Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Thai Quality of Life in Children (ThQLC) and compare it with the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL™ 4.0) in a sample of children receiving long-term HIV care in Thailand.

Methods

The ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 were administered to 292 children with HIV infection aged 8–16 years. Clinical parameters such as the current viral load, CD4 percent, and clinical staging were obtained by medical record review.

Results

Three out of five ThQLC scales and three out of four PedsQL™ 4.0 scales had acceptable internal consistency reliability (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha >0.70). Cronbach’s alpha values of each scale ranged from 0.52 to 0.75 and 0.57 to 0.75 for the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0, respectively. Corresponding scales (physical functioning, emotional well-being, social functioning, and school functioning) of the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 correlated substantially with one another (r = 0.47, 0.67, 0.59 and 0.56, respectively). Both ThQLC and PedsQL™ 4.0 overall scores significantly correlated with the child’s self-rated severity of the illness (r = −0.23 for the ThQLC and −0.28 for the PedsQL™ 4.0) and the caregiver’s rated overall quality of life (r = 0.07 for the ThQLC and 0.13 for the PedsQL™ 4.0). The overall score of the ThQLC correlated with clinical and immunologic categories of the United State-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US-CDC) classification system (r = −0.12), while the overall score of the PedsQL™ 4.0 significantly correlated with the number of disability days (r = −0.12) and CD4 percent (r = −0.15). However, the overall score from both instruments were not significantly different by clinical stages of HIV disease. A multitrait-multimethod analysis results demonstrated that the average convergent validity and off-diagonal correlations were 0.58 and 0.45, respectively. Discriminant validity was partially supported with 62% of validity diagonal correlations exceeding correlations between different domains (discriminant validity successes). The Hays-Hayashi MTMM quality index was 0.61. Multivariate regression analysis revealed that the ThQLC physical functioning scale provided unique information in predicting child self-rated severity of the illness and overall quality of life beyond that explained by the PedsQL™ 4.0 in Thai children with HIV infection.

Conclusions

We found evidence in support of the reliability and validity of the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 for measuring the health-related quality of life of Thai children with HIV infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that the number of children with HIV infection under 15 years of age in Thailand in 2008 was 14,000 [1]. With the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), children with perinatally acquired HIV infection are now surviving to adolescence. Living with a chronic health condition, children with HIV infection are at risk for low self-esteem, as well as emotional, behavioral, and social functioning problems [2–5]. In addition to monitoring clinical indicators such as viral load and CD4+ count, it is also important to assess the impact of the illness on functioning and well-being, or health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

There are two types of HRQoL measurements: generic HRQoL measurements and disease-specific measurements. Generic HRQoL tools have the advantage of being able to compare the HRQoL between patient populations, while disease-specific scales can measure HRQoL that is specifically impacted by a given disease [6]. In our project on the development of a culturally appropriate HRQoL measure for children with HIV infection in Thailand, we developed a new HIV-specific scale and, in combination of a generic HRQoL scale, evaluated their psychometric performance in Thai children with HIV infection. In our search for generic HRQoL instrument, the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ version 4.0 (PedsQL™ 4.0) Generic Core Scales and the Thai Quality of Life in Children (ThQLC) seemed most suitable.

Support for the reliability and validity of the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales has been provided for pediatric patients with chronic health conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes, and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, as well as healthy children [7]. It is a brief instrument, comprised of child self-reports and parent proxy-report formats, and can be administered to children aged 5–18 years. The PedsQL™ 4.0 has been translated into Thai and used in some Thai pediatric population [8]. However, there have been no reports of the use of this instrument among children with HIV infection.

The Thai Quality of Life in Children (ThQCL) instrument is a newly developed generic HRQoL measure designed for children aged 5–16 years [9]. The internal consistency reliability for the ThQCL total score was 0.85 for child self-report and 0.89 for parent report. Support for the construct validity of the ThQCL was noted by significantly higher scores for healthy children compared to children with chronic illnesses, both by self-reports and by parents’ reports (P < 0.05) [9].

While validity of the HIV-specific module was assessed in another study, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the reliability and validity of the Thai Quality of Life in Children (ThQLC) and compare it with the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL™ 4.0) in children with HIV infection receiving long-term treatment in Thailand.

Methods

Study design and population

The target population for this study was children with HIV infection receiving treatment in the Infectious Clinic at QSNICH and Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand, during the period of April 2007 to March 2008. Children with HIV infection were recruited if they (1) were aged between 8 and 16 years; and (2) had never been diagnosed with a neurological, developmental, or psychiatric disorder. Informed consent and assent were obtained from all children and their legal guardians prior to the enrollment in the study. Out of 316 children approached, 292 (92%) were ultimately enrolled in the study.

The children were asked to complete the HRQoL instruments (the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales) one time on the occasion of a routinely scheduled clinic visit. The instruments were self-administered for children aged 12 years or older and were completed via individual interview by a research team member for those who were younger than 12 years old. The children were asked to rate the perceived severity of their HIV disease using a 10-point visual analog scale. The children’s primary caregivers were also asked to complete a questionnaire assessing demographic data, number of disability days in the past month, and rate their child’s overall quality of life using a 10-point visual analog scale. The children’ medical records were reviewed to obtain clinical parameters including current viral load, CD4 percent, and clinical staging based on the United State-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US-CDC) classification system [10].

The Ethical Committee’s approvals were obtained from Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health (QSNICH), Siriraj Hospital, and the University of California, Los Angeles (IRB approval numbers of 50-037, Si 252/2007, and G05-10-110-02 for the three centers, respectively).

Measures

The PedsQL™ 4.0 generic core scales

The PedsQL ™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales consist of 23 items representing four domains: Physical Functioning (8 items); Emotional Functioning (5 items); Social Functioning (5 items); and School Functioning (5 items) and are composed of parallel child self-report and parent proxy-report formats. Child self-report includes ages 5–7, 8–12, and 13–18 years. The items for each of the forms are essentially identical, differing in developmentally appropriate language. Each item is scored from 0 (never a problem) to 4 (almost always a problem, or most of the time), giving a possible range of 0–92 for the total score comprised of all 23 questions. Scores on all of the scales were created by averaging items within scales and transforming them linearly to a possible score of 0–100. Higher scores indicate better HRQoL [7].

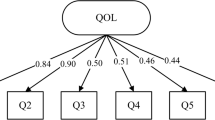

The ThQLC

The ThQLC contains 24 questions representing 5 domains: Physical Functioning (5 items); Emotional Functioning (5 items); Social Functioning (5 items); School Functioning (5 items); and Life Perspective (4 items). It has parallel child self-report and parent proxy-report formats. Each question is scored in the five-point categorical response scale from 0 to 4, giving a possible score of 0–96 for the total score comprised of all 24 questions. Overall scores were created by averaging items within scales and transforming them linearly to a possible score of 0–100, so that higher scores represent better HRQoL [9].

In this study, only the child report versions of the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales (scales for 8–12 and 13–18 years) were used. Both child report instruments require 5–15 min to complete.

Data analysis

The mean score, standard deviation (SD), ranges, and percentage of respondents scoring the minimum (floor) and maximum (ceiling) possible scores of the two instruments were calculated. Internal consistency reliability of each scale was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha, which by convention should be at least 0.70 to be acceptable for group comparisons [11]. In addition, the associations of the physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, and school functioning scales between the instruments were estimated using product-moment correlations. Agreement and scatter bias were examined by graphically comparing those scale scores of the ThQLC against those of the PedsQL™ 4.0 using the method of Bland and Altman [12]. We also examined the correlations of the scale scores of both instruments with child self-rated severity of the disease, caregiver-rated overall quality of life, number of disability days, CD4 percent, log viral load, and US-CDC clinical and immunologic categories.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Two hundred and ninety-two children with HIV infection (132 girls, 160 boys: mean age = 10.9; SD = 2.27) who received treatment at the two hospitals were enrolled in this study. More than half the children were either asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic clinical stage based on the US-CDC Classification System. Thirty-six percent of children had been disclosed of their HIV diagnosis prior to the time of study. Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Internal consistency reliability

Internal consistency reliability coefficients for three out of five scales of the ThQLC and three out of four scales of the PedsQL™ 4.0 met the 0.70 minimum reliability standard, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.52 to 0.75 and from 0.57 to 0.75 for the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0, respectively (Table 2). The reliability of the PedsQL™ 4.0 physical functioning scale was significantly higher than the reliability of the ThQLC physical functioning scale (P < 0.001) [13].

Validity

Emotional, social, and school functioning scales of both the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 had noteworthy intercorrelations (r’s ranged from 0.56 to 0.67). The rest of the correlations between the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 scales ranged from 0.32 to 0.48 [14] (Table 3).

We examined the convergent and discriminant validity of the four overlapping HRQoL domains assessed by the two methods (instruments) using multitrait-multimethod (MTMM) analysis [15]. Convergent validity was calculated using the average Pearson product-moment correlation among the eight validity diagonals in the MTMM matrix. The average convergent validity correlation was 0.58, indicating reasonable convergence across methods. The average off-diagonal correlation was 0.45 (Table 4). Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing validity diagonals with appropriate off-diagonal values. The t-tests of the difference between dependent correlations indicated that 30 out of 48 t-tests were statistically significant in the hypothesized direction, supporting the discriminant validity of measures (Table 5) [16]. However, the discriminant validity for physical health was not as satisfactory (only 3 out of 12 tests were significant). The Hays-Hayashi MTMM quality index was 0.61. Finally, Bland and Altman plots demonstrated good agreement as shown by the relatively small number of points falling outside the 95% limits [12] (Fig. 1).

Bland and Altman plot of physical (a), emotional (b), social (c), and school (d) functioning subscale for the PedsQL™ 4.0 and the ThQLC. The solid line represents the mean difference and the dashed lines 95% limits of agreement: 6.18 ± 31.81, 3.69 ± 28.6, 6.18 ± 29.2, and 1.88 ± 29.5 for physical, emotional, social, and school functioning scale, respectively

All four scales scores and overall scores of both instruments correlated significantly with the child’s self-rated severity of the illness. All four scales of the ThQLC correlated significantly with caregiver-rating of child’s overall quality of life, while the social functioning scale and the overall scores correlated with disease severity as categorized by the clinical and immunologic status (Table 6). The PedsQL™ 4.0 overall score significantly correlated with the number of disability days and CD4 percent (Table 7). Multivariate regression analysis demonstrated that the physical functioning scale of ThQLC captured unique information concerning the child self-rated severity of the illness and overall quality of life beyond that of the PedsQL™ 4.0 (Table 8). The model R-squared was 13 and 26% for child self-rated severity of the illness and overall quality of life, respectively.

The mean overall scores of both instruments were compared among US-CDC clinical staging of N, A, B, and C, using One-way ANOVA test. The results were not statistically significant.

Discussion

This study evaluated the reliability and validity of the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 in a sample of 292 children with HIV infection receiving treatment in Thailand. Internal consistency reliability met the threshold for group comparisons of 0.70 for three out of five scales of the ThQLC and three out of four scales of the PedsQL™ 4.0. The significant reliability for the PedsQL™ 4.0 physical functioning scale compared to the ThQLC scale in part reflects the fact that the physical functioning domain of PedsQL™ 4.0 contains 8 questions, while that of the ThQLC contains 5 questions. It is possible that the higher number of questions may contribute to the higher level of this statistics, particularly in this kind of patient population. Both instruments exhibited low internal consistency reliability on the school functioning scale. This could be due to the fact that the school functioning scale of both instruments contains questions in many aspects of school functioning, which include ability to attend school and functioning in the classroom, while our sample did not consistently have impairments in these aspects.

The results of MTMM analysis indicate adequate convergent validity between the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 and suggest that the two instruments provide relatively similar information. Furthermore, the extent of conformity illustrated by the Bland and Altman plots indicates that there is no consistent systematic bias. Although the reliability of the PedsQL™ 4.0 scales overall was higher than that of the ThQLC scales, there are some more potential advantages of the ThQLC. First, the ThQLC contains an extra psychological dimension, life perspective, which might be valuable in the context of childhood HIV disease. Second, the physical functioning scale of ThQLC captured unique information concerning the child self-rated severity of the illness and overall quality of life beyond that of the PedsQL™ 4.0. Moreover, the ThQLC was developed in the Thai language and its questions were framed in a way that is considered to be pertinent to the Thai context. For example, during the piloting of the questionnaires before the survey, we identified that the Thai children were not familiar with the concept of the ‘one block’ walking distance that is used in one of questions of the PedsQL™ 4.0. In contrast, all the questions in ThQLC were considered to be culturally appropriate by these children.

As there is no universally accepted gold standard for subjective measurement that can be used to validate an HRQoL instrument, we used several assessments for validation. The results of this study found evidence in support of convergent and discriminant validity by the MMTM analysis. In addition, all the scales of both instruments correlate significantly with the child’s self-rated severity of the illness and caregiver’s rated overall quality of life. Using self-rated disease severity for validation was consistent with other studies of HRQoL among HIV-infected population [17–19]. Nevertheless, HRQoL scores did not consistently correlate with other important clinical parameters. Another counterintuitive finding was the absence of any statistically significant correlation between the overall score from both instruments and the CDC clinical stage. This might be due to the fact that our sample was drawn from outpatient settings where almost all subjects were clinically well regardless of their initially clinical staging. For instance, most of the clinical conditions of these children, despite being classified as class C, had been brought under control by potent antiretroviral and antimicrobial agents. It is also possible that this particular clinical parameter is not a sensitive indicator of the overall sense of well-being of these patients, since it does not capture any subjective aspect of how the patient perceives his/her illness. This can be seen by the fact that the HRQoL scores from both instruments strongly correlated with the self-rated severity of the illness and caregivers’ rated overall quality of life of their child.

There are certain study limitations. First, the study was cross-sectional. Therefore, we were unable to test whether these instruments differ in their ability to detect changes of the children’s HRQoL overtime. Second, the response to the questionnaire was obtained differently for older children (self-administered) and children younger than 12 years of age or were unable to read the questionnaires (by interview). Using two different approaches might have yielded answers with different degrees of candidness.

Furthermore, this study was conducted in only children with HIV infection being treated with highly active antiretroviral agents in multidisciplinary team treatment settings. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other populations, and further studies in other group of children with HIV infection are therefore warranted. Lastly, as both the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 measures are not disease-targeted, they might not be sufficiently sensitive to specific aspects of HRQoL related to HIV infection and should be used when possible in conjunction with an HIV-targeted QoL measure.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide support for the reliability and validity of the ThQLC and the PedsQL™ 4.0 among the children with HIV infection receiving treatment. The psychometric property of the newly developed ThQLC is comparable to that of the PedsQL™ 4.0, except for having lower internal consistency reliability in the physical functioning domain. Nevertheless, the ThQLC has an advantage of having an additional life perspective domain. We do not have enough evidence to conclude that either of the two measures is a sufficient tool for assessing the effectiveness of HIV treatment on quality of life. An HIV-targeted scale supplement may be essential for improving their responsiveness or sensitivity to detect a small, yet clinically significant difference of HRQoL across subgroups of population with different levels of disease severity.

Abbreviations

- HAART:

-

Highly active antiretroviral treatment

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- ThQLC:

-

Thai Quality of Life in Children

- PedsQL™ 4.0:

-

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ version 4.0

- US-CDC:

-

United State-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2008 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Available from URL: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/. Accessed 12 Dec 2009.

Remien, R. H., & Mellins, C. A. (2007). Long-term psychosocial challenges for people living with HIV: Let’s not forget the individual in our global response to the pandemic. AIDS, 21(Suppl 5), S55–S63.

Justice, A. C., Holmes, W., Gifford, A. L., Rabeneck, L., Zackin, R., Sinclair, G., et al. (2001). Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(Suppl 1), S77–S90.

Li, X., Naar-King, S., Barnett, D., Stanton, B., Fang, X., & Thurston, C. (2008). A developmental psychopathology framework of the psychosocial needs of children orphaned by HIV. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 19(2), 147–157.

WHOQOL (World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Instrument) HIV Group. (2003). Initial steps to developing the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQOL) module for international assessment in HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care, 15(3), 347–357.

Patrick, D. L., & Deyo, R. A. (1989). Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Medical Care, 27(3 Suppl), S217–S232.

Varni, J. W., Seid, M., & Rode, C. A. (1999). The PedsQL: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Medical Care, 37(2), 126–139.

Pongwilairat, K., Louthrenoo, O., Charnsil, C., & Witoonchart, C. (2005). Quality of life of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, 88(8), 1062–1066.

Daosukho, S. (2006). The pilot study development of Thai children quality of life inventory. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the diploma of the Thai board of pediatrics.

CDC. (1994). Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 43, 1–19.

Cronbach, L. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334.

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1986). Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet, 1(8476), 307–310.

Feldt, L. S., Woodruff, D. J., & Salih, F. A. (1987). Statistical inference for coefficient alpha. Applied Psychological Measurement, 11, 93–103.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hayashi, T., & Hays, R. D. (1987). A microcomputer program for analyzing multitrait-multimethod matrices. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 19(3), 345–348.

Steiger, J. H. (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87, 245.

Fang, C. T., Hsiung, P. C., Yu, C. F., Chen, M. Y., & Wang, J. D. (2002). Validation of the World Health Organization quality of life instrument in patients with HIV infection. Quality of Life Research, 11(8), 753–762.

Peterman, A. H., Cella, D., Mo, F., & McCain, N. (1997). Psychometric validation of the revised Functional Assessment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection (FAHI) quality of life instrument. Quality of Life Research, 6(6), 572–584.

Holmes, W. C., & Shea, J. A. (1997). Performance of a new, HIV/AIDS-targeted quality of life (HAT-QoL) instrument in asymptomatic seropositive individuals. Quality of Life Research, 6(6), 561–571.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health, and the Infectious Disease Division, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, for their support of this project. Most importantly, the authors express their gratitude to the children and families who participated in this project. This research was funded by the NIH Fogarty/UCLA AIDS International Research and Training Program (D43 TW000013). Dr. Hays was supported in part by the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement in Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME), NIH/NIA Grant Award Number P30AG021684, the UCLA/Drew Project EXPORT, NCMHD, 2P20MD000182, and the UCLA Older Americans Independence Center, NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG028748.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Punpanich, W., Boon-yasidhi, V., Chokephaibulkit, K. et al. Health-related Quality of Life of Thai children with HIV infection: a comparison of the Thai Quality of Life in Children (ThQLC) with the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ version 4.0 (PedsQL™ 4.0) Generic Core Scales. Qual Life Res 19, 1509–1516 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9708-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9708-3