Abstract

Purpose

Preoperative frailty assessment is recommended by multiple practice guidelines and may improve outcomes, but it is not routinely performed. The barriers and facilitators of routine preoperative frailty assessment have not been formally assessed. Our objective was to perform a theory-guided evaluation of barriers and facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment.

Methods

This was a research ethics board-approved qualitative study involving physicians who perform preoperative assessment (consultant and resident anesthesiologists and consultant surgeons). Semistructured interviews were conducted by a trained research assistant informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and facilitators to frailty assessment. Interview transcripts were independently coded by two research assistants to identify specific beliefs relevant to each theoretical domain.

Results

We interviewed 28 clinicians (nine consultant anesthesiologists, nine consultant surgeons, and ten anesthesiology residents). Six domains (Knowledge [100%], Social Influences [96%], Social Professional Role and Identity [96%], Beliefs about Capabilities [93%], Goals [93%], and Intentions [93%]) were identified by > 90% of respondents. The most common barriers identified were prioritization of other aspects of assessment (e.g., cardio/respiratory) and a lack of awareness of evidence and guidelines supporting frailty assessment. The most common facilitators were a high degree of familiarity with frailty, recognition of the importance of frailty assessment, and strong intentions to perform frailty assessment.

Conclusion

Barriers and facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment are multidimensional, but generally consistent across different types of perioperative physicians. Knowledge of barriers and facilitators can guide development of evidence-based strategies to increase frailty assessment.

Résumé

Objectif

L’évaluation préopératoire de la fragilité est recommandée par plusieurs lignes directrices de pratique et pourrait améliorer les devenirs, mais elle n’est pas systématiquement réalisée. Les obstacles et les facilitateurs de l’évaluation de routine de la fragilité préopératoire n’ont pas été officiellement évalués. Notre objectif était de mener une évaluation théorique des obstacles et des facilitateurs de l’évaluation préopératoire de la fragilité.

Méthode

Il s’agissait d’une étude qualitative approuvée par le comité d’éthique de la recherche impliquant des médecins menant des évaluations préopératoires (anesthésiologistes, résidents en anesthésiologie et chirurgiens). Des entrevues semi-structurées ont été réalisées par un assistant de recherche formé en se fondant sur le Cadre des domaines théoriques afin d’identifier les obstacles et les facilitateurs à l’évaluation de la fragilité. Les transcriptions des entrevues ont été codées de manière indépendante par deux assistants de recherche afin d’identifier les croyances spécifiques pertinentes à chaque domaine théorique.

Résultats

Nous avons interrogé 28 cliniciens (neuf anesthésiologistes, neuf chirurgiens et dix résidents en anesthésiologie). Six domaines (Connaissances [100 %], Influences sociales [96 %], Rôle et identité socio-professionnels [96 %], Croyances concernant les capacités [93 %], Objectifs [93 %] et Intentions [93 %]) ont été identifiés par > 90 % des répondants. Les obstacles les plus fréquemment cités étaient la priorisation accordée à d’autres aspects de l’évaluation (p. ex., cardio/respiratoire) et le manque de connaissances des données probantes et des lignes directrices à l’appui de l’évaluation de la fragilité. Les facilitateurs les plus courants étaient un degré élevé de familiarité avec la fragilité, la reconnaissance de l’importance de l’évaluation de la fragilité et de fortes intentions de réaliser une évaluation de la fragilité.

Conclusion

Les obstacles et les facilitateurs de l’évaluation préopératoire de la fragilité sont multidimensionnels, mais généralement uniformes parmi les différents types de médecins périopératoires. La connaissance des obstacles et des facilitateurs peut guider l’élaboration de stratégies fondées sur des données probantes pour augmenter l’évaluation de la fragilité.

Similar content being viewed by others

Frailty, a state related to accumulation of age- and disease-related deficits across multiple domains,1,2 is a robust predictor of adverse perioperative outcomes. Systematic reviews demonstrate that frailty is associated with a twofold or greater increase in the risk of morbidity, mortality, and patient-reported disability.3,4,5 Frailty is also associated with a fivefold or greater odds of non-home discharge,6,7 and reviews identify frailty among the strongest predictors of postoperative delirium.8 Older people with frailty consume substantially greater resources via longer and more complex hospital stays, as well as need for postdischarge support.3,6 Importantly, frailty status appears to outperform traditional perioperative risk stratification and adds unique prognostic information when added to typical risk factors considered in preoperative assessment.9,10,11

Given the evidence associating frailty with adverse outcomes, best practice guidelines recommend that frailty assessment be routinely performed in all older adults before surgery. The first of these guidelines was published in 2012.12,13,14,15 Frailty assessment can facilitate identification of a relatively homogeneous high-risk stratum of the older surgical population, may guide identification of frailty-related risk factors,16,17 and could facilitate optimization.18,19 Furthermore, frailty assessment could help to ensure fully informed consent, shared decision-making, and facilitate perioperative care planning (such as engagement of proactive geriatric shared care).20,21 Finally, preliminary evidence suggests that simply identifying frailty status and communicating its presence to the perioperative team may improve outcomes for older surgical patients.22

Despite these recommendations, contemporary data show that frailty assessment is rarely performed in routine preoperative care.23,24 This suggests that evidence- and theory-based implementation interventions may be required to successfully ingrain frailty assessment in the preoperative care of older people.25 Therefore, we undertook a qualitative assessment of barriers and facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment guided by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), a validated 14-domain behavior change and implementation framework based on 33 underlying theories of behavior change.25,26 We aimed to identify barriers and facilitators across consultant and resident anesthesiologists, as well as consultant surgeons, that could guide future design of implementation strategies.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting, and participants

We conducted a descriptive qualitative study27,28 using semi-structured 1:1 interviews with consultant and resident anesthesiologists and consultant surgeons. These were the three key groups who performed preoperative assessment at a 900-bed academic health sciences network that provides 40,000 annual surgical procedures to a catchment area of 1.2 million people across three geographically distinct campuses (The Ottawa Hospital [TOH], with two inpatient hospitals and one dedicated ambulatory surgical centre). Perioperative care at TOH is provided for noncardiac surgical procedures, and the network is the regional referral centre for oncology, complex orthopedics, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, thoracic surgery, otolaryngology, general surgery, plastic surgery, and gynecology. Consultant anesthesiologists (n = 70) at TOH typically have fellowship training, and the anesthesiology residency training program consists of approximately 55 residents. Surgical consultants are typically fellowship trained and make up a department of approximately 150 members. Preoperative evaluation of elective surgical patients consists of a surgical consultation (where the decision to operate is made), followed by assessment by a consultant anesthesiologist in a dedicated preoperative assessment unit if standardized operative or patient complexity triggers are present (see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] eAppendix 1). Urgent and emergency patients are assessed before surgery by an anesthesiology resident (supervised by on-site 24-hr consultant staffing) in-hospital based on request from the surgical service. Ethics approval was granted by The Ottawa Health Sciences Network Research Ethics Board (Ottawa, ON, Canada; OHSN-REB Protocol #20150074-01H). Reporting followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.29

Identification of participants and sample size

We used a quasi-experimental sampling strategy to identify study participants. Separate lists were created of all consultant anesthesiologists, surgeons, and anesthesiology residents. Potential key informants were arranged in ascending order according to their last name, and each informant was assigned a random number. The list was then sorted in descending order to identify the first key informant. Subsequent key informants were selected according to regular intervals, known as periods (determined by dividing the population size [N on the list] by the expected group sample size [n = 8 in our case]). The first participants from each period (i.e., group of N/8) were emailed a recruitment script and were instructed to contact the study coordinator if they were interested and willing to participate. If they were not, we contacted the next potential participant in that period. At the time of the interview, written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Our sample size was based on the concept of thematic saturation or, in other words, sampling until no new domain-level barriers or facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment were identified within a key informant group. Saturation was considered at the informant group level as each group performs substantively different types of preoperative assessment. We expected to perform at least eight interviews in each informant group, and used a stopping criterion of three (i.e., if three consecutive interviews led to no new theoretical domains being identified, we ceased data collection).30 We achieved thematic saturation after conducting 28 interviews (nine with staff anesthesiologists; ten with anesthesiology residents; nine with staff surgeons).

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

The study team approached the question of identifying barriers and facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment pragmatically, meaning that we did not enter the conduct of this study through prioritizing a specific epistemology, but were motivated directly to focus on what could be achieved and meaningfully inform practice. This approach requires a problem-focused approach to the question, while recognizing that there is unlikely to be one way to help solve a problem and begin to find the truth.31 While the pragmatic paradigm is said to align most directly with mixed-methods approaches, the current study is not specifically a mixed-methods design. Instead, it was conceived and analyzed within the context of a larger research program that uses a variety of designs to better understand patient- and system-level approaches to improving outcomes for vulnerable older people with surgery who require surgery.

The research team engaged in reflexivity processes and had several team meetings to discuss analysis. The members of the research team discussed how their individual experiences and contexts may inform aspects of the analysis and how they are reciprocally affected by being in the field of frailty research. Coding and theming decisions involved dialog around these reflexive processes.32

Interviews were conducted and coded by research assistants with no direct relationship to the key informants. One had a background in exercise psychology, and the second in epidemiology. While both were new to the field of perioperative frailty research (≤ three years experience), they had gained exposure to preoperative frailty assessment and the clinical environment where patients are seen for their preoperative assessment. The senior author who reviewed belief statements and final categorization worked in the same institution as the key informants and brought expertise in quantitative methods and frailty research. Through discussion, it became evident that each team member believed in multiple realities and the value of developing knowledge through both qualitative and quantitative research. Further, because of the nature of the research question, all team members approached this study in a pragmatic manner to better understand why preoperative frailty assessments are not routinely conducted. The research team maintained an ongoing, reflexive dialog about their individual contexts and the value of qualitative interviews for developing knowledge, while trying to answer the research question situated within a pragmatic paradigm.

Data collection

We conducted semistructured interviews using an interview guide informed by the TDF (ESM eAppendix 2), which is a behavior change framework that comprises 14 theoretical domains derived from 128 constructs from a synthesis of 33 different theories of health, behavioral, and social psychology that explain changes in health-related behavior. The framework was developed by health psychology theorists, health services researchers, and health psychologists, and has been widely used in implementation research.25,33 Interviews were conducted by phone or in-person (at the convenience of the interviewee), and were digitally recorded. Standard prompts were available to the interviewers. To support description our sample, we asked key informants to self-report their gender, age, years in practice (including residency), fellowship training (or plan for fellowship training for residents), average number of weekly preoperative assessments performed, and percent of preoperative assessments of people ≥ 65 yr.

Analysis

All interview recordings were transcribed verbatim and verified by the interviewers prior to analysis. Any identifying information was removed from the transcripts. Data were analyzed using NVivo 9 software (QSR International, Burlington, MA, USA). Analysis was performed using the following three steps:25,34

STEP 1: CODING INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS

Using directed content analysis,25,35 two team members (C. S., K. D.) independently coded responses from the first two interviews into the theoretical domains and then compared their results to develop a coding scheme; this predominantly represents a deductive approach to coding. Thereafter, all coding was guided by the coding scheme to reduce subjective bias.36 The coders met frequently (after every three interviews) to review their coding and seek consensus. Coder reliability between the two coders was assessed using a method proposed by Miles and Huberman: coder reliability = number of agreements/(total number of agreements + disagreements).37 In instances of disagreement, coders and the senior author (D. I. M.) discussed the rationale behind the coding and came to consensus on an agreed code.

STEP 2: GENERATION OF SPECIFIC BELIEFS

Statements describing specific underlying beliefs were generated for each response within each theoretical domain by one team member (K. D.). These were double-checked by the second coder and the senior author (C. S., D. I. M.). Specific beliefs were generated for each clinician group (staff anesthesiologists, anesthesiology residents, and staff surgeons). A specific belief refers to a collection of responses with a similar underlying theme that suggests a problem and/or influence of the belief on the target behavior.34,38,39 A frequency count (i.e., number of key informants)/belief statement was derived across the interviews in the three subgroups identified above. Each specific belief was then classified as a barrier, facilitator, or a barrier and facilitator by the two coders and the senior author.

STEP 3: IDENTIFYING RELEVANT THEORETICAL DOMAINS, THEMES AND BARRIERS, AND FACILITATORS

In line with guidelines previously published,34,38,39 we grouped specific belief statements into larger themes and then ascertained which of the 14 TDF theoretical domains were relevant to each theme as it aligned with our target behavior. Domains that contained specific beliefs and themes and fulfilled the following three criteria were judged as relevant: relatively high frequency of specific beliefs; the presence of conflicting beliefs; and evidence of strong beliefs that may affect the behavior. All three criteria were considered simultaneously in determining relevance of the theoretical domains. Barriers and facilitators were identified by categorizing each belief statement as a barrier, a facilitator, or both. This categorization was initially done by consensus by the two coders and the senior author, and then reviewed by the larger team.

During peer review, we were further asked to consider the trustworthiness of our study using Lincoln and Guba’s criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.40

Results

Participants

We contacted 31 potential key informants to enroll our final sample of 28 key informants (November 2015 to June 2017; nine staff anesthesiologists; ten anesthesiology residents; nine staff surgeons). Characteristics of these key informants are provided in Table 1. Anesthesiology and surgery consultants were more likely to be male and more anesthesiology residents were female. Average years in practice were higher for consultant anesthesiologists than for surgeons. Anesthesiology key informants included individuals with and without subspecialty training (regional anesthesia, neuroanesthesia, medical education). Surgical consultants came from general, orthopedic, urologic, vascular, and gynecologic surgery. All key informants performed preoperative assessments multiple times per month. The mean interview was 21 min (range, 9–50 min). Coders spent an hour or more immersing themselves with each interview transcript, including reading and rereading transcripts prior to coding. Interview transcripts were then revisited for approximately 40 min each during team meetings (which occurred after every three interviews).

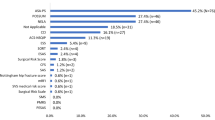

Summary of theoretical domains

Thirteen of 14 theoretical domains were identified by informants through generation of specific beliefs (no specific beliefs were generated in the Optimism domain); six domains (Knowledge [100%], Social Influences [96%], Social Professional Role and Identity [96%], Beliefs about Capabilities [93%], Goals [93%], and Intentions [93%]) were identified by over 90% of informants; 13 were identified by at least 50% of key informants (ESM eAppendix 3). Thirty-eight themes were identified, which included 80 specific belief statements. The Knowledge domain and the Environment, Context, and Resources domain contained the most specific belief statements (n = 11), while the Intentions and Emotions domains contained the fewest specific belief statements (n = 3).

Facilitators of preoperative frailty assessment

Across key informant groups, nine specific beliefs representing seven theoretical domains were identified as facilitators of preoperative frailty assessment by 50% or more of key informants (Table 2; all facilitatory specific beliefs in ESM eAppendix 4). In the Knowledge domain, all key informants identified being conceptually familiar with frailty, and understood that frailty was related to decreased reserve and poor tolerance of stress. Across the three informant groups, there was also agreement that frailty was associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes. Residents, anesthesiologists, and surgeons also consistently identified the importance of frailty assessment for patients preparing for surgery, and ranked it as a relatively high priority in their approach to preoperative assessment. Among residents and staff anesthesiologists, the concept of an integrated frailty instrument within the preoperative health record was a clear facilitator. Surgeons who did not use a preoperative electronic record were less likely to identify this specific belief. Recognition of the impact of an aging surgical population appeared to underlie strong intentions to perform frailty assessment moving forward.

Barriers to preoperative frailty assessment

Nine specific beliefs were also identified as barriers to preoperative frailty assessment by most key informants (across eight theoretical domains, Table 3; see all barrier-related specific beliefs in ESM eAppendix 5). These specific beliefs were ones that the research team thought were not directionally consistent with a clear barrier or facilitator role. For example, all informant groups identified the presence of a structured tool or process as a requirement to increase the uptake of frailty assessment, but no single tool exists to assess frailty.16 Goals were a major barrier as informants identified assessment of cardiorespiratory status and pathology-related indications for surgery as higher priority than frailty assessment. Knowledge-related barriers were identified, including a lack of awareness of best-practice guidelines and evidence supporting frailty assessment. In terms of the Environment, Context, and Resources domain and the Beliefs about Capabilities domain, clear barriers were lack of time in a busy clinic and the need for extra time to complete frailty assessment. Informants also identified issues related to Skills, specifically the need to have experience to perform frailty assessment, as well as barriers related to their Social Professional Role and Identity, as frailty assessment was not a standard part of most clinicians’ preoperative practice. Behavioral Regulation was reported as a barrier because education in supporting frailty assessment was lacking.

Specific beliefs acting as barriers or facilitators

Four specific beliefs in three theoretical domains were identified as potential barriers or facilitators (Table 4; see all specific beliefs coded as barriers and facilitators in ESM eAppendix 6). In the Behavioral Regulation domain, a need for a standardized tool to support frailty assessment was identified, while in the Emotions domain, emotions were not likely to influence frailty assessment. In the Social Influences domain, informants said that social influences from patients or other healthcare providers did not impact their performance of the preoperative frailty assessment.

Assessment of trustworthiness

The credibility of our data should be supported by our approach to interviews and key informants. Interviews were scheduled to prioritize convenience for key informants, and interviews were conducted for as long as key informants wished to engage. Probing questions were used to elicit further information if first-level questions did not yield substantial response. We triangulated our findings across three related key informant groups, and multiple team members checked and coded study data. These data and findings were then further discussed with the senior author, ensuring regular debriefing. Transferability was supported by thick description, achieved in our semistructured interviews through use of probing questions, along with collection of qualitative data from different key informant groups. Furthermore, our sample size was expanded until thematic saturation was achieved. Clear records of study transcripts, coding, thematic analysis, and generation of belief statements support dependability. No external auditing was required or initiated.

Discussion

In this theory-guided qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment, consultant surgeons, consultant anesthesiologists, and anesthesiology residents identified barriers and facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment using the TDF. Important and commonly identified facilitators included familiarity with the concept of frailty and the implications of frailty in predicting adverse outcomes. Frailty assessment was seen as a high-priority area in preoperative care. Key barriers were greater prioritization of assessment of cardiorespiratory status and pathology-related indications for surgery and a lack of time required to perform frailty assessment. Together, these barriers and facilitators could be combined with evidence-based implementation strategies to guide efforts to increase preoperative frailty assessment of older people.

Multiple organizations recommend routine frailty assessment when evaluating older people before surgery; however, data from multiple countries suggest that preoperative frailty assessment is rarely performed. A survey of anesthesiologists in the USA found that only 2% of respondents routinely performed a frailty assessment.23 Similarly, a single-centre survey of surgeons, nurses, and allied health professionals found that < 20% of respondents routinely performed frailty assessments despite their involvement in a multicomponent program to improve outcomes for older surgical patients that included frailty assessment.24 Even these estimates may be upwardly biased as both surveys suffered from low and nondifferential response rates. Eamer et al. also elicited perceived barriers to frailty assessment and identified a lack of staff and physical resources, a lack of knowledge of frailty and frailty assessment, and a lack of training as key barriers,24 although the survey was not guided by any specific behavior change framework.

In the current study, where interviews were guided by the TDF (a widely used behavior change framework in implementation science), our key informants identified barriers similar to those previously elicited, while also identifying novel barriers and facilitators. A lack of time is often identified as a barrier to many recommended healthcare professional behaviors.41,42 Therefore, it was not surprising that surgeons and anesthesiologists identified the time required to perform a frailty assessment and a lack of time in busy clinics as key barriers. Accumulating evidence suggests that this barrier could be addressed using the Clinical Frailty Scale,1 which typically adds less than one minute to a preoperative assessment; operationalization of an electronic frailty instrument to automatically ascertain frailty status using pre-existing health record data could also save time.7,43 A lack of skills and knowledge were also identified as barriers in our study. Evidence-based strategies to address these domains include provision of information, practice, and others.26 Existing online tutorials that combine up-to-date information on frailty, demonstrate best practices in assessment, and allow users to practice frailty assessment could help to address these barriers.44 Finally, future research comparing the accuracy and feasibility of existing tools should help to standardize approaches to assessment, which could be triggered by prompts in electronic health records to address barriers related to memory.45,46

Evidence-based tools and interventions to address many of the highest priority barriers to preoperative frailty assessment suggest that structured implementation efforts could successfully increase uptake. The numerous facilitators identified in our study could further enhance such efforts. First, despite a lack of knowledge related to specifics of frailty instruments and guidelines supporting their use, clinicians were familiar with the concept of frailty and its importance as a prognostic factor. Furthermore, although lower priority than some aspects of assessment, frailty was still identified as a high-priority aspect of preoperative evaluation. Some clinicians also identified that having an instrument embedded in the health record could facilitate the performance of assessments. Therefore, leveraging clinicians’ goals and pre-existing knowledge while optimizing their environment and resources could potentially facilitate substantially higher rates of frailty assessment.

While using barriers and facilitators to identify and design evidence-based interventions to increase guideline-recommended frailty assessment, specific design considerations will also need to consider the type of clinician performing assessment as different informant groups did identify different specific beliefs related to frailty assessment.47 For example, consultants (who typically performed assessments in a clinic) were more likely to identify a lack of time as a barrier than residents who perform assessments on a by-request basis on the ward. Furthermore, surgeons were less likely to feel that extra education was needed to perform frailty assessment but were also less likely to express confidence in their ability to perform a frailty assessment. Residents were more likely to express knowledge of the prognostic importance of frailty, which may reflect its relatively recent emergence in the perioperative literature.

Strengths and limitations

This study should be considered in light of its strengths and limitations. First, the study was conducted using a quasi-experimental sampling strategy to support enrollment of a representative group of informants who were interviewed using standardized techniques guided by a TDF-informed guide until thematic saturation was achieved. Coding, generation of belief statements, and identification of relevant theoretical domains were in duplicate and followed best practices. We interviewed three informant groups who were involved in preoperative assessment to provide a broader overview of barriers and facilitators. Nevertheless, limitations also exist. We did not interview nurses or internists, who are often involved in preoperative assessment, and took no direct efforts to protect from social desirability bias. Our informants were recruited from a multi-hospital network, but the generalizability of our findings remains to be determined as all hospitals were in a single city and affiliated with the same university. In fact, we understand generalizability to be a controversial concept in some aspects of qualitative research.48 This is especially important as approaches to preoperative assessment and environmental context and resources are likely to differ between hospitals and jurisdictions. While the TDF is a well-studied framework with well-established methods, our findings are directly influenced by this framework. We acknowledge that a different approach to qualitative research, sampling, and coding in this content area could give different findings.

Conclusions

In a qualitative study guided by the TDF, we identified key barriers and facilitators to preoperative frailty assessment by anesthesiology and surgery consultants, and anesthesiology residents. Future interventions may need to focus on time-efficient approaches to frailty assessment using standardized tools and prompts. Further focus on providing knowledge and experience to clinicians asked to perform frailty assessment could leverage wide general knowledge of frailty and its prognostic importance to support wider scale uptake of frailty assessment in older surgical patients.

References

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005; 173: 489–95. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: M146–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146

Aucoin SD, Hao M, Sohi R, et al. Accuracy and feasibility of clinically applied frailty instruments before surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 2020; 133: 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000003257

Kim DH, Kim CA, Placide S, Lipsitz LA, Marcantonio ER. Preoperative frailty assessment and outcomes at 6 months or later in older adults undergoing cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Intern Med 2016; 65: 650–60. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-0652

Lin HS, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 2016; 16: 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0329-8

McIsaac DI, Beaulé PE, Bryson GL, Van Walraven C. The impact of frailty on outcomes and healthcare resource usage after total joint arthroplasty: a population-based cohort study. Bone Joint J 2016; 98–B: 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620x.98b6.37124

McIsaac DI, Taljaard M, Bryson GL, et al. Frailty as a Predictor of death or new disability after surgery: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg 2020; 271: 283–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000002967

Watt J, Tricco AC, Talbot-Hamon C, et al. Identifying older adults at risk of delirium following elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2018; 33: 500–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4204-x

Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg 2010; 210: 901–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028

McIsaac DI, Aucoin SD, van Walraven C. A Bayesian comparison of frailty instruments in noncardiac surgery: a cohort study. Anesth Analg 2021; 33: 366–73. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000005290

McIsaac DI, Harris EP, Hladkowicz E, et al. Prospective comparison of preoperative predictive performance between 3 leading frailty instruments. Anesth Analg 2020; 131: 263–72. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000004475

Chow WB, Rosenthal RA, Merkow RP, et al. Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg 2012; 215: 453–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.017

Griffiths R, Beech F, Brown A, et al. Peri-operative care of the elderly 2014: Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Anaesthesia 2014; 69: 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.12524

Alvarez-Nebreda ML, Bentov N, Urman RD, et al. Recommendations for preoperative management of frailty from the Society for Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement (SPAQI). J Clin Anesth 2018; 47: 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2018.02.011

Centre for Perioperative Care. Guideline for perioperative care for people living with frailty undergoing elective and emergency surgery 2021. Available from URL: https://www.cpoc.org.uk/sites/cpoc/files/documents/2021-09/CPOC-BGS-Frailty-Guideline-2021.pdf (accessed June 2022).

McIsaac DI, MacDonald DB, Aucoin SD. Frailty for perioperative clinicians: a narrative review. Anesth Analg 2020; 130: 1450–60. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000004602

Robinson TN, Walston JD, Brummel NE, et al. Frailty for surgeons: review of a national institute on aging conference on frailty for specialists. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 1083–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.08.428

Carli F, Baldini G, Feldman LS. Redesigning the preoperative clinic: from risk stratification to risk modification. JAMA Surg 2021; 156: 191–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.5550

Chen CC, Li HC, Liang JT, et al. Effect of a modified hospital elder life program on delirium and length of hospital stay in patients undergoing abdominal surgery. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 827–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.1083

McDonald SR, Heflin MT, Whitson HE, et al. Association of integrated care coordination with postsurgical outcomes in high-risk older adults. JAMA Surg 2018; 153: 454–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513

Harari D, Hopper A, Dhesi J, Babic-Illman G, Lockwood L, Martin F. Proactive care of older people undergoing surgery ('POPS’): designing, embedding, evaluating and funding a comprehensive geriatric assessment service for older elective surgical patients. Age Ageing 2007; 36: 190–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl163

Hall DE, Arya S, Schmid KK, et al. Association of a frailty screening initiative with postoperative survival at 30, 180, and 365 days. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 233–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4219

Deiner S, Fleisher LA, Leung JM, et al. Adherence to recommended practices for perioperative anesthesia care for older adults among US anesthesiologists: results from the ASA Committee on Geriatric Anesthesia-Perioperative Brain Health Initiative ASA member survey. Perioper Med (Lond) 2020; 9: 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-020-0136-9

Eamer G, Gibson JA, Gillis C, et al. Surgical frailty assessment: a missed opportunity. BMC Anesthesiol 2017; 17: 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-017-0390-7

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci 2017; 12: 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, Eccles M. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol 2008; 57: 660–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x

Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23: 334–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4%3C334::aid-nur9%3E3.0.co;2-g

Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010; 33: 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20362

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014; 89: 1245–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000388

Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health 2010; 25: 1229–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015

Mackenzie N, Knipe S. Research dilemmas: paradigms, methods and methodology. Issues Educ Res 2006; 16: 193–205.

Dowling M. Approaches to reflexivity in qualitative research. Nurse Res 2006; 13: 7–21. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2006.04.13.3.7.c5975

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

Patey AM, Islam R, Francis JJ, Bryson GL, Grimshaw JM, Canada PRIME Plus Team. Anesthesiologists’ and surgeons’ perceptions about routine pre-operative testing in low-risk patients: application of the theoretical domains framework (TDF) to identify factors that influence physicians’ decisions to order pre-operative tests. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-52

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005; 15: 1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Thompson C, McCaughan D, Cullum N, Sheldon TA, Raynor P. Increasing the visibility of coding decisions in team-based qualitative research in nursing. Int J Nurs Stud 2004; 41: 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.03.001

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed. London: Sage; 1994.

Islam R, Tinmouth AT, Francis JJ, et al. A cross-country comparison of intensive care physicians’ beliefs about their transfusion behaviour: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci 2012; 7: 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-93

Francis JJ, Stockton C, Eccles MP, et al. Evidence-based selection of theories for designing behaviour change interventions: using methods based on theoretical construct domains to understand clinicians’ blood transfusion behaviour. Br J Health Psychol 2009; 14: 625–46. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910708x397025

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Fourth Generation Evaluation, 1st ed. London: Sage; 1989.

Boland L, Graham ID, Légaré F, et al. Barriers and facilitators of pediatric shared decision-making: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2019; 14: 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0851-5

Davis D, Davis N. Selecting educational interventions for knowledge translation. CMAJ 2010; 182: E89–93. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.081241

Aucoin SD, Hao M, Sohi R, et al. Accuracy and feasibility of clinically applied frailty instruments before surgery. Anesthesiology 2020; 133: 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000003257

The Ottawa Hospital. Clinical frailty scale (CFS) training module. Available from URL: https://rise.articulate.com/share/deb4rT02lvONbq4AfcMNRUudcd6QMts3#/ (accessed June 2022).

Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016; 45: 353–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw039

Alkadri J, Hage D, Nickerson LH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of preoperative frailty instruments derived from electronic health data. Anesth Analg 2021; 133: 1094–1106. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000005595

Presseau J, McCleary N, Lorencatto F, Patey AM, Grimshaw JM, Francis JJ. Action, actor, context, target, time (AACTT): a framework for specifying behaviour. Implement Sci 2019; 14: 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0951-x

Carminati L. Generalizability in qualitative research: a tale of two traditions. Qual Health Res 2018; 28: 2094–2101. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318788379

Author contributions

Emily Hladkowicz, Kristin Dorrance, and Daniel I. McIsaac contributed to study conception, study design, data acquisition, data analysis, and data interpretation and drafted, revised, and approved the final manuscript. Daniel I. McIsaac is the guarantor. Gregory L. Bryson, Sylvain Gagne, Allen Huang, Luke T. Lavallée, and Hussein Moloo contributed to study conception, study design, and data interpretation and revised and approved the final manuscript. Alan Forster and Manoj M. Lalu contributed to study conception, study design, and data interpretation and drafted, revised, and approved the final manuscript. Janet Squires contributed to study conception, study design, data analysis, and data interpretation and drafted, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts or disclosures.

Funding statement

This project was funded by the University of Ottawa Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine (Ottawa, ON, Canada).

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Stephan K. W. Schwarz, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hladkowicz, E., Dorrance, K., Bryson, G.L. et al. Identifying barriers and facilitators to routine preoperative frailty assessment: a qualitative interview study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 1375–1389 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02298-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02298-x