Abstract

Background

Ward rounds are important for communicating with patients, but it is unclear whether bedside or non-bedside case presentation is the better approach.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search up to July 2018 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing bedside and non-bedside case presentations. Data was abstracted independently by two researchers and study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Our primary outcome was patient’s satisfaction with ward rounds. Our main secondary outcome was patient’s understanding of disease and the management plan.

Results

Among 1647 identified articles, we included five RCTs involving 655 participants with overall moderate trial quality. We found no difference in having low patient’s satisfaction between bedside and non-bedside case presentations (risk ratio [RR], 0.85; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.09). We also found no impact on patient’s understanding of their disease and management plan (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.67 to 1.28). Trial sequential analysis (TSA) indicated low power of our main analysis.

Discussion

We found no differences in patient-relevant outcomes between bedside and non-bedside case presentations with a lack of statistical power among current trials. There is a need for larger studies to find the optimal approach to patient case presentation during ward rounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Patient-centered medicine is an important tenant for modern inpatient care. The Institute of Medicine defines patient-centered care as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions” 1 (also see2,3). During hospitalizations, a common time for interaction between patients and their medical team is during ward rounds. Usually, junior physicians present a patient’s case to senior physicians followed by an academic discussion.

Patient case presentations can take place at the bedside or in other settings. While bedside presentations may facilitate patient involvement in management decisions, there is concern that patients may be overwhelmed by the complexity of medical information presented. In a recent study,4 psychology students only recalled about 7 out of 28 items of information presented in a video of an emergency department discharge. A study examining the recall of preoperative discussion in patients undergoing neurosurgery found low rates of patient recall of surgical risk 2 hours after presentation.5 Accordingly, patients’ comprehension and recall of medical information is limited after bedside presentations.

Alternatively, patient case presentation can take place in other settings (in conference rooms or just outside the patient’s room). The treating team subsequently enters the room and gives the patient a summary of the medical situation, completes medical information as needed, and discusses next steps. This approach may be less confusing, but there is also less active patient involvement in the medical discussions, which might negatively influence patients’ perception of the care provided.6

The optimal approach to patient case presentation during ward rounds remains unclear. The decision of bedside or non-bedside case presentations is not evidence-based but depends on the preference of the medical team, local traditions, or facilities. To inform medical educators on best practice, we performed a systematic review. Our meta-analysis focuses on patient’s satisfaction with ward rounds and understanding of their disease and the management plan, important components of patient-centered care.

METHODS

We followed PRISMA guidelines in conducting this systematic review.7

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, PsychINFO, and CINHAL, through July 2018, last searched on 23 July 2018 using a strategy that included input from a medical librarian experienced in systematic reviews. The search strategy for each database is given in Appendix. To identify additional published, unpublished, and ongoing studies, we (1) tracked relevant references through Web of Science’s and PubMed’s cited reference search, (2) applied the similar-articles-search of PubMed, and (3) scanned the reference lists of identified studies.

Study Selection for Review

We included randomized controlled trials of articles that involved adult, non-psychiatric, and medical inpatients and compared bedside to non-bedside rounds. In addition, studies had to include some measure of the intervention’s impact on patient- or provider-relevant outcomes or quality of care, particularly patient’s satisfaction and patient’s understanding of disease and the management plan. We excluded studies involving patients suffering from deliria or dementia.

Two researcher (M.G., C.B.) screened the titles and abstracts of articles for eligibility. We obtained the full texts of studies considered eligible from this process or for which eligibility was unclear. Two researcher (M.G., C.B.) independently decided on each trial’s inclusion or exclusion in the review. They resolved any disagreements by discussion, and when consensus could not be reached, another author (S.H.) was consulted for a final decision.

Outcome Measures

The primary endpoint was low patient’s satisfaction with ward rounds. Secondary endpoints were low patient’s understanding of disease and the management plan reported by the patients defined as clarity of information shared by the treating team that might facilitate or impede patient’s understanding and all other patient- and provider-related outcomes. Specifically, a total of nine additional patient-relevant outcomes were investigated: patients’ affective reactions to ward round, patients’ perceived involvement in decision-making, patients’ perceived role in decision-making, concordance between experienced and preferred role in decision-making, patient activation, perceived time physicians spent with the patients, perceived physicians’ interpersonal behavior displayed towards the patients, perceived teamwork of the medical team, and trust in the medical team. In addition, two provider-relevant outcomes were examined: preference for bedside or non-bedside case presentation and perceived improvements through bedside patient case presentation. Tables 1 and 2 summarizes the patient- and provider-relevant outcomes investigated respectively as reported in the original publications.

Data Extraction, Assessment of Methodological Quality, and Study Selection for Meta-analysis

Data was abstracted independently by two authors (M.G., S.H.) and study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (http://methods.cochrane.org/bias/assessing-risk-bias-included-studies).

Data Analysis

We expressed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We expressed continuous data as the mean differences. Data were pooled using a random effects model. Heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by the Q statistic (considered significant for p values <.10) and H, R, and I statistics. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 12.1 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

To determine whether cumulative sample size was powered for the obtained effect and to avoid random error, we also used trial sequential analysis (TSA) using TSA version 0.9.5.10 Beta (TSA 2016; www.ctu.dk/tsa).

RESULTS

Studies Identified

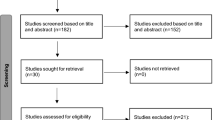

After removal of duplicates, our search retrieved 1647 records potentially eligible for this analysis. After excluding studies by examining title and abstract, five full-text articles were screened and classified eligible for inclusion (see Fig. 1).

Description of Studies

Study dates ranged from 19978 to 20169 and originated from three countries: three from the USA,8,9,10 one from Japan,11 and one from South Africa.12 A total of 655 participants were involved, with study sample sizes ranging from 5611 to 236.10 Three studies assessed perceptions and preferences of physician (n = 73) and nurse (n = 28) participants.10,11,12

In addition to our primary and secondary outcome, other outcomes assessed included patients’ affective reactions to the ward round,8,11 patients’ perceived involvement in decision-making,9,10 patients’ perceived role in decision-making,10 concordance between experienced and preferred role in decision-making,10 patient activation,10 perceived time physicians spent with the patients,8,9 perceived physicians’ interpersonal behavior displayed towards the patients,8,9,10 perceived teamwork of the medical team,10 and trust in the medical team.9 In addition, two provider-relevant outcomes were examined: preference for bedside or outside the room case presentation11,12 and perceived improvements through bedside patient case presentation 10 (see also Tables 1 and 2).

Studies used mainly dichotomous outcome formats to assess effects of bedside compared to non-bedside case presentations. Ramirez et al.9 also partially applied a 5-point scale (1 “none” to 5 “very much”). O’Leary and colleagues10 used additionally validated measures such as the Degner Control Preference Scale13 involving participants to make a series of paired comparisons of a total of five communication cards as well as the short form of the Patient Activation Measure14 adding up to a score with a theoretical range from 0 to 100. All studies used either structured questionnaires or interviews for data collection (see Table 3).

Quantitative Analysis

Primary Endpoint: Low patient’s Satisfaction with Ward Rounds

All five studies assessed patient’s satisfaction with ward rounds. Four studies dichotomized satisfaction into high and low satisfaction while the fifth measured satisfaction in a linear format. There was no difference in the risk of low patient’s satisfaction with ward rounds (RR, 0.85; 95% CI; 0.66 to 1.09; I2 = 65.6%) (Fig. 2).

To understand whether this non-significant result is due to insufficient power and to estimate needed trial sample sizes, we performed a TSA. As demonstrated in Figure 3, the required sample size for detecting a 25% relative risk reduction would be 5286 patients, but currently, there are only 674 patients included in the 4 trials. These results suggest that for an effect size of 25% relative risk reduction, the four included trials only have about 10% of the required sample size demonstrating strong lack of power regarding the primary endpoint.

TSA analysis regarding the primary endpoint (risk for low satisfaction). The figure shows results of TSA analysis with use of the O’Brien-Fleming boundaries. Using a random effects model and the model variance-based diversity adjustment of the required information size for detecting a 25% relative risk reduction and an alpha error of 5% and a beta error of 20% (80% power) the required information size is 5286.

Secondary Endpoints

Low Patient’s Understanding of Disease and the Management Plan

Similarly, there was no evidence for a difference between bedside and outside patient case presentation regarding low patient’s understanding of disease and the management plan (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.67 to 1.28; I2 = 52.3%).

Other Patient-Relevant Outcomes

The remaining patient-relevant outcomes (for an overview, see Table 1) were not reported in all trials and had great heterogeneity making pooling impossible. Most comparisons found no difference between bedside and non-bedside rounds on several outcomes (Table 1). Lehmann et al.8 and Seo et al.11 found no difference in patients’ affective reactions to the ward round; Ramirez et al.9 and O’Leary et al.10 found no difference in patients’ perceived involvement in decision-making; O’Leary et al.10 found no difference in patients’ perceived role in decision-making, concordance between their experienced and preferred role in decision-making, patient activation, and the perceived teamwork within the medical team; finally, Ramirez et al.9 found no difference in the satisfaction with care and regarding the trust in the medical team.

A handful of outcomes was found to be improved by bedside rounds. Lehman et al.8 found that patients with bedside presentation reported that doctors spent more time (mean, SD) with them (10 (± 6) vs. 6 (± 5) min, p < .001). Yet, there was no difference in the perceived adequacy of time doctors spent with the patient by a second study.9 While two studies found no difference in perceived physicians’ interpersonal behavior displayed towards the patients,8,10 Ramirez et al.9 found that bedside presentation increased the patients’ feeling that the medical team behaved compassionately towards them (p = .03).9

Provider-Relevant Outcomes

Three studies assessed physicians’ and nurses’ preferences and perceptions (Table 2 and 3). In one trial, most (95%) of the junior physicians preferred non-bedside patient case presentation.11 In contrast, Chauke and Pattinson12 found that all interviewed senior (n = 5) and junior physicians (n = 10) preferred bedside presentations, as they felt that physical signs that might have been missed by the examining physician could be picked up by the senior staff. In addition, they felt that bedside presentations provided senior physicians with a platform to teach and perform clinical examinations at the bedside. This allows physicians to get a better overall picture of the patient. Finally, O’Leary and colleagues10 reported mixed findings on the health care teams’ perceived improvements of bedside patient case presentations. Specifically, 47% of physicians and advanced practice providers indicated that bedside rounds improved communication with patients and 37% agreed that bedside rounds improved the efficiency of their workday. Interestingly, even though inferential statistics are not provided, nurses’ perceptions descriptively differed from physicians’ perceptions: improvement in communication with patients was stated by 79% of the nurses, and improvement in the efficiency of their workday by 46%. Taken together, results on the physician and nursing teams’ perceptions of bedside compared to non-bedside patient case presentation were inconsistent across studies. In addition, findings suggest, that perceptions might differ depending on medical function and hierarchy.

DISCUSSION

Although patient case presentation during ward rounds is an important component in the interaction between the medical team and the patient, few rigorous studies have investigated whether bedside or non-bedside presentation of patients results in better quality of care. We found no significant difference in patient’s satisfaction, or in patient’s understanding of disease and the management plan, and in the majority of other patient and provider-relevant secondary outcomes according to type of presentation.

To further investigate whether the negative results are due to insufficient power or lack of effect, we performed TSA, a methodology that combines an information size calculation (cumulated sample sizes of all included trials) for a meta-analysis with the threshold of statistical significance.16 TSA is a tool for quantifying the statistical reliability of data in the cumulative meta-analysis and can be viewed as an interim meta-analysis. Based on this analysis, we found that the current number of patients included is too small to find a difference by type of patient presentation. If a trial was to compare patient presentation, the number of included patients would need to be very large to avoid the risk for type II error. This conclusion, however, is based on estimates of current trials which were limited by both, trial quality and number of included patients.

Although, based on randomized trials included in our analysis, we found no significant effect of bedside presentation on low patient’s satisfaction, results from observational research reported positive associations between satisfaction and bedside case presentations.6,17,18,19,20 These discrepancies may be explained by factors like differences in patient population and uncontrolled confounding in observational research. Similarly, regarding the outcome understanding of disease and the management plan, observational and non-randomized research found some positive associations with bedside presentation, while our analysis did not find significant effects. Specifically, a study conducted on a pediatric intensive care unit using a cross-over design found parents in the bedside case presentation condition to have stronger agreement with being well informed about tests than parents in the non-bedside case presentation condition.19 Yet, there was no difference in agreement to being well informed about diagnosis or treatment plan.

Interestingly, qualitative research indicated that patients prefer bedside case presentation because physicians would spend more time with the patient8 and patients felt that the medical team was more compassionately.9 In our analysis, we were not able to look at outcomes such as emotional support and time spend with the patient, as included trials did not report such endpoints. Clearly, these outcomes should be investigated in future randomized trials.

Perceptions of the physician and nursing teams towards type of patient presentation was inconsistent across previous studies. Non-bedside patient case presentation was preferred by physicians in one trial,11 while physicians in another trial favored bedside case presentation.12 Interestingly, in another trial,10 47% of physicians and advanced practice providers indicated that bedside rounds improved communication with patients, but only 37% agreed that bedside round improved the efficiency of their workday. Time constraints were also found to be important factors in favor of non-bedside case presentation as physicians perceived bedside presentation to be more time consuming.21,22,23 Still, a study comparing the time spend on the ward rounds between bedside and non-bedside did not find significant differences.17 Again, future trials should also look at timing of ward rounds as this is an important factor in clinical routine.

We are aware of several limitation of this analysis. First, included trials displayed substantial methodological weaknesses indicating limitations on the study and outcome level (see Table 3). With two exceptions,8,10 trials had low sample sizes and the majority of outcomes were assessed dichotomously limiting response variability. The included studies thus lack power to detect effects. Moreover, measures applied were mostly not validated but developed by the study authors and, accordingly, showed great heterogeneity across studies. As a consequence, results are difficult to compare, and we were only able to include two outcomes for aggregate analysis, namely low patient’s satisfaction and low patient’s understanding of disease and the management plan. Second, we only found a small number of trials to be eligible for this review. However, results from the Begg and Egger test did not indicate high risk for publication bias.

In conclusion, we have low knowledge how to best communicate the complex medical issues and therapeutic options with the aging patient population during ward rounds. Such knowledge, however, is key to proactively engage patients in these important decisions. This systematic search and meta-analysis found no differences in patient-relevant outcomes between bedside and non-bedside case presentations with, however, an important lack of statistical power among current trials limiting strong conclusions. There is a need for larger studies to find the optimal approach to patient case presentation during ward rounds.

References

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm : A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, CC: National Academy Press; 2001.

Berwick DM. What ‘patient-centered’ should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w555–65.

Epstein RM, Street RL, Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100–3.

Langewitz W, Ackermann S, Heierle A, Hertwig R, Ghanim L, Bingisser R. Improving patient recall of information: Harnessing the power of structure. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:716–21.

Krupp W, Spanehl O, Laubach W, Seifert V. Informed consent in neurosurgery: patients’ recall of preoperative discussion. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142:233–8; discussion 8–9.

Wang-Cheng RM, Barnas GP, Sigmann P, Riendl PA, Young MJ. Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:284–7.

Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, Riley RD, Simmonds M, Stewart G, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD Statement. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;313:1657–65.

Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1150–5.

Ramirez J, Singh J, Williams AA. Patient’s satisfaction with Bedside Teaching Rounds Compared with Nonbedside Rounds. South Med J. 2016;109:112–5.

O’Leary KJ, Killarney A, Hansen LO, Jones S, Malladi M, Marks K, et al. Effect of patient-centred bedside rounds on hospitalised patients’ decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:921–8.

Seo M, Tamura K, Morioka E, Shijo H. Impact of medical round on patients’ and residents’ perceptions at a university hospital in Japan. Med Educ. 2000;34:409–11.

Chauke HL, Pattinson RC. Ward rounds -- bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006;96:398–400.

Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The Control Preferences Scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29:21–43.

Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health services research. 2005;40:1918–30.

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14:353–8.

Thorlund K, Devereaux PJ, Wetterslev J, Guyatt G, Ioannidis JP, Thabane L, et al. Can trial sequential monitoring boundaries reduce spurious inferences from meta-analyses? International journal of epidemiology. 2009;38:276–86.

Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:792–8.

Janicik RW, Fletcher KE. Teaching at the bedside: a new model. Med Teach. 2003;25:127–30.

Landry MA, Lafrenaye S, Roy MC, Cyr C. A randomized, controlled trial of bedside versus conference-room case presentation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2007;120:275–80.

Rogers HD, Carline JD, Paauw DS. Examination room presentations in general internal medicine clinic: patients’ and students’ perceptions. Acad Med. 2003;78:945–9.

Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, Dyrbye L, Fagan MJ, Ferenchick G, et al. Identifying and overcoming the barriers to bedside rounds: a multicenter qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89:326–34.

Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Impediments to bed-side teaching. Med Educ. 1998;32:159–62.

Williams KN, Ramani S, Fraser B, Orlander JD. Improving bedside teaching: findings from a focus group study of learners. Acad Med. 2008;83:257–64.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jørn Wetterslev, Chief Physician at the Copenhagen Trial Unit, for helpful discussions regarding TSA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Martina Gamp and Sabina Hunziker designed the study. Christoph Becker and Martina Gamp performed the literature search. Theresa Tondorf, Seraina Hochstrasser, and Kerstin Metzger contributed to the discussion part. Wolf Langewitz, Rainer Schäfert, Gunther Meinlschmidt, and Stefano Bassetti revised the manuscript critically. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 27 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gamp, M., Becker, C., Tondorf, T. et al. Effect of Bedside vs. Non-bedside Patient Case Presentation During Ward Rounds: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 447–457 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4714-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4714-1