Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the present study is to determine predictors of attendance at a network of publicly funded specialized survivor clinics by a population-based cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study linking data on eligible patients identified in a provincial pediatric cancer registry with health administrative databases to determine attendance at five specialized survivor clinics in the Canadian province of Ontario between 1999 and 2012. Eligible survivors were treated for cancer at ≤18 years between 1986 and 2005, had survived ≥5 years from their most recent pediatric cancer event, and contributed ≥1 year of follow-up after age 18 years. We assessed the impact of cancer type, treatment intensity, cumulative chemotherapy doses, radiation, socioeconomic status, distance to nearest clinic, and care from a primary care physician (PCP) on attendance using recurrent event multivariable regression.

Results

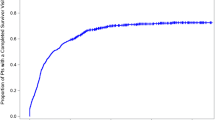

Of 7482 children and adolescents treated for cancer over the study period, 3972 were eligible for study inclusion, of which 3912 successfully linked to administrative health data. After a median of 7.8 years (range 0.2–14.0) of follow-up, 1695/3912 (43.3 %) had attended at least one adult survivor clinic visit. Significantly increased rates of attendance were associated with female gender, higher treatment intensity, radiation, higher alkylating agent exposure, higher socioeconomic status, and an annual exam by a PCP. Distance significantly impacted attendance with survivors living >50 km away less likely to attend than those living within 10 km (relative rate 0.77, p = 0.003).

Conclusion

Despite free access to survivor clinics, the majority of adult survivors of childhood cancer do not attend.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Alternate models of care need to be developed and assessed, particularly for survivors living far from a specialized clinic and those at lower risk of developing late effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Phillips SM et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(4):653–63.

Hudson MM et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2371–81.

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2005.

Wallace WH et al. Developing strategies for long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer. BMJ. 2001;323(7307):271–4.

Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–24.

Blaauwbroek R et al. Shared care by paediatric oncologists and family doctors for long-term follow-up of adult childhood cancer survivors: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):232–8.

Kazak AE et al. A revision of the intensity of treatment rating scale: classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(1):96–9.

Green DM et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(1):53–67.

Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent and young adult cancers, Version 4.0. Monrovia, CA: Children’s Oncology Group; 2013.

Pilote L et al. Universal health insurance coverage does not eliminate inequities in access to cardiac procedures after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2003;146(6):1030–7.

Ballantyne M et al. Maternal and infant predictors of attendance at neonatal follow-up programmes. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(2):250–8.

Matheson FI et al. Development of the Canadian Marginalization Index: a new tool for the study of inequality. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(8 Suppl 2):S12–6.

Cook RJ, Lawless JF. Analysis of repeated events. Stat Methods Med Res. 2002;11(2):141–66.

Twisk JW, Smidt N, de Vente W. Applied analysis of recurrent events: a practical overview. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):706–10.

Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Statistics for biology and health. New York: Springer; 2000. xiii, 350 p.

Guo Z, Gill TM, Allore HG. Modeling repeated time-to-event health conditions with discontinuous risk intervals. An example of a longitudinal study of functional disability among older persons. Methods Inf Med. 2008;47(2):107–16.

Lawless JF, Nadeau C. Some simple robust methods for the analysis of recurrent events. Technometrics. 1995;37(2):158–68.

Park ER, et al. Childhood cancer survivor study participants’ perceptions and understanding of the affordable care act. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(7):764–72.

Oeffinger KC, et al. Models of cancer survivorship health care: moving forward. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2014; 205–13.

McCabe MS et al. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40(6):804–12.

Zheng DJ, et al. Patterns and predictors of survivorship clinic attendance in a population-based sample of pediatric and young adult childhood cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015. doi:10.1007/s11764-015-0493-4.

Nathan PC, et al. Family physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):275–82.

Suh E et al. General internists’ preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):11–7.

Nathan PC et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4401–9.

Eshelman-Kent D et al. Cancer survivorship practices, services, and delivery: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) nursing discipline, adolescent/young adult, and late effects committees. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):345–57.

Ristovski-Slijepcevic S et al. A cross-Canada survey of clinical programs for the care of survivors of cancer in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Child Health. 2009;14(6):375–8.

Essig S et al. Follow-up programs for childhood cancer survivors in Europe: a questionnaire survey. PLoS One. 2012;7(12), e53201.

Blaauwbroek R et al. Family doctor-driven follow-up for adult childhood cancer survivors supported by a web-based survivor care plan. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(2):163–71.

Bertakis KD et al. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(2):147–52.

Kadan-Lottick NS et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2002;287(14):1832–9.

Cherven B et al. Knowledge and risk perception of late effects among childhood cancer survivors and parents before and after visiting a childhood cancer survivor clinic. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2014;31(6):339–49.

Stricker CT, O’Brien M. Implementing the commission on cancer standards for survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(Suppl):15–22.

Hudson MM et al. Increasing cardiomyopathy screening in at-risk adult survivors of pediatric malignancies: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(35):3974–81.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Pediatric Oncology Group of Ontario through funding provided by the Canadian Cancer Society, Ontario Division. Astrid Guttmann receives salary funding through a CIHR Applied Research Chair in Child Health Services Research. This study was also supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Conflict of interest

Paul Nathan, Mohammad Agha, Jason Pole, Rinku Sutradhar, Astrid Guttmann, David Hodgson, and Mark Greenberg all declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Boards at all five pediatric cancer centers in the province of Ontario. Since the study involved database/registry research only and no patients were contacted as part of the study procedure, the ethics boards waived the need for informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nathan, P.C., Agha, M., Pole, J.D. et al. Predictors of attendance at specialized survivor clinics in a population-based cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv 10, 611–618 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0522-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0522-y