Abstract

Study design:

Retrospective observational study.

Objectives:

To investigate the study participation rate of patients with acute spinal cord injury (SCI) early during rehabilitation after conveying preliminary study information.

Setting:

Single SCI rehabilitation center in Switzerland.

Methods:

Newly admitted acute SCI patients receive a flyer to inform them concerning the purpose of clinical research, patient rights and active studies. Upon patient request, detailed study information is given. The rate of patients asking for detailed information (study interest) and the rate of study participation was evaluated from May 2013 to October 2014. Furthermore, the number of patients not withdrawing consent to the utilization of coded health-related data was determined.

Results:

The flyer was given to 144 of the 183 patients admitted during the observation period. A total of 96 patients (67%) were interested in receiving detailed information, and 71 patients (49%) finally participated in at least one study. The vast majority of patients (that is, 91%) did not withdraw consent for retrospective data analysis. An age over 60 years had a significantly (P⩽0.023) negative effect on study interest and participation, and the consent rate to retrospective data analysis was significantly (P<0.04) lower in patients older than 75 years. Study interest and participation were reduced more than 5 and 14-fold, respectively, in patients older than 60 years.

Conclusions:

The relatively low (approximately 50%) study participation rates of acute SCI patients should be considered when planning clinical trials. The recruitment of patients older than 60 years may be reduced substantially.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a growing number of clinical studies involving patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI): for example, the number of observational studies has doubled over the last decade.1 Investigations of neuroprotective or -regenerative therapies require large numbers of patients to detect any, most likely moderate, neurologic improvements. Moreover, moderate neurologic improvements may get masked by spontaneous neurologic recovery early after injury, especially in patients with incomplete SCI.2, 3, 4 Thus, larger sample sizes are required or potential study participants have to be excluded. Furthermore, primarily eligible patients have to be excluded as a result of severe concomitant injuries (for example, head trauma) or comorbidities, mental disorders, psychoactive substance abuse or communication barriers (for example, foreign languages), which preclude obtaining informed consent or represent confounding factors.3, 5

The reported average number of participants enrolled in SCI trials is larger than 100.1 Thus, the recruitment of sufficient numbers of acute traumatic and preferably motor complete SCI patients for clinical studies represents a challenge in the light of the relatively low incidence of SCI. The annual incidence of traumatic SCI ranges from 8 to 49 patients per million population in different high-income countries around the world.6 In Switzerland, for example, the reported incidence ranges from 17 to 20 per million,7 and thus, 140 to 160 individuals sustain traumatic SCI annually. The study registry ‘ClinicalTrials.gov’ (https://clinicaltrials.gov/, United States National Institutes of Health, accessed 1 November 2014) currently lists 26 open studies regarding SCI in Switzerland. Thus, a competition for enrollment of patients can develop,3 and patients may get overwhelmed by multiple requests for study participation early after injury while they are in the process of coping with this life-altering event. With the purpose not to overburden patients with multiple requests for study participation early after injury, we have established a recruitment process using a flyer to inform patients concerning active studies at our institution.

An estimation of the number of patients who can be recruited at a certain institution is crucial for planning clinical studies. We have therefore evaluated the study participation rate of patients with acute SCI early during rehabilitation after conveying preliminary study information using a flyer.

Materials and methods

Setting

This investigation was carried out in a SCI rehabilitation center with 140 beds and manifold research activities including several studies with acute, mainly traumatic, SCI patients. No health-related data were collected and thus approval from the competent ethics committee was not required according to Swiss federal law (Law on Human Research Art. 2).

Recruitment process and information flyer

The admission list of our institution is screened weekly for patients with acute SCI being admitted for primary rehabilitation. Identified patients are contacted as soon as their clinical condition allows (assessed by the responsible physician). Patients admitted to the intensive care unit are contacted after they have been transferred to the ward. In the course of a short bedside visit, patients are informed concerning the purpose of clinical research, patient rights and active studies they would qualify for by one of the three staff from the Clinical Trial Unit at our center. Furthermore, patients receive information about the utilization of coded health-related data for research purposes (retrospective data analysis). They have to notify the Clinical Trial Unit if they do not want their data to be used for future retrospective studies. At the end of the visit, a flyer containing the conveyed information and a short description of the aims of active studies is given to the patients. The flyer is available in German, French, Italian and English. Patients are not asked to decide on study participation based on the information in the flyer, but to convey whether they are interested in receiving detailed study information. If a patient requests detailed study information, the investigator is notified and will approach the patient. Patient recruitment for studies requiring enrollment during the intensive care unit period is carried out separately to the above-described process.

Collected data

The time period from May 2013 to October 2014 was evaluated. During this period, two multicenter observational cohort studies, two to three observational or cross-sectional studies and one small interventional trial were active for patients with acute traumatic SCI. Apart from the interventional trial, inclusion criteria were broad, and there were few exclusion criteria. Personal characteristics were collected. The severity of SCI was classified using the American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS). The time from injury to admission, transfer from the intensive care unit to the ward as well as delivery of the research information flyer was determined. Furthermore, the rate of patients asking for detailed study information (study interest) and the rate of study participation was collected. The number of patients not consenting to the utilization of coded health-related data was also determined.

Statistical analysis

The data were calculated as medians and 95% confidence intervals (CI) when appropriate. The Chi-square test was used to investigate differences in observed frequencies between groups (gender, injury etiology and injury severity). Comparisons between independent samples were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The effects of gender, age, injury level and severity, injury duration and injury etiology (that is, traumatic/nontraumatic) on study interest, study participation and consent to retrospective data analysis were investigated using binary logistic regression analysis. The interaction term etiology*gender*age was included in the model. The age was grouped using 15-year increments.8 According to international recommendations, injury level and severity were classified into four groups: (i) AIS D, (ii) AIS A–C paraplegia, (iii) AIS A–C low-level tetraplegia (C8-C5) and (iv) AIS A–C high-level tetraplegia (C4-C1).8 The statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 18.0.3, IBM, Somers, NY, USA). A P-value of ⩽0.05 was considered significant.

Results

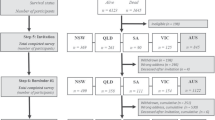

From 1 May 2013 to 15 October 2014, a total of 183 patients with acute SCI were admitted to our institution for primary rehabilitation. The research information flyer was given to 144 patients. The reasons for not delivering the flyer to some patients are presented in Table 1. Poor clinical condition or insufficient cognitive abilities were the most common reasons.

Patients’ characteristics including gender, injury etiology (that is, traumatic or nontraumatic) and injury severity are presented in Table 2. The majority of the patients were male (that is, 103/144, 72%) and had sustained traumatic SCI (that is, 94/144, 65%) (Table 2). The median age at the time of SCI was 54 years (95% CI 50–60 years, range 16–88 years). Women were significantly (P=0.01) older than men. Furthermore, patients with nontraumatic SCI were significantly (P<0.001) older compared with patients with traumatic SCI (Table 3).

Patients had been admitted a median 11 days (95% CI 8–14 days) after SCI. Patients with nontraumatic SCI had been admitted significantly (P=0.014) later (median 15 days) than those with traumatic SCI (median 8 days) (Table 3). The flyer was delivered to the patients a median 37 days (95% CI 33–42 days) after SCI and a median 22 days (95% CI 20–25 days) after admission. In tetraplegic patients, significantly (P=0.015) more time had elapsed from admission to flyer delivery, compared with paraplegic patients (Table 3).

A total of 96 patients (67%) were interested in receiving detailed study information, and 71 patients (49%) finally participated in at least one study (Table 4). Thus, approximately four patients consented to study participation every month. The number of patients not withdrawing consent for the utilization of data for retrospective analysis was 131 (91%) (Table 4). The patients’ age had a significant effect on study interest (P=0.002), study participation (P<0.001) and consent to retrospective data analysis (P=0.03) (Table 5). The rate of study interest, study participation and consent to retrospective data analysis for the different age groups are presented in Table 6. The study interest and the study participation in the age group 46–60 years were significantly (P⩽0.023) greater compared with the older age groups (Table 6). The odds of having an interest in studies or participating in a study were reduced more than 5 and 14-fold, respectively, in patients older than 60 years (Table 6). The odds of consenting to retrospective data analysis were significantly (P⩽0.023) reduced 25 times in patients older than 75 years compared with the age group 46–60 years (Table 6).

Discussion

An estimation of the number of patients who can be recruited realistically at a study center is crucial for planning clinical studies. Typically, the total number of patients with the condition under investigation who are admitted to the study center is considered, even though only a fraction of these patients is eligible and consents to study participation. In the present setting, 79% (that is, 144/183) of admitted patients with acute SCI were eligible for at least one clinical study over a time period of 17.5 months. Poor clinical condition, specific study exclusion criteria and language barrier were the main reasons precluding eligibility. In a Canadian primary spinal trauma referral center, a potential 70% enrolment rate of patients with acute traumatic SCI for hypothetical clinical trials was determined.5 The slightly lower eligibility rate, in comparison with the present study, may be the result of only including patients with traumatic SCI and different exclusion criteria. Naturally, not all eligible patients take part in a study. In the present investigation, 49% (that is, 71 patients) of the eligible patients consented to study participation. The comparison of participation rates between studies turns out to be futile as a result of how differently recruitment, screening and participation rates have been determined and the various recruitment and screening procedures. For instance, Craven et al.9 have reported the screening to recruitment ratio for different study designs and intervention types (ranging from 5:1 to 2:1). The ratio was calculated by dividing the number of consenting patients who underwent screening by the number of eligible patients enrolled in the study. This ratio would help to assess selection bias and plan studies.

In the present study, 67% of the eligible patients were interested in receiving detailed study information. Other authors, who have investigated the willingness of patients in participating in hypothetical10, 11, 12, 13 or real trials,14, 15 have reported similar rates, ranging from 50 to 66%. However, only 74% (71/96) of the interested patients in our investigation actually consented to participate.

Different factors affect the interest in study participation and the consent to participation: we have observed a more than 5 and 14-fold reduction in study interest and participation, respectively, in patients older than 60 years. The greatest interest and participation rates were observed in the age group 46–60 years. Interestingly, interest and participation rates in the younger age groups (16–30 years and 31–45 years) were also lower, but only the rates in patients from 31 to 45 years were significantly reduced. The reasons for the reduced interest and participation rates in younger patients remains unclear and warrants further investigation. In contrast, injury etiology, level, severity and duration as well as gender did not have a significant effect. Maida et al.11 have reported that the willingness of patients with multiple sclerosis to participate in a trial was influenced by their age, whether they had children or already had participated in a trial, the expectation to have a greater chance of cure and the wish to contribute to medical research. Improvement of one’s own treatment or altruistic motivation are common considerations for study participation.10 In contrast, invasive procedures and the fear of side-effects reduce study participation rates.10 Other common reasons for declining participation are insufficient time resources and poor physical or mental condition.10 We were not able to investigate the reasons for participation refusal in our cohort, because they had not been documented. There were only anecdotal reports such as: ‘rehabilitation schedule too busy’, ‘not relevant/no personal benefit’, ‘too ill’, ‘too old for this kind of undertaking’ and ‘overwhelmed with overall situation’. There was no record that patients were overwhelmed with the presentation of several studies in the flyer. Patients were not asked to decide on study participation based on the information in the flyer, but to convey whether they wished to receive detailed study information. However, some patients may have been overwhelmed with the information in the flyer and thus declined study participation.

In the present study, patients older than 75 years were 25 times more likely to withdraw consent for retrospective data analysis. Overall, the consent to retrospective data analysis was greater than 90%. The utilization of coded health-related data for retrospective analysis does not seem to generally raise concerns in patients.

Patients had received the research information flyer on average 22 days after admission, 37 days after SCI. Tetraplegic patients had received the flyer significantly later (that is, 26 days after admission) than paraplegic patients (that is, 20 days after admission), because they stayed longer in the intensive care unit. Supplementing usual study information with a booklet on clinical trials has been reported to have little or no impact on the recruitment rate.16 However, the purpose of the research information flyer was not to increase study recruitment, but to spare patients from multiple requests for study participation at short intervals.

The presented data concerning study participation rates of patients with acute SCI early during rehabilitation using a research information flyer are site-specific with limited generalizability. However, the demographic characteristics of the investigated cohort are comparable with the characteristics of acute SCI patients in general,6, 17, 18, 19 and the observed study interest and participation rates are in accordance with previously reported data.5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 The limitations of the present study also include that our investigation is specific to the rehabilitation stage and does not include the first 2 weeks after injury. Patients had been admitted 11 days after SCI, whereas in some SCI centers, the majority of patients are admitted within 48 h after injury.5 The odds ratio values for age and gender should be interpreted with caution because of the wide CI. Furthermore, it was not possible to investigate the effect of the study design (for example, interventional, observational) on study interest and participation, and there was no outcome variable for assessing patient protection as a result of using the research information flyer. Finally, it was not possible to assess the effect of the flyer on recruitment rates, because no data were available for the period prior to the flyer.

A relatively low (approximately 50%) consent rate should be expected and considered when planning clinical trials. In the present setting, approximately four patients consented to study participation every month. Considering the reported average number (that is, >100) of participants enrolled in SCI trials,1 it is not surprising that many investigators do not achieve their original recruitment target and have to extend the study duration.20 Aside from patient-related factors, time constraints and an indifferent attitude of investigators towards clinical trials become increasingly prevalent and can affect recruitment negatively. Delivering preliminary study information to patients in the form of a flyer may not increase recruitment, but spares patients from multiple requests at short intervals. In contrast, the lack of patient–physician interaction may reduce recruitment.11 Acute SCI patients may not represent a so-called vulnerable population, but facing the consequences of paralysis, they may decide to participate in a study because out of desperation, they grab on to anything promising a benefit, disregarding any potential risks. The screening and recruitment strategy we have instigated is an option to respect the ethical obligations when recruiting acute SCI patients for studies.

In conclusion, the relatively low (approximately 50%) study participation rates of acute SCI patients should be considered when planning clinical trials. The recruitment of patients older than 60 years may be reduced substantially.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Sorani MD, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC . A quantitative analysis of clinical trial designs in spinal cord injury based on ICCP guidelines. J Neurotrauma 2012; 29: 1736–1746.

Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 190–205.

Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW, Lammertse D, Kalichman M, Rask C et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP Panel: clinical trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and ethics. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 222–231.

Velstra IM, Bolliger M, Tanadini LG, Baumberger M, Abel R, Rietman JS et al. Prediction and stratification of upper limb function and self-care in acute cervical spinal cord injury with the graded redefined assessment of strength, sensibility, and prehension (GRASSP). Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2014; 28: 632–642.

Lee RS, Noonan VK, Batke J, Ghag A, Paquette SJ, Boyd MC et al. Feasibility of patient recruitment into clinical trials of experimental treatments for acute spinal cord injury. J Clin Neurosci 2012; 19: 1338–1343.

Singh A, Tetreault L, Kalsi-Ryan S, Nouri A, Fehlings MG . Global prevalence and incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6: 309–331.

Brinkhof M . Swiss Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study (SwiSCI): aims, design and first results. European Spinal Cord Injury Federation Congress 2013. Nottwil, Switzerland.

DeVivo MJ, Biering-Sorensen F, New P, Chen Y . Standardization of data analysis and reporting of results from the International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 596–599.

Craven BC, Balioussis C, Hitzig SL, Moore C, Verrier MC, Giangregorio LM et al. Use of screening to recruitment ratios as a tool for planning and implementing spinal cord injury rehabilitation research. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 764–768.

Bevan EG, Chee LC, McGhee SM, McInnes GT . Patients' attitudes to participation in clinical trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1993; 35: 204–207.

Maida S, Dalla Costa G, Rodegher M, Falautano M, Comi G, Martinelli V . Overcoming recruitment challenges in patients with multiple sclerosis: Results from an Italian survey. Clin Trials 2014; 11: 667–672.

Graham A, Goss C, Xu S, Magid DJ, DiGuiseppi C . Effect of using different modes to administer the AUDIT-C on identification of hazardous drinking and acquiescence to trial participation among injured patients. Alcohol Alcohol 2007; 42: 423–429.

Myles PS, Fletcher HE, Cairo S, Madder H, McRae R, Cooper J et al. Randomized trial of informed consent and recruitment for clinical trials in the immediate preoperative period. Anesthesiology 1999; 91: 969–978.

Harris TJ, Carey IM, Victor CR, Adams R, Cook DG . Optimising recruitment into a study of physical activity in older people: a randomised controlled trial of different approaches. Age Ageing 2008; 37: 659–665.

Ives NJ, Troop M, Waters A, Davies S, Higgs C, Easterbrook PJ . Does an HIV clinical trial information booklet improve patient knowledge and understanding of HIV clinical trials? HIV Med 2001; 2: 241–249.

Treweek S, Lockhart P, Pitkethly M, Cook JA, Kjeldstrom M, Johansen M et al. Methods to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e002360.

Thompson C, Mutch J, Parent S, Mac-Thiong JM . The changing demographics of traumatic spinal cord injury: An 11-year study of 831 patients. J Spinal Cord Med 2014; 38: 214–223.

McKinley WO, Seel RT, Hardman JT . Nontraumatic spinal cord injury: incidence, epidemiology, and functional outcome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 619–623.

National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. J Spinal Cord Med 2013; 36: 1–2.

McDonald AM, Knight RC, Campbell MK, Entwistle VA, Grant AM, Cook JA et al. What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials 2006; 7: 9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krebs, J., Katrin Brust, A., Tesini, S. et al. Study participation rate of patients with acute spinal cord injury early during rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 53, 738–742 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.73

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.73

This article is cited by

-

Immunomodulation for primary prevention of urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injury during primary rehabilitation: protocol for a randomized placebo-controlled pilot trial (UROVAXOM-pilot)

Trials (2021)

-

Process evaluation of a tailored work-related support intervention for patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2020)

-

The challenge of recruitment for neurotherapeutic clinical trials in spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2019)