Abstract

Background

Our aim was to compare pediatric infective endocarditis (IE) with the clinical profile and outcomes of IE in adults.

Methods

Prospective multicenter registry in 31 Spanish hospitals including all patients with a diagnosis of IE from 2008 to 2020.

Results

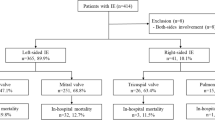

A total of 5590 patients were included, 49 were <18 years (0.1%). Congenital heart disease (CHD) was present in 31 children and adolescents (63.2%). Right-sided location was more common in children/adolescents than in adults (46.9% vs. 6.3%, P < 0.001). Pediatric pulmonary IE was more frequent in patients with CHD (48.4%) than in those without (5.6%), P = 0.004. Staphylococcus aureus etiology tended to be more common in pediatric patients (32.7%) than in adults (22.3%), P = 0.082. Heart failure was less common in pediatric patients than in adults, due to the lower rate of heart failure in children/adolescents with CHD (9.6%) with respect to those without CHD (44.4%), P = 0.005. Inhospital mortality was high in both children, and adolescents and adults (16.3% vs. 25.9%; P = 0.126).

Conclusions

Most IE cases in children and adolescents are seen in patients with CHD that have a more common right-sided location and a lower prevalence of heart failure than patients without CHD. IE in children and adolescents without CHD has a more similar profile to IE in adults.

Impact

-

Infective endocarditis (IE) in children and adolescents is often seen in patients with congenital heart disease (CHD).

-

Right-sided location is the most common in patients with CHD and heart failure is less common as a complication compared with patients without CHD.

-

Infective endocarditis (IE) in children/adolescents without CHD has a more similar profile to IE in adults.

-

In children/adolescents without CHD, locations were similar to adults, including a predominance of left-sided IE.

-

Acute heart failure was the most frequent complication, seen mainly in adults, and in children/adolescents without CHD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a serious condition that carries high morbidity and mortality.1,2 Recent changes in the epidemiology of IE are mainly related to population aging and the greater frequency of risk factors. These risk factors include cardiac surgeries, implantable cardiac devices (pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators), percutaneous treatment of structural heart diseases, and other healthcare-associated procedures.3 IE is uncommon in children,4 although due to the progressive greater survival of children with congenital heart disease (CHD), its frequency is increasing.5,6,7 Most previous studies that analyze the peculiarities of pediatric IE do not compare their clinical profile and evolution with adult IE.8,9,10,11,12,13 In addition, there have been recent changes in the antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations for IE.14 Children/adolescents and adults have differences in comorbidities and predisposing factors for IE that could lead to differences in etiology, diagnosis, and prognosis.

The aim of our work is to determine the clinical profile, risk factors, mode of presentation, and outcome of pediatric IE, and to compare it to adult IE. We have also analyzed IE in patients with and without CHD.

Methods

Prospective multicentre registry in 31 Spanish hospitals “Spanish Collaboration on Endocarditis—Grupo de Apoyo al Manejo de la Endocarditis infecciosa en ESpaña (GAMES)”.15,16,17 All patients with a definite or possible diagnosis of IE were included from January 2008 to December 2020. Patients were classified into 2 groups according to the age at presentation: pediatric group with children and adolescents (<18 years) and adult group (≥18 years). Comparative analysis was performed between both groups. Patients were also compared according to the history of CHD.

This study was accomplished with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the recruiting hospitals. All patients provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are shown as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile rank) for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Continuous quantitative variables were compared using the Student’s t-test and ANOVA for the comparison of means. Continuous variables

were compared using the Mann Whitney test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum in nonparametric data. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test and the Fischer exact test. The goodness of fit of the final multivariate model was assessed again by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Multivariate analysis included multiple logistic regression techniques and Cox regression modeling for the study endpoints. To determine which variables were entered into the final model, we used a sequential inclusion and exclusion method, with an inclusion P threshold lower than 0.05 and exclusion over 0.1. The final model included age, sex, type of valve, comorbidities and previous medical history, complications, and history of CHD. Kaplan–Meier survival curve free of mortality at 1 year was generated with log-rank test analysis and considering censored episodes according to the time measured for each endpoint. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM, SPSS Statistics., Chicago, IL).

Results

Demographic and comorbidities

During the study period, a total of 5590 patients with a diagnosis of IE were included in the GAMES registry. Forty-nine (0.9%) were <18 years, and 5541 (99.1%) were adults. Table 1 shows baseline, demographic, and clinical characteristics according to age group. Compared to the adult group, pediatric patients had a lower proportion of males, cardiovascular risk factors, and age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index.

Location and etiology

Right-sided location was common in the pediatric group and pulmonary valve location was present in one-third of children/adolescents. Left-sided location was common in adults with involvement of the aortic valve in 52% of those ≥18 years. Pacemaker/implantable cardioverter defibrillator-related and poly-valvular IE were uncommon in children/adolescents (only 1 case each) compared to adults (10% and 14%, respectively). Overall, the frequency of prosthetic valve IE was similar in adults and children/adolescents (31.2% and 24.5%, respectively).

The most common identified microorganism was Staphylococcus aureus (33% in the pediatric group and 22% in adults). Gram-negative etiology was more frequent in children/adolescents than in adults (33% vs. 4%).

Complications, surgery, and outcome

Persistent bacteremia, sepsis, vascular phenomena, and new-onset murmurs were more common in the pediatric group than in the adult group (Table 2). We found a trend towards lower mortality in children compared to adults, which did not reach statistical significance in univariate analysis (Fig. 1) and in multivariate analysis (Table 3). Mortality risk was higher in patients who developed heart failure.

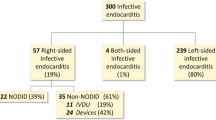

IE with and without CHD

A total of 31 pediatric patients (63.3%) and 31 adults (5.6%) had a history of CHD (Table 4). In pediatric patients without CHD, left-sided IE was more common, and the most frequent location was the mitral valve (56%). In children/adolescents with CHD, right-sided IE was more common, and the most frequent location was the pulmonary valve (48%). Comorbidities tended to be more frequent in children/adolescents without CHD. In children with CHD, prosthetic IE was common (36% prosthetic valve + 26% repair material). Heart failure and valve perforation were more common in children/adolescents without CHD than in those with CHD. CHD was not associated with differences in mortality (odds ratio [OR] 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.21–34.03, P = 0.457). Figure 2 shows the most frequent types of CHD; Tetralogy of Fallot was present in 7 patients (23.3%).

The most common location in adults with CHD was the left valves, especially the aortic valve (63%) (Table 5 and Supplementary Table & Figure). Adults with CHD were younger and had less comorbidity than adults without CHD. Heart failure and valve perforation were also more common in adults without CHD than in those with CHD. Mortality was significantly higher in adults without CHD than in those with CHD (32.9% vs. 12.9%), and adults without CHD also underwent cardiac surgery less often than adults with CHD (46% vs. 61%).

Discussion

We have found substantial differences in the clinical profile and mode of presentation of pediatric IE compared to adult IE. This was particularly evident for children/adolescents with CHD.

IE in children is very rare and represents a minority of all cases.18,19,20 About two-thirds of our pediatric patients had CHD, as previously reported.8,9,11,21,22,23 In fact, CHD is the predominant underlying condition for pediatric IE in developed countries.4 Most of our children/adolescents who did not have CHD presented other IE risk factors. The association of chronic conditions with non-CHD pediatric IE has also been found in previous studies.13,23

An increase in Staphylococcus aureus infections has been described,20 especially in healthcare-related IE cases.24 In children, both Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus spp. are frequent,9,12,13,21,22,23,25 although in recent years there has been an increase in streptococcal infections.8 We have found differences in the microbiological causative pathogens according to age and medical history. In children/adolescents, about 33% of cases of IE were caused by Staphylococcus aureus, while in adults this proportion was 22%. Furthermore, gram-negative bacilli were also common in children with CHD (25%). This high frequency of gram-negatives is noteworthy, since gram-negatives IE is rare, due to the difficulty of these microorganisms to adhere to the endothelium.26 It should be noted that Gram-negative bacillary bacteremia is a common cause of bacteremia in the community.27 Although some studies have estimated the rate of IE with negative cultures in 15–30% of cases,8,21 in our registry only a minority of the total patients had negative blood cultures (<10%). An improvement in microbiological diagnostic techniques in the last decade may have facilitated the isolation of microorganisms that cause IE.28

The risk of IE can vary widely among CHD lesions, and the highest risk has been observed among patients with cyanotic CHD.13,29 We have found that the most common CHD in children/adolescents with IE was the tetralogy of Fallot.13 Right-sided IE was very common in our pediatric patients with CHD, as half of them presented with pulmonary valve involvement. Pulmonary valve IE is extremely rare in patients with a normal structural heart,30 although its incidence is increasing in patients with complex CHD.11,31,32,33,34

Acute heart failure was the most frequent complication, seen mainly in adults, and children/adolescents without CHD. Heart failure is associated with mortality.35 A greater left-sided valve involvement could be the cause of the higher frequency of heart failure in patients without CHD, since right valve involvement usually has better hemodynamics and prognosis.36 Regarding treatment, more than half of our patients had an indication for surgical treatment, a proportion similar to that reported in the study by Shamszad et al.25 performed in patients <21 years.

The case fatality rate was similar in adults and children/adolescents. Pediatric patients presented a trend towards lower 12-month mortality but the rate of 20%, similar to that reported in a previous study21 is still a high one. Previous data suggest a relation of severe CHD or complex cardiac interventions,37 with higher mortality, but this was not the case in our cohort.

Compared to adults, we found that children/adolescents with IE and CHD have a different clinical profile and presentation. The differences with adults are probably more related to CHD itself than to age. It is foreseeable that the frequency of CHD-associated IE will rise in the near future5,20,37 so, further studies focused on this group of patients would be welcome. Patients with cyanotic CHD should be closely monitored and adequate antimicrobial prophylaxis should be performed in them, as they are at the highest risk of IE.

Adults with CHD were younger and had fewer comorbidities than those without CHD, as previously described.38,39 The most common etiology in adults with CHD was Streptococci, also described in previous reports.39,40 The greater aortic valve involvement in adults with CHD and IE was related to the type of underlying heart disease, since in adults with CHD bicuspid aortic valve disease was present in almost half of cases and in children/adolescents, it was tetralogy of Fallot in near one out of four patients.

This study has some limitations. The number of pediatric patients was small, as some GAMES centers do not have pediatric departments, and Children Hospitals are not included in GAMES. The inclusion of patients in the registry took more than a decade, so it is possible that there were some changes in the management of patients according to the recommendations and changes in the clinical practice guidelines.14,41

In conclusion, most IE cases in children and adolescents are seen in patients with CHD that have a more common right-sided location and a lower prevalence of heart failure compared with those without CHD. Pediatric IE without CHD has a similar profile to IE in adults.

References

Baddour, L. M. et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 132, 1435–1486 (2015).

Habib, G. et al. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: a prospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 40, 3222–3232 (2019).

Shah, A. S. V. et al. Incidence, microbiology, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with infective endocarditis. Circulation 141, 2067–2077 (2020).

Baltimore, R. S. et al. Infective endocarditis in childhood: 2015 update. Circulation 132, 1487–1515 (2015).

Zimmerman, M. S. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of congenital heart disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4, 185–200 (2020).

Sakai Bizmark, R., Chang, R.-K. R., Tsugawa, Y., Zangwill, K. M. & Kawachi, I. Impact of AHA’s 2007 guideline change on incidence of infective endocarditis in infants and children. Am. Heart J. 189, 110–119 (2017).

Ferrieri, P. et al. Unique features of infective endocarditis in childhood. Circulation 105, 2115–2126 (2002).

Gupta, S., Sakhuja, A., McGrath, E. & Asmar, B. Trends, microbiology, and outcomes of infective endocarditis in children during 2000-2010 in the United States. Congenit. Heart Dis. 12, 196–201 (2017).

Johnson, J. A., Boyce, T. G., Cetta, F., Steckelberg, J. M. & Johnson, J. N. Infective endocarditis in the pediatric patient: a 60-year single-institution review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 87, 629–635 (2012).

Martin, J. M., Neches, W. H. & Wald, E. R. Infective endocarditis: 35 years of experience at a children’s hospital. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24, 669–675 (1997).

Ahmadi, A. & Daryushi, H. Infective endocarditis in children: a 5 year experience from Al-Zahra Hospital, Isfahan, Iran. Adv. Biomed. Res 3, 228 (2014).

Tseng, W.-C. et al. Changing spectrum of infective endocarditis in children: a 30 years experiences from a tertiary care center in Taiwan. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 33, 467–471 (2014).

Day, M. D., Gauvreau, K., Shulman, S. & Newburger, J. W. Characteristics of children hospitalized with infective endocarditis. Circulation 119, 865–870 (2009).

Habib, G. et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 36, 3075–3128 (2015).

Armiñanzas, C. et al. Role of age and comorbidities in mortality of patients with infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 64, 63–71 (2019).

Vicent, L. et al. Prognostic implications of a negative echocardiography in patients with infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 52, 40–48 (2018).

Vicent, L., Saldivar, H. G., Muñoz, P., Bouza, E. & Martínez-Sellés, M. The role of echocardiography as a risk-stratification tool in infective endocarditis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 53, e23–e24 (2018).

Joffre, J. et al. Epidemiology of infective endocarditis in French intensive care units over the 1997-2014 period - from CUB-Réa Network. Crit. Care 23, 143 (2019).

Cahill, T. J. & Prendergast, B. D. Infective endocarditis. Lancet 387, 882–893 (2016).

Mahony, M. et al. Infective endocarditis in children in Queensland, Australia: epidemiology, clinical features and outcome. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 40, 617–622 (2021).

Luca, A.-C. et al. Difficulties in diagnosis and therapy of infective endocarditis in children and adolescents-cohort study. Healthcare 9, 760 (2021).

Cao, G.-F. & Bi, Q. Pediatric infective endocarditis and stroke: a 13-year single-center review. Pediatr. Neurol. 90, 56–60 (2019).

Lin, Y.-T., Hsieh, K.-S., Chen, Y.-S., Huang, I.-F. & Cheng, M.-F. Infective endocarditis in children without underlying heart disease. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 46, 121–128 (2013).

Selton-Suty, C. et al. Preeminence of Staphylococcus aureus in infective endocarditis: a 1-year population-based survey. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54, 1230–1239 (2012).

Shamszad, P., Khan, M. S., Rossano, J. W. & Fraser, C. D. J. Early surgical therapy of infective endocarditis in children: a 15-year experience. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 146, 506–511 (2013).

Morpeth, S. et al. Non-HACEK gram-negative bacillus endocarditis. Ann. Intern. Med. 147, 829–835 (2007).

Diekema, D. J. et al. Epidemiology and outcome of nosocomial and community-onset bloodstream infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 3655–3660 (2003).

Faraji, R. et al. The diagnosis of microorganism involved in infective endocarditis (IE) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and real-time PCR: a systematic review. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 34, 71–78 (2018).

Sun, L.-C. et al. Risk factors for infective endocarditis in children with congenital heart diseases—a nationwide population-based case control study. Int. J. Cardiol. 248, 126–130 (2017).

Prieto-Arévalo, R. et al. Pulmonary infective endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 2782–2784 (2019).

Egbe, A. C., Vallabhajosyula, S., Akintoye, E. & Connolly, H. M. Trends and outcomes of infective endocarditis in adults with tetralogy of fallot: a review of the National Inpatient Sample Database. Can. J. Cardiol. 35, 721–726 (2019).

Kelchtermans, J. et al. Clinical characteristics of infective endocarditis in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 38, 453–458 (2019).

Esposito, S. et al. Infective endocarditis in children in Italy from 2000 to 2015. Expert Rev. Antiinfect. Ther. 14, 353–358 (2016).

Dixon, G. & Christov, G. Infective endocarditis in children: an update. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 30, 257–267 (2017).

Thom, K. et al. Incidence of infective endocarditis and its thromboembolic complications in a pediatric population over 30years. Int. J. Cardiol. 252, 74–79 (2018).

Shmueli, H. et al. Right‐sided infective endocarditis 2020: challenges and updates in diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e017293 (2020).

Jortveit, J. et al. Endocarditis in children and adolescents with congenital heart defects: a Norwegian nationwide register-based cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child 103, 670–674 (2018).

Tutarel, O. et al. Infective endocarditis in adults with congenital heart disease remains a lethal disease. Heart 104, 161 (2018).

Mylotte, D. et al. Incidence, predictors, and mortality of infective endocarditis in adults with congenital heart disease without prosthetic valves. Am. J. Cardiol. 120, 2278–2283 (2017).

Li, W. & Somerville, J. Infective endocarditis in the grown-up congenital heart (GUCH) population. Eur. Heart J. 19, 166–173 (1998).

Habib, G. et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur. Heart J. 30, 2369–2413 (2009).

Funding

Unrelated to the study, Lourdes Vicent receives research funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (CM20/00104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

L.V., M.A.G., P.M., M.M.-A., M.V., M.C.F., M.C.-B., A.d.A., M.Á.R.-E., J.M.M., A.J.G.-A., D.d.C.C., E.G.-V., and M.M.-S. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, and to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

All patients provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vicent, L., Goenaga, M.A., Muñoz, P. et al. Infective endocarditis in children and adolescents: a different profile with clinical implications. Pediatr Res 92, 1400–1406 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-01959-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-01959-3

This article is cited by

-

Right-sided infective endocarditis or thrombus? Report of two cases diagnosed by transthoracic echocardiography

Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery (2024)

-

Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases in youths and young adults aged 15–39 years in 204 countries/territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis of Global Burden of Disease Study 2019

BMC Medicine (2023)

-

Infective Endocarditis at a Referral Children’s Hospital During 19-Year Period: Trends and Outcomes

Pediatric Cardiology (2023)