Key Points

-

Carers of patients with dementia worry about taking the person they care for to the dentist.

-

Patients with even an advanced dementia may be able to co-operate with dental care as appropriate behaviours are often learned in childhood, and these distant memories may be retained.

-

Patients with dementia may be unable to verbally express physical discomfort, making dental examinations even more important.

Abstract

Objective To ascertain the views of carers of patients with dementia, on the patient's dental health needs.

Design Prospective survey using semi-structured interview.

Setting Dementia day care unit for patients living in their own homes.

Subjects and method Twenty-eight carers of dementia sufferers were interviewed between March and September 2000, as part of regular clinical reviews of patient's needs. Carers' views on the dental care needs of patients were ascertained. Cognitive and behavioural assessments of patients were also made using the Clifton Assessment Procedure for the Elderly (CAPE).

Main outcome measure Dental unmet need ie the carer deciding that the patient needed a dental examination, but anticipating that this would be problematic, the carer would not take them.

Results Twenty one per cent met criteria for dental unmet need.

Conclusions Carers of people with dementia may be reluctant to take those they care for to the dentist. We need to explore ways to ensure appropriate dental surgery attendance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It is considered important in dementia care to maximize patients' well being in all domains, by attending to their physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs. The generally accepted gold standard of care for routine dental check-ups is six monthly. There is the potential that neglect of dental care may lead to tooth decay, pain, inflammation, all of which may make the patient more confused. Having both teeth and dementia in context of advancing age is a new problem. In previous generations people were more likely to have been edentulous in old age.

There is little literature on dental care in dementia. One study of caregiver's perspectives on the provision of dental care for cognitively impaired older adults had only a 14% response rate from a postal questionnaire.1 A literature review on the care of patients with Alzheimer's disease who attend the dental surgery, largely focused on medication, sedation and communication but not the reasons which prevent people attending.2

In 1992, only 30% of adults over 75 years of age were registered with a dentist compared with 61% of all adults.3 An interview study of 263 housebound adults (over 60 years of age) found that only 17% had attended a dentist in the previous year, and only 37% had attended in the previous four years. Ninety-three per cent only attended when they had problems. Ninety-three per cent of carers reported having difficulty when trying to obtain care, but the nature of the difficulty was not defined.4

Even in an advanced dementia, there is frequently relative preservation of memories from the distant past. A Swedish study of patients (age range 73–100) with fairly advanced Alzheimer's disease suggested that dental co-operation was not directly related to degree of dementia because of preservation of remote memory and behaviours relating to dental experiences earlier in life.4

The Herga Day Unit in South Harrow cares for patients with moderate to severe dementia living in their own homes. Informal questioning of carers indicated that patients were not attending for dental checks at the usual recommended frequency. Since most of the patients are dependent on informal carers it was decided to interview carers about dental care needs.

Method

A semi-structured interview was used to ask the carers for their assessment of the patient's dental needs. Information requested included:

-

If the patient has teeth and/or dentures

-

If the dentures fit properly

-

When the patient was last seen by a dentist

-

If the carer thought review was needed, and

-

If they anticipated problem behaviour in taking the person to the dentist

Patients' gender and CAPE (Clifton Assessment Procedure for the Elderly) score5 were documented. The CAPE score is recorded every six months for all patients attending the day centre. The scale is well validated for measuring cognitive and behavioural function in older adults. 'E' indicates worst function, 'A' best function. Data were collected during routine six monthly reviews of patients' and carers' needs between March and September 2000.

Dental unmet need was defined as the carer deciding that the patient needed a dental examination, but anticipating that this would be problematic would not take them.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse data.

Results

All 28 carers agreed to participate in the study.

Most patients scored in the severe impairment range (75%, D and E) on the CAPE behavioural scale. Forty per cent scored D or E on the cognitive scale. This indicates considerable impairment and dependency in the group as a whole. Only one third of patients had had a dental review in the previous six months. There was a considerable degree of unmet need with one in five patients not having a dental check when it had been identified as necessary by the carers. Some patients with more advanced dementia visited the dentist without difficulty.

Carers gave various comments and suggestions. Two knew that their relatives had a life long fear of dentists and that it would be near impossible to take them to a dentist. One carer feared lack of co-operation both en route to and at the dentist. Another patient had been a prisoner of war, was fearful of any medical or dental procedures, had no teeth and no dentures and was reported to have pulled out his own teeth as he saw necessary.

Discussion

Limitations of this study were its small size and the lack of control group. The small size gives limitations in terms of statistical analysis and in interpretation of data. As a control group, spouse carers could have been asked the same questions which would have given a picture of level of dental care in a similar age population without dementia. However, anecdotal evidence leads us to suspect that carers may neglect their own needs and may not be representative of the whole population. However, rates of attending the dentist for our population with dementia do not appear too different from rates previously identified for older people, whether independent or dependent upon others.3,4

That one in five patients had not had a dental check when identified as necessary by the carers raises issues of the provision of dental care for this group of people. It may be best provided at the day unit, in an environment known to the patient and easily accessible, by the community dental service or by a dentist previously known to the patient. Nordenram et al.6 devised a dental behaviour index (DBI, summarised in Table 2) which was useful in predicting cognitive response to dental treatment. It may be that the DBI could be used either in the surgery or in picture form at the day unit for a preliminary assessment of the patient's likely ability to respond appropriately to dental care, and thus guide the carer and dentist accordingly. This needs further investigation.

This study can probably best be regarded as a pilot for a larger, prospective study of dental care in dementia. With more comprehensive assessments of cognitive function and behaviour, and actual dental assessments, further research would aim to provide practical recommendations to improve dental care for those with dementia.

References

Blanco V L, Levy S M, Ettinger R L, Logan H, Buckwalter K C . Challenges in geriatric oral health research methodology concerning care givers of cognitively impaired elderly adults. Special Care Dent 1997; 17: 129– 132.

Henry R G . Neurological disorders in dentistry: managing patients with Alzheimer's disease J Indiana Dent Assoc 1997-8; 76: 51– 57.

Annual Report of the Dental Practice Board 1991-2. Eastbourne Dental Practice Board, (August 1992), quoted in ref 4

Lester V, Ashley F P, Gibbons D E . Reported dental attendance and perceived barriers to care in frail and functionally dependent older adults. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 285– 289

Pattie A H, Gilleard C J . Manual of the Clifton Assessment procedures for the Elderly (CAPE) Sevenoaks: Hodder and Stoughton Educational, 1979.

Nordenram G, Ryd-kjellen E, Ericsson K, Winblad B . Dental management of Alzheimer patients. A predictive test of dental co-operation in individualised treatment planning. Acta Odontol Scand 1997; 55: 148– 154.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks all the carers who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hilton, C., Simons, B. Dental surgery attendance amongst patients with moderately advanced dementia attending a day unit: a survey of carers' views. Br Dent J 195, 39–40 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4810277

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4810277

This article is cited by

-

Dementia friendly dentistry for the periodontal patient. Part 2: ethical treatment planning and management

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Utilization of dental care among patients with severe mental illness: a study of a National Health Insurance database

BMC Oral Health (2016)

-

Forget me not – the role of the general dental practitioner in dementia awareness

British Dental Journal (2014)

-

Access to special care dentistry, part 4. Education

British Dental Journal (2008)

-

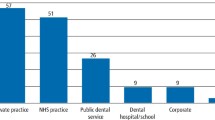

Dental attendance of patients with dementia

British Dental Journal (2003)