Abstract

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), which is upregulated in activated microglia, is a method for investigating whether immune activation is evident in the brain of adults with schizophrenia. This study aimed to measure TSPO availability in the largest patient group to date, and to compare it between patients with recent onset (ROS) and established (ES) schizophrenia. In total, 20 ROS patients (14 male), 21 ES (13 male), and 21 healthy controls completed the study. Patients were predominantly antipsychotic-medicated. Participants underwent a PET scan using the TSPO-specific radioligand [11C](R)-PK11195. The primary outcome was binding potential (BPND) in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Secondary outcomes were BPND in six other regions. Correlations were investigated between TSPO availability and symptom severity. Data showed that mean BPND was higher in older (ES and controls) compared with younger (ROS and controls) individuals, but did not significantly differ between ROS or ES and their respective age-matched controls (ACC; ANOVA main effect of diagnosis: F1,58 = 0.407, p = 0.526). Compared with controls, BPND was lower in antipsychotic-free (n = 6), but not in medicated, ROS patients. BPND in the ES group was negatively correlated with positive symptoms, and positively correlated with negative symptom score. Our data suggest ageing is associated with higher TSPO but a diagnosis of schizophrenia is not. Rather, subnormal TSPO levels in drug-free recent-onset patients may imply impaired microglial development and/or function, which is counteracted by antipsychotic treatment. The development of novel radioligands for specific immune-mechanisms is needed for further clarification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several lines of evidence suggest that immune activation and inflammation play a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. For example, meta-analyses report increased blood levels of c-reactive protein, IL-6 and a range of other cytokines compared with non-patients and some changes normalise with recovery [1, 2]. However, increases are rarely in the pathological range, and conventional anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin have limited efficacy.

In the last decade, it has become possible to investigate inflammation in the living human using positron emission tomography (PET) in various neurodegenerative disorders. Microglia are the resident macrophages of the central nervous system (CNS) [3]. In their activated immune state, microglia secrete cytokines and chemokines and this is associated with increased expression of the translocator protein (TSPO) for which a number of radioligands have been developed.

Early studies reported increased brain TSPO expression in schizophrenia, suggesting the presence of microglial activation and neuroinflammation [4, 5]. These studies motivated our initial PET study using [11C](R)-PK11195, which found no difference in TSPO expression between medication-free schizophrenia patients and matched healthy subjects [6]. Most other studies have reported unchanged or decreased TSPO expression [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of five studies concluded that PET TSPO radioligand binding is statistically significantly reduced in recent onset schizophrenia unrelated to treatment status [14].

In the present study, we aimed to compare TSPO expression between (i) schizophrenia patients with recent onset of symptoms (ROS group); (ii) an established illness group with at least 10 years of symptoms (ES group); and (iii) healthy controls using [11C](R)-PK11195 PET in order to determine differences across illness stages and to get a more conclusive answer regarding a potential role of microglial activation in schizophrenia. The primary region of interest (ROI) was the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), based on evidence of grey matter loss [15] and increased glutamate content in ACC [16]. Secondary ROIs were based on our previous research [6] and included the prefrontal cortex (PFC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), parietal cortex, temporal cortex, caudate, putamen, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and brainstem.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

In total, 20 recent onset patients (14 males; mean ± standard deviation [SD]: 24.2 ± 5.1 years); 21 established patients (13 males; mean ± SD: 46.0 ± 6.0 years); and 21 age- and sex-matched controls: 10 matched to recent onset (8 males; mean ± SD: 25.5 ± 4.1 years), 11 matched to established patients (7 males; mean ± SD: 47.0 ± 5.0 years) completed the study. It was calculated that a study sample size of 20 participants in each group could detect a between-group difference in binding potential (BPND) of 15%, with a power of 80%, α = 0.05, two-sided. Patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or schizophreniform disorder (all referred to in the paper as “schizophrenia”), as determined by consensus of two clinicians (CG, PST, and/or BD) following case note review and patient interview.

Inclusion criteria for recent onset patients were: <5 years from onset and <12 weeks lifetime exposure to antipsychotic medication, and for established patients >10 years from onset and no major changes to antipsychotic medication over the previous 8 weeks. Controls were age- and sex-matched to patients and included if they had no personal or first-degree relative with a history of psychosis, or a history of depression within the past two years. We excluded participants who: had significant physical illness such as an inflammatory or neurological condition; were taking anti-inflammatory medication; and who met DSM-IV criteria for harmful use of substances within the past month or dependence within the past 6 months. Females could not participate when pregnant or breast-feeding.

For patients, symptom severity was assessed on the day of scanning using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [17] and level of functioning by the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) [18]. Scales were administered and scored by a trained clinician (CG).

The present study was conducted at the University of Manchester (UoM), as part of a multi-centre multi-modal imaging project (the SPRING study) that was conducted at UoM, the University of Nottingham and Cardiff University. The study was approved by the North-West Lancaster National Research Ethics Service Committee and the United Kingdom Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee, and was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), amended in Edinburgh (2000). Participants gave their written informed consent prior to study participation.

Image acquisition

Image acquisition and analysis methodology for this study was similar to recent publications from our group [6, 19]. In summary, a high-resolution T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image was acquired for data-processing, identification of ROIs, and voxel-based morphometry analysis using a 3T Philips Achieva scanner. PET imaging was performed using a High-Resolution Research Tomograph (Siemens). For each PET scan, following a 6 minute transmission scan, [11C](R)-PK11195 was intravenously injected with a target dose of 740MBq. Dynamic emission data were acquired for 60 min. The data was re-binned into 18 frames of variable duration and reconstructed.

Image processing

A summation image was created and co-registered with the T1-weighted MR image using Vinci version 2.55 (Max-Planck Institute for Neurological Research, Cologne, Germany), segmented into grey and white matter using SPM8 (Statistical Parametric Mapping, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, London, UK), and normalised using the n30r83 version of the probabilistic brain-atlas by Hammers et al. [20].

A binary grey matter mask was created in Vinci using a threshold of 0.5. Object maps (standardised anatomical areas) were defined using Analyze 11.0 (BIR, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Parametric images of BPND were created using MICKpm 5.2 (in-house MATLAB based software), using the simplified reference tissue model and the time activity curve from the bilateral grey matter cerebellum as reference tissue input function. BPND for each ROI were read out from the parametric maps by applying the object maps.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS Statistics Version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were analysed by SC, CG, and RH. Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between groups were assessed using independent samples t-tests (2-sided), chi-square test of homogeneity or Fisher’s exact test (two-sided). Between-group differences in BPND in the ACC were assessed using a two-way ANOVA with diagnosis (patients and controls) and age (younger and older) as fixed factors. Between-group differences in BPND in all ROIs (the secondary ROIs) were assessed using repeated-measures ANOVA with brain region (ACC, PFC, OFC, parietal cortex, putamen, thalamus, and brainstem) as the within-subjects factor. The effect size of between-group differences in BPND was calculated as Cohen’s d (the difference between the means divided by the pooled standard deviation).

Shapiro-Wilk’s test and visual inspection of Q-Q plots was done to assess normal distribution and possible outliers. Box’s test was done to assess equality of covariance, Levine’s test to assess homogeneity of variances, and Mauchly’s test to assess sphericity of the data using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction if violated. Differences in individual ROIs were assessed post hoc in an exploratory fashion using independent samples t-tests.

Correlation of regional BPND with PANSS and PSP scores were assessed using Pearson’s r, or Spearman’s coefficients if a measure was not normally distributed. Findings were considered significant at the p < 0.05 (2-sided) level.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics for all participants are outlined in Table 1. An overview of psychotropic medication of the patient groups can be found in the supplement, Tables S1 and S2. Patients and controls were well matched with no significant differences between them in age, sex, BMI or injected mass of [11C](R)-PK11195. A greater proportion of patients were smokers compared with controls. There were no significant differences between recent onset and established patients in PANSS scores, PSP scores, sex or smoking status (Table 1). Established patients had a significantly higher BMI than recent onset patients and, by design, established patients were older and had a significantly longer duration of illness. There was no difference between the patient groups in antidepressant usage. Combining all patients and all controls there was no main effect of sex, BMI, smoking status or injected mass of [11C](R)-PK11195 so these were not included as covariates.

Mean BPND for caudate, amygdala, hippocampus and temporal cortex was around zero (see Supplementary Fig. S1) and these regions were therefore not included in subsequent analyses. The primary dependent variable was BPND in the ACC.

Furthermore, in the supplementary material, data is presented of exploratory post hoc analyses that were carried out to test the significance of any difference in BPND in individual ROIs between our patient groups and matched controls, and to establish any main effect of age or age X diagnosis interaction (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. S2, and Table S4).

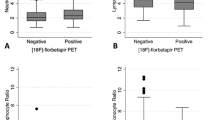

Visual inspection of the data showed that BPND in the ACC was similar between each patient group and its respective control group (Fig. 1a). BPND was greater in established patients and their controls compared with the younger group of recent onset patients and controls. Two-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in BPND between patients and controls (no main effect of diagnosis; F1,58 = 0.41, p = 0.53). There was a significant main effect of age (F1,58 = 15.49, p < 0.001) but no significant age*diagnosis interaction (F1,58 = 0.59, p = 0.45).

Patient binding potential is compared with age and sex-matched controls in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; [a]) and in all regions of interest (ROIs) together (i.e., ACC, PFC, OFC, parietal cortex, putamen, thalamus and brainstem; [b]). Orange symbols represent female participants. Black lines in scatterplot indicate mean ± SEM per group.

Statistical effects of age and diagnosis were similar to ACC across all 7 ROIs (Fig. 1b) with no main effect of diagnosis (F1,58 = 1.45, p = 0.23), a main effect of age (F1,58 = 7.05, p = 0.01), and no significant age*diagnosis interaction (F1,58 = 0.13, p = 0.72). However, there was a significant ROI*diagnosis interaction (F3.152,182.787 = 2.97, p = 0.03) due to statistically significant overall reductions in putamen and thalamus in patients compared with controls (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Table S5). The ROI*diagnosis*age interaction was not significant (F3.152,182.78 = 1.90, p = 0.13).

Patients with recent onset schizophrenia who were antipsychotic-free (n = 6) were compared with those who were currently taking an antipsychotic (n = 14; an overview of their patient characteristics and the matched controls characteristics can be found in Supplementary Table S6). Mean BPND across all ROIs combined was lower in antipsychotic-free patients compared with controls (Fig. 2, Table 2) producing a statistically significant main effect of group (F1,14 = 5.26, p = 0.04). There was no region*group interaction (F(2.043,28.604) = 0.27, p = 0.77). The data for individual ROIs (Table 2) showed that BPND was lower in antipsychotic-free patients compared with controls, with medium (≥0.5) or large (≥0.8) effect sizes in all ROIs. There were no statistical differences in BPND between antipsychotic-exposed patients and their recent onset controls (Supplementary Table S7), or between antipsychotic-free and exposed recent-onset patients (Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table S8). Except in the brainstem, where BPND was higher in antipsychotic-exposed compared with antipsychotic-free patients.

In the established patients, there was a moderate negative correlation between PANSS positive score and [11C](R)-PK11195 BPND in all ROIs except in the brainstem, reaching significance in the ACC, PFC, OFC and putamen (Supplementary Table S9). In contrast, PANSS negative scores positively correlated with BPND in all ROIs, reaching significance in the PFC and OFC. Figure 3 presents the correlation of PANSS positive and negative scores in the OCC, which showed the strongest correlation, and in the ACC, the primary ROI. PANSS general and total scores and the PSP did not correlate with BPND in any region (Supplementary Table S9). The correlation between BPND and clinical measures in patients with recent onset schizophrenia and all patients with schizophrenia can be found in the supplement, Tables S10 and S11, respectively.

Correlation between [11C](R)-PK11195 binding potential (BPND) and scores on the positive (a) and negative (b) subscales of the PANSS in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and scores on the positive (c) and negative (d) subscales of the PANSS in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) across established schizophrenia patients, divided into male and female participants.

A voxel-based morphometry analysis using SPM12 was carried out on the T1-weighted MR images to examine potential differences in grey matter volume between schizophrenia patients and controls. No significant between-group grey matter volume differences were found, suggesting that the significant differences in BPND in our data are unlikely to be an artefact of differences in regional tissue volumes. For details of the VBM methodology, please see Holmes et al. [19].

Discussion

The present study was conducted to determine whether there are differences in regional brain TSPO expression, an indication of microglial activation, across schizophrenia illness stages, and is the largest PET study to investigate potential microglial activation in schizophrenia to date. In the ACC, the primary ROI, there was no main effect of diagnosis and neither the recent onset nor the established group differed from their respective controls in [11C](R)-PK11195 BPND. Similarly there was no main effect of group across all 7 ROIs (i.e., ACC, PFC, PFC, parietal cortex, putamen, thalamus and brainstem) but 2 ROIs differed significantly from the others; in the thalamus and putamen, [11C](R)-PK11195 binding was reduced in the total sample of 40 patients compared with the 20 controls. There was an increase in the older clinical and control groups compared with the younger groups, in line with a previous study using TSPO radioligand [11C]PBR28 [21]. The recent onset group tended to have reduced [11C](R)-PK11195 binding compared with their controls and the reduction was statistically significant in the 6 patients who were not receiving antipsychotics. This pattern of results was repeated in the 6 other secondary cortical and subcortical ROIs in the recent onset patients.

Our study has several limitations. [11C](R)-PK11195 has a relatively poor signal to noise ratio [22] which limits the ability to detect small changes in TSPO binding as might occur in a low level inflammatory condition like schizophrenia. Nevertheless, this does not account for the significant reduction in binding seen in antipsychotic-free patients. The choice of radioligand and analytic methods are discussed in the supplementary material. Having a patient population comprising of schizophrenia, schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorder may contribute to heterogeneity. Currently, there is however no detailed knowledge about neurological differences between these patient groups and we therefore decided not to differentiate between them. Furthermore, clinically significant depressive symptoms might have introduced a tendency towards elevated [11C](R)-PK11195 BPND as shown in previous studies in major depressive disorder [19], yet we did not assess depressive symptoms by means of depression scales. Our results however indicate an absence of increased PET TSPO binding in patients, suggesting no increase was caused by potential depression comorbidity. Our study included relatively few antipsychotic-free patients (n = 6), of whom only two were antipsychotic-naïve. Although all our patients with recent onset schizophrenia had <12 weeks exposure to antipsychotics, our results suggest that even minimal exposure to antipsychotics may have an influence on BPND. Established patients had a long history of exposure to antipsychotic medication, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the effects of illness duration. Our patients were also mainly stable with mild symptom severity, limiting the ability to detect correlations between severity and BPND. It is possible that increased TSPO expression can be found in the prodrome or at the onset of symptoms or in those with treatment resistant schizophrenia. Finally, our study was not designed or powered to investigate between-sex differences in BPND. Visual inspection of Fig. 2, in which antipsychotic-free recent onset patients show significantly lower BPND than matched younger controls, suggests that this difference is driven by the male patients. However, the very small number of females in each group (n = 2) makes it impossible to draw clear conclusions and future studies could investigate this possibility further.

We did not find evidence of increased microglial activation in recent onset patients with minimal (<12 weeks) or no exposure to antipsychotic drugs. The results are in keeping with the majority of previous studies [8,9,10,11,12,13] also showing no TSPO difference between patients and controls, and a recent post-mortem study showing no increase in TSPO in brain tissue of schizophrenia patients [23]. One major study reported increased [11C]PBR28 TSPO binding in people with ultra-high risk for psychosis and with early psychosis [24]. However, the analysis method has been challenged [25]. The data were included in a recent meta-analysis that found no increase in TSPO binding in schizophrenia regardless of disease stage, but on the contrary found strong evidence for reductions that were unrelated to drug treatment [14]. In the present study, we found that BPND was lower in antipsychotic-free recent onset patients across all ROIs compared with matched controls as have other studies [7, 9, 10]. This may potentially reflect a chronic neurodevelopmental abnormality of microglial function in schizophrenia. It is therefore possible that TSPO availability does not accurately reflect low level inflammation in schizophrenia, or that it reflects a reduced ability by the immune system to mount an anti-inflammatory response. Recent studies report promising PET tracers for the quantification of mitochondrial and synaptic function, which in the future might be preferable over TSPO tracers [26].

We also found reduction in all patients compared with controls in the putamen and thalamus in the entire sample. Our findings therefore add to an emerging body of evidence that TSPO availability is reduced in the early years of psychosis and possibly especially apparent in drug-free patients. The fact that reduced BPND was also associated with greater PANSS positive symptom scores in those with many years of illness suggests reduced BPND could be a marker close to an underlying pathogenic mechanism of psychosis.

Reduced TSPO binding in schizophrenia stands in contrast to increases in PET TSPO binding reported in several CNS inflammatory disorders with known pathologies involving microglial activation including stroke, multiple sclerosis, and Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases. Furthermore, we and one other group have recently reported increases in [11C](R)-PK11195 binding in patients with major depression which is associated with mild increases in systemic immune signalling although not with gross CNS inflammatory pathology [19, 27]. Nevertheless, the anti-microglial anti-inflammatory antibiotic, minocycline showed evidence of efficacy in depression in two clinical trials (see [28]), suggesting the raised PET TSPO binding could reflect a causal inflammatory process and possibly microgliosis. In contrast, minocycline was of no benefit in a recent major clinical trial in recent onset schizophrenia, in keeping with the absence of increased PET TSPO binding [28].

A neuroinflammatory process is however not ruled out by the present results. For example, in an infection-mediated neurodevelopmental mouse model of schizophrenia, behavioural abnormalities were associated with raised cytokine concentrations in the PFC but with reduced prefrontal TSPO concentrations with no microglial activation [29]. Furthermore, much of the evidence that inflamed microglia produce increased TSPO expression comes from in vitro rodent studies, but there is evidence that human and rodent microglia may respond differently to immune activation in vitro [30]. Indeed, three recent expression-profiling studies in several post-mortem brain datasets, report no evidence of increased microglial patterns of gene-expression in schizophrenia [31,32,33]. The same studies do, however, report increased astroglial gene expression which could mediate neuronal dysfunction in schizophrenia. Importantly for the present discussion, it is known that astroglia are a principle source of transforming growth factor β in the brain, which has potent effects in shifting microglia into their non-amoeboid phenotype associated with their important role in synaptic remodelling [34,35,36]. Reduced TSPO binding in schizophrenia could thus reflect an increase in the proportion of microglia that are in a low TSPO-expressing synaptic housekeeping state; this shift could be a cause or an effect of the recent evidence for an old hypothesis that excessive synaptic elimination occurs in schizophrenia [37, 38].

Recent onset patients on medication showed no reductions in BPND and this could reflect a normalisation of the process causing the reduction in the drug-free patients or a pro-inflammatory effect of the drugs. There is little evidence of pro-inflammatory effects of antipsychotic drugs in terms of cytokine levels in brains from treated animals or in clinical populations. In the current study, neither lifetime exposure to medication nor current exposure correlated with BPND or symptom ratings (data not shown) but the selection criteria resulted in little variation in treatment exposure within the two clinical groups. In the established group greater BPND correlated with greater negative symptom scores as in our previous study [6]. But lower BPND values were associated with positive symptoms. Positive and negative symptom ratings were, as expected, orthogonal (r = 0.02, n = 41). The findings imply that the two syndromes have an independent pathogenesis which bear an opposite relationship with TSPO expression. The outcome of these two independent processes (the ratio of positive to negative symptoms) determined a remarkable 27–40% of the variance in observed BPND in the three cortical regions.

In conclusion, we report that schizophrenia is not associated with microglial activation as measured by TSPO expression in the early or established phases of the illness. Indeed, reduced TSPO expression was seen in the putamen and thalamus, in antipsychotic-free recent onset patients and in association with positive symptoms in established illness. The results add to a growing body of evidence that reduced TSPO availability may reflect an important aspect of pathogenesis. However, understanding this signal requires the development of PET tracers for the different molecular and cellular components of neuroinflammation that converge to produce the pattern of TSPO expression reported in schizophrenia.

References

Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1696–709.

Miller BJ, Goldsmith DR. Towards an immunophenotype of schizophrenia: progress, potential mechanisms, and future directions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:299–317.

Frost JL, Schafer DP. Microglia: architects of the developing nervous system. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:587–97.

Doorduin J, de Vries EF, Willemsen AT, de Groot JC, Dierckx RA, Klein HC. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia-related psychosis: a PET study. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1801–7.

van Berckel BN, Bossong MG, Boellaard R, Kloet R, Schuitemaker A, Caspers E, et al. Microglia activation in recent-onset schizophrenia: a quantitative (R)-[11C]PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:820–2.

Holmes SE, Hinz R, Drake RJ, Gregory CJ, Conen S, Matthews JC, et al. In vivo imaging of brain microglial activity in antipsychotic-free and medicated schizophrenia: a [(11)C](R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1672–9.

Collste K, Plaven-Sigray P, Fatouros-Bergman H, Victorsson P, Schain M, Forsberg A, et al. Lower levels of the glial cell marker TSPO in drug-naive first-episode psychosis patients as measured using PET and [(11)C]PBR28. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:850–6.

Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Ambinder EB, Ward RE, Minn I, Vranesic M, et al. In vivo markers of inflammatory response in recent-onset schizophrenia: a combined study using [(11)C]DPA-713 PET and analysis of CSF and plasma. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e777.

Di Biase MA, Zalesky A, O’Keefe G, Laskaris L, Baune BT, Weickert CS, et al. PET imaging of putative microglial activation in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis, recently diagnosed and chronically ill with schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1225.

Hafizi S, Tseng HH, Rao N, Selvanathan T, Kenk M, Bazinet RP, et al. Imaging microglial activation in untreated first-episode psychosis: a PET study with [(18)F]FEPPA. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:118–24.

Kenk M, Selvanathan T, Rao N, Suridjan I, Rusjan P, Remington G, et al. Imaging neuroinflammation in gray and white matter in schizophrenia: an in-vivo PET study with [18F]-FEPPA. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:85–93.

Takano A, Arakawa R, Ito H, Tateno A, Takahashi H, Matsumoto R, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptors in patients with chronic schizophrenia: a PET study with [11C]DAA1106. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13:943–50.

van der Doef TF, de Witte LD, Sutterland AL, Jobse E, Yaqub M, Boellaard R, et al. In vivo (R)-[(11)C]PK11195 PET imaging of 18kDa translocator protein in recent onset psychosis. NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2:16031.

Plaven-Sigray P, Matheson GJ, Collste K, Ashok AH, Coughlin JM, Howes OD, et al. Positron emission tomography studies of the glial cell marker translocator protein in patients with psychosis: a meta-analysis using individual participant data. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84:433–42.

Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, Zipursky R, Sharma T, Kahn RS, et al. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:361–70.

Marsman A, van den Heuvel MP, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE. Glutamate in schizophrenia: a focused review and meta-analysis of (1)H-MRS studies. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:120–9.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76.

Nasrallah H, Morosini P, Gagnon DD. Reliability, validity and ability to detect change of the Personal and Social Performance scale in patients with stable schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2008;161:213–24.

Holmes SE, Hinz R, Conen S, Gregory CJ, Matthews JC, Anton-Rodriguez JM, et al. Elevated translocator protein in anterior cingulate in major depression and a role for inflammation in suicidal thinking: a positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:61–9.

Hammers A, Allom R, Koepp MJ, Free SL, Myers R, Lemieux L, et al. Three-dimensional maximum probability atlas of the human brain, with particular reference to the temporal lobe. Hum Brain Mapp. 2003;19:224–47.

Tuisku J, Plaven-Sigray P, Gaiser EC, Airas L, Al-Abdulrasul H, Bruck A, et al. Effects of age, BMI and sex on the glial cell marker TSPO – a multicentre [(11)C]PBR28 HRRT PET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:2329–38. Epub 2019/08/01

Kreisl WC, Fujita M, Fujimura Y, Kimura N, Jenko KJ, Kannan P, et al. Comparison of [(11)C]-(R)-PK 11195 and [(11)C]PBR28, two radioligands for translocator protein (18 kDa) in human and monkey: Implications for positron emission tomographic imaging of this inflammation biomarker. Neuroimage. 2010;49:2924–32.

Sneeboer MAM, van der Doef T, Litjens M, Psy NBB, Melief J, Hol EM, et al. Microglial activation in schizophrenia: Is translocator 18kDa protein (TSPO) the right marker? Schizophr Res. 2020;215:167–72.

Bloomfield PS, Selvaraj S, Veronese M, Rizzo G, Bertoldo A, Owen DR, et al. Microglial activity in people at ultra high risk of psychosis and in schizophrenia: an [(11)C]PBR28 PET brain imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:44–52.

Narendran R, Frankle WG. Comment on analyses and conclusions of “microglial activity in people at ultra high risk of psychosis and in schizophrenia: an [(11)C]PBR28 PET brain imaging study”. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:536–7.

Mansur A, Rabiner EA, Comley RA, Lewis Y, Middleton LT, Huiban M, et al. Characterization of 3 PET Tracers for quantification of mitochondrial and synaptic function in healthy human brain: (18)F-BCPP-EF, (11)C-SA-4503, and (11)C-UCB-J. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:96–103.

Enache D, Pariante CM, Mondelli V. Markers of central inflammation in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining cerebrospinal fluid, positron emission tomography and post-mortem brain tissue. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;81:24–40.

Deakin B, Suckling J, Barnes TRE, Byrne K, Chaudhry IB, Dazzan P, et al. The benefit of minocycline on negative symptoms of schizophrenia in patients with recent-onset psychosis (BeneMin): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:885–94.

Notter T, Coughlin JM, Gschwind T, Weber-Stadlbauer U, Wang Y, Kassiou M, et al. Translational evaluation of translocator protein as a marker of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2018;23:323–34.

Owen DR, Narayan N, Wells L, Healy L, Smyth E, Rabiner EA, et al. Pro-inflammatory activation of primary microglia and macrophages increases 18 kDa translocator protein expression in rodents but not humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:2679–90.

Birnbaum R, Jaffe AE, Chen Q, Shin JH, BrainSeq C, Kleinman JE, et al. Investigating the neuroimmunogenic architecture of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1251–60.

Gandal MJ, Zhang P, Hadjimichael E, Walker RL, Chen C, Liu S, et al. Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science. 2018;362:eaat8127.

Toker L, Mancarci BO, Tripathy S, Pavlidis P. Transcriptomic Evidence for Alterations in Astrocytes and Parvalbumin Interneurons in Subjects With Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84:787–96.

Bialas AR, Stevens B. TGF-beta signaling regulates neuronal C1q expression and developmental synaptic refinement. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1773–82.

Paglinawan R, Malipiero U, Schlapbach R, Frei K, Reith W, Fontana A. TGFbeta directs gene expression of activated microglia to an anti-inflammatory phenotype strongly focusing on chemokine genes and cell migratory genes. Glia. 2003;44:219–31.

Taylor RA, Chang CF, Goods BA, Hammond MD, Mac Grory B, Ai Y, et al. TGF-beta1 modulates microglial phenotype and promotes recovery after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:280–92.

Feinberg I. Schizophrenia: caused by a fault in programmed synaptic elimination during adolescence? J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:319–34.

Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, Davis A, Hammond TR, Kamitaki N, et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature. 2016;530:177–83.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Medical Research Council Experimental Medicine Challenge Full Grant (MR/K020803/1). The study is listed on the NIHR Clinical Research Network portfolio database, CPMS ID: 16781. FC-Z acknowledges the support from grant from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; 2019/13229-2) and financial support from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brazil (CAPES). We would like to thank the PET & MR radiographers, Michael Green – team leader for Radiochemistry Production, Jose Anton-Rodriguez for PET image reconstruction and medical physics, the SPRING partners for helpful discussions and their contribution to define the patient cohorts, and all the participants who took part in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SC has received consultancy fees from Bayer Healthcare LLC. BD reports grants from P1vital and grants and personal fees from Autifony outside the submitted work. PST has received consultancy fees as an Advisory Board member for Galen Limited; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Europe Ltd; myTomorrows; and LivaNova UK Ltd. Between 2018 and 2020 he was PI on a clinical drug trial sponsored by COMPASS Pathways Ltd, UK. No conflict of interest to declare for CG, FC-Z, RH, or RPS.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Conen, S., Gregory, C.J., Hinz, R. et al. Neuroinflammation as measured by positron emission tomography in patients with recent onset and established schizophrenia: implications for immune pathogenesis. Mol Psychiatry 26, 5398–5406 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0829-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0829-y

This article is cited by

-

Immunophenotypes in psychosis: is it a premature inflamm-aging disorder?

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

-

Microglia and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: translating scientific progress into novel therapeutic interventions

Schizophrenia (2023)

-

Microglia sequelae: brain signature of innate immunity in schizophrenia

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Prenatal immune stress blunts microglia reactivity, impairing neurocircuitry

Nature (2022)

-

The role of microglia in neuropsychiatric disorders and suicide

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2022)