Abstract

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at risk of becoming overweight or obese due to treatment effects and/or post-treatment behaviors. Parents are key agents influencing child diet and physical activity (PA), which are modifiable risk factors for obesity. A systematic literature review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines was undertaken to evaluate current interventions that include diet and PA elements for CCS to determine if and to what extent parents were included, and whether parent involvement had a significant effect on behavioral outcomes or adiposity. A total of 2,386 potential articles were reviewed and 25 individual studies fulfilled inclusion criteria. Parental involvement was classified into three categories and varied across studies, although most had indirect or no parental involvement. The studies that included direct parental involvement showed positive outcomes on a variety of measures suggesting that increasing parental involvement in interventions for CCS may be one way to promote long-term lifestyle changes for pediatric cancer patients. However, additional research directly addressing parental involvement in obesity prevention and treatment among CCS is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are a growing population with over 100,000 survivors under age 19 living in the United States as of January 2014 (1). In the last 30 y, treatments have improved survival rates for childhood cancer patients from 58 to 83% (1). However, CCS are experiencing a host of post-treatment sequelae, including increased risk of becoming overweight or obese due to effects of their treatment and unhealthy lifestyle practices (2,3,4,5,6). Obesity potentially modifies the iatrogenic cardiovascular, pulmonary, and second malignancy effects of treatment (7,8), emphasizing the need for obesity prevention among CCS.

Modifiable risk factors for obesity include dietary intake and physical activity (PA). While the majority of research on obesity and pediatric cancer survivorship has focused on acute lymphocytic/lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), several studies have demonstrated poor dietary and PA behaviors in patients and survivors across different cancer diagnoses (4,5,6). Despite CCS’ risk factors for obesity and other chronic conditions (i.e., cardiovascular disease), CCS are not more likely to adhere to diet and PA recommendations than the general population, despite their increased risk for associated chronic conditions (9,10). On average, CCS consume excessive calories (4), inadequate folate, calcium, and iron (4,5) and do not meet the national minimal PA guideline of 60 min of activity per day (5,11).

In noncancer populations, parents and caregivers have been shown to influence their children’s dietary habits (12,13) and PA levels (14). The socioecological model specifies the multiple layers that influence childhood obesity including both individual and environmental factors (15). Thus, parent characteristics, household characteristics, and parental perceptions of food and PA environments can be significant contributors to childhood obesity (15). Parents influence their children both by their parenting style and context-specific parenting practices. Parenting style describes the emotional climate that one establishes during interaction with their child, based on individual values and actions (16), whereas parenting practices are goal-oriented behaviors used to influence a child’s actions in a specific context (such as eating or exercising) (16). Reviews of parental involvement in diet and PA interventions for healthy children found higher intensity, direct parental involvement in such programs was promising, though the number of studies were limited (17,18). Parental involvement increased success of weight management studies targeting children/adolescents in noncancer settings (19,20). These issues have not yet been examined among CCS. This review explores two main research questions (i) To what extent have parents of CCS been involved in CCS diet and PA interventions? and (ii) Does parental involvement indicate better outcomes in diet and PA interventions for CCS?

Results

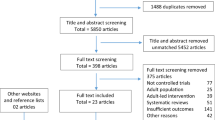

The search strategy identified 2,386 articles ( Figure 1 ). After the initial titles and abstracts were screened, 84 articles were retrieved for full text review. Of those, 30 articles met the inclusion criteria for review. Five of these were secondary analysis or follow up reports on already included studies, so they were combined with the original publication. This resulted in a total of 25 unique interventions to be included. A summary of characteristics of these studies is presented in Table 1 . While diet was included as part of five of the interventions identified, most studies focused exclusively on PA through exercise classes.

Scheme depicting the search methodology for this review. Combinations of keywords were entered into the three databases; only papers from peer-reviewed journals were included. Keywords (combinations of) included: infant, child, adolescent, pediatric, survivor, neoplasms, cancer, leukemia, cns, tumor, carcinoma, health behavior, health promotion, health attitudes, health practice, health knowledge, intervention, evaluation studies, program evaluation, validation studies, exercise movement techniques, exercise therapy, exercising, physical activity, physical exertion, swimming, nutrition, nutrition therapy, nutrition surveys, child nutrition sciences, diet, feeding behavior, and eating. The resulting articles were consolidated into a single document and duplicate articles removed. The titles and abstracts were screened for content. Papers that were off topic, targeted the wrong population or were not intervention studies were removed. The full texts of remaining studies were reviewed based on the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included unclear population, incomplete or lack of outcome data and unrelated primary outcomes.

We assessed parental involvement for each individual study. Nearly half of the total studies did not include parental involvement (21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34). Eleven studies were characterized as using indirect parental involvement (35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47). Three studies used direct parental involvement (48,49,50,51). None of the studies directly compared interventions with and without parental components. All studies were combined and categorized by type of parental involvement to determine if different levels of involvement had an impact on reported results ( Table 2 ). Outcomes were categorized by positive or mixed results and displayed with study characteristics by level of parental involvement. Positive results indicated that changes occurred in the desired direction. Mixed results indicate that there were some positive changes, but only among one subgroup (e.g., girls but not boys) or only for one of the outcome measured (e.g., BMI improved but not waist circumference). This method has been previously used to assess parental impact on intervention results (17). As the studies varied in outcome measures, the results were ordered into broader categories including diet, PA, fitness, anthropometric, and metabolic outcomes.

No Parental Involvement

Eleven studies had no parental involvement (21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34). Parents were only mentioned in these studies for consenting purposes or to serve as proxies for self-reporting behavior data. Of these papers, none positively impacted anthropometric or metabolic outcomes ( Table 2 ). However, 85% of the studies that collected fitness data reported positive outcomes and 71% of studies that collected PA data reported positive outcomes. Only one study included a diet measure in the form of a behavior questionnaire (33,34) and reported mixed outcomes, i.e., a significant reduction of junk food consumption in the intervention group with no other significant dietary improvements reported (34).

Indirect Parental Involvement

Eleven studies used indirect methods to engage parents in the interventions by sending materials home to parents, inviting parents to attend sessions with their children, enrolling parental support, and/or providing assignments to parents that required a response (parent satisfaction questionnaires) or action (active parent observation of home interventions) (35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47). Of the three indirect parental involvement studies that gathered diet data, one showed mixed outcomes, with improvements in total calorie and carbohydrate intake, but only among older participants (>14 y old) (39). Of the indirect studies that used anthropometric measures, the majority (57%) showed no impact, 14% had mixed results and 28% demonstrated positive impact. Of the indirect studies that measured fitness, 67% showed positive impact. Fifty percent of indirect studies that used PA measures showed improvements in outcomes.

Direct Parental Involvement

Only three studies used direct strategies to engage parents (48,49,50,51). One study included 75 cancer survivors aged between 11–21, with 38 randomized to the intervention group and 37 to a wait-listed control. In this study design (50,51), parents were shown a 20-min video explaining the program and were given the same study materials as their children to discuss in a group setting (allowing the parents to connect with each other as well as fully understanding the intervention). Parents were engaged in the development of the program by offering their opinions in preliminary focus groups. This study focused on bone health through healthy eating habits and found participants that attended the half-day workshop reported higher calcium intake than the control (51).

In the other two studies, parents were directly targeted for parent-only activities, though these were not necessarily related to specific parenting style advice (48,49). These studies focused on exercise training both at home and in the hospital. They engaged parents not only by having them complete surveys and serve as proxies for their children, but also requiring at least one parent to physically attend exercise sessions with their children (48,49).

One exercise study included children under 18 on active treatment for ALL (48). This nonrandomized pilot study had a standard care control group of 10 children and an intervention group of 12 children that received a home based exercise training course. While the main outcome of interest was fatigue, researchers also measured PA stage of change after the 6-wk intervention and found participants changed their intent to practice PA from the “contemplation” and “preparation” stages to ‘‘action” and “maintenance” stages, although these effects lessened at the 1 mo follow up. This study also included a measure of perceived exertion (OMNI walk-run scale) but did not report results (48).

Tanir and Kuguoglu (49) used direct parent involvement in an intervention for ALL survivors aged 8–12. Nineteen children were randomized to an intervention group receiving both hospital based and home based exercise sessions as well as educational pamphlets and biweekly phone calls with research staff. Twenty-one children were randomized to a standard care control. The main outcome of this 3-mo study was quality of life, but researchers also examined fitness and metabolic measures. Participants showed significant improvements in hemoglobin and hematocrit at postintervention and improved physical fitness as indicated by the 9 min walk run test, timed up and go (TUG) and timed up and down stairs (TUDS) tests and dynamometer (strength test) (49).

Discussion

This is the first review to examine parental involvement in diet and PA studies in CCS. Of 25 diet and/or PA interventions targeting child and adolescent CCS, 11 studies did not report parental involvement in the intervention, 11 studies reported indirect parental involvement and three studies reported direct parental involvement. Studies with no or indirect parental involvement had similar amounts of success, both lower than direct parental involvement, which reported improvements in all study measures. However, only three studies directly engaged parents, and they had relatively small sample sizes, did not include anthropometric measures, and were not all randomized controlled trials, which limits our ability to draw firm conclusions about the role of directly engaging parents in lifestyle interventions for pediatric CCS.

In general, studies focusing on promoting change in lifestyle behaviors in the CCS population were limited. Of the 11 studies that included anthropometric measures, only three demonstrated any positive change and each had a very different approach. The majority of eligible studies focused on exercise interventions and demonstrated moderate success with regard to fitness and PA behavior outcomes, but were likely underpowered given their small sample sizes and variable study designs. Studies showing fitness improvements included organized aerobic training sessions at least once a week over several weeks. Similarly, studies that demonstrated improved PA behavior included organized PA sessions either through formal training classes, games, sports or other physical leisure activities.

Despite the limited number of evaluation studies targeting lifestyle changes, CCS interest in healthy eating and PA interventions has been demonstrated in several survey studies on mixed diagnoses groups of survivors (5,11,52). Two studies found CCS were interested in participating in these programs with a parent (5,52). Such findings highlight the potential benefit of parental involvement during interventions and may assist with recruitment of participants in health behavior interventions.

Published CCS lifestyle interventions took place in a variety of settings including the participants’ homes, at community locations and also in hospitals/care facilities. Some hospital-based exercise studies, though small, measured successful outcomes (43,44) but long-term hospital-based interventions present a set of challenges to providers, as most hospitals are not equipped with full gyms and trained staff. Also, CCS may not be able to or not interested in returning to a hospital setting for this type of intervention. Therefore, transition into community or home-based activities focused on long-term fitness goals and lifestyle change is a practical evolution for hospital-based interventions. However, at-home lifestyle behavior change programs need to be carefully developed in conjunction with input from the end users, CCS and parents, to ensure parents have the tools to promote the continued progress of study subjects (53). The home component of one exercise program was described as “boring” by participants and thus, subjects could not be motivated to finish the intervention (46); another home-based study found declining levels of PA after the formal intervention ended (38). Parents may be an avenue for promoting sustained behavior change and motivation to complete home-based interventions.

Adding a parental involvement component may improve health promotion interventions for CCS. One review noted an increase in emotional closeness over time for many families and a perceived deepening bond between parents and the sick child (54). No relationship between parental involvement and participant age range, stage of treatment or diagnosis could be determined given the limited number of studies. Furthermore, some research has shown that parents may remain involved in the healthcare of CCS even into adulthood (55). Therefore, as CCS continue to experience increased health risks, including obesity, parental involvement should not be overlooked in lifestyle interventions during later treatment that target children or adolescents.

The few studies that used direct parent involvement in this review may offer strategies to effectively engage parents in interventions. These strategies include using parent focus groups to develop interventions, discussing intervention materials and structure with parents in a group setting, and creating parent-specific activities (48,49,50,51).

Parents of CCS face unique psychological challenges when they want to influence their child’s diet and PA behaviors. A systematic review found recurring themes of overindulgence, and spoiling of children on and off active treatment across a range of diagnoses, with parents perceiving their sick child as vulnerable and disadvantaged (54). A study of parents of children being treated specifically for ALL, one of the most common pediatric cancers, showed that these trends of increased overprotection, emotional feeding, and varying amounts of discipline were associated with increased junk food consumption and decreased fruit and vegetable consumption (56). CCS parents are also more likely to be overprotective and at times employed a monitoring and a restrictive parenting style (4). Higher levels of parent overprotection and perceived child vulnerability were associated with lower CCS quality of life (57). Parents being over protective may also lead to restricting children from participating in physical activities that these parents deem as risky (58). One exercise study suggested parental overprotectiveness needed to be addressed in future program design given the negative short-term effects of increasing exercise (i.e., fatigue and muscle soreness) to prevent subject dropouts (46).

CCS parents experience psychosocial issues related to their child’s cancer and treatment, in addition to the everyday stresses of parenthood (58,59,60). Parenting stress has been associated with poor social and behavioral adjustment in CCS (61,62,63). Thus, CCS parents may benefit from training in effective parenting practices to minimize overprotection and stress, while being cognizant of unique household dynamics in CCS families.

Limitations of this review include the fact that this is a developing field of research with few studies addressing the research question. Several identified articles were feasibility studies with small numbers of participants, limited control groups and limited evaluation measurements. These structural issues limited attempts to grade the quality of this literature. Varying outcome measures across studies also made comparison of results difficult. Overall, while parental involvement is important in obesity interventions of children without cancer, it has not been adequately studied in CCS interventions. This review identifies the need to evaluate whether parental inclusion in diet and exercise interventions for CCS would help reduce obesity risk in this vulnerable population, with the preliminary studies suggesting it might.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist was followed to present study findings (Supplementary Table S1 online) (64). The literature review was conducted in July 2015 using electronic databases: Scopus, Medline (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), and Web of Science to identify articles reporting diet and PA change interventions that targeted child and adolescent CCS. Key search terms included: infant, child, adolescent, pediatric, patient, survivor, intervention, neoplasms, health behavior, physical activity, nutrition therapy/surveys, diet, feeding behaviors, and eating. Articles were restricted to those published in peer-reviewed journals in English. As no protocol currently exists, a librarian experienced in conducting systematic and scientific reviews evaluated and verified the search strategy.

Publications from the initial search were reviewed for inclusion first based on title and abstract. Remaining full text articles were reviewed and citations from relevant articles were searched for further studies that met the inclusion criteria. This process was repeated by a second reviewer with a random sample of 25% of the originally sourced articles. The articles selected for inclusion were 100% concordant across the two reviewers. No human subject’s research was conducted as part of this review article so institutional review board approval was not necessary.

Inclusion criteria were (i) intervention or feasibility studies targeting diet, PA (PA behavior in general or fitness through exercise classes) or both; (ii) included CCS on or off treatment into young adulthood up to age 30 (study inclusion age starting <18); and (iii) measured changes in fitness, PA, diet, anthropometric or metabolic measures. Anthropometric measures included: weight, BMI, BMI-z scores, waist circumference, and/or body composition. Metabolic measures included: cholesterol, triglycerides, blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C, and insulin measures. Exclusion criteria were studies that (i) targeted only adult survivors of childhood cancer (study inclusion age starting at ≥18) or (ii) did not report on diet, PA, anthropometric or metabolic outcomes.

Components for each type of intervention were examined (i.e., exercise classes only or multicomponent interventions) and level of parental involvement assessed for the selected study. Based on published studies (17,18), we initially grouped parental involvement into the following categories with slight modifications: none (no parental involvement at all or parents were only consented or used as proxies for self-report measures), indirect 1 (provision of information to parents that did not require a response), indirect 2 (invitations to parents and children to attend activities sponsored by the intervention such as family days), indirect 3 (assignments given to parents including active parent observation or parent satisfaction assessments), direct 1 (parent attendance requested/required at intervention sessions and/or parents active in program development), and direct 2 (parent participation requested/required for specific parenting activities or training) (17). There were insufficient studies to warrant using all of these categories, so categories used were: no, indirect, and direct parental involvement. Other individual components included study design, primary setting, program length, sample size, target age, stage of cancer treatment, cancer diagnosis, behavioral theories used in program development, and outcome measures. Few studies reported effect sizes and summary measures varied widely across studies, so results were kept general. Risk of bias was assessed by documenting methodological quality parameters for included studies (Supplementary Table S2 online) (65).

Statement of Financial Support

This research was supported by the University of Texas MD Anderson Children’s Cancer Hospital ON (Optimizing Nutrition) to Life Program in the form of funding from the Gerber Foundation to J.C., a grant from the Children’s Art Project to J.C., support from the Annual Santa’s Elves Fundraiser held by the M.D. Anderson Advance Team, and philanthropic donations from Mr. David Herr and family, and from the Archer Foundation (San Angelo, Texas). Support from the National Institutes of Health through The University of Texas MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (CA 016672) is gratefully acknowledged. This research was made possible in part by institutional support from the US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (Cooperative Agreement 58-6250-0-008). M.C.S. was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant R25T (CA057730), Shine Chang, Ph.D., Principal Investigator; the Center for Energy Balance in Cancer Prevention and Survivorship, Duncan Family Institute. M.C.S. is currently being supported by the Comparative Effectiveness Research on Cancer in Texas from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP140020). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Agriculture.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

References

DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:252–71.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al.; Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Obesity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1359–65.

Garmey EG, Liu Q, Sklar CA, et al. Longitudinal changes in obesity and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4639–45.

Cohen J, Wakefield CE, Fleming CA, Gawthorne R, Tapsell LC, Cohn RJ. Dietary intake after treatment in child cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;58:752–7.

Badr H, Paxton RJ, Ater JL, Urbauer D, Demark-Wahnefried W. Health behaviors and weight status of childhood cancer survivors and their parents: similarities and opportunities for joint interventions. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:1917–23.

Green DM, Cox CL, Zhu L, et al. Risk factors for obesity in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:246–55.

Dickerman JD. The late effects of childhood cancer therapy. Pediatrics 2007;119:554–68.

Diller L, Chow EJ, Gurney JG, et al. Chronic disease in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort: a review of published findings. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2339–55.

Stolley MR, Restrepo J, Sharp LK. Diet and physical activity in childhood cancer survivors: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med 2010;39:232–49.

Badr H, Chandra J, Paxton RJ, et al. Health-related quality of life, lifestyle behaviors, and intervention preferences of survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:523–34.

Rabin C, Politi M. Need for health behavior interventions for young adult cancer survivors. Am J Health Behav 2010;34:70–6.

Ventura AK, Birch LL. Does parenting affect children’s eating and weight status? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5:15.

Mitchell GL, Farrow C, Haycraft E, Meyer C. Parental influences on children’s eating behaviour and characteristics of successful parent-focussed interventions. Appetite 2013;60:85–94.

Sleddens EF, Kremers SP, Hughes SO, et al. Physical activity parenting: a systematic review of questionnaires and their associations with child activity levels. Obes Rev 2012;13:1015–33.

Ohri-Vachaspati P, DeLia D, DeWeese RS, Crespo NC, Todd M, Yedidia MJ. The relative contribution of layers of the Social Ecological Model to childhood obesity. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:2055–66.

Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context - an integrative model. Psychol Bull 1993;113:487–496.

Hingle MD, O’Connor TM, Dave JM, Baranowski T. Parental involvement in interventions to improve child dietary intake: a systematic review. Prev Med 2010;51:103–11.

O’Connor TM, Jago R, Baranowski T. Engaging parents to increase youth physical activity a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:141–9.

Niemeier BS, Hektner JM, Enger KB. Parent participation in weight-related health interventions for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2012;55:3–13.

Epstein LH. Family-based behavioural intervention for obese children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1996;20 Suppl 1:S14–21.

Chamorro-Viña C, Ruiz JR, Santana-Sosa E, et al. Exercise during hematopoietic stem cell transplant hospitalization in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:1045–53.

Wurz A, Chamorro-Vina C, Guilcher GM, Schulte F, Culos-Reed SN. The feasibility and benefits of a 12-week yoga intervention for pediatric cancer out-patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:1828–34.

Järvelä LS, Kemppainen J, Niinikoski H, et al. Effects of a home-based exercise program on metabolic risk factors and fitness in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;59:155–60.

Järvelä LS, Niinikoski H, Heinonen OJ, Lähteenmäki PM, Arola M, Kemppainen J. Endothelial function in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: effects of a home-based exercise program. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1546–51.

Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY, Chiu SY, Lopez V. Effectiveness of an integrated adventure-based training and health education program in promoting regular physical activity among childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncol 2013;22:2601–10.

Chung OKJ, Li HCW, Chiu SY, Ho KY, Lopez V. Sustainability of an Integrated Adventure-Based Training and Health Education program to enhance quality of life among chinese childhood cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs 2014;38.5:366–74.

Müller C, Winter C, Boos J, et al. Effects of an exercise intervention on bone mass in pediatric bone tumor patients. Int J Sports Med 2014;35:696–703.

Perondi MB, Gualano B, Artioli GG, et al. Effects of a combined aerobic and strength training program in youth patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Sports Sci Med 2012;11:387–92.

Rosenhagen A, Bernhörster M, Vogt L, et al. Implementation of structured physical activity in the pediatric stem cell transplantation. Klin Padiatr 2011;223:147–51.

Sharkey AM, Carey AB, Heise CT, Barber G. Cardiac rehabilitation after cancer therapy in children and young adults. Am J Cardiol 1993;71:1488–90.

Shore S, Shepard RJ. Immune responses to exercise in children treated for cancer. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1999;39:240–3.

Winter CC, Müller C, Hardes J, Gosheger G, Boos J, Rosenbaum D. The effect of individualized exercise interventions during treatment in pediatric patients with a malignant bone tumor. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:1629–36.

Hudson MM, Tyc VL, Srivastava DK, et al. Multi-component behavioral intervention to promote health protective behaviors in childhood cancer survivors: the protect study. Med Pediatr Oncol 2002;39:2–1; discussion 2.

Cox CL, McLaughlin RA, Rai SN, Steen BD, Hudson MM. Adolescent survivors: a secondary analysis of a clinical trial targeting behavior change. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;45:144–54.

Gohar SF, Comito M, Price J, Marchese V. Feasibility and parent satisfaction of a physical therapy intervention program for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the first 6 months of medical treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;56:799–804.

Marchese VG, Chiarello LA, Lange BJ. Effects of physical therapy intervention for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004;42:127–33.

Keats MR, Culos-Reed N. A theory-driven approach to encourage physical activity in pediatric cancer survivors: a pilot study. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2009;31:267–83.

Keats MR, Culos-Reed SN. A community-based physical activity program for adolescents with cancer (project TREK): program feasibility and preliminary findings. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2008;30:272–80.

Huang JS, Dillon L, Terrones L, et al. Fit4Life: a weight loss intervention for children who have survived childhood leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:894–900.

Hartman A, te Winkel ML, van Beek RD, et al. A randomized trial investigating an exercise program to prevent reduction of bone mineral density and impairment of motor performance during treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:64–71.

Moyer-Mileur LJ, Ransdell L, Bruggers CS. Fitness of children with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia during maintenance therapy: response to a home-based exercise and nutrition program. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2009;31:259–66.

Rakhshani N, Jeffery AS, Schulte F, Barrera M, Atenafu EG, Hamilton JK. Evaluation of a comprehensive care clinic model for children with brain tumor and risk for hypothalamic obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1768–74.

San Juan AF, Chamorro-Viña C, Moral S, et al. Benefits of intrahospital exercise training after pediatric bone marrow transplantation. Int J Sports Med 2008;29:439–46.

San Juan AF, Fleck SJ, Chamorro-Viña C, et al. Effects of an intrahospital exercise program intervention for children with leukemia. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:13–21.

Ruiz JR, Fleck SJ, Vingren JL, et al. Preliminary findings of a 4-month intrahospital exercise training intervention on IGFs and IGFBPs in children with leukemia. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:1292–7.

Takken T, van der Torre P, Zwerink M, et al. Development, feasibility and efficacy of a community-based exercise training program in pediatric cancer survivors. Psychooncol 2009;18:440–8.

Esbenshade AJ, Friedman DL, Smith WA, et al. Feasibility and initial effectiveness of home exercise during maintenance therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Phys Ther 2014;26:301–7.

Yeh CH, Man Wai JP, Lin US, Chiang YC. A pilot study to examine the feasibility and effects of a home-based aerobic program on reducing fatigue in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Nurs 2011;34:3–12.

Tanir MK, Kuguoglu S. Impact of exercise on lower activity levels in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized controlled trial from Turkey. Rehabil Nurs 2013;38:48–59.

Donze J, Tercyak K. The survivor health and resilience education (SHARE) program: Development and evaluation of a health behavior intervention for adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2006;13:169–176.

Mays D, Black JD, Mosher RB, Heinly A, Shad AT, Tercyak KP. Efficacy of the Survivor Health and Resilience Education (SHARE) program to improve bone health behaviors among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Behav Med 2011;42:91–8.

Demark-Wahnefried W, Werner C, Clipp EC, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer and their guardians. Cancer 2005;103:2171–80.

Gruber KJ, Haldeman LA. Using the family to combat childhood and adult obesity. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6:A106.

Long KA, Marsland AL. Family adjustment to childhood cancer: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2011;14:57–88.

Kinahan KE, Sharp LK, Arntson P, Galvin K, Grill L, Didwania A. Adult survivors of childhood cancer and their parents: experiences with survivorship and long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2008;30:651–8.

Williams LK, Lamb KE, McCarthy MC. Parenting Behaviors and Nutrition in Children with Leukemia. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2015;22:279–90.

Hullmann SE, Wolfe-Christensen C, Meyer WH, McNall-Knapp RY, Mullins LL. The relationship between parental overprotection and health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer: the mediating role of perceived child vulnerability. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1373–80.

Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Butow P, Lenthen K, Cohn RJ. Parental adjustment to the completion of their child’s cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;56:524–31.

Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Adjustment and coping by parents of children with cancer: a review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 1997;5:466–84.

Vrijmoet-Wiersma CM, Kolk AM, Grootenhuis MA, et al. Child and parental adaptation to pediatric stem cell transplantation. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:707–14.

Colletti CJ, Wolfe-Christensen C, Carpentier MY, et al. The relationship of parental overprotection, perceived vulnerability, and parenting stress to behavioral, emotional, and social adjustment in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;51:269–74.

Fedele DA, Mullins LL, Wolfe-Christensen C, Carpentier MY. Longitudinal assessment of maternal parenting capacity variables and child adjustment outcomes in pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;33:199–202.

Wolfe-Christensen C, Mullins L, Fedele D, Rambo P, Eddington A, Carpentier M. The relation of caregiver demand to adjustment outcomes in children with cancer: the moderating role of parenting stress. Childrens Health Care 2010;39:108–24.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG ; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9, W64.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al.; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928.

Acknowledgements

We thank Helena Vonville, MLS MPH, and Amy Sisson, MLS MS for their guidance and verification of our search strategies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Tables

(PDF 22 kb)

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raber, M., Swartz, M., Santa Maria, D. et al. Parental involvement in exercise and diet interventions for childhood cancer survivors: a systematic review. Pediatr Res 80, 338–346 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2016.84

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2016.84

This article is cited by

-

Parent perceptions of their child’s and their own physical activity after treatment for childhood cancer

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Meal planning values impacted by the cancer experience in families with school-aged survivors—a qualitative exploration and recommendations for intervention development

Supportive Care in Cancer (2020)

-

Diet and exercise interventions for pediatric cancer patients during therapy: tipping the scales for better outcomes

Pediatric Research (2018)

-

Early Nutrition and Physical Activity Interventions in Childhood Cancer Survivors

Current Obesity Reports (2017)