Key Points

-

Among the fractures defined as major in FRAX® (hip, upper arm, forearm and clinical vertebral), the percentage of hip fractures is consistent across regions, but that of nonhip fractures varies substantially

-

Economic analyses most often assess spine and hip fractures, but nonvertebral, nonhip fractures are common, lead to twofold increased resource use compared with hip and spine fractures combined, and greatly affect quality of life

-

Obesity is protective against hip fractures but is associated with an increased risk of fractures of the ankle and lower leg

-

The predictive value of specific risk factors differs by skeletal sites and by risk profile for first and subsequent fractures

-

Rates of treatment with antiosteoporotic drugs fall short of guideline recommendations in women at high risk but are perhaps too frequent in women at low risk

Abstract

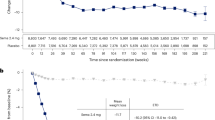

GLOW is an observational, longitudinal, practice-based cohort study of osteoporosis in 60,393 women aged ≥55 years in 10 countries on three continents. In this Review, we present insights from the first 3 years of the study. Despite cost analyses being frequently based on spine and hip fractures, we found that nonvertebral, nonhip fractures were around five times more common and doubled the use of health-care resources compared with hip and spine fractures combined. Fractures not at the four so-called major sites in FRAX® (upper arm, forearm, hip and clinical vertebral fractures) account for >40% of all fractures. The risk of fracture is increased by various comorbidities, such as Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis and lung and heart disease. Obesity, although thought to be protective against all fractures, substantially increased the risk of fractures in the ankle or lower leg. Simple assessment by age plus fracture history has good predictive value for all fractures, but risk profiles differ for first and subsequent fractures. Fractures diminish quality of life as much or more than diabetes mellitus, arthritis and lung disease, yet women substantially underestimate their own fracture risk. Treatment rates in patients at high risk of fracture are below those recommended but might be too frequent in women at low risk. Comorbidities and the limits of current therapeutic regimens jeopardize the efficacy of drugs; new regimens should be explored for severe cases.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Watts, N. B. et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr. Pract. 16, 1016–1019 (2010).

Watts, N. B. Osteoporosis in men. Endocr. Pract. 19, 834–838 (2013).

National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis [online], (2013).

Panneman, M. J., Lips, P., Sen, S. S. & Herings, R. M. Undertreatment with anti-osteoporotic drugs after hospitalization for fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 15, 120–124 (2004).

Hooven, F., Gehlbach, S. H., Pekow, P., Bertone, E. & Benjamin, E. Follow-up treatment for osteoporosis after fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 16, 296–301 (2005).

Teng, G. G., Curtis, J. R. & Saag, K. G. Quality health care gaps in osteoporosis: how can patients, providers, and the health system do a better job? Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 7, 27–34 (2009).

Hooven, F. H. et al. The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW): rationale and study design. Osteoporos. Int. 20, 1107–1116 (2009).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) & National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006 (US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD, 2008).

Brazier, J. E., Walters, S. J., Nicholl, J. P. & Kohler, B. Using the SF-36 and Euroqol on an elderly population. Qual. Life Res. 5, 195–204 (1996).

Brazier, J. E. et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 305, 160–164 (1992).

Pfeilschifter, J. et al. Regional and age-related variations in the proportions of hip fractures and major fractures among postmenopausal women: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women. Osteoporos. Int. 23, 2179–2188 (2012).

Kanis, J. A. on behalf of the WHO Scientific Group. Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical Report. WHO Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases (University of Sheffield, 2007).

Scholes, S. et al. Epidemiology of lifetime fracture prevalence in England: a population study of adults aged 55 years and over. Age Ageing 43, 234–240 (2014).

Amin, S., Achenbach, S. J., Atkinson, E. J., Khosla, S. & Melton, L. J. 3rd. Trends in fracture incidence: a population-based study over 20 years. J. Bone Miner. Res. 29, 581–589 (2014).

Crisp, A. et al. Declining incidence of osteoporotic hip fracture in Australia. Arch. Osteoporos. 7, 179–185 (2012).

Lam, A. et al. Major osteoporotic to hip fracture ratios in Canadian men and women with Swedish comparisons: a population based analysis. J. Bone Miner. Res. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2146.

Ettinger, B., Black, D. M., Dawson-Hughes, B., Pressman, A. R. & Melton, L. J. 3rd. Updated fracture incidence rates for the US version of FRAX. Osteoporos Int. 21, 25–33 (2010).

Kanis, J. A. et al. Long-term risk of osteoporotic fracture in Malmö. Osteoporos. Int. 11, 669–674 (2000).

Leslie, W. D. et al. Secular decreases in fracture rates 1986–2006 for Manitoba, Canada: a population-based analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 22, 2137–2143 (2011).

Gronskag, A. B., Forsmo, S., Romundstad, P., Langhammer, A. & Schei, B. Incidence and seasonal variation in hip fracture incidence among elderly women in Norway. The HUNT Study. Bone 46, 1294–1298 (2010).

Emaus, N. et al. Hip fractures in a city in Northern Norway over 15 years: time trends, seasonal variation and mortality: the Harstad Injury Prevention Study. Osteoporos. Int. 22, 2603–2610 (2011).

Lofthus, C. M. et al. Epidemiology of hip fractures in Oslo, Norway. Bone 29, 413–418 (2001).

Rogmark, C., Sernbo, I., Johnell, O. & Nilsson, J. A. Incidence of hip fractures in Malmo, Sweden, 1992–1995. A trend-break. Acta Orthop. Scand. 70, 19–22 (1999).

Jacobsen, S. J. et al. Seasonal variation in the incidence of hip fracture among white persons aged 65 years and older in the United States, 1984–1987. Am. J. Epidemiol. 133, 996–1004 (1991).

Bischoff-Ferrari, H. A., Orav, J. E., Barrett, J. A. & Baron, J. A. Effect of seasonality and weather on fracture risk in individuals 65 years and older. Osteoporos. Int. 18, 1225–1233 (2007).

Levy, A. R., Bensimon, D. R., Mayo, N. E. & Leighton, H. G. Inclement weather and the risk of hip fracture. Epidemiology 9, 172–177 (1998).

Giladi, A. M. et al. Variation in the incidence of distal radius fractures in the US elderly as related to slippery weather conditions. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 133, 321–332 (2014).

Modarres, R., Ouarda, T. B., Vanasse, A., Orzanco, M. G. & Gosselin, P. Modeling seasonal variation of hip fracture in Montreal, Canada. Bone 50, 909–916 (2012).

Øyen, J., Rhode, G. E., Hochberg, M., Johnsen, V. & Haugeberg, G. Low-energy distal radius fractures in middle-aged and elderly women—seasonal variations, prevalence of osteoporosis, and associates with fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 21, 1247–1255 (2010).

Iolascon, G., Gravina, P., Luciano, F., Palladino, C. & Gimigliano, F. Characteristics and circumstances of falls in hip fractures. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 25 (Suppl. 1), S133–S135 (2013).

Costa, E. et al. When, where and how osteoporosis-associated fractures occur: an analysis from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). PLoS ONE 8, e83306 (2013).

Arakaki, H. et al. Epidemiology of hip fractures in Okinawa, Japan. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 29, 309–314 (2011).

Karantana, A. et al. Epidemiology and outcome of fracture of the hip in women aged 65 years and under: a cohort study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 93, 658–664 (2011).

Bischoff-Ferrari, H. A. The role of falls in fracture prediction. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 9, 116–121 (2011).

Nevitt, M. C., Cummings, S. R. & The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Type of fall and risk of hip and wrist fractures: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 41, 1226–1234 (1993).

Morrison, A., Fan, T., Sen, S. S. & Weisenfluh, L. Epidemiology of falls and osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review. Clinicoecon. Outcomes Res. 5, 9–18 (2013).

Adachi, J. D. et al. Impact of prevalent fractures on quality of life: baseline results from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. Mayo Clin. Proc. 85, 806–813 (2010).

Roux, C. et al. Burden of non-hip, non-vertebral fractures on quality of life in postmenopausal women: the Global Longitudinal study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Osteoporos. Int. 23, 2863–2871 (2012).

Ioannidis, G. et al. Non-hip, non-spine fractures drive healthcare utilization following a fracture: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Osteoporos. Int. 24, 59–67 (2013).

Compston, J. E. et al. Obesity, health-care utilization, and health-related quality of life after fracture in postmenopausal women: Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Calc. Tissue Int. 94, 223–231 (2014).

Díez-Pérez, A. et al. Regional differences in treatment for osteoporosis. The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Bone 49, 493–498 (2011).

Guggina, P. et al. Characteristics associated with anti-osteoporosis medication use: data from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW) USA cohort. Bone 51, 975–980 (2012).

Siris, E. S. et al. Failure to perceive increased risk of fracture in women 55 years and older: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Osteoporos. Int. 22, 27–35 (2011).

Tom, S. E. et al. Frailty and fracture, disability, and falls: a multiple country study from the global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women. J. Am. Geriatr Soc. 61, 327–334 (2013).

Greenspan, S. L. et al. Predictors of treatment with osteoporosis medications after recent fragility fractures in a multinational cohort of postmenopausal women. J. Am. Geriatr Soc. 60, 455–461 (2012).

Compston, J. E. et al. Obesity is not protective against fracture in postmenopausal women: GLOW. Am. J. Med. 124, 1043–1050 (2011).

Sambrook, P. N. et al. Predicting fractures in an international cohort using risk factor algorithms without BMD. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 2770–2777 (2011).

Compston, J. E. et al. Relationship of weight, height, and body mass index with fracture risk at different sites in postmenopausal women: The global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women (GLOW). J. Bone Miner. Res. 29, 487–493 (2014).

Díez-Pérez, A. et al. Risk factors for treatment failure with antiosteoporosis medication: The global longitudinal study of osteoporosis in women (GLOW). J. Bone Miner. Res. 29, 260–267 (2014).

FitzGerald, G. et al. Differing risk profiles for individual fracture sites: evidence from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1907–1915 (2012).

Gregson, C. L. et al. Disease-specific perception of fracture risk and incident fracture rates: GLOW cohort study. Osteoporos. Int. 25, 85–95 (2014).

Adachi, J. D. et al. Fracture patterns with use of selective serotonin receptor inhibitors, proton pump inhibitors and glucocorticoids in a large international observational study. Presented at the ASBMR 2013 Annual Meeting [abstract 1049].

Warriner, A. et al. Osteoporosis medication adherence: reasons for stopping and not starting. Presented at ACR/ARHP Annual Meeting 13 [abstract 1243].

Gehlbach, S. et al. Previous fractures at multiple sites increase the risk for subsequent fractures: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 645–653 (2012).

Stone, K. L. et al. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 1947–1954 (2003).

van Staa, T. P., Leufkens, H. G. & Cooper, C. Does a fracture at one site predict later fractures at other sites? A British cohort study. Osteoporos. Int. 13, 624–629 (2002).

Dennison, E. M. et al. Effect of co-morbidities on fracture risk: findings from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Bone 50, 1288–1293 (2012).

Prieto-Alhambra, D. et al. An increased rate of falling leads to a rise in fracture risk in postmenopausal women with self-reported osteoarthritis: a prospective multinational cohort study (GLOW). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 911–917 (2013).

Fried, L. P. et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56, M146–M156 (2001).

Tang, X. et al. Obesity and risk of hip fracture in adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. PLoS ONE 12, e55077 (2013).

Nielson, C. M., Srikanth, P. & Orwoll, E. S. Obesity and fracture in men and women: an epidemiologic perspective. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1–10 (2012).

Beck, T. J. et al. Does obesity really make the femur stronger? BMD, geometry, and fracture incidence in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 1369–1379 (2009).

Garvan Institute. Fracture risk calculator [online].

Ohman, E. M., Granger, C. B., Harrington, R. A. & Lee, K. L. Risk stratification and therapeutic decision making in acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 284, 876–878 (2000).

Harrell, F. E. Jr, Califf, R. M., Pryor, D. B., Lee, K. L. & Rosati, R. A. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA 247, 2543–2546 (1982).

Chen, J. S., Hogan, C., Lyubomirsky, G. & Sambrook, P. N. Women with cardiovascular disease have increased risk of osteoporotic fracture. Calcif. Tissue Int. 88, 9–15 (2011).

Drake, M. T. et al. Clinical review. Risk factors for low bone mass-related fractures in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 1861–1870 (2012).

Janghorbani, M., Van Dam, R. M., Willett, W. C. & Hu, F. B. Systematic review of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of fracture. Am. J. Epidemiol. 166, 495–505 (2007).

Vestergaard, P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes—a meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 18, 427–444 (2007).

Loke, Y. K., Cavallazzi, R. & Singh, S. Risk of fractures with inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Thorax 66, 699–708 (2011).

David, C. et al. Severity of osteoporosis: what is the impact of co-morbidities? Joint Bone Spine 77 (Suppl. 2), S103–S106 (2010).

Bazelier, M. T. et al. Risk of fractures in patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Neurology 78, 1967–1973 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The GLOW study was supported by the Alliance for Better Bone Health (Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi-Aventis), the Warner Chilcott Company and Sanofi-Aventis. We thank S. Rushton-Smith for coordinating revisions and providing editorial assistance, including editing, checking content and language, formatting and referencing, A. Wyman for checking the statistical findings and editing the tables, figures and results, and G. FitzGerald, E. Siris and J. Compston for reviewing manuscript sections.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

N.B.W. is co-founder, stockholder and director of OsteoDynamics; has received honoraria for lectures from Amgen and Merck in the past year; has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amarin, Amgen, Bristol–Myers Squibb, Corcept, Endo, Imagepace, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Noven, Pfizer/Wyeth, Radius and Sanofi-Aventis in the past year; and, through his Health System, has received research support from Merck and NPS Pharmaceuticals.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watts, N. Insights from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Nat Rev Endocrinol 10, 412–422 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.55

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.55

This article is cited by

-

Introduction to Osteoporosis, Osteomalacia, and Fragility Fractures

Indian Journal of Orthopaedics (2023)

-

Fracture distribution in postmenopausal women: a FRISBEE sub-study

Archives of Osteoporosis (2022)

-

Evaluating the performance of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) in fracture risk prediction and developing a new Charlson Fracture Index (CFI): a register-based cohort study

Osteoporosis International (2022)

-

Comorbidity and osteoporotic fracture: approach through predictive modeling techniques using the OSTEOMED registry

Aging Clinical and Experimental Research (2022)

-

Moringa oleifera leaf extracts protect BMSC osteogenic induction following peroxidative damage by activating the PI3K/Akt/Foxo1 pathway

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2021)