Abstract

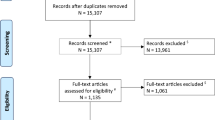

There is no current consensus regarding routine screening of high-risk asymptomatic trauma patients for venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE refers to the presence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism (PE). Practices among surgeons related to screening for VTE in asymptomatic patients may vary significantly. Supporters of routine screening see benefit in performing a relatively inexpensive and noninvasive test (Duplex ultrasonography), in order to diagnose and treat asymptomatic DVT before it progresses to symptomatic or fatal PE. Others suggest that increased medical testing and treatment of asymptomatic VTE incurs not only the risk associated with anticoagulation treatment, but also unnecessary costs. Surveillance bias (“the more you look, the more you find”) in VTE outcome reporting is perhaps an unintended consequence of varying screening practices. Studies have clearly shown that increasing screening is associated with increasing rates of VTE diagnosis, primarily in trauma patients. This poses significant concern because lower incidence of VTE is considered a marker for higher quality health care. National bodies, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, impose financial penalties when some hospitalized patients develop VTE. Furthermore, healthcare consumers may use VTE outcomes data to make decisions about where to seek higher quality care. Since the incidence of VTE is related to screening practices, providers who screen more aggressively by performing more Duplex ultrasounds on asymptomatic patients may identify more cases of VTE and will appear, paradoxically, to provide lower quality care than providers who do not screen or order fewer screening tests. For this reason, some experts argue that the standard of patient safety and quality care should not only focus on the incidence of VTE alone (outcome measure) but should also consider how frequently patients are prescribed and administered VTE prophylaxis according to best-practice guidelines (process measure). A pure process measure approach or combined process and outcome measure may be more effective to identify higher quality care and to ultimately mitigate preventable harm related to VTE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

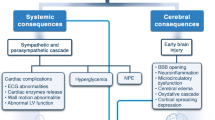

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), or the presence of both, are referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE). Over 100,000 people will die from VTE in the USA each year, and national expenditures for this disease may be as high as US$10 billion [1, 2•]. DVT is almost exclusively diagnosed with Duplex ultrasonography and PE is most commonly diagnosed with multiple-detector contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) angiography. Anticoagulation remains the mainstay of treatment for VTE to prevent recurrence and associated sequelae. Prophylaxis guidelines, diagnosis approaches, and treatment algorithms for VTE are widely published elsewhere [3••, 4••, 5, 6]. This report will use the VTE example to demonstrate how variations in screening practices may lead to surveillance bias in outcome reporting. For this reason, outcome measures alone may not be the best benchmark for higher quality care. The VTE example will also provide opportunity to review the argument for linking outcome measures and process measures as a more acceptable definition of potentially preventable harm and ultimately a more impactful metric for patient safety and quality health care.

A Case Example for Patient Safety and Healthcare Quality

VTE has garnered much attention as a public health and patient safety problem. The US Surgeon General recognized VTE as “a major public health problem” and issued “A Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism” in 2008 [1]. US Congress has designated March as DVT Awareness Month to help educate the public about the symptoms of this common disease [7]. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has called VTE prophylaxis “the number one patient safety practice” to prevent in-hospital death [8, 9, 10••]. Most recently, AHRQ has placed “Strategies to increase appropriate prophylaxis for VTE” on the list of top 10 “Strongly Encouraged Patient Safety Practices” [11•, 12••]. Collectively, this national attention has allowed VTE prevention to emerge as an important case example in patient safety and healthcare quality improvement. More specifically, the VTE example highlights how variation in VTE screening practice alone clearly accounts for differences in VTE incidence among different hospitals. The incidence of VTE is more likely a function of surveillance bias than an indicator of the true quality of health care. Other measures, such as adherence to risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis guidelines, alone or in combination with VTE incidence, may provide a more accurate measure of healthcare quality.

Screening in Asymptomatic Patients

Although evidence-based guidelines for VTE prophylaxis in injured patients are widely available and accepted, there is no current consensus regarding routine screening of high-risk asymptomatic patients for VTE [3••, 4••, 5, 6]. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) does not recommend routine screening for DVT in critically ill patients [3••, 4••]. The guidelines specifically state, “For major trauma patients, we suggest that periodic surveillance with VCU [venous compression ultrasound] should not be performed (Grade 2C)” [4••]. The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) recognizes that some patients at high risk may benefit from routine screening for DVT [5]. Practices among surgeons related to screening for VTE in asymptomatic patients may vary significantly, and the practice is often debated [13••]. However, the clinical importance of asymptomatic DVT detected by routine screening remains unclear. Some older studies have found routine VTE screening of high-risk asymptomatic trauma patients clinically beneficial [14–18]. Recently, another group has shown that routine surveillance and early management of DVT may decrease rates of PE in trauma patients [19••]. Given the high incidence of asymptomatic VTE in the trauma population, even with appropriate prophylaxis, some argue that screening in these patients is warranted to diagnose and treat asymptomatic DVT before it progresses to symptomatic or fatal PE. Screening ultrasound has been shown to be a cost-effective method to prevent PE in certain high-risk trauma patients [20]. Others suggest that in the presence of appropriate VTE prophylaxis, routine surveillance is not effective at preventing clinically relevant VTE and therefore the increased cost of medical testing is not warranted [21–24]. Furthermore, treatment of asymptomatic DVT (which may never have come to clinical attention otherwise) incurs the risks associated with anticoagulation treatment.

While much of the debate in the trauma literature has surrounded practices related to Duplex ultrasound screening for DVT, recommendations related to screening for PE also exist. The Choosing Wisely campaign from the American Board of Internal Medicine aims to decrease unnecessary healthcare expenditures and improve patient care [25]. The ACCP, in conjunction with the American Thoracic Society, has encouraged providers to “choose wisely” when ordering CT angiography to screen for PE. They caution: “Do not perform chest CT angiography to evaluate for possible pulmonary embolism in patients with low clinical probability and negative results of a highly sensitive D-dimer assay” [26••]. D-dimer assay is commonly used in emergency department patients and outpatients to rule out VTE due to its high sensitivity. A negative D-dimer test can help rule out the diagnosis, but a positive test is certainly not confirmatory for VTE, especially in hospitalized surgical patients with other reasons for elevated D-dimer levels such as trauma, malignancy, infection, and the postoperative state.

There is little or no argument for routine screening for PE using CT angiography given the associated risks (including radiation as well as anaphylaxis and kidney injury from contrast dye) and costs. However, many symptoms of PE are nonspecific (tachycardia, hypoxia, etc.) and variations in frequency of diagnostic CT angiography may exist, which can lead to a similar surveillance bias as seen in Duplex ultrasonography for DVT screening. Furthermore, current multi-detector CT technology is more advanced than earlier CT models, and this imaging modality allows for increased visualization and increased diagnosis of isolated sub-segmental PEs [27•]. Little is known about the clinical significance of these types of PE events, and the prognosis is uncertain. A substantial proportion of patients with isolated sub-segmental PE (>50 %) are treated with anticoagulation, and life-threatening bleeding is not a rare complication of treatment [27•]. A recent Cochrane review examined this issue and concluded that the best treatment approach (anticoagulation versus no treatment) for isolated sub-segmental PE remains unclear [28•].

Surveillance Bias

Surveillance bias (“the more you look, the more you find” [29]) is a common concern when screening asymptomatic patients for VTE and reporting outcomes. A nonrandom type of information bias, surveillance bias (also known as detection bias or ascertainment bias) occurs when patients are followed up more closely or have more screening or diagnostic tests performed than others [30]. This often leads to an outcome diagnosed more frequently in the group with closer follow-up or more frequent tests. Validation for outcome measures has focused on strict definitions for “numerators” to clearly identify cases and for “denominators” to identify those patients at risk [31]. Less attention has focused on standard surveillance practices to identify events within the population at risk. As such, surveillance bias remains a source of error in currently reported outcome measures.

Studies, primarily in trauma patients, have clearly shown that increasing screening is associated with increasing rates of VTE [29, 32••, 33, 34]. One trauma center showed that implementation of a routine DVT screening guideline was associated with a fourfold increase in Duplex ultrasonography and a tenfold increase in rates of DVT [33]. An analysis using the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) demonstrated that hospitals in the highest quartile for use of vascular ultrasonography had a sevenfold higher rate of DVT [29]. Even when controlling for patient risk factors, patients treated at hospitals that perform more Duplex ultrasounds are more likely to have a DVT reported [34]. This phenomenon has been well documented in trauma populations, but a recent sample of nearly 1 million Medicare patients undergoing a wide range of surgical procedures has also shown higher hospital rates of VTE at hospitals with higher rates of VTE imaging [35••].

Surveillance bias is not exclusive to VTE and has long been recognized as a source of bias in analytic research [30]. Other publicly reported outcomes including rates of central line-associated bloodstream infections have also been shown to be subject to surveillance bias [36]. Imaging surveillance for tumor recurrence in oncology patients represents another example where closer follow-up or more frequent tests may result in more diagnoses [37].

Surveillance bias may lead to a number of consequences including potential harm to patients. If clinicians are unable to accurately measure quality improvement in their institution, interventions to improve patient safety may be misdirected. Since national and regional bodies recognize low incidence of VTE as a marker of quality, and in some instances impose financial penalties when a patient develops VTE, there may be an incentive for clinicians to avoid screening and diagnostic imaging to diagnose VTE. If you only see what you look for, then you will not see what you do not look for: “No screening, no DVT, no punishment,” as summarized in a comment by Alam and Velmahos [29]. In the absence of specific performance measures mandating VTE screening across hospitals, VTE incidence remains a biased measurement since hospitals that less commonly screen patients for VTE are going to identify fewer VTE events regardless of associated healthcare quality. Hospital performance becomes a function of how closely or thoroughly providers look for VTE as opposed to the true quality of care provided to patients [32••].

Public Reporting of Outcome Measures

Public reporting of outcomes is increasingly common in healthcare settings. Clinicians and policy makers examine postoperative outcomes such as in-hospital mortality or complication rates to measure institutional performance, quality of care, and patient safety. When valid, these outcomes can be helpful to healthcare consumers, providers, regulators, insurers, and other groups who wish to discern between higher- and lower-performing institutions. There is also a trend toward aligning reimbursement for health care with the quality of care (pay-for-performance). These initiatives often operate on the premise that lower rates of certain complications or undesirable outcomes equate to higher quality care. However, the metrics used to report outcomes may not always accurately reflect the quality of care.

While there is broad support for measuring outcomes, the measurements must be accurate and based on evidence-based clinical research. For example, some groups, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, consider VTE a “never event” in certain patient groups and impose financial penalties when these hospitalized patients develop VTE [38]. This raises concern because incidence of VTE alone may not be an accurate measure of healthcare quality when many of these VTE events are truly not preventable. One recent series demonstrates that nearly half of in-hospital VTE events are not preventable, occurring in patients for whom current best-practice prophylaxis was appropriately administered [39••]. VTE prevention is effective, but the event rate cannot be zero without undue risk of bleeding and other complications [40•].

Incidence of VTE is subject to surveillance bias as previously discussed. Those developing and reviewing outcome measures for public reporting must ensure that methods and expectations for surveillance are made explicit to clinicians. Clinical guidelines are necessary to standardize frequency and modalities for screening if outcomes subject to surveillance bias, such as VTE incidence, are to be used as a performance measure. The cost of routine screening must also be considered, and the responsible payer determined, since many screening tests are not otherwise part of usual clinical care. The benefits of measuring certain outcome measures may not be worth the costs of accurately measuring that outcome through implementation of standard screening.

Linking Outcome Measures and Process Measures

One approach to performance measures could link a process of care with adverse outcomes when defining the incidence of preventable harm [41]. This may be of particular help when evaluating outcome measures where routine screening for events within the population at risk is too costly or risky. Some experts suggest that the benchmark for quality care should not focus on the outcome measure alone (such as incidence of VTE), without considering process measures (such as how frequently patients are prescribed and administered VTE prophylaxis according to best-practice guidelines) [32••, 42••, 43, 44•].

Adherence to risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis guidelines, alone or in combination with VTE incidence, may provide a more accurate measure of excellent care since this more closely estimates the true rate of preventable harm. This approach may be of help in situations where many (but not all) events are preventable and where process measures are linked to outcome measures with clear clinical evidence. This is also an intuitive approach for clinicians: to improve an outcome measure, process measures within the system of care related to the outcome of interest must be identified and addressed individually to affect improvement.

Process Measures Within the System of Care

VTE provides an important example where process measures are useful, alone or in combination with outcome measures, to determine accurate hospital performance and to improve quality of care. Evidence-based guidelines for VTE prophylaxis are available and quite effective [3••, 4••, 5, 6]. However, despite wide dissemination of these guidelines, VTE prophylaxis is commonly underutilized. One study included over 68,000 hospitalized patients at risk for VTE in 32 countries and determined that only 59 % of surgical patients and 40 % percent of medical patients received guideline-recommended VTE prophylaxis [45]. Another study demonstrated that only 42 % of US patients diagnosed with DVT during hospitalization had received VTE prophylaxis [46]. Quality improvement efforts may be more impactful if they focus on improving the system of care and the component process measures responsible for the prevention of VTE. For example, risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis is a process including assessment and prescription by a provider, administration by a nurse, and acceptance by the patient. Active strategies, including a reminder to providers to prescribe risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis for every patient as part of a standard electronic order set, are more likely to improve outcomes than passive dissemination of guidelines [12••, 47••, 48•]. Directed feedback to surgical residents of prescription failures has been shown to improve VTE ordering practices in surgery [49•]. Active attempts to understand nursing practices and beliefs can identify barriers to the administration of prescribed prophylaxis [50•]. Finally, since many patients are not aware of VTE or its potential consequences, patients may not recognize the importance of accepting prescribed prophylactic medications [51]. Attempts to engage patients in shared decision making may be fruitful to improve VTE prophylaxis nonadministration [52]. A cohesive approach to quality improvement with respect to VTE prevention may be more impactful if component process measures within the system of care are recognized and addressed individually.

Conclusion

Analysis of the current literature supports the presence of surveillance bias in currently reported outcomes related to VTE incidence: the more screening you do, the more VTE you will find. Without consensus about the role for routine screening of asymptomatic patients, performance measures likely reflect how thoroughly clinicians look for VTE and will not accurately identify the true rate of preventable harm or the quality of care. Process measures (how frequently patients are prescribed and administered risk-appropriate VTE prophylaxis) may be linked with outcome measures (VTE incidence) to estimate the true rate of preventable harm. This strategy may offer more accurate measures of performance and quality and may ultimately serve to improve patient safety.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

US Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism 2008. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Accessed December 14, 2015.

Grosse S. CDC “Incidence based cost-estimates require population based incidence data. A critique of Mahan et al.” 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/Grosse/cost-grosse-Thrombosis.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2015. Reference published within last 5 years.

Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, et al. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:7S–47. Reference published within last 5 years and considered by many to be a definitive set of guidelines for VTE prophylaxis.

Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2_suppl):e227S–77. Reference published within the last 5 years and considered by many to be a definitive set of guidelines for VTE prophylaxis.

Rogers FB, Cipolle MD, Velmahos G, Rozycki G, Luchette FA. Practice management guidelines for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: the EAST practice management guidelines work group. J Trauma. 2002;53(1):142–64.

Johanson NA, Lachiewicz PF, Lierberman JR, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on prevention of symptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(7):1756–7.

US Senate, Office of Legislative Policy and Awareness. S. Con Res. 56-Deep-vein thrombosis Awareness Month. Available at: https://olpa.od.nih.gov/tracking/109/senate_res/session1/s_con_res-56.asp. Accessed December 15, 2015.

Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, Markowitz AJ. Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2001;i-x:1–668.

Maynard G, Stein J. Preventing hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. AHRQ Publication No. 08–0075.

Maynard G. Preventing hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. AHRQ Publication No. 16-0001-EF. Reference published within last 5 years and provides comprehensive overview of practices related to prevention of VTE.

Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM, et al. The top patient safety strategies that can be encouraged for adoption now. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:365–8. Reference published within last 5 years.

Haut ER, Lau BD. Chapter 28: prevention of venous thromboembolism: brief update review. In: Making health care safer II: an updated critical analysis of the evidence for patient safety practices, vol. 211. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. p. C-62. Reference published within last 5 years and provides critical overview of patient safety practices related to prevention of VTE.

Haut ER, Schenider EB, Patel A, et al. Duplex ultrasound screening for deep vein thrombosis in asymptomatic trauma patients: a survey of individual trauma surgeon opinions and current trauma center practices. J Trauma. 2011;70(1):27–34. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Burns GA, Cohn SM, Frumento RJ, Degutis LC, Hammers L. Prospective ultrasound evaluation of venous thrombosis in high-risk trauma patients. J Trauma. 1993;35:405–8.

Napolitano LM, Garlapati VS, Heard SO, et al. Asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in the trauma patient: is an aggressive screening protocol justified? J Trauma. 1995;39:651–9.

Piotrowski JJ, Alexander JJ, Brandt CP, et al. Is deep vein thrombosis surveillance warranted in high-risk trauma patients? Am J Surg. 1996;172:210–3.

Velmahos GC, Nigro J, Tatevossian R, et al. Inability of an aggressive policy of thromboprophylaxsis to prevent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in critically injured patients: are current methods of DVT prophylaxis insufficient? J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:529–33.

Adams RC, Hamrick M, Berenguer C, Senkowski C, Ochsner MG. Four years of an aggressive prophylaxis and screening protocol for venous thromboembolism in a large trauma population. J Trauma. 2008;65:300–6.

Allen CJ, Murray CR, Meizoso JP, et al. Surveillance and early management of deep vein thrombosis decreases rate of pulmonary embolism in high-risk trauma patients. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;222(1):65–72. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Brasel KJ, Borgstrom DC, Weigelt JA. Cost-effective prevention of pulmonary embolus in high-risk trauma patients. J Trauma. 1997;42:456–62.

Cipolle MD, Wojcik R, Seislove E, Wasser TE, Pasquale MD. The role of surveillance duplex scanning in preventing venous thromboembolism in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2002;52:453–62.

Meyer CS, Blebea J, Davis Jr K, Fowl RJ, Kempczinski RF. Surveillance venous scans for deep venous thrombosis in multiple trauma patients. Ann Vasc Surg. 1995;9:109–14.

Spain DA, Richardson JD, Polk Jr HC, Bergamini TM, Wilson MA, Miller FB. Venous thromboembolism in the high-risk trauma patient: do risks justify aggressive screening and prophylaxis? J Trauma. 1997;42:463–9.

Satiani B, Falcone R, Shook L, Price J. Screening for major deep vein thrombosis in seriously injured patients: a prospective study. Ann Vasc Surg. 1997;11:626–9.

Choosing Wisely. American Board of Internal Medicine. Available at: http://www.abimfoundation.org/Initiatives/Choosing-Wisely.aspx. Accessed December 15, 2015.

Wiener RS, Ouellette DR, Diamond E, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians policy statement: the Choosing Wisely top five list in adult pulmonary medicine. Chest. 2014;145(6):1383–91. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Goy J, Lee J, Levine O, Chaudhry S, Crowther M. Sub-segmental pulmonary embolism in three academic teaching hospitals: a review of management and outcomes. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(2):214–8. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Yoo HH, Queluz TH, El Dib R. Anticoagulant treatment for subsegmental pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; CD010222. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010222.pub2. Reference published within last 5 years.

Pierce CA, Haut ER, Kardooni S, et al. Surveillance bias and deep vein thrombosis in the national trauma data bank: the more we look, the more we find. J Trauma. 2008;64:932–7.

Sackett DL. Bias in analytic research. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32(1–2):51–63.

Kardooni S, Haut ER, Chang DC, et al. Hazards of benchmarking complications with the National Trauma Data Bank: numerators in search of denominators. J Trauma. 2008;64:273–9.

Haut ER, Pronovost PJ. Surveillance bias in outcomes reporting. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2462–3. Reference published within the last 5 years and provides focused overview of surveillance bias in outcomes reporting.

Haut ER, Noll K, Efron DT, et al. Can increased incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) be used as a marker of quality of care in the absence of standardized screening? The potential effect of surveillance bias on reported DVT rates. J Trauma. 2007;63(5):1132–7.

Haut ER, Chang DC, Pierce CA, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT): hospital practice versus patient factors: an analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB). J Trauma. 2009;66(4):994–9.

Bilimoria KY, Chung J, Ju M, et al. Evaluation of surveillance bias and the validity of the venous thromboembolism quality measure. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1482–9. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Lin MY, Hota B, Khan YM, et al. CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Quality of traditional surveillance for public reporting of nosocomial bloodstream infection rates. JAMA. 2010;304(18):2035–41.

Craig SL, Feinstein AR. Antecedent therapy versus detection bias as causes of neoplastic multimorbidity. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22(1):51–6.

Streiff MB, Haut ER. The CMS ruling on venous thromboembolism after total knee or hip arthroplasty: weighing risks and benefits. JAMA. 2009;301(10):1063–5.

Haut ER, Lau BD, Kraus PS, et al. Preventability of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(9):912–5. Reference published within the last 5 years demonstrates that approximately 50 % of VTE events may not be prevented with appropriate administration of evidence-based VTE prophylaxis.

Haut ER, Lau BD, Streiff MB. New oral anticoagulants for preventing venous thromboembolism. are we at the point of diminishing returns? BMJ. 2012;344:e3820. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Pronovost PJ, Colantuoni E. Measuring preventable harm: helping science keep pace with policy. JAMA. 2009;301(12):1273–5.

Bilimoria KY. Facilitating quality improvement: pushing the pendulum back toward process measures. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1333–4. Reference published within the last 5 years and provides important argument for process measures in performance evaluation.

Tooher R, Middleton P, Pham C, et al. A systematic review of strategies to improve prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitals. Ann Surg. 2005;241(3):397–415.

Aboagye JK, Lau BD, Schneider EB, Streiff MB, Haut ER. Linking processes and outcomes: a key strategy to prevent and report harm from venous thromboembolism in surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(3):299–300. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann J, et al. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371(9610):387–94.

Goldhaber SZ, DVT FREE Steering Committee. A prospective registry of 5,451 patients with ultrasound-confirmed deep vein thrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(2):259–62.

Streiff MB, Carolan HT, Hobson DB, et al. Lessons from the Johns Hopkins Multi-Disciplinary Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Prevention Collaborative. Br Med J. 2012;344:e3935. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Haut ER, Lau BD, Kraenzlin FS, et al. Improve prophylaxis and decreased rates of preventable harm with the use of a mandatory computerized clinical decision support tool for prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in trauma. Arch Surg. 2012;147(10):901–7. Reference published within the last 5 years.

Lau BD, Arnaoutakis GJ, Streiff MB, et al. Individualized performance feedback to surgical residents improves appropriate venous thromboembolism prophylaxis prescription and reduces potentially preventable VTE: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2015. [E pub ahead of print]. Reference published within last 5 years.

Elder S, Hobson DB, Rand CS, et al. Hidden barriers to delivery of pharmacological venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: the role of nursing beliefs and practices. J Patient Saf. 2014. epub. Reference published within last 5 years.

American Public Health Association. Deep-vein thrombosis: advancing awareness to protect patient lives. Washington, DC: Public Health Leadership Conference on Deep-Vein Thrombosis; 2003.

Improving patient-nurse communication to prevent a life-threatening complication. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. 2014. Available at: http://www.pcori.org/research-in-action/improving-patient-nurse-communication-prevent-life-threatening-complication. Accessed January 7, 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Haut reports grants from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and personal fees from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, from VHA, and from Illinois Surgical Quality Improvement Collaborative. Dr. Kodadek declares no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Venous Thromboembolism After Trauma

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kodadek, L.M., Haut, E.R. Screening and Diagnosis of VTE: The More You Look, The More You Find?. Curr Trauma Rep 2, 29–34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-016-0038-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-016-0038-y