Abstract

Purpose To evaluate the quality of life in glaucomatous patients using two different questionnaires: the medical outcomes study 36-item short-form health survey (MOS SF-36) and Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire and to compare these two questionnaires.

Methods Seventy-seven patients with glaucoma were consecutively selected. Two force-choice questionnaires were administered to each patient. Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was related to visual disability and the second was related to the quality of life from the MOS 36-item short-form health survey. Both questionnaires were evaluated among all the considered patients and the results were compared. Then the questionnaire which did the best evaluation was used to test the quality of life in three different subgroups based on the mean deviation of the worse eye. Mann–Whitney non parametric test and Spearman’s r coefficient were used and a P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. A linear regression model was used.

Results In the entire group (n = 77) the Mean Deviation (MD) was −6.5 ± 6.8 dB (mean ± standard deviation) and Corrected Pattern Standard Deviation (CPSD) was 4.7 ± 4.1 dB. The score of the Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was 8.3 ± 2.4, while MOS SF-36 score ranged from 60.5% to 100% (mean score %). A significant (P < 0.0001) correlation was found between the score of the Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire and MD (r = 0.79), Pattern Standard Deviation (PSD) (r = −0.68) and CPSD (r = −0.61).

Conclusion Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was more useful than MOS SF-36, both for the score and for the velocity to use. Furthermore Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was more significantly correlated to visual field MD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quality of life is an outcome measure which is hard to quantify by the physicians, however, for patients, it is very important. Each patient should be asked his own perceptions on his present status and on the course, as well as asked to describe his difficulties with daily tasks.

Glaucoma affects daily life both through visual deterioration and by the glaucoma treatment itself and the evaluation of glaucomatous patients’ disabilities is a difficult task. Because glaucoma is the third most common cause of blindness in the world and has been projected to become the most common cause of blindness in the first years of this millennium, it is important to know the quality of life of these patients.1,2

Glaucoma patients can lose quality of life (QoL) for several reasons: the diagnosis itself, the functional loss, the inconvenience of the treatment, the side effects of the treatment and the cost of the treatment.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the quality of life in patients with glaucoma using two different questionnaires: the medical outcomes study (MOS) 36-item short-form (SF-36) health survey (MOS SF-36) and Mills and Drance’s corrected questionnaire or Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire3,4,5,6 and to compare them.

Patients and methods

Seventy-seven patients with glaucoma were consecutively selected among 100 patients of the glaucoma unit of the University Eye Clinic of Genoa from September 1999 to November 1999. No informed consent was asked of patients who agreed to participate to the study. Twenty-three patients did not want to participate in the study or were excluded due to the inclusion criteria of the study.

Subjects were not excluded on the basis of age, gender, race and refractive error, but they were excluded if other ocular diseases were present (eg age-related macular degeneration, anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, etc). Previous eye surgery was not considered. Patients were considered to have primary open-angle glaucoma when they had a typical glaucomatous visual field and/or a typical abnormal optic nerve head/retinal nerve fibre layer (as described below), open angle on gonioscopy and no clinically apparent secondary cause for their glaucoma.7 One single observer (MI) judged whether patients had typical glaucomatous field and/or optic disc.

The abnormal optic nerve head/retinal nerve fibre layer classification was based on the presence of an optic rim notch or diffuse/generalised loss of optic rim tissue, vertical cup/disc diameter ratio asymmetry unexplained by side differences in optic disc size, disc haemorrhage, subjectively ascertained localised defect within the RNFL.8

All the patients had already had at least three visual field examinations in the last 3 years. A visual field examination by the Humphrey Field Analyser (HFA), program 30–2 standard SITA, was performed on all the patients. Only reliable fields were used, as determined by the reliability parameters: there had to be less than three fixation losses, and false-positive and false-negative responses both had to be less than 10%.

A visual field was classified as glaucomatous if it had: (a) three adjacent points down by 5 dB with one of the points being down by at least 10 dB; (b) two adjacent points down by 10 dB; or (c) a 10 dB difference across the nasal horizontal meridian in at least two adjacent points. None of the points could be edge points except immediately above or below the nasal horizontal meridian.8,9 Mean deviation (MD), pattern standard deviation (PSD) and corrected pattern standard deviation (CPSD) were considered. Patients were excluded from the study if the difference between the two eyes was greater than 4 dB both for the MD and for CPSD.

Although some authors have shown that binocular sensitivity is more accurately modelled than monocular sensitivity, in this study we tried to evaluate patient’s quality of life just by using the simple monocular visual field.10,11 Thus visual field indices of the worse eye were considered for statistical purpose.

Two force-choice questionnaires were administered to each patient (Tables 1 and 2). Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was related to visual disability derived from those answers in a previous study (Mills, Drance),3,4 the second was related to the quality of life from the SF-36.5,6 The former was mainly used to evaluate the capacity to detect quality of vision of the patients,3,4 while the latter questionnaire was introduced to assess different aspects of patient’s health: (1) limitations in physical activities; (2) limitations in social activities because of physical and emotional problems; (3) limitations in usual role activities; (4) bodily pain; (5) general mental health; (6) limitations in usual role activities because of emotional problems; (7) vitality; (8) general health perceptions.5,6 The questionnaires were written in Italian language and given to the patients, who read and answered them on their own. Sometimes to be quicker, a physician (MI) helped the patients to fill in the questionnaire.

Then the questionnaire which had the best evaluation, was used to test the quality of life in three different subgroups based on the visual field of the worse eye. Thus the entire group was divided into three subgroups: the early glaucoma group (MD > −6 dB), the moderate glaucoma group (−6 ≥ MD ≥ −12 dB) and the advanced glaucoma group (MD < −12 dB).7

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad StatMate™ (version 1.00, San Diego, CA, USA) for Windows (Version 6.0, Microsoft Corporation). All the data were analysed by a descriptive analysis. Student’s t-test and Pearson’s r coefficient of correlation were used when the distribution of the data was normal, the Mann–Whitney non parametric test and Spearman’s r coefficient were used instead, when the distribution of data was not normal. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. A linear regression model was used to determine the independent contribution of variables included in the model.

Results

In the entire group (n = 77), the mean deviation was −6.5 ± 6.75 dB (mean ± standard deviation) ranging from −23.12 dB to 1.2 dB, PSD was 4.46 ± 4.24 dB ranging from 0.42 to 17.4 dB and CPSD was 4.68 ± 4.09 dB ranging from 0.38 to 17.3 dB. Furthermore the mean age was 62.4 ± 8.3 years, the refractive error was −1.75 ± 1.25 diopters ranging from −6.5 to 4.5 D and the visual acuity ranged from 20/20 to 20/50.

The score of the Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was 8.34 ± 2.37 and Table 3 listed the results of the entire group, while the SF-36 score ranged from 60.5% to 100% (mean score %).

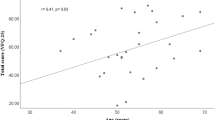

A significant (P < 0.0001) correlation was found between the score of the Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire and MD (r = 0.79), PSD (r = −0.68) and CPSD (r = −0.61), while no significant correlation was found with age. A significant (P < 0.05) correlation was also found between the SF-36 score and age (r = −0.36), MD (r = 0.40), PSD (r = −0.34) and CPSD (r = −0.32). A linear regression model was used to evaluate which variable was the most important predictive: for the Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire score, MD was the most important predictive variable, while age was the most important predictive variable for the SF36 score, followed by MD.

Because of the least significant correlation between SF-36 scores and visual field indices (MD and CPSD) and the correlation between SF-36 and age, only Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was divided into the three subgroups based on the visual field damage.

When the entire group was divided into three subgroups: in the group with early glaucoma (n = 40) the mean age was 62 ± 8.9 years, mean deviation was −1.62 ± 1.9 dB (mean ± standard deviation), PSD was 2.26 ± 1.25 dB, CPSD was 2.09 ± 1.32 dB and the mean score was 9.59 ± 1.02. In the group with moderate glaucoma (n = 19) the mean age was 60.8 ± 9.2 years, mean deviation was −7.18 ± 0.94 dB (mean ± standard deviation), PSD was 3.7 ± 1.17 dB, CPSD was 3.55 ± 1.33 dB and the mean score was 7.65 ± 2.74. In the group with advanced glaucoma (n = 18), the mean age was 64.9 ± 5.1 years, mean deviation was −17.69 ± 3.52 dB (mean ± standard deviation), PSD was 11.7 ± 2.42 dB, CPSD was 11.86 ± 2.45 dB and the mean score was 6.06 ± 2.39. Table 3 lists the results of the three subgroups. Furthermore the score value obtained in the early glaucoma group was significantly different from the score of moderate (P < 0.01) and advanced glaucoma (P < 0.001) and a significant difference was found between the moderate glaucoma group score and the advanced glaucoma group score (P < 0.05).

The questions: ‘Do you notice variations in colour intensity?, Do you bump into things sometimes?, Do you trip on things or have difficulty with stairs?, Do you have difficulty finding things that you have dropped?’ had the highest score (Table 3), in particular in patients with a MD < −12 dB. When the visual field of patients with high score for the following questions: ‘Do you ever notice that parts of your field of vision are missing?, Have you noticed any deterioration in your sight over the last few years? and Do you ever have trouble following a line of print or finding the next line when reading?’ was checked, in 60.1% of the patients a paracentral scotoma was shown.

Discussion

The term ‘quality-adjusted vision years’ was introduced to focus on the main goal, that is, maintenance of useful vision for daily life. QoL can be measured by questionnaire but it is also dependent on subjective evaluation by the patient. Many factors can be related to patient’s quality of life: visual disability, problems with taking medication, incompatibility of treatment with working hours, daily life requirements, general side effects due to medication, local side effects, incompatibility of treatment with physical or mental situation.

These considerations have to be made for each individual, taking into account his visual field disturbance (especially binocular), reduced visual acuity due to glaucoma or treatment, and visual disturbance due to other factors that can be treated, such as cataract and judgement of visual disturbance during night and dim light.

In the long term, the life expectancy of the individual is the main factor when considering whether treatment is needed. In young glaucomatous patients the main goal must be to maintain life long vision and it is more difficult than in older glaucomatous patients.

The main challenge for the glaucoma specialist is to guide the patients according to their therapeutic needs while at the same time maintaining their confidence in the goal of life-long acceptable levels of visual quality.

In 1984 Ross et al, comparing a group of visual function tests, including near visual field, contrast sensitivity, and superimposed monocular kinetic visual field, in a 84-item questionnaire, found that the psychophysical tests were the best predictors of perceived disability.12 Mills and Drance using a 15-item questionnaire found that the four most important questions were: (1) Do you have trouble following a line of print or finding the next line?, (2) Do you bump into things?, (3) Have you had to give up any activities because of your vision?, (4) Do you notice any variation in colour richness from time to time?3 Using the SF-36, Parrish et al found that the scores of patients with glaucoma were comparable with subjects without severe systemic medical problems.13 Using a revised Mills and Drance’s questionnaire, Viswanathan et al found strong correlation between some types of perceived visual disability and the severity of binocular field loss.4

The results of this study showed that the revised Mills and Drance’s questionnaire or Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was the most sensitive one in glaucomatous patients. The presence of significant differences in the questionnaire score among the three subgroups of patients based on the stage of the disease suggested its utility for clinical purposes. Indeed all patients should be tested with this questionnaire to evaluate whether the treatment or emotional limitations can influence the QoL of each patient. As in previous studies, the following questions: ‘Do you notice variations in colour intensity?, Do you bump into things sometimes?, Do you trip on things or have difficulty with stairs?, Do you have difficulty finding things that you have dropped?’ were the most useful questions to evaluate patients’ limitations due to glaucomatous damage. Furthermore a positive answer to these questions: ‘Do you ever notice that parts of your field of vision are missing?, Have you noticed any deterioration in your sight over the last few years? and Do you ever have trouble following a line of print or finding the next line when reading?’ was mainly given by patients with paracentral scotoma.

Although a decrease in SF-36 score was found in patients with the lowest MD values and a mild correlation with visual field indices, SF-36 did not succeed in outlining the functional deficit of the patient, but it was able to give more information on emotional and social limitations. Furthermore the mild correlation with age suggested the possibility that the decrease in score was also due to the patient’s age. The correlation between SF-36 questionnaire and age could be also due to the type of questionnaire: SF-36 tries to assess different aspects of patient’s health and probably older patients had more health problems than younger ones. This correlation was not present when Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire was used.

The main difference of this study from the previous ones was that the worse visual field test was considered and the simultaneous binocular test was not used.14 Esterman binocular disability score is usually used because patients with glaucoma can have monocular disease or asymmetric damage, however, in this study, patients with similar binocular disease were considered and we tried to use a different approach. For that reason we preferred to use visual field indices rather than the Esterman score. Using the monocular visual field, some time can be saved but this technique can make you lose some information on the binocular visual field contribution.

Due to the complexity of the SF-36, a simpler and more direct questionnaire could be sufficient to test quality of life and vision in patients with glaucoma. Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire had also similar questions to the SF-36, such as numbers 1, 2 and 7. Furthermore although some details can be lost to assess the quality of life by just using the monocular visual field, in this study we found that monocular visual field was significantly correlated to the questionnaire scores.

The SF-36 is a global quality of life measure and because the early stage of glaucoma does not produce symptoms, it is not surprising that this scale was not so useful as the other. However it is important to remember that even patients with early glaucoma can have emotional problems that should be tested.

The main challenge for the glaucoma specialist is to guide the patients according to their therapeutic needs while at the same time maintaining their confidence in the goal of life-long acceptable levels of visual quality. Therefore, quality of life depends on psychological training for the glaucoma patient and the physician’s capacity not to frighten the patient with the prospect of blindness if their compliance to treatment is good. To save visual field by treatment is fundamental in the glaucoma follow-up but to improve quality of life could be more important for the patient. Using the revised Viswanathan et al’s questionnaire, the physician could know more about the QoL of each single patient in a short time and try to improve it.

References

Foster A, Johnson GJ . Magnitude and cause of blindness in the developing world. Int Ophthalmol 1999; 14: 135–140

Quigley HA . Number of people with glaucoma world-wide. Br J Ophthalmol 1996; 80: 389–393

Viswanathan AC, McNaught AI, Poinoosawmy D et al. Severity and stability of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117: 450–454

Mills RP, Drance SM . Estermann disability rating in severe glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1986; 93: 371–378

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD . The MOS 36-item short-form healthy survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE . The MOS 36-item short-form healthy survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 1993; 31: 247–263

European Glaucoma Society. 1998 Terminology and guidelines for glaucoma Dogma, Savona, Italy 1998

Iester M, Mikelberg FS . Optic nerve head morphology in high tension and normal tension glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117: 1010–1013

Caprioli J . The contour of the juxtapapillary nerve fiber layer in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1990; 97: 358–366

Crabb DP, Viswanatha AC, McNaught AI, Poinoosawmy D, Fitzke FW, Hitchings RA . Simulating binocular field status in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82: 1236–1241

Nelson-Quigg JM, Cello K, Johnson CA . Predicting binocular visal field sensitivity from monocular visual field results. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000; 41: 2212–2221

Ross JE, Bron AJ, Clarke DD . Contrast sensitivity and visual disability in chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1984; 68: 821–827

Parrish RK, Gedde SJ, Scott IU et al. Visual function and quality of life among patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115: 1447–1455

Estermann B . Functional scoring of the binocular field. Ophthalmology 1982; 89: 1226–1234

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iester, M., Zingirian, M. Quality of life in patients with early, moderate and advanced glaucoma. Eye 16, 44–49 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700036

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700036

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Veränderungen der Lebensqualität von Glaukompatienten über einen Zeitraum von 8 Jahren

Die Ophthalmologie (2022)

-

Using eye movements to detect visual field loss: a pragmatic assessment using simulated scotoma

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Vision-related quality of life and symptom perception change over time in newly-diagnosed primary open angle glaucoma patients

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Quality of Life in Glaucoma: A Review of the Literature

Advances in Therapy (2016)

-

Comparing the effectiveness of selective laser trabeculoplasty with topical medication as initial treatment (the Glaucoma Initial Treatment Study): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial

Trials (2015)