ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Whether sex disparities exist in overall burden of disease among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals in the Veterans Affairs healthcare system (VA) is unknown.

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether sex differences exist in overall burden of disease after 1 year of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) among HIV-infected individuals in VA.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort study.

PARTICIPANTS

Among patients in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study Virtual Cohort (VACS-VC), all ART-naïve HIV-infected Veterans who received VA-based HIV care between 1996 and 2009.

MAIN MEASURES

Overall burden of disease was measured using the VACS Index, an index that incorporates HIV (e.g. CD4 cell count) and non-HIV biomarkers (e.g. hemoglobin) and is highly predictive of all-cause mortality. Possible scores range from 0 to 164, although scores typically range from 0 to 50 for 80 % of patients in VACS-VC. A higher score indicates greater burden of disease (each additional five points indicates approximately 20 % increased 5-year mortality risk). ART adherence was measured using pharmacy data.

KEY RESULTS

Complete data were available for 227 women and 8,073 men. At ART initiation, compared with men, women were younger and more likely to be Black, less likely to have liver dysfunction, but more likely to have lower hemoglobin levels. Median VACS Index scores changed from ART initiation to 1 year after ART initiation: women’s scores went from 41 to 28 for women (13 point improvement) and men’s from 42 to 27 for men (15 point improvement). In multivariable regression, women had 3.6 point worse scores than men after 1 year on ART (p = 0.002); this difference decreased to 3.2 points after adjusting for adherence (p = 0.004).

CONCLUSIONS

In VA, compared to men, women experienced less improvement in overall burden of disease after 1 year of HIV treatment. Further study is needed to elucidate the modifiable factors that may explain this disparity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Since the introduction of combined antiretroviral treatment (ART), there has been accumulating evidence of sex disparities in HIV-related care and outcomes in the United States, with women, in general, faring worse than men.1–8 Prior studies have found that HIV-infected women report worse health-related quality of life8 and have greater HIV-related morbidity,5 as well as HIV-related6 and all-cause mortality,6,7 compared to HIV-infected men. These health disparities have been attributed, in part, to differences in access to care,1,7 quality of care,1–4 and ART adherence.9–12

It is unknown whether similar disparities exist between HIV-infected women and men in the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system. VA is the largest single provider of HIV care in the United States, providing care to over 24,000 HIV-infected Veterans annually.13 Within VA, women and men share similar sociodemographic characteristics, such as limited economic resources. Additionally, the potential barrier of access based on health insurance is similarly reduced for both groups.

As the number of women Veterans seeking VA care continues to increase, it is expected that the number of HIV-infected women in VA care—currently 3 % of HIV-infected persons in VA care—will also rise.14,15 However, there is a lack of research examining health outcomes among this unique population of women Veterans and whether sex disparities in outcomes exist among HIV-infected persons in VA care. Therefore, among HIV-infected individuals in VA care, we sought to determine whether differences exist by sex in overall burden of disease after 1 year of ART.

METHODS

Data Source

We used data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study Virtual Cohort (VACS-VC), a clinical cohort of 32,747 HIV-infected persons in care at VA facilities nationally.16 VACS-VC consists of data from the Clinical Case Registry, the VA’s HIV registry; the Pharmacy Benefits Management database, which provides outpatient pharmacy data; and the Decision Support System, a national database of clinical data including coded diagnoses and laboratory values. We received Institutional Review Board approval for this study from VA Connecticut Healthcare System and the Yale University School of Medicine.

Study Population

Among the HIV-infected persons in the VACS-VC (821 women, 31,926 men), we included persons 1) with a date of entry to HIV care between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2009; 2) who were confirmed to be receiving HIV care at a VA healthcare facility; and 3) who were ART-naïve, defined as having received no prior ART prescriptions while in VA care and an HIV RNA level > 500 copies/mL within 6 months prior to ART initiation. Date of entry to HIV care was defined as the earliest date of any of the following: ICD-9 code for HIV diagnosis (042 or V08) (1st inpatient or 2nd outpatient), CD4 cell count, or HIV RNA level. Patients were confirmed to be receiving HIV care if there was evidence of a CD4 cell count, HIV RNA level, or ART prescription at a VA healthcare facility.

Measures

Overall burden of disease was measured using the VACS Index, a validated index predictive of morbidity and mortality which incorporates HIV and non-HIV biomarkers.17,18 The VACS Index is calculated using the patient’s age, CD4 cell count; HIV RNA level and hemoglobin levels; renal and hepatic function; and Hepatitis C virus serostatus (Table 1).17,18 Possible VACS Index scores range from 0 to 164 points with higher scores indicating greater burden of disease and higher risk of morbidity and mortality; scores range from 0 to 50 points for 80 % of patients in VACS-VC.19 A 5-point difference in VACS Index corresponds to an approximately 20 % change in 5-year mortality risk.19,20 Time intervals used to identify routine clinical tests for calculation of the VACS Index were consistent with prior VACS studies.19

ART adherence was measured using the medication possession ratio (MPR), a validated measure of medication adherence. MPR is the sum of the days’ supply of ART in a specific period divided by the total number of days during the specified period; in this case, 365 days.21,22 The MPR was dichotomized as < 80 % (poor adherence) vs. ≥ 80 % (high adherence).23

Statistical Analysis

We used chi-square and Wilcoxon-rank sum tests to compare VACS Index components and total VACS Index scores by sex at ART initiation and after 1 year on ART. We assessed the association between sex and our outcome of interest, VACS Index score after 1 year on ART, with and without adjustment for VACS Index score at ART initiation, age, and poor ART adherence using linear regression. VACS Index score at ART initiation was centered at the median (42), so that the intercept for models adjusted for score at ART initiation represents those with the median value rather than zero. Age, modeled in 5-year increments, was centered at 47, such that the intercept, in models adjusted for age, represents the 1-year score for a 47-year-old patient. We used age at ART initiation when calculating all VACS Index scores to avoid increasing scores due to the increase in age by 1 year. We included age in multivariate models, because women in our cohort were younger and we wanted to adjust for this potential confounder. Associations with VACS Index score at 1 year after ART initiation are presented as betas (β) with associated 95 % confidence intervals (CI) and p values. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Of 275 women and 9,809 men who met study criteria, complete data were available for 227 women (82.5 %) and 8,073 men (82.3 %) at both ART initiation and 1 year after. At ART initiation, women were younger (42 [IQR 37–48] vs. 47 [IQR 40–53] years, p < 0.001) and more likely to be Black (69.2 % vs. 55.1 %, p < 0.001) (Table 2). Women were less likely to have liver dysfunction (33 % vs. 48 %, p < 0.001), but more likely to have lower hemoglobin levels (12.0 vs. 13.4 [IQR 12.0–14.6] g/dL, p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences by sex with respect to CD4 cell count (237 [IQR 100–363] vs. 230 [IQR 68–341] cells/mm3, p = 0.07), HIV RNA levels, renal function, Hepatitis C infection, or VACS Index score.

Association Between Patient Sex and Overall Burden of Disease 1 Year After ART Initiation

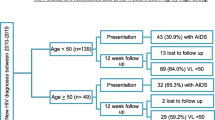

VACS Index scores, our measure of overall burden of disease, changed for both groups over 1 year of ART (Fig. 1). Baseline to 1 year scores changed from: 41 to 28 for women (13 point improvement), equivalent to a decrease of 8.8 % in 5-year mortality risk; and 42 to 27 for men (15 point improvement), a decrease of 10.2 % in 5-year mortality risk. Because the translation of a difference in VACS Index score to an expected mortality rate depends upon baseline score, one must interpret these changes in this context.

In unadjusted analysis, patient sex was not associated with VACS Index score 1 year after ART initiation (β, +1.3, 95 % CI, −1.7 to 4.3) (Table 3). However, VACS Index score at ART initiation, age, and poor ART adherence were each significantly associated with score at 1 year after ART initiation. In multivariable analysis, women’s scores were 3.6 points higher (i.e. greater overall burden of disease) than men (p = 0.002). Thus, adjusted differences in VACS Index score were even greater than in our unadjusted analyses. After further, adjustment for ART adherence, women’s scores remained 3.2 points higher than men (p = 0.004).

DISCUSSION

HIV-infected women in the VA Healthcare system experience less improvement in overall burden of disease after 1 year of ART compared to HIV-infected men, a difference only modestly explained by ART adherence. This study, which utilized a large clinical cohort of HIV-infected Veterans in VA-based HIV care, represents the first comprehensive analysis of health outcomes for HIV-infected women Veterans in VA care.

Our findings contribute to characterizing and understanding health outcomes for HIV-infected women in VA care. By using the VACS Index, a measure of overall burden of disease that includes both HIV and non-HIV biomarkers, we were able to go beyond what traditional measures (e.g. CD4 cell count) tell us about morbidity to capture a more global assessment of health among HIV-infected women Veterans, including their response to treatment. This is particularly important, given the increased contribution of non-AIDS defining disease to morbidity and mortality in the ART era and the complex interplay of HIV infection, ART and comorbid disease in an aging HIV population. In validation studies of the VACS Index, we also looked at whether hemoglobin level behaved differently between women and men in its contribution to VACS Index score and its association with mortality, and found no evidence that it did.19 Further, VACS Index predicted mortality rates matched observed rates as well for men as for women.20 Results from prior studies of HIV-related sex disparities using traditional HIV biomarkers have been mixed with respect to whether or not sex differences exist in response to ART;24–27 however, larger studies have found no sex differences in ART response.28–31 How findings from these studies would have differed if overall burden of disease were assessed is unknown. Additionally, our study findings suggest that differences in ART adherence only minimally contribute to this disparity in ART response.

Our study has several limitations. First, to calculate the VACS Index requires data on eight routine clinical tests. However, we had complete data for over 80 % of individuals in our study sample at the two clinical time points. Second, since the study’s focus was on the VA population, our results may not be generalizable to HIV-infected persons who receive care outside the VA healthcare system, as the VA HIV population is older than the general HIV population. It is also affected by a substantial burden of chronic comorbid disease,32,33 which has been increasingly ascribed to HIV-associated chronic inflammation as well as ART-associated toxicity.18,34–36 Additionally, HIV-infected women Veterans may differ from HIV-infected women who are not Veterans with respect to certain sociodemographic characteristics and potential barriers to care, such as a history of military sexual trauma.37 Third, by using data in the medical record, we are limited in our ability to qualitatively explore the experiences of HIV-infected women Veterans in VA care and the various barriers they may face that affect their interactions with VA healthcare system. These experiences could be further assessed in the future using the VACS prospective cohort, in which patients complete annual questionnaires.33

We believe our findings have important implications for the care of HIV-infected women Veterans and for future research aimed at improving their health outcomes. Further study is needed to elucidate modifiable factors that may explain the observed sex disparity in ART response, such as ART-associated toxicity. Prior research suggests that women experience more and different types of ART-related adverse events and toxicity compared with men;38–40 this difference may affect health outcomes not only due to increased discontinuation of ART, but to direct toxic effects of ART. Also, the use of non-HIV biomarkers in addition to traditional HIV biomarkers in assessing overall burden of disease among HIV-infected persons in care provides a more comprehensive evaluation of health; potential differences between groups, such as HIV-infected women and men in VA care, may not be apparent when only traditional HIV biomarkers are considered. This suggests that broader use of measures, such as the VACS Index, in clinical care and research would be useful. Future studies of this disparity in ART response will need to explore the role of psychosocial and structural factors that differentially impact women Veterans, such as military sexual trauma, as well as whether sex differences in ART response persist over longer periods of follow-up.

In this study of HIV-infected Veterans in VA care, women had less improvement in overall burden of disease after 1 year on ART compared with men. As HIV-infected women Veterans represent a vulnerable group within a population already at high risk for poor health outcomes, it is particularly important that the root causes of this observed disparity be identified and appropriately addressed.

REFERENCES

Mocroft A, Gill MJ, Davidson W, Phillips AN. Are there gender differences in starting protease inhibitors, HAART, and disease progression despite equal access to care? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:475–82.

McNaghten AD, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, Jones JL. Differences in prescription of antiretroviral therapy in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:499–505.

Gebo KA, Fleishman JA, Conviser R, et al. Racial and gender disparities in receipt of highly active antiretroviral therapy persist in a multistate sample of HIV patients in 2001. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:96–103.

Hirschhorn LR, McInnes K, Landon BE, et al. Gender differences in quality of HIV care in Ryan White CARE Act-funded clinics. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16:104–12.

Meditz AL, MaWhinney S, Allshouse A, et al. Sex, race, and geographic region influence clinical outcomes following primary HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:442–51.

Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:397–406.

Lemly DC, Shepherd BE, Hulgan T, et al. Race and sex differences in antiretroviral therapy use and mortality among HIV-infected persons in care. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:991–8.

Mrus JM, Williams PL, Tsevat J, Cohn SE, Wu AW. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients with HIV/AIDS. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:479–91.

Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, et al. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:377–81.

Turner BJ, Laine C, Cosler L, Hauck WW. Relationship of gender, depression, and health care delivery with antiretroviral adherence in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:248–57.

Berg KM, Demas PA, Howard AA, Schoenbaum EE, Gourevitch MN, Arnsten JH. Gender differences in factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1111–7.

Delgado J, Heath KV, Yip B, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy: physician experience and enhanced adherence to prescription refill. Antivir Ther. 2003;8:471–8.

Department of Veterans Affairs. National HIV/AIDS Strategy Operation Plan. 2011. Available at: http://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/policies/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-operational-plan-va.pdf. Accessed on January 7, 2012.

Department of Veterans Affairs. The State of Care for Veterans with HIV/AIDS. 2009. Available at: http://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/state-of-care/index.asp. Accessed on January 7, 2012.

Duggal M, Goulet JL, Womack J, et al. Comparison of outpatient health care utilization among returning women and men veterans from Afghanistan and Iraq. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:175.

Fultz SL, Skanderson M, Mole LA, et al. Development and verification of a "virtual" cohort using the National VA Health Information System. Med Care. 2006;44:S25–30.

Justice AC, Freiberg MS, Tracy R, et al. Does an index composed of clinical data reflect effects of inflammation, coagulation, and monocyte activation on mortality among those aging with HIV? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:984–94.

Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, et al. Towards a combined prognostic index for survival in HIV infection: the role of 'non-HIV' biomarkers. HIV Med. 2010;11:143–51.

Tate JP, Justice AC, Hughes MD, et al. The VACS Index: An internationally generalizable risk index for mortality after one year of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2012. Epub ahead of print. PMID 23095314.

Justice A, Modur S, Tate J, et al. Predictive accuracy of the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) Index for Mortality with HIV Infection: A North American Cross Cohort Analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 23187941.

Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:565–74. discussion 75–7.

Steiner JF, Koepsell TD, Fihn SD, Inui TS. A general method of compliance assessment using centralized pharmacy records. Description and validation. Med Care. 1988;26:814–23.

Hirsch JD, Gonzales M, Rosenquist A, Miller TA, Gilmer TP, Best BM. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, medication use, and health care costs during 3 years of a community pharmacy medication therapy management program for Medi-Cal beneficiaries with HIV/AIDS. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17:213–23.

Moore AL, Sabin CA, Johnson MA, Phillips AN. Gender and clinical outcomes after starting highly active antiretroviral treatment: a cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:197–202.

Giordano TP, White AC Jr, Sajja P, et al. Factors associated with the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients newly entering care in an urban clinic. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:399–405.

Finkel DG, John G, Holland B, Slim J, Smith SM. Women have a greater immunological response to effective virological HIV-1 therapy. AIDS. 2003;17:2009–11.

Moore AL, Mocroft A, Madge S, et al. Gender differences in virologic response to treatment in an HIV-positive population: a cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:159–63.

Sterling TR, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. HIV-1 RNA, CD4 T-lymphocytes, and clinical response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:2251–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment -- United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Repo 2011;60:1618-123.

Moore AL, Kirk O, Johnson AM, et al. Virologic, immunologic, and clinical response to highly active antiretroviral therapy: the gender issue revisited. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:452–61.

Egger M, May M, Chene G, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–29.

Justice AC, Erdos J, Brandt C, Conigliaro J, Tierney W, Bryant K. The Veterans Affairs Healthcare System: A unique laboratory for observational and interventional research. Med Care. 2006;44:S7–12.

Justice AC, Dombrowski E, Conigliaro J, et al. Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS): overview and description. Med Care. 2006;44:S13–24.

El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–96.

Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:542–53.

Deeks SG, Phillips AN. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 2009;338:a3172.

Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Riopelle D, Yano EM. Access to care for women veterans: delayed healthcare and unmet need. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(Suppl 2):655–61.

Tedaldi EM, Absalon J, Thomas AJ, Shlay JC, van den Berg-Wolf M. Ethnicity, race, and gender. Differences in serious adverse events among participants in an antiretroviral initiation trial: results of CPCRA 058 (FIRST Study). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:441–8.

Clark R. Sex differences in antiretroviral therapy-associated intolerance and adverse events. Drug Saf. 2005;28:1075–83.

Ofotokun I, Pomeroy C. Sex differences in adverse reactions to antiretroviral drugs. Top HIV Med. 2003;11:55–9.

Acknowledgements

Funders

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (U10-AA13566), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01-HL095136; R01-HL090342; RCI-HL100347), and National Institute on Aging (R01-AG029154; K23 AG024896). This work was also funded in part by the Society of General Internal Medicine’s Lawrence S. Linn award to O.J.B. O.J.B. was supported by the Yale Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program and the Department of Veterans Affairs. J. P. T. was supported by the Training Program in Environmental Epidemiology (T32 ES07069).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Blackstock, O.J., Tate, J.P., Akgün, K.M. et al. Sex Disparities in Overall Burden of Disease Among HIV-Infected Individuals in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. J GEN INTERN MED 28 (Suppl 2), 577–582 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2346-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2346-z