periapical tissues in NHS Grampian 2011-2015: geographic, socioeconomic and increased primary care availability effects

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Socioeconomic and ethnic status of two- and three-year-olds undergoing dental extractions under general anaesthesia in Wolverhampton, 2011-2016

British Dental Journal (2019)