Abstract

Background

Cancer survivorship care is traditionally performed in secondary care. Primary care is often involved in cancer management and could therefore play a more prominent role.

Purpose

To assess outcomes of cancer survivorship care in primary versus secondary care.

Methods

A systematic search of MEDLINE and EMBASE was performed. All original studies on cancer survivorship care in primary versus secondary care were included. A narrative synthesis was used for three distinctive outcomes: (1) clinical, (2) patient-reported, and (3) costs.

Results

Sixteen studies were included: 7 randomized trials and 9 observational studies. Meta-analyses were not feasible due to heterogeneity. Most studies reported on solid tumors, like breast (N = 7) and colorectal cancers (N = 3). Clinical outcomes were reported by 10 studies, patient-reported by 11, and costs by 4. No important differences were found on clinical and patient-reported outcomes when comparing primary- with secondary-based care. Some differences were seen relating to the content and quality of survivorship care, such as guideline adherence and follow-up tests, but there was no favorite strategy. Survivorship care in primary care was associated with lower societal costs.

Conclusions

Overall, cancer survivorship care in primary care had similar effects on clinical and patient-reported outcomes compared with secondary care, while resulting in lower costs.

Implications for cancer survivors

Survivorship care in primary care seems feasible. However, since the design and outcomes of studies differed, conclusive evidence for the equivalence of survivorship care in primary care is still lacking. Ongoing studies will help provide better insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

To date, the number of patients with incident cancer and cancer survivors is increasing, due to an aging population and the improvements in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Cancer survival has increased to over 60% between 2010 and 2020, as previously predicted by The Dutch Cancer Society [1]. In numerous countries worldwide, including the Netherlands, patients treated for cancer are initially included in a secondary care–based follow-up program, mainly focusing on the early detection of recurrences and treatment of symptoms caused by the cancer or its treatment. However, survivorship care for cancer encompasses not only detection of recurrences but also the attention to rehabilitation (psychological and social support, integration in society and secondary prevention) as addressed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) back in 2006 [2].

Following completion of cancer treatment, many patients experience unmet needs and symptoms [3] and primary care is often involved in management of these needs and symptoms, especially for the older population with comorbidities [4,5,6,7,8,9]. A more general approach is therefore likely to be favorable to patient outcomes [10]. Traditional core values of primary care, such as the continuity and coordination of care, can lend themselves for the improvement of cancer survivorship, but the role of primary care may vary depending on context and setting [10, 11].

Several reviews have been published on alternative survivorship care strategies, such as GP-, PCP-, nurse-led, patient-initiated, and shared care [12,13,14,15,16]. However, none have focused exclusively on survivorship care by physicians working in primary care. The aim of this systematic review is to provide an overview of the outcomes of survivorship care in primary- compared with secondary-based care.

Methods

Study design and search strategy

In February 2020, a systematic search was performed in MEDLINE and EMBASE to identify original studies on cancer survivorship care. General terms for survivorship care, including follow-up and aftercare, were used. In addition to the MEDLINE and EMBASE search, reference checking was performed to identify possible other relevant publications. (See Appendix 1 for the search strategy.)

Eligibility, selection, and data extraction

Original studies comparing cancer survivorship care in primary to secondary-based care were included. As health care systems differ around the globe, generalist professions providing primary- or community-based care, such as a general practitioner (GP), primary care physicians (PCPs), and family physicians (FPs), were included in this review. Studies reporting on patients of any age who were (curatively) treated for any type or stage of cancer were eligible. No restrictions were made on the type of outcomes. Economic evaluations of cancer survivorship care programs were also considered for inclusion. Studies on shared care and patient or physician preferences for survivorship care were excluded from this review.

All studies were screened on title and abstract by two independent researchers (JV and TW). Subsequently, complete texts were read to ensure inclusion criteria, and data were extracted. Data extraction was performed by one researcher (JV) based on a predefined data format. Disagreement between the two researchers on study selection and data extraction was resolved by discussion or, if necessary, by consulting a third independent researcher (KvA).

Data analysis

As we intended a broad and conclusive review, no restrictions were made on the type of patient, outcomes, or methodology, which resulted in substantial heterogeneity of studies. Therefore, meta-analyses were not feasible and a narrative synthesis was used.

Outcomes were grouped into three distinctive categories: (1) clinical outcomes as measured by medical records (including survival, serious clinical events, and documented follow-up care), (2) patient-reported outcomes as measured by patient questionnaires and interviews (including quality of life, symptoms, patient satisfaction, and self-reported receipt of survivorship care), and (3) costs of survivorship care programs (including societal and patient costs).

Quality assessment

A risk of bias analysis was performed for all included studies according to the designated quality assessment tools as advised by the Cochrane collaboration. The consort instrument was used for randomized clinical trials [17], and the ROBINS-I for (non-randomized) observational studies [18].

Results

Study selection

The systematic search retrieved 1766 original studies (Fig. 1). Reference checking did not identify any additional studies. After title and abstract screening, full text of 42 studies was reviewed. Based on the predefined eligibility criteria, 16 studies were included in this review. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias assessment revealed low risk of bias in 10 studies, intermediate in 3, and high risk of bias in 3 out of 16 studies (see Appendix Table 5). Risk of bias was often inherent to the design of the study, including selection, misclassification, recall, and interviewer bias.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the included studies. Seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this review [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Three studies of Grunfeld et al. were based on the same RCT, but reported on separate outcomes [20,21,22]. Other included studies were based on a type of observational study [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Most studies reported on patients with solid tumors, such as breast and colorectal cancers. The number of patients ranged from 98 in a retrospective cohort study [26] to 5009 in a quasi-experimental observational study [29]. Six studies reported on physicians working in primary care, of which two studies did not further specify the provider type [31, 32]. The length of follow-up ranged from 1 to 15 years.

Clinical outcomes

Ten studies reported on clinical outcomes (see Table 2). No important differences were seen in survival between follow-up strategies after 3 up to 15 years of follow-up [30, 33, 34]. Follow-up in secondary care was associated with shorter relapse-free survival (RFS) and higher likelihood of receiving palliative treatment with chemotherapy (58% versus 34%, p = 0.03) in pancreatic cancer patients in a cohort study, in part because patients in secondary care had more advanced primary tumors [33]. Eight studies examined the occurrence of serious clinical events. No differences were seen relating to the number (and time of diagnosis) of recurrences and metastases [19, 20, 23,24,25,26], deaths [23, 25, 29], or other clinical events [23, 24, 26] between primary and secondary care–based follow-up.

Documented follow-up care, as measured by adherence to medical guidelines and follow-up tests, was assessed by two RCT’s. Murchie et al. [24] found that 98.1% of patients in primary-based care were seen according to guidelines versus 80.9% of patients in secondary-based care (p = 0.020). In the second study, patients in primary care were more likely to have one or more fecal blood tests (rate ratio 2.4, CI 1.4–4.44, p = 0.003), whereas patients in secondary care were more likely to have ultrasounds and colonoscopies, although it remained unclear whether or not this was done in accordance with follow-up guidelines [25].

Patient-reported outcomes

Eleven studies, including all six RCTs, measured patient-reported outcomes (see Table 3). After adjustment for clinical and pathological covariates, no differences were seen in overall quality of life (QoL) and anxiety and depression between survivorship care strategies [19, 20, 23,24,25,26]. One observational study examined other bothersome symptoms, showing less fatigue among breast cancer patients in primary care (62.0% versus 81.1%, p = 0.005) [31].

High levels of patient satisfaction and perception of care were found for survivorship care in both primary- and secondary-based care [22, 24,25,26,27, 32]. Using an adapted validated questionnaire, higher levels of patient satisfaction were found in primary care–based groups in two RCTs (9 out of 15 aspects by Grunfeld et al. [22] and 6 out of 15 by Murchie et al. [24]). In contrast, a questionnaire administered in an observational study [26] showed greater satisfaction in all 6 dimensions for breast cancer patients in secondary-based care (p < 0.05).

Five observational studies examined self-reported receipt of survivorship care by means of questionnaires and interviews. Disparate results were seen among primary- and secondary-based care, but there was no evidence for a more favorable strategy based on these results. Two studies showed a lower adherence to recommended periodic clinical examinations for breast cancer patients by physicians working in primary care (approximately 80% versus 90% in secondary care, p < 0.05) [31, 32]. In another study, patients in primary care were more likely to receive examination as is recommended by national guidelines (58% versus 36%, p = 0.004) [27]. No differences were seen in patient self-reported mammogram frequency [28, 31, 32]. Maly et al. [28] found a higher uptake of preventive tests, including Pap smear (AOR 2.90, CI 1.05–8.04, p = 0.040) and colonoscopy (AOR 2.99, CI 1.5–8.51, p = 0.041), among underserved breast cancer patients in primary care. Physicians in primary care helped more often with lifestyle improvements for colorectal cancer patients [27], but this was not the case among breast cancer patients [31].

Costs

Survivorship care in primary care was associated with lower societal and patient costs in all four studies that performed cost analyses (see Table 4) [19, 21, 26, 29]. The main cost driver in all studies was the mean cost per visit, including organizational and physician costs.

Discussion

In this review, similar effects on clinical and patient-reported outcomes were seen for survivorship care in primary- compared with secondary-based care. Although the evidence should be interpreted with caution, survivorship care in primary care seems feasible and results in lower costs.

Comparison with existing literature

A recent Cochrane review found little to no effects on pre-defined outcomes for RCTs comparing non-specialist (e.g., PCP-led, nurse-led, patient-initiated, and shared care) to specialist-led follow-up [12]. The certainty of evidence was generally low due to the limited amount of RCTs. Similarly to the Cochrane review, this review found no important differences in survivorship care between primary and secondary care relating to clinical (survival and recurrences) and patient-reported outcomes (quality of life and symptoms).

This review has identified additional outcomes in comparison with the Cochrane review relating to the content and quality of survivorship care. The content of survivorship care is examined by both documented follow-up care and self-reported receipt of survivorship care. Some differences were seen in these outcomes, especially relating to the adherence to guidelines and follow-up tests, but the results showed no favorite strategy. It remains unclear whether or not these differences may affect other outcomes, such as detection of recurrences and survival. Showing differences in these types of outcomes requires great numbers of patients and considerable follow-up time among often older patients with comorbidities, making this a challenging undertaking.

This review has examined patient’s perceptions and satisfaction with care as indicators for the quality of survivorship care. High levels of quality of care were found for survivorship care in both primary- and secondary-based care. Two out of three RCTs showed higher levels of patient satisfaction with primary-based care, illustrating its feasibility [22, 24]. The aggregation of these results provides us with the indication that survivorship care in primary care is similar to care by a specialist. Moreover, survivorship care in primary care led to lower costs in all studies that performed cost-analyses.

Strengths and limitations

Our review provides additional evidence to previous literature by focusing exclusively on survivorship care by physicians working in primary care and by including non-randomized studies in the results. By performing a non-restrictive search and selection strategy, two additional outcomes relating to the content and quality of survivorship care have been identified in comparison with the recent Cochrane review. The search strategy, including reference checking, provides a sensitive search result.

There are some limitations that need to be addressed. Inherent to the design of some studies, differences were seen in baseline characteristics. Older patients and patients with prognostic better disease stage were sometimes more likely to receive follow-up in primary care [26, 27, 30,31,32,33,34]. Despite adjusting for covariates, these differences might have influenced outcomes. Due to the substantial heterogeneity in outcomes and methodology, no data could be pooled for meta-analyses, hampering the interpretation of results. However, using a narrative synthesis, no important differences were seen relating to clinical and patient-reported outcomes. These results are in line with previous reviews [12,13,14,15,16].

Implications for future practice and research

As the number of cancer survivors is rapidly increasing and resources are limited [12,13,14,15,16], alternative survivorship care strategies for the hospital-based survivorship care are deemed desirable. This review showed that cancer survivorship care in primary care seems feasible and worthwhile to consider. However, the role and capacity of physicians in primary care can vary depending on context and setting [10, 11]. Most studies were performed in the UK and Canada in which physicians work as gate-keepers to secondary health care services. In these countries, a publicly funded universal health care system is in place. Other studies were performed in countries such as the US and Spain in which the health care system is both publicly and privately funded, and the role of primary care could be less distinguished. The randomized trials that could be identified, were limited to countries with a universal health care system, so further research is warranted to evaluate whether the results of these trials are also applicable to other health care systems. Furthermore, both clinical and patient-reported outcomes might change over time and could be affected by the length of follow-up. Therefore, to assess durable effects of survivorship care, greater number of patients and considerable follow-up time in these trials would be preferable. Moreover, the impact on the work-load for primary care physicians needs to be evaluated in case of growing numbers of patients in primary care–based cancer survivorship care.

Conclusion

This review presents a comprehensive overview of survivorship care in primary care. To our opinion, this review has underlined the feasibility of survivorship care in primary care or possibility of some form of cooperative care. However, delivering high-quality survivorship care will also put restraints on primary care. This requires not only sufficient funding but also investments in organization and staff. Further studies with adequate designs are needed.

References

Knottnerus JA, Wijffels JF. SCK of KWF Kankerbestrijding. Aftercare in cancer: the role of primary care. Dutch Cancer Society’s Signalling Committee on Cancer. 2011.

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer patient to Cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Aziz NM. Cancer survivorship research: state of knowledge, challenges and opportunities. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden). 2007;46(4):417–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/02841860701367878.

Khan NF, Watson E, Rose PW. Primary care consultation behaviours of long-term, adult survivors of cancer in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(584):197–9. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X561195.

Fidjeland HL, Vistad I, Gjelstad S, Brekke M. Exploring why patients with cancer consult GPs: a 1-year data extraction. BJGP open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen19X101663.

Duineveld LA, Molthof H, Wieldraaijer T, van de Ven AW, Busschers WB, van Weert HC, et al. General practitioners’ involvement during survivorship care of colon cancer in the Netherlands: primary health care utilization during survivorship care of colon cancer, a prospective multicentre cohort study. Fam Pract. 2019;36:765–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmz028.

Brandenbarg D, Roorda C, Groenhof F, de Bock GH, Berger MY, Berendsen AJ. Primary healthcare use during follow-up after curative treatment for colorectal cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2017;26(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12581.

Demagny L, Holtedahl K, Bachimont J, Thorsen T, Letourmy A, Bungener M. General practitioners’ role in cancer care: a French-Norwegian study. BMC Research Notes. 2009;2:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-2-200.

Kenzik KM. Health care use during cancer survivorship: review of 5 years of evidence. Cancer. 2019;125(5):673–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31852.

Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, Dommett R, Earle C, Emery J, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(12):1231–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00205-3.

Adam R, Watson E. The role of primary care in supporting patients living with and beyond cancer. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2018;12(3):261–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/spc.0000000000000369.

Hoeg BL, Bidstrup PE, Karlsen RV, Friberg AS, Albieri V, Dalton SO, et al. Follow-up strategies following completion of primary cancer treatment in adult cancer survivors. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;2019(11). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012425.pub2.

Lewis RA, Neal RD, Williams NH, France B, Hendry M, Russell D, et al. Follow-up of cancer in primary care versus secondary care: systematic review. The British Journal of General Practice. 2009;59(564):e234–47. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X453567.

Montgomery DA, Krupa K, Cooke TG. Alternative methods of follow up in breast cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(11):1625–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603771.

Taggart F, Donnelly P, Dunn J. Options for early breast cancer follow-up in primary and secondary care - a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:238. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-238.

Davies NJ, Batehup L. Towards a personalised approach to aftercare: a review of cancer follow-up in the UK. Journal of Cancer Survivorship : Research and Practice. 2011;5(2):142–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-010-0165-3.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2011;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, Savovic J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 2016;355:i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919.

Augestad KM, Norum J, Dehof S, Aspevik R, Ringberg U, Nestvold T, et al. Cost-effectiveness and quality of life in surgeon versus general practitioner-organised colon cancer surveillance: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002391.

Grunfeld E, Mant D, Yudkin P, Adewuyi-Dalton R, Cole D, Stewart J, et al. Routine follow up of breast cancer in primary care: randomised trial. BMJ (Clinical Research ed). 1996;313(7058):665–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.313.7058.665.

Grunfeld E, Gray A, Mant D, Yudkin P, Adewuyi-Dalton R, Coyle D, et al. Follow-up of breast cancer in primary care vs specialist care: results of an economic evaluation. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(7–8):1227–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6690197.

Grunfeld E, Fitzpatrick R, Mant D, Yudkin P, Adewuyi-Dalton R, Stewart J, et al. Comparison of breast cancer patient satisfaction with follow-up in primary care versus specialist care: results from a randomized controlled trial. The British Journal of General Practice. 1999;49(446):705–10.

Grunfeld E, Levine MN, Julian JA, Coyle D, Szechtman B, Mirsky D, et al. Randomized trial of long-term follow-up for early-stage breast cancer: a comparison of family physician versus specialist care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(6):848–55. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2005.03.2235.

Murchie P, Nicolson MC, Hannaford PC, Raja EA, Lee AJ, Campbell NC. Patient satisfaction with GP-led melanoma follow-up: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(10):1447–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605638.

Wattchow DA, Weller DP, Esterman A, Pilotto LS, McGorm K, Hammett Z, et al. General practice vs surgical-based follow-up for patients with colon cancer: randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(8):1116–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603052.

Baena-Canada JM, Ramirez-Daffos P, Cortes-Carmona C, Rosado-Varela P, Nieto-Vera J, Benitez-Rodriguez E. Follow-up of long-term survivors of breast cancer in primary care versus specialist attention. Fam Pract. 2013;30(5):525–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmt030.

Haggstrom DA, Arora NK, Helft P, Clayman ML, Oakley-Girvan I. Follow-up care delivery among colorectal cancer survivors most often seen by primary and subspecialty care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S472–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1017-6.

Maly RC, Liu Y, Diamant AL, Thind A. The impact of primary care physicians on follow-up care of underserved breast cancer survivors. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2013;26(6):628–36. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.120345.

Mittmann N, Beglaryan H, Liu N, Seung SJ, Rahman F, Gilbert J, et al. Examination of health system resources and costs associated with transitioning cancer survivors to primary care: a propensity-score-matched cohort study. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.18.00275.

Parry HM, Damery S, Mudondo NP, Hazlewood P, McSkeane T, Aung S, et al. Primary care management of early stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is safe and effective. QJM. 2015;108(10):789–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcv017.

Railton C, Lupichuk S, McCormick J, Zhong L, Ko JJ, Walley B, et al. Discharge to primary care for survivorship follow-up: how are patients with early-stage breast cancer faring? Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2015;13(6):762–71. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2015.0091.

Risendal BC, Sedjo RL, Giuliano AR, Vadaparampil S, Jacobsen PB, Kilbourn K, et al. Surveillance and beliefs about follow-up care among long-term breast cancer survivors: a comparison of primary care and oncology providers. Journal of Cancer Survivorship : Research and Practice. 2016;10(1):96–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0454-y.

Samawi HH, Yin Y, Lim HJ, Cheung WY. Primary care versus oncology-based surveillance following adjuvant chemotherapy in resected pancreatic cancer. Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer. 2018;49(4):429–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-017-9988-8.

Peixoto RD, Lim HJ, Kim H, et al. Patterns of surveillance following curative intent therapy for gastroesophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Canc. 2014;45:325–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-014-9601-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception. The literature search was performed by J.A.M. Vos in collaboration with a medical librarian (F. van Etten-Jamaludin) of the Amsterdam UMC. Data selection and analysis were performed by J.A.M. Vos, T. Wieldraaijer and K.M. van Asselt. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.A.M. Vos. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

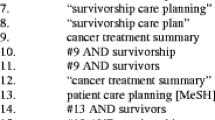

Appendix 1. Search strategy

The following search strategy was used in MEDLINE. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a medical librarian (FvE) of the Amsterdam UMC, location AMC. A total of 1766 studies were found from inception up to the 22nd of February of 2020.

History | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Search | Add to builder | Query | Items found | Time |

#5 | Add | Search ((((#1) AND #2) AND #3) AND #4 Sort by: Publication Date | 1385 | 09:49:37 |

#4 | Add | Search (“Cohort Studies”[Mesh] OR “Aftercare”[Mesh] OR follow-up*[tiab] OR followup*[tiab] OR aftercare[tiab] OR after-care[tiab] OR surveillance*[tiab] OR post-operat*[tiab] OR postoperat*[tiab] OR post-surg*[tiab] OR postsurg*[tiab] OR post-treatment*[tiab] OR posttreatment*[tiab] OR checkup*[tiab OR check up*[tiab]) Sort by: PublicationDate | 3096777 | 09:49:12 |

#3 | Add | Search (“Secondary Care”[Mesh] OR “Secondary Prevention”[Mesh] OR dermatologist*[tiab] OR oncologist*[tiab] OR surgeon*[tiab] OR gastroenterologist*[tiab] OR urologist*[tiab] OR specialistled[tiab] OR secondary care[tiab] OR secondary healthcare[tiab] OR secondary health care[tiab] OR hospital care[tiab] OR hospital follow up[tiab] OR hospital-based follow-up[tiab] OR cancer center*[tiab] OR specialist care[tiab]) Sort by: PublicationDate | 290700 | 09:48:59 |

#2 | Add | Search (“Family Practice”[Mesh] OR “Primary Health Care”[Mesh] OR “Physicians, Primary Care”[Mesh] OR “Physicians, Family”[Mesh] OR “General Practitioners”[Mesh] OR “General Practice”[Mesh] OR family practi*[tiab] OR family care*[tiab] OR family healthcare*[tiab] OR family health care*[tiab] OR primary care*[tiab] OR primary healthcare*[tiab] OR primary health care*[tiab] OR general practi*[tiab] OR GP[tiab] OR GPs[tiab] OR PCP[tiab] OR PCPs[tiab] OR family doctor*[tiab] OR family physician*[tiab]) Sort by: PublicationDate | 404255 | 09:48:49 |

#1 | Add | Search (“Neoplasms”[Mesh] OR “Cancer Survivors”[Mesh] OR neoplasms*[tiab] OR cancer*[tiab] OR tumor*[tiab] OR tumour*[tiab] OR malignan*[tiab]) Sort by: PublicationDate | 4174383 | 09:48:35 |

# | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

1 | exp Neoplasms/ or Cancer Survivors/ or (neoplasm* or cancer* or tumor* or tumor* or malignan*).ti,ab,kw. | 5,705,657 |

2 | general practice/ or general practitioner/ or exp. primary health care/ or (family practi* or family care* or family healthcare* or family health care* or primary care* or primary healthcare* or primary health care* or general practi* or GP or GPs or PCP or PCPs or family doctor* or family physician*).ti,ab,kw. | 469,424 |

3 | exp secondary health care/ or (dermatologist* or oncologist* or surgeon* or gastroenterologist* or urologist* or specialist led or secondary care or secondary healthcare or secondary health care or hospital care or cancer center* or specialist care or hospital follow up or hospital-based follow-up).ti,ab,kw. | 45,998 |

4 | cohort analysis/ or exp. aftercare/ or (follow-up* or followup* or aftercare or after-care or surveillance* or post-operat* or postoperat* or post-surg* or postsurg* or post-treatment* or posttreatment* or checkup* or check up*).ti,ab,kw. | 3,217,165 |

5 | 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 | 1965 |

6 | limit 5 to conference abstract status | 932 |

7 | 5 not 6 | 1104 |

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vos, J.A.M., Wieldraaijer, T., van Weert, H.C.P.M. et al. Survivorship care for cancer patients in primary versus secondary care: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 15, 66–76 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00911-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00911-w