Abstract

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has made it possible to detect the in vivo concentration of positron-emitting compounds accurately and non-invasively. In order to relate the radioactivity concentration measured using PET to the underlying physiological or biochemical processes, the application of mathematical models to describe tracer kinetics within a particular region of interest is necessary. Image analysis can be performed both by visual interpretation and quantitative assessment and, depending on the ultimate purposes of the analysis, several alternatives are available. In clinical practice, PET quantification is routinely performed using the standard uptake value (SUV), a semi-quantitative index in use since the 1980s. Its computation is very simple since it requires only the PET measure at a pre-fixed sample time and the injected dose normalised to some anthropometric characteristic of the subject (generally body weight or body surface area). An alternative to the SUV is the tissue-to-plasma ratio (ratio). As its name indicates, this index is computed as the ratio between the tracer activity measured in the tissue and in the plasma pool within a pre-fixed time window. Moving from static to more informative dynamic PET acquisition, three model classes represent the most frequently used approaches: compartmental models, the spectral analysis modelling approach, and graphical methods. These approaches differ in terms of application assumptions (e.g. reversibility of tracer uptake, model structure, etc.) and computational complexity. They also produce different information about the system under study: from a macro-description of tracer uptake to a full quantitative characterisation of the physiological processes in which the tracer is involved. The application of these approaches to clinical routine is restricted by the need for invasive blood sampling. In order to avoid arterial cannulation and blood sample management, different alternative approaches have been developed for quantification of PET kinetics, including reference tissue methods. Although these approaches are appealing, the results obtained with several tracers are questionable. This review provides a complete overview of the semi-quantitative and quantitative methods used in PET analysis. The pros and cons of each method are evaluated and discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, ever since its introduction, has played an important role in the medical imaging field. Even though some have recently tried to portray PET as a “dying white elephant” [1], the technique continues to be a fundamental tool for both clinical and research applications (more than 1 million scans per year, source http://www.snm.org).

To exploit the full potential offered by this imaging modality, PET data cannot be used raw, as they are acquired and processed by the PET tomograph, but, rather, need to be quantified. Quantification of PET data is a general term that assumes a wide range of meanings, from detection of the simple concentration of the tracer in a particular region of interest (ROI) within the examined field of view to description of the rate of exchanges of different radioactive molecules within the analysed system. Irrespective of the different definitions, all PET quantification methods consist of linking the radioactivity measures detected by the scanner to the metabolic processes in which the injected radiotracer is involved, considering the specific biological characteristics of the system being investigated. Under the assumption that the tracer does not alter or perturb the system under study, it becomes possible to directly infer the in vivo system functioning.

Depending on the purpose of the PET study, different quantification methods can be employed. These approaches can be hierarchically represented using a pyramidal structure in which the level of each method represents the balance between the conditions necessary for its application and the returned data (Fig. 1). Static (single-frame acquisition) and dynamic (multi-frame acquisition) are the two classic PET experimental frameworks (Fig. 2). Static PET imaging is used mainly for clinical applications due to its feasibility (reasonable costs and easy patient management). The principal areas of application are in oncological and cardiac imaging, in which 90 % of all annual PET studies are performed (source http://www.snm.org). Dynamic PET studies are instead used in research and in particular neuroscience research. In fact, despite the recent massive development of magnetic resonance imaging, PET continues to be the standard for investigating tissue metabolism (see, for example, [2]). Very often dynamic studies are coupled with blood sampling, which represents one of the most important limitations for the use of these studies in clinical routine.

This review sets out to provide more than a simple list of PET data analysis methods. Indeed, its aim is to offer an overview of the advantages and limitations of the different alternatives available for PET quantification in order to allow the most appropriate solutions to be chosen for any given needs.

Semi-quantitative indices

Standardised uptake value

The standardised uptake value (SUV) is the most widely used semi-quantitative index for PET quantification in clinical practice [3]. Application of the SUV in PET dates back to 1985 when it was proposed as a semi-quantitative index in oncological studies [4]. The SUV provides an index of tracer uptake in a ROI or voxel of interest, normalised to the injected dose and to a normalisation factor (NF) based on the subject’s anthropometric characteristics:

where the radiotracer concentration (e.g. kBq/ml) indicates the concentration measured with PET over a short interval (usually from 5 to 15 min) after a pre-defined time has been allowed to elapse following tracer administration (e.g. 45 or 60 min). The injected dose (e.g. MBq) is the total administered dose and the most common NFs are body weight (expressed in kg), body surface area (in m2 [5]), and lean body mass (in kg [6]). The simplicity and versatility of the SUV make it suitable for clinical routine, as it can be used with a variety of PET tracers and does not require any arterial cannulation. Widely applied in oncology for diagnosis and tumour staging, it has been shown to be effective in assessment, especially using [18F]FDG, of the response to therapy in various type of cancer (lung [7], breast [8], ovarian [9]).

Nevertheless, several factors (both physiological and technical, as discussed extensively by Boellard and colleagues [3]), can affect SUV calculation. Therefore, a priori validation of the SUV is always necessary: given a particular tracer and a system of interest, it is necessary to validate SUV reproducibility, its consistency with the tracer kinetics and physiology, and its ability to differentiate healthy from non-healthy tissues [10].

Ratio methods

Another PET quantitative index is provided by the ratio method [11]. In PET, the volume of distribution V T (ml of plasma/cm3 of tissue) is defined as the ratio at true equilibrium between the tracer concentration in tissue [C tissue, (kBq/cm3)] and the tracer concentration in plasma [\( C_{\text{p}} \), (kBq/ml)]. True equilibrium can be reached only by delivering the radioactive tracer as an infusion (or, to reduce the time needed to reach equilibrium, as an initial bolus followed by a constant infusion). In this way, V T can be measured directly from the tissue-to-plasma concentration ratio [11–13]. This infusion protocol requires two to three times as much radioligand as a single-bolus protocol, and the optimal duration of the scanning time must be determined beforehand [14].

Although equilibrium is not reached in a single-bolus injection protocol, a constant ratio of tissue-to-plasma radioactivity is often maintained over time and thus the ratio method can be used to provide a semi-quantitative description of tracer kinetics. In reversible PET tracers, i.e. tracers that are never trapped in a specific metabolic state within a specific tissue volume, this approach results in the estimation of the apparent volume of distribution (\( V_{\text{app}} \)), which is different from V T (\( V_{\text{app}} > V_{\text{T}} \)) [15]. The magnitude of this overestimation depends on the rate of plasma clearance and the local tissue kinetics [11], but for tracers with very slow plasma clearance this method provides acceptable estimates of V T [12].

Similarly, when applied to the late time points in a PET experiment involving an irreversible tracer, such as [18F]FDG, the ratio method has shown to correlate well with tracer trapping [16].

In receptor studies, the ratio method is often used to estimate binding potential BPND (unitless). This parameter, compared to V T, is more informative since it reflects the actual density of available receptors and the tracer–receptor affinity [17]. The ratio method estimates BPND by using the concentration of tracer in tissue and in a reference region without specific binding, thus avoiding arterial sampling [18, 19]. The ratio method can be used considering the tracer concentration at a point in time (peak equilibrium) or with the integral of the tracer over time (interval method) [19, 20]. For different receptor tracers, the ratio method has been shown to give values that are highly correlated with BPND estimates obtained using the gold standard quantitative approach; i.e. compartmental modelling (see section on compartmental modelling).

Graphical analysis

The graphical methods are approaches that apply a transformation of the data such that, after a certain time, the data show a linear trend whose slope can be related to the parameter of interest. Graphical methods exploit the status of equilibrium that is reached between the reversible exchanges in the system after a certain amount of time from tracer injection. The two main graphical approaches are the Patlak plot [21] and the Logan plot [22]. These are the simplest dynamic quantification approaches and, since the slope can be derived with a non-iterative linear estimator, they are appropriate for analyses at voxel level, thus producing a functional image of the parameter of interest (parametric map). On the other hand, it must be noted that they neither account for blood volume nor provide any insight regarding tracer kinetic behaviour [14, 23].

Patlak plot (irreversible tracers): originally developed for quantification of [18F]FDG PET studies [21], the Patlak plot returns, as a unique parameter, K i (ml/cm3/min), the irreversible uptake rate constant in tissue. The Patlak plot is given by the expression:

It requires fulfilment of just a few hypotheses, namely the presence of an irreversible compartment and a time t* after which all the reversible system compartments are equilibrated with the plasma (i.e. the plot becomes linear, Fig. 3a). The choice of t* is critical and it can affect the final estimates [24].

Patlak and Logan plots. The figure shows an example of a Patlak plot (a) and an example of a Logan plot (b) with plasma input function. The graphical analyses refer to an irreversible ([18F]FDG) and reversible ([11C](R)-rolipram) tracer, respectively. The data show a linear trend after the equilibration time t* and the slope corresponds to the estimated parameter of interest (K i for the Patlak plot and V T for the Logan plot)

Logan plot (reversible tracers): originally developed for quantification of reversible neuroreceptor ligands, it allows estimation of V T from the slope of the transformed data (Fig. 3b) [22]. The Logan plot is given by the expression:

The choice of t* is critical for the Logan plot, too, and it must be made by visually analysing the graphical plot.

Contrary to the Patlak method, Logan estimates are affected by noise-dependent bias (due to the transformation of the data that introduces a statistical error term in both plot variables that become highly correlated) [14]. As a result, the method tends to underestimate V T when the data are noisy, especially at the voxel level [23]. Over the years different techniques to reduce this bias have been proposed in the literature, implementing data smoothing, different estimators, or rearrangement of the Logan plot equation. All these techniques nevertheless require definition of the equilibration time t*.

A first alternative was the generalised linear least square (GLLS, [25]) method, proposed as an iterative technique to smooth the tissue curve prior to application of the Logan plot [26]. Despite having been shown to reduce the noise-related bias [26], the method requires the definition of a model structure, and thus loses the advantage of being a model-independent approach. Another method using pre-smoothing of the images was proposed in [27]: with this method, principal component analysis is applied before application of the reference Logan plot (see “Graphical methods with reference region” section). This approach reduces the noise but it is sensitive to the number of components selected for the pre-processing (too high a number can reintroduce the bias).

To reduce the underestimation associated with the least square estimator, two different estimators were proposed [28, 29]. However, these approaches were shown to only partially remove the bias [30], or to be sensitive to the initial values and the convergence criteria [29].

Several rearrangements of the Logan plot equation were proposed: multilinear analysis [30], the likelihood estimation in graphical analysis (LEGA) [31], the maximum a posteriori estimation in graphical analysis (MEGA) [32], and the empirical Bayesian estimation in graphical analysis (EBEGA) [33]). All these methods make it possible to reduce the underestimation, but at a cost. Indeed, when applied at the voxel level their parameter estimates are characterised by a high between-voxel variance and they are either sensitive to the prior knowledge (MEGA, EBEGA) or require the use of a non-linear estimator (LEGA), with all the issues related to the convergence of the method and the computational heaviness when applied at the voxel level.

Another alternative to the Logan plot was the relative equilibrium (RE) plot proposed in [34]. However, this method requires two conditions to be fulfilled explicitly, i.e. the tissue-to-plasma ratio has to be constant and the plasma has to be mono-exponential after the equilibration time, which therefore limits application of the method [29].

For situations in which these two conditions are not met, a multiple graphical approach was proposed, consisting of the RE plot followed by the Patlak plot (RE-GP analysis) [35], where V T is obtained by combining the slope of the two plots.

Graphical methods with reference region

In receptor studies, when the plasma activity curve is not available but a tissue region void of specific receptors is present, both the Patlak plot and the Logan plot can be adapted to use the reference region instead of the plasma information as input. As for the plasma input versions, the graphical reference approaches, too, require definition of t*, after which the plots become linear.

Patlak plot (irreversible kinetics): the Patlak plot with a reference tissue input [36] is given by:

where C ref(t) is a reference tissue region where the tracer is not irreversibly trapped but also achieves equilibrium with plasma, and V′T and V′b are the volume of distribution and the blood volume of the reference region.

Logan plot (reversible kinetics): the Logan plot with a reference tissue input [37] returns the distribution volume ratio (DVR, i.e. the ratio of the V T in the target tissue to the reference V′T) by:

where C ref(t) is a reference tissue region with an average tissue-to-plasma efflux constant \( \bar{k}_{2}^{\text{REF}} \) and V′T is the reference region volume of distribution.

From the DVR it is possible to derive the binding potential, BP, as \( {\text{DVR}} - 1 \) (i.e. the slope of the graphical plot minus 1).

In this version of the Logan plot, it is necessary to fix, a priori, a value for \( \bar{k}_{2}^{\text{REF}} \) from previous studies with plasma sampling. However, when the ratio of \( C_{\text{tissue}} (t) \) over \( C_{\text{ref}} (t) \) is reasonably constant or when the receptor density is low, the term containing the \( \bar{k}_{2}^{\text{REF}} \) can be omitted [37].

Spectral analysis methods

Dynamic PET data can be quantified by using spectral analysis (SA) [38]. In SA (also known as exponential spectral analysis) the concentration of radioactivity in the tissue at time t, C tissue(t), is modelled through the convolution of the plasma tracer time–activity curve, C p(t), with the sum of M + 1 distinct exponential terms as:

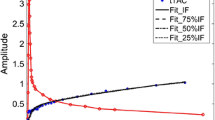

where α j and β j (β 1 < β 2 < ··· < β M ) are assumed to be real-valued and non-negative. This formulation consists of decomposition of the measured radioactivity time-course on a pre-defined basis of kinetics components (\( C_{\text{p}} \left( t \right) \otimes e^{{ - \beta_{j} t}} \)), whose amplitudes (α j ) are unknown and need to be estimated from the data [38, 39] (Fig. 4a). Although the term is usually associated with frequency domain analysis, in this context SA is so-called because it provides a “kinetic spectrum” representing the functional processes in which the investigated tracer is involved, independently of any specific model configuration. Hence, from this spectrum it is possible to obtain a complete description of tracer kinetics as well as to identify the number and the type of compartments necessary for the data modelling [38, 39].

Quantification of dynamic PET data using spectral analysis: the figure shows a representative kinetic spectrum (a) with the corresponding model-fit of the data (b). For the particular case, among the 100 components allowed by the spectral functional basis, only three (blue, green and red lines, respectively) are estimated from the data. All the remaining coefficients are not present because they are estimated at zero. It is to be noted that the spectral components assume different meanings depending on the position of the beta grid where they are located. For example, the corresponding terms for β very large (β → ∞), become proportional to \( C_{\text{p}} (t) \), and can be seen as “high-frequency” components, representing the blood contribution to the measured activity when not explicitly modelled. In the same way, the corresponding term with β = 0 can be viewed as the “low-frequency” component, i.e. accounting for trapping of the tracer. Components with intermediate values of β (“equilibrating components”) reflect tissue compartments that exchange material directly or indirectly with the plasma with their number corresponding to the number of identifiable tissue compartments within the region of interest (color figure online)

For its application SA requires the fulfilment of certain conditions, i.e. the presence of a single input in the experiment or the absence of complete cycling connections in the system of interest [40]. These conditions are very common, even considering the wide range of PET tracers, and therefore do not represent a major limitation for SA applicability [40].

Quantification of dynamic PET data

From the estimated spectral components, i.e. the estimated α j and β j , it is possible to derive important physiological information, such as the influx rate constant (K 1, ml/cm3/min), the net uptake of the tracer (when dealing with irreversible tracers) in the tissues K i , and the volume of distribution V T (when dealing with reversible tracers). For a detailed mathematical formalisation of K 1, K i and V T in the context of SA interested readers are referred to [41].

In addition to these parameters, if the measurement equation for the total radioactivity measured by the PET scanner takes into account the tracer contribution in both blood and tissues, it is also possible to derive the blood volume (V b, unitless). Generally, this corresponds to the case in which

where \( C_{\text{measured}} \left( t \right) \) represents the total activity measured by the scanner within a specified volume of observation, \( C_{\text{tissue}} \left( t \right) \) represents the tissue kinetic activity and C b(t) the blood tracer activity. V b is an interesting parameter because it provides an indirect measure of the integrity of the blood vasculature surrounding the target tissues. Variation from the range of normal healthy tissue values might be used to characterise damage or impairments in blood-to-tissue transport.

Compared to graphical approaches, SA presents some additional important advantages: (1) SA can return multiple kinetic parameters rather than just K i or V T; (2) SA makes it possible to account for the vascular tracer presence within the ROI or voxel (unlike SUV, and the Patlak and Logan approaches); (3) it returns the model-fit of the measured data (Fig. 4b); (4) SA can be applied to heterogeneous as well as the homogeneous tissues, providing a measure of the tissue heterogeneity [40]. This characteristic is particularly useful for tracer kinetics studies where the limited spatial resolution of the PET scanner captures a heterogeneous mixture of kinetically dissimilar tissues within the field of view. In PET brain studies, for example, it is not uncommon to have a combined signal from grey and white matter, especially in cortical regions [41]. If this feature is not taken into account, data analysis can lead to biased results. Moreover, measuring heterogeneity has been demonstrated to be a valuable tool for tissue characterisation. In oncological PET studies, for example, tumour kinetic heterogeneity has been shown to be linked to the tumour metabolism as well as to be predictive of individual therapy response [42, 43].

Applications

The SA model was first applied on brain PET datasets, specifically for the evaluation of cerebral blood flow, cerebral glucose utilisation and opiate receptor ligand binding. H 152 O, [18F]FDG and [11C]DPN PET data were considered for this purpose. Since these attempts, the SA model has been widely used in a large variety of testing conditions, with different implementative settings regarding the number and distribution of betas as well as the inclusion of a trapping component in the model formulation. SA has been applied to preclinical (rats and rabbits) [44, 45] as well as to clinical data. Most of its applications are related to the investigation of brain neuroreceptors [39, 46–48] or enzymes [49, 50] even though SA has also been applied to PET studies involving the heart [51], skeletal leg muscle [52, 53], breast cancer [54] and gastrointestinal cancer [55]. Most of these applications aimed to exploit spectral-based procedures to overcome the limits of the standard quantification methodologies.

Limitations and filter versions

The SA method is well known to be sensitive to noise in the data, with the bias being highly dependent on the level of noise present [39, 46, 56]. For this reason, over the years several strategies have been proposed in the literature to lessen the impact of data noise on the estimated spectra and on parameters of interest.

Among the different alternatives, the most widely used solutions are rank-shaping spectral analysis (RSSA) [57] and spectral analysis with iterative filter (SAIF) [58]. Unlike the standard SA approach, these two methods were developed for reversible and irreversible tracers, respectively. RSSA and SAIF have been shown to return high-quality parametric images even in high-noise PET data acquisitions [47–49, 59]. These solutions are available to the public, through a licence-free graphic-based software tool available at http://bio.dei.unipd.it/sake [60].

Model development

In addition to tissue kinetic quantification, SA has been used as model development tool for use with several PET tracers [51, 52, 61]. Modelling a system is important because it helps to shed light on the system’s mechanisms of functioning in healthy as well as pathological conditions. SA has been shown to be particularly useful when new PET tracers are analysed for the first time. In this context, the method offers the possibility of determining the number and type of compartments present in a system, and of distinguishing between reversible and irreversible exchanges. It is important to note that with SA it is impossible to determine an unequivocal correspondence between the spectrum and its equivalent model because nothing can be derived about the system interconnections. On the other hand, from a particular estimated spectrum, it is possible to associate a class of equivalent model configurations that share the same number of compartments (Fig. 5). In such cases, it is possible to choose the configuration that is most suitable for describing the kinetics of the tracer under study, exploiting physiological knowledge of the system being investigated. This procedure is theoretically always applicable, but may not be advisable in real practice. It very often happens that the presence of noise in the data (especially for voxel-wise analysis) produces a biased number of SA-estimated components (generally higher than the true value) leading toward an erroneous class of model configurations [51]. For this reason, when the purpose of SA application is model development, it is preferable to define, a priori, a set of model alternatives (by fixing the number of exponentials to a pre-defined range of values), identify each of them, and then select the one that best describes the data. This approach is also called non-linear SA (NLSA), underlining the different type of estimator employed by the method [51]. Compared with standard SA, NLSA offers several advantages. First of all it returns not only the standard deviation error of the α j estimates, but also the precision of the β j . This information can be combined with the parsimony criteria, such as Akaike or Bayesian information criterion, for selection of the best model. Second, estimation of the β j within a pre-fixed compartmental structure avoids the problem of the extra components seen in the standard SA. For all these reasons NLSA represents the most appropriate SA approach for model identification.

Spectral analysis application for model development: the figure shows the association of a representative estimated spectrum (a) with its consistent compartmental model configurations (b, c). The example demonstrates how, even for a simple kinetic spectrum (one trapping and one reversible component), it is not possible to guarantee a unique correspondence between the two types of representation

Compartmental modelling

Compartmental modelling [62] is the most challenging step in quantitative PET, since it attempts to unveil the mechanisms of functioning of the investigated system. Unlike the other quantitative approaches presented above, compartmental modelling requires a full mathematical description of the system processes. It follows that compartmental modelling is the only approach that allows a full understanding of the physiological system itself and/or of the pathogenesis of a disease.

Notably, compartmental modelling represents the basis of PET quantification (the bottom of the pyramid in Fig. 1). This is because all the simpler quantitative methods presented above are based on a compartmental description of the PET tracer kinetics.

The three most important compartmental models in PET

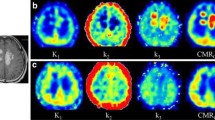

Compartmental models have a large tradition in quantitative PET imaging since the pioneering article of Dr. Sokoloff and colleagues [63] in 1977 in which they presented the theoretical basis of the well-known two-tissue compartment model used to quantify [18F]FDG brain studies. Sokoloff’s model (Fig. 6a), the one-tissue two-parameter model (developed on the basis of Kety studies [64] (Fig. 6b) for the quantitative assessment of blood perfusion), and the two-tissue four-parameter model (developed by Mintun and colleagues [65] (Fig. 6c) for receptor ligand binding studies) are the most important and relevant models used in PET to derive and quantify physiological information in absolute measurement units. More specifically, they make it possible to obtain the fractional metabolic rate of glucose, [18F]FDG tracer phosphorylation velocity, the inflow and outflow tracer velocities between the plasma and tissue space, blood perfusion measure, and the BP. These models were developed for brain PET imaging, but since then they have been extended to other biological apparatuses outside the brain (e.g. [52, 54]).

The most widely used compartmental models in quantitative PET together with their macroparameters. Each model is a combination of different compartments (circles) while the arrows indicate material fluxes between compartments due to transport or to a chemical transformation or both. Panel A the two-compartment three-rate constant model for quantifying [18F]FDG glucose analogue as proposed by Dr. Sokoloff and colleagues [63] in 1977. Its three microparameters are: K 1 (ml/cm3/min) and k 2 (min−1), the rate constants of [18F]FDG forward and reverse transcapillary membrane transport, and k 3(min−1), the rate of [18F]FDG phosphorylation. From the microparameters, one can obtain the macroparameters listed in the same panel. Panel B the one-compartment two-rate constant model for quantifying blood perfusion as proposed by Kety [64]. Its two microparameters are: K 1 (ml/cm3/min), blood perfusion, and k 2 (min−1), as originally defined by Kety, blood perfusion divided by the partition coefficient or, as also used in PET literature, the volume of distribution of the tracer. Panel C the two-compartment four-rate constant model used for quantifying PET receptor studies. Its four microparameters are: K 1(ml/cm3/min), the transport rate of ligand from plasma to tissue, k 2(min−1), the transport rate of ligand from tissue to plasma, k 3 (min−1) and k 4 (min−1), the transport rates between free and specifically bound ligand in tissue

A few definitions

Each circle in Fig. 6 represents a compartment, i.e. an amount of well-mixed and kinetically homogeneous material [62], while the arrows indicate a flux of material from one compartment to another due to transport or to a chemical transformation or both. A generic compartmental model is, thus, a model consisting of a finite number of compartments, each mathematically described by a system of first-order time-dependent differential equations. The time-dependence of the equations naturally makes it necessary to acquire dynamic PET images in order to appropriately obtain physiological information from a tissue ROI or voxel image unit.

Compartmental model outcomes

The use of the dynamic PET images and of arterial plasma samples makes it possible to estimate the model parameters (K 1, k 2, \( k_{3} \) and \( k_{4} \) in Fig. 6), frequently referred to, in PET literature, as microparameters. Note that in the PET literature K 1 is often reported using a capital k to denote a different unit of measurement (ml/cm3/min or \( {\text{ml}}_{\text{plasma}} \)/\( {\text{ml}}_{\text{tissue}} \)/min) from that of the other microparameters in Fig. 6 (\( { \hbox{min} }^{ - 1} \)). From the microparameters, one can also derive the macroparameters of interest (Fig. 6). Thanks to its ability to estimate both micro- and macro-parameters, compartmental modelling is necessarily applied to understand whether simpler quantitative approaches, such as SUV or graphical methods, are able to derive reliable and physiologically informative macroparameters for a specific tracer in a specific tissue.

How to obtain microparameter estimates

The gold standard mathematical approach for the quantification of the model microparameters is the weighted non-linear least squares estimator. Weights are defined as the inverse of the variance of the PET measurement error. To estimate the variance, there are several formulas and one of the most widely used is [66]:

where \( C (t_{k} ) \) represents the acquired mean value of the tracer activity over the kth relative time scan interval \( \Delta t_{k} \).

Note that when dealing with very noisy data, such as those at voxel level, this estimator presents several disadvantages such as convergence issues, high computational time and sensitivity to initial estimates. Therefore, the non-linear estimator can be efficiently applied only when the study is limited to regions of interest. Thus, when the aim is to numerically identify the microparameters of a compartmental model at the voxel level, a different estimator from the gold standard must be considered (see ROI versus voxel-level analysis section).

Non-invasive approaches

For standard graphical methods, SA and compartmental modelling, knowledge of the tracer arterial plasma mass/concentration over the PET experimental time is required as an input function of the model. This, of course, is not a trivial requirement since it implies discomfort for the patient and invasive and expensive procedures for the analysis of numerous blood samples. It is also necessary to describe, over the experimental time, the arterial blood tracer, the arterial tracer metabolites and, finally, the plasma arterial tracer kinetics free from metabolites (C p(t) in Fig. 6).

It is evident that due to their complexity (dynamic PET imaging and blood measurements), quantitative approaches are suitable for research PET studies but in general not applicable in clinical studies, where simpler approaches are required. The main problem to overcome to make quantitative PET studies more attractive is the requirement of arterial catheterisation. Several attempts have been made to derive the required Cp(t) information directly from the images. Unfortunately, interesting results were obtained only with PET tracers that do not produce any metabolites, such as [18F]FDG. In fact, image-derived input functions contain the whole-blood positron emitter concentration, and without additional information it is not possible to separate the parent compound from its radioactive metabolites and the plasma radioactivity from the whole-blood kinetics. In particular, only a few tracers do not have metabolite products, [18F]FDG being the most notable example. Thus, the image-derived plasma input function is currently used mainly in [18F]FDG dynamic PET studies, where it is extracted from large blood pools, such as the heart [24], the aortic segments [67], and the femoral arteries [68]. Carotid areas are used for brain studies, however, they are challenging [69]. Notably, motion artefacts and a non-optimal time frame are both additional confounding effects for a reliable image-derived input function. Another limitation is that these methods do not allow a correct estimation of the initial part of the curve. Therefore, their use in practice is restricted to graphical approaches, as methods that rely on the exact shape of the input function (such as compartmental modelling or SA) are more likely to yield erroneous estimates.

Population-derived input function is probably the most interesting approach for use in clinical practice with a large number of PET tracers. A population-based input function is commonly obtained by averaging a set of input functions, normalised to the injected dose invasively obtained by using arterial catheterisation. The principal assumption is that the kinetics of the plasma arterial input function exhibits low between-subjects variability both in healthy and in pathological subjects. Another assumption is that the duration of the tracer injection infusion used in the cohort of subjects that one wants to analyse must match the injection protocol used in the group of subjects considered for the calculation of the population-derived input function. Both assumptions are crucial to make kinetic modelling results reliable. Unfortunately, the population-based input function approach has been validated almost exclusively for [18F]FDG [70], whereas few attempts have been made with other tracers [71].

Another appealing approach to avoid arterial catheterisation in PET quantification is the use of a ROI as input function [72]. However, while this approach is widely used in brain receptor studies, it is difficult to extend reference region definition to studies not involving receptor systems.

Other approaches have been less extensively evaluated, including the use of venous instead of arterial samples, but, to date, quantification without arterial catheterisation remains a challenge, with the sole (albeit significant) exception of [18F]FDG and reference receptor studies.

ROI versus voxel-level analysis: pros and cons

In quantitative PET data analysis, computation of the physiological information can be performed either at region level or at voxel level. ROI analysis clearly leads to more robust results since the average of the voxel information in the ROI is used, allowing a dramatic noise reduction, especially in the case of dynamic PET studies. When the analysis is performed at voxel level, parametric maps are generated and these, because of their high spatial resolution, can be very important. Phenomena such as a lesion in a small area of an anatomical structure may be invisible on ROI analysis, whereas they may be rendered evident, even on simple visual inspection, by parametric maps. However, time–activity curves derived from a voxel are characterised by a low signal-to-noise ratio. This makes the use of non-linear estimators difficult and unwieldy because of their computational cost, the convergence issues and the sensitivity to initial estimates. Thus, more robust and faster estimation algorithms are needed. Various approaches are available for quantification at voxel level, such as the GLLS method [25], basis function methods [73–75], and global two-stage [76], and multi-scale hierarchical Bayesian approaches [77].

Integrative approaches were also developed to combine estimation of kinetic microparameters with a 4D image reconstruction algorithm with the aim of reducing the noise-induced bias and the variance of the kinetic estimated values, compared with traditional post-reconstruction analysis results [78, 79].

Whether working at voxel or at ROI level, quantitative PET imaging is prone to several confounding effects that can limit the reliability of the estimates. One of these is the error introduced by patient movement that results in blurred images with degraded spatial resolution, which can be a serious problem when thorax studies are evaluated. Current motion correction methods are based on algorithms for image registration and/or hardware motion tracking using an external measurement device. However, there exists no common approach suitable for all types of PET study. Thus, even if motion correction analysis is well defined in brain studies and validated algorithms of co-registration can be applied, the motion correction procedures outside the brain still need to be standardised.

Partial volume is a second problem that affects ROI-based analysis but also, albeit with a less dramatic impact, voxel-based quantitative results. Here, the term partial volume refers to the possible presence of tissue heterogeneity within a single voxel or ROI. This presence makes quantification via mathematical modelling more complex (potentially confounding) [80].

Spillover activity is the third major problem when dealing with PET images. The amount of radioactivity measured in the ROI or voxel could be overestimated due to presence of very specific and high tracer activity in the surrounding tissues. Several strategies exist to correct for the spillover effect. These are typically computationally demanding, and can require a very detailed anatomical MR image and robust a priori knowledge of the tracer distribution [81].

Conclusions

In PET imaging, the amount of information that can be obtained from a study is directly proportional to the experimental complexity (dynamic/static PET imaging, blood measurements, etc.) and the quantification method used.

Several approaches are available for the quantification of PET data, and integration of data from multiple methods can strengthen the validity of the results obtained. Therefore, the different approaches described in this review must be considered to be complementary, rather than in competition.

The interpretation of the results is a critical step which requires particular care. Reliability, accuracy and consistency of the parameter estimates with the physiology always have to be verified a posteriori. Notably every quantification method requires the application of some assumptions. It is mandatory always to verify that the results obtained do not contradict these assumptions. In particular, even though it is sometimes preferred to implement simpler methods (such SUV, ratio or graphical analysis), it must be remembered that only compartmental modelling allows a full understanding of the physiological system. Moreover, all the simpler quantitative approaches need to be validated, prior to application, for each single tracer and for each body region.

In the coming years, simultaneous PET/MR imaging studies are expected to have a widespread impact within the scientific community, even though the numerous technical challenges are still being addressed [82]. Thus, new methodologies combining analysis of these two modalities are expected to be developed. Similarly, integration of PET imaging with genomics and proteomics [83] as well as with other non-imaging methods might further extend the applicability of PET, especially for research purposes. It will be important to introduce novel radiotracers to target, for instance, specific cancer-related receptors or antigens, for which the present kinetic quantification approaches might not be appropriate; this will require new model development.

References

Cumming P (2014) PET neuroimaging: the white elephant packs his trunk? Neuroimage 84:1094–1100

Gunn RN, Rabiner EA (2013) PET neuroimaging: the elephant unpacks his trunk: comment on cumming: “PET neuroimaging: The white elephant packs his trunk?”. Neuroimage 94:408–410

Boellaard R (2009) Standards for PET image acquisition and quantitative data analysis. J Nucl Med 50(Suppl 1):11s–20s

Kubota K, Matsuzawa T, Ito M, Ito K, Fujiwara T, Abe Y, Yoshioka S, Fukuda H, Hatazawa J, Iwata R et al (1985) Lung tumor imaging by positron emission tomography using C-11 l-methionine. J Nucl Med 26(1):37–42

Du Bois D, Du Bois EF (1916) A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 17:863–871. doi:10.1001/archinte.1916.00080130010002

Zasadny KR, Wahl RL (1993) Standardized uptake values of normal tissues at PET with 2-[fluorine-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose: variations with body weight and a method for correction. Radiology 189(3):847–850

Hickeson M, Yun M, Matthies A, Zhuang H, Adam LE, Lacorte L, Alavi A (2002) Use of a corrected standardized uptake value based on the lesion size on CT permits accurate characterization of lung nodules on FDG-PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 29(12):1639–1647

Ulaner GA, Eaton A, Morris PG, Lilienstein J, Jhaveri K, Patil S, Fazio M, Larson S, Hudis CA, Jochelson MS (2013) Prognostic value of quantitative fluorodeoxyglucose measurements in newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Med 2(5):725–733

Rockall AG, Avril N, Lam R, Iannone R, Mozley PD, Parkinson C, Bergstrom DA, Sala E, Sarker SJ, McNeish IA, Brenton JD (2014) Repeatability of quantitative FDG-PET/CT and contrast enhanced CT in recurrent ovarian carcinoma: test retest measurements for tumor FDG uptake, diameter and volume. Clin Cancer Res 20:2751–2760

Tomasi G, Turkheimer F, Aboagye E (2012) Importance of quantification for the analysis of PET data in oncology: review of current methods and trends for the future. Mol Imaging Biol 14(2):131–146

Carson RE, Channing MA, Blasberg RG, Dunn BB, Cohen RM, Rice KC, Herscovitch P (1993) Comparison of bolus and infusion methods for receptor quantitation: application to [18F]cyclofoxy and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 13(1):24–42

Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, al-Tikriti, Baldwin RM, Zea-Ponce Y, Zoghbi SS, Charney DS, Hoffer PB, Innis RB (1994) SPECT quantification of [123I]iomazenil binding to benzodiazepine receptors in nonhuman primates: II. equilibrium analysis of constant infusion experiments and correlation with in vitro parameters. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 14(3):453–465

Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Kume A, Albin R, Kilbourn MR, Kuhl DE (1997) Equilibrium versus compartmental analysis for assessment of the vesicular monoamine transporter using (+)-alpha-[11C]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 17(9):919–931

Slifstein M, Laruelle M (2001) Models and methods for derivation of in vivo neuroreceptor parameters with PET and SPECT reversible radiotracers. Nucl Med Biol 28:595–608

Lehtio K, Oikonen V, Nyman S, Gronroos T, Roivainen A, Eskola O, Minn H (2003) Quantifying tumour hypoxia with fluorine-18 fluoroerythronitroimidazole ([18F]FETNIM) and PET using the tumour to plasma ratio. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30(1):101–108

van den Hoff J, Oehme L, Schramm G, Maus J, Lougovski A, Petr J, Beuthien-Baumann B, Hofheinz F (2013) The PET-derived tumor-to-blood standard uptake ratio (SUR) is superior to tumor SUV as a surrogate parameter of the metabolic rate of FDG. EJNMMI Res 3(1):77

Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN, Holden J, Houle S, Huang SC, Ichise M, Iida H, Ito H, Kimura Y, Koeppe RA, Knudsen GM, Knuuti J, Lammertsma AA, Laruelle M, Logan J, Maguire RP, Mintun MA, Morris ED, Parsey R, Price JC, Slifstein M, Sossi V, Suhara T, Votaw JR, Wong DF, Carson RE (2007) Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27(9):1533–1539

Farde L, Eriksson L, Blomquist G, Halldin C (1989) Kinetic analysis of central [11C]raclopride binding to D2-dopamine receptors studied by PET–a comparison to the equilibrium analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 9(5):696–708

Ito H, Hietala J, Blomqvist G, Halldin C, Farde L (1998) Comparison of the transient equilibrium and continuous infusion method for quantitative PET analysis of [11C]raclopride binding. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 18(9):941–950

Ginovart N, Wilson AA, Meyer JH, Hussey D, Houle S (2001) Positron emission tomography quantification of [(11)C]-DASB binding to the human serotonin transporter: modeling strategies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21(11):1342–1353

Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD (1983) Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 3(1):1–7

Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann R, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ (1990) Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(-)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 10:740–747

Laruelle M, Slifstein M, Huang Y (2002) Positron emission tomography: imaging and quantification of neurotransporter availability. Methods 27(3):287–299

Choi Y, Hawkins RA, Huang SC, Gambhir SS, Brunken RC, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR (1991) Parametric images of myocardial metabolic rate of glucose generated from dynamic cardiac PET and 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose studies. J Nucl Med 32(4):733–738

Feng D, Huang SC, Wang X (1993) Models for computer simulation studies of input functions for tracer kinetic modeling with positron emission tomography. Int J Biomed Comput 32(2):95–110

Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Ding YS, Wang GJ, Alexoff DL (2001) A strategy for removing the bias in the graphical analysis method. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21(3):307–320

Joshi A, Fessler JA, Koeppe RA (2008) Improving PET receptor binding estimates from Logan plots using principal component analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28(4):852–865

Varga J, Szabo Z (2002) Modified regression model for the Logan plot. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22(2):240–244

Logan J, Alexoff D, Fowler JS (2011) The use of alternative forms of graphical analysis to balance bias and precision in PET images. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31(2):535–546

Ichise M, Toyama H, Innis RB, Carson RE (2002) Strategies to improve neuroreceptor parameter estimation by linear regression analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22(10):1271–1281

Ogden RT (2003) Estimation of kinetic parameters in graphical analysis of PET imaging data. Stat Med 22:3557–3568

Shidahara M, Seki C, Naganawa M, Sakata M, Ishikawa M, Ito H, Kanno I, Ishiwata K, Kimura Y (2009) Improvement of likelihood estimation in Logan graphical analysis using maximum a posteriori for neuroreceptor PET imaging. Ann Nucl Med 23(2):163–171

Zanderigo F, Ogden RT, Bertoldo A, Cobelli C, Mann JJ, Parsey RV (2010) Empirical Bayesian estimation in graphical analysis: a voxel-based approach for the determination of the volume of distribution in PET studies. Nucl Med Biol 37:443–451

Zhou Y, Ye W, Brašić JR, Crabb AH, Hilton J, Wong DF (2009) A consistent and efficient graphical analysis method to improve the quantification of reversible tracer binding in radioligand receptor dynamic PET studies. NeuroImage 44(3):661–670

Zhou Y, Ye W, Brasic JR, Wong DF (2010) Multi-graphical analysis of dynamic PET. Neuroimage 49(4):2947–2957

Patlak CS, Blasberg RG (1985) Graphical evaluation o of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 5(4):584–590

Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL (1996) Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16(5):834–840

Cunningham VJ, Jones T (1993) Spectral analysis of dynamic PET studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 13(1):15–23

Turkheimer FE, Moresco RM, Lucignani G, Sokoloff L, Fazio F, Schmidt K (1994) The use of spectral analysis to determine regional cerebral glucose utilization with positron emission tomography and [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose: theory, implementation, and optimization procedures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 14(3):406–422

Schmidt K (1999) Which linear compartmental systems can be analyzed by spectral analysis of PET output data summed over all compartments? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 19(5):560–569

Schmidt KC, Turkheimer FE (2002) Kinetic modeling in positron emission tomography. Q J Nucl Med 46:70–85

Willaime JM, Turkheimer FE, Kenny LM, Aboagye EO (2013) Quantification of intra-tumour cell proliferation heterogeneity using imaging descriptors of 18F fluorothymidine-positron emission tomography. Phys Med Biol 58(2):187–203

Veronese M, Rizzo G, Aboagye E, Bertoldo A (2014) Parametric imaging of 18F-fluoro-3-deoxy-3-L-fluorothymidine PET data to investigate tumor heterogeneity Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014 Apr 5. (Epub ahead of print)

Bentourkia M (2003) PET kinetic modeling of 11C-acetate from projections. Comput Med Imaging Graph 27(5):373–379

Marshall RC, Powers-Risius P, Reutter BW, O’Neil JP, La Belle M, Huesman RH, VanBrocklin HF (2004) Kinetic analysis of 18F-fluorodihydrorotenone as a deposited myocardial flow tracer: comparison to 201Tl. J Nucl Med 45(11):1950–1959

Turkheimer FE, Sokoloff L, Bertoldo A, Lucignani G, Reivich M, Jaggi JL, Schmidt K (1998) Estimation of component and parameter distributions in spectral analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 18(11):1211–1222

Turkheimer FE, Edison P, Pavese N, Roncaroli F, Anderson AN, Hammers A, Gerhard A, Hinz R, Tai YF, Brooks DJ (2007) Reference and target region modeling of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 brain studies. J Nucl Med 48(1):158–167

Hammers A, Asselin M-C, Turkheimer FE, Hinz R, Osman S, Hotton G, Brooks DJ, Duncan JS, Koepp MJ (2007) Balancing bias, reliability, noise properties and the need for parametric maps in quantitative ligand PET: PET: [(11)C]diprenorphine test-retest data. Neuroimage 38(1):82–94

Rizzo G, Veronese M, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Bertoldo A (2013) Voxelwise quantification of [(11)C](R)-rolipram PET data: a comparison between model-based and data-driven methods. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33(7):1032–1040

Zanotti-Fregonara P, Leroy C, Roumenov D, Trichard C, Martinot JL, Bottlaender M (2013) Kinetic analysis of [11C]befloxatone in the human brain, a selective radioligand to image monoamine oxidase A. EJNMMI Res 3(1):78

Bertoldo A, Vicini P, Sambuceti G, Lammertsma AA, Parodi O, Cobelli C (1998) Evaluation of compartmental and spectral analysis models of [18F] FDG kinetics for heart and brain studies with PET. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 45(12):1429–1448

Bertoldo A, Peltoniemi P, Oikonen V, Knuuti J, Nuutila P, Cobelli C (2001) Kinetic modeling of [18F] FDG in skeletal muscle by PET: a four-compartment five-rate-constant model. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281(3):E524–E536

Pencek RR, Bertoldo A, Price J, Kelley C, Cobelli C, Kelley DE (2006) Dose-responsive insulin regulation of glucose transport in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290(6):E1124–E1130

Kenny LM, Vigushin DM, Al-Nahhas A, Osman S, Luthra SK, Shousha S, Coombes RC, Aboagye EO (2005) Quantification of cellular proliferation in tumor and normal tissues of patients with breast cancer by [18F]fluorothymidine-positron emission tomography imaging: evaluation of analytical methods. Cancer Res 65(21):10104–10112

Wells P, Aboagye E, Gunn RN, Osman S, Boddy AV, Taylor GA, Rafi I, Hughes AN, Calvert AH, Price PM, Newell DR (2003) 2-[11C]thymidine positron emission tomography as an indicator of thymidylate synthase inhibition in patients treated with AG337. J Natl Cancer Inst 95(9):675–682

Gunn RN, Gunn SR, Turkheimer FE, Aston JA, Cunningham VJ (2002) Positron emission tomography compartmental models: a basis pursuit strategy for kinetic modeling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22(12):1425–1439

Turkheimer FE, Hinz R, Gunn RN, Aston JA, Gunn SR, Cunningham VJ (2003) Rank-shaping regularization of exponential spectral analysis for application to functional parametric mapping. Phys Med Biol 48(23):3819–3841

Veronese M, Bertoldo A, Bishu S, Unterman A, Tomasi G, Smith CB, Schmidt KC (2010) A spectral analysis approach for determination of regional rates of cerebral protein synthesis with the L-[1-(11)C]leucine PET method. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30:1460–1476

Veronese M, Schmidt KC, Smith CB, Bertoldo A (2012) Use of spectral analysis with iterative filter for voxelwise determination of regional rates of cerebral protein synthesis with L-[1−11C]leucine PET. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32(6):1073–1085

Veronese M, Rizzo G, Turkheimer FE, Bertoldo A (2013) SAKE: a new quantification tool for positron emission tomography studies. Comput Methods Progr Biomed 111(1):199–213

Meyer PT, Bhagwagar Z, Cowen PJ, Cunningham VJ, Grasby PM, Hinz R (2010) Simplified quantification of 5-HT2A receptors in the human brain with [11C]MDL 100,907 PET and non-invasive kinetic analyses. Neuroimage 50:984–993

Cobelli C, Foster D, Toffolo GM (2001) Tracer kinetics in biomedical research: from data to model. Kluwer Academic/Plenum, London

Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Sakurada O, Shinohara M (1977) The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem 28:897–916

Kety SS (1951) The theory and applications of the exchange of inert gas at the lungs and tissues. Pharmacol Rev 3:1–41

Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Kilbourn MR, Wooten GF, Welch MJ (1984) A quantitative model for the in vivo assessment of drug binding sites with positron emission tomography. Ann Neurol 15(3):217–227

Mazoyer BM, Huesman RH, Budinger TF, Knittel BL (1986) Dynamic PET data analysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr 10:645–653

van der Weerdt AP, Klein LJ, Boellaard R, Visser CA, Visser FC, Lammertsma AA (2001) Image-derived input functions for determination of MRGlu in cardiac (18)F-FDG PET scans. J Nucl Med 42(11):1622–1629

Ludemann L, Sreenivasa G, Michel R, Rosner C, Plotkin M, Felix R, Wust P, Amthauer H (2006) Corrections of arterial input function for dynamic H215O PET to assess perfusion of pelvic tumours: arterial blood sampling versus image extraction. Phys Med Biol 51(11):2883–2900

Zanotti-Fregonara P, Liow JS, Fujita M, Dusch E, Zoghbi SS, Luong E, Boellaard R, Pike VW, Comtat C, Innis RB (2011) Image-derived input function for human brain using high resolution PET imaging with [C](R)-rolipram and [C]PBR28. PLoS ONE 6(2):e17056

Vriens D, de Geus-Oei LF, Oyen WJ, Visser EP (2009) A curve-fitting approach to estimate the arterial plasma input function for the assessment of glucose metabolic rate and response to treatment. J Nucl Med 50(12):1933–1939

Zanotti-Fregonara P, Hines CS, Zoghbi SS, Liow JS, Zhang Y, Pike VW, Drevets WC, Mallinger AG, Zarate CA Jr, Fujita M, Innis RB (2012) Population-based input function and image-derived input function for [11C](R)-rolipram PET imaging: methodology, validation and application to the study of major depressive disorder. Neuroimage 63(3):1532–1541

Lammertsma AA, Hume SP (1996) Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage 4(3):153–158

Gunn RN, Lammertsma AA, Hume SP, Cunningham VJ (1997) Parametric imaging of ligand-receptor binding in PET using a simplified reference region model. Neuroimage 6(4):279–287

Hong YT, Fryer TD (2010) Kinetic modelling using basis functions derived from two-tissue compartmental models with a plasma input function: general principle and application to [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Neuroimage 51:164–172

Rizzo G, Turkheimer FE, Bertoldo A (2013) Multi-scale hierarchical approach for parametric mapping: assessment on multi-compartmental models. Neuroimage 67:344–353

Tomasi G, Bertoldo A, Cobelli C (2009) PET parametric imaging improved by global-two-stage method. Ann Biomed Eng 37:419–427

Rizzo G, Turkheimer FE, Keihaninejad S, Bose SK, Hammers A, Bertoldo A (2012) Multi-Scale hierarchical generation of PET parametric maps: application and testing on a [11C]DPN study. Neuroimage 59(3):2485–2493

Kotasidis FA, Matthews JC, Reader AJ, Angelis GI, Price PM, Zaidi H (2012) Direct parametric reconstruction for dynamic [18F]-FDG PET/CT imaging in the body. In: Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC), 2012 IEEE, 27 Oct 2012–3 Nov 2012, pp 3383–3386

Kotasidis FA, Matthews JC, Reader AJ, Angelis GI, Zaidi H (2012) Application of adaptive kinetic modeling for bias propagation reduction in direct 4D image reconstruction. In: Nuclear science symposium and medical imaging conference (NSS/MIC), 2012 IEEE, 27 Oct 2012–3 Nov 2012, pp 3688–3694

Erlandsson K, Buvat I, Pretorius PH, Thomas BA, Hutton BF (2012) A review of partial volume correction techniques for emission tomography and their applications in neurology, cardiology and oncology. Phys Med Biol 57(21):R119–R159

Bencherif B, Stumpf MJ, Links JM, Frost JJ (2004) Application of MRI-based partial-volume correction to the analysis of PET images of mu-opioid receptors using statistical parametric mapping. J Nucl Med 45(3):402–408

Catana C, Guimaraes AR, Rosen BR (2013) PET and MR imaging: the odd couple or a match made in heaven? J Nucl Med 54(5):815–824

Rizzo G, Veronese M, Heckemann RA, Selvaraj S, Howes OD, Hammers A, Turkheimer FE, Bertoldo A (2014) The predictive power of brain mRNA mappings for in vivo protein density: a positron emission tomography correlation study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34:827–835

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by UK Medical Research Council (MRC) programme Grant “Quantitative methodologies for Positron Emission Tomography”, No. G1100809/1.

Conflict of interest

All the three authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Color figures online at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40336-014-0067-x.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bertoldo, A., Rizzo, G. & Veronese, M. Deriving physiological information from PET images: from SUV to compartmental modelling. Clin Transl Imaging 2, 239–251 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40336-014-0067-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40336-014-0067-x