Abstract

Clinical observations and medical reports indicate that psoriasis has a tremendous impact on patients’ lives, lowering their quality in many important areas. However, the vast majority of research deals only with health-related issues. This study aimed to compare the general quality of life of psoriasis patients and healthy volunteers by examining psychological variables thought to modify the quality of life. 42 patients with psoriasis and 42 healthy volunteers matched for gender, age and education level were tested. Flanagan Quality of Life Scale was used to evaluate general quality of life. Basic hope level was assessed with Basic Hope Inventory. Trait hope was estimated using Trait Hope Scale. Psoriasis Area Severity Index was used to assess the severity of the disease. Psoriasis patients have a significantly lower overall quality of life (p = 0.05), modified by Physical and Material Well-being (p = 0.01), Personal Development and Fulfillment (p = 0.03), and Recreation (p = 0.04). They also have lower levels of trait hope (p = 0.04) and its agency component (p = 0.01). There were moderate, negative significant correlations with basic hope and such components of quality of life as Physical and Material Well-being (p = 0.03, r = − 0.34) and Relations with other People (p = 0.02, r = − 0.35). These results support the hypothesis of a reduced general quality of life and trait hope in psoriatics. Thus, psychological help for people suffering from dermatological disorders might be as important as medical intervention. Basic hope can be treated as a resource in coping with these disorders and trait hope as a resource conducive to well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, non-infectious inflammatory skin disease of genetic basis, characterized by excessive proliferation of the epidermis. It affects approximately 2–3 % of European population (Schafer, 2006). Numerous literature reports and clinical observations suggest that this condition has significant influence on the functioning of people affected by it. The impact of psoriasis on the quality of life is comparable to the impact of other diseases, including life- threatening ones such as cancer, heart attack, diabetes, and hypertension (Rapp et al., 1999; Schafer, 2006). Therefore, van de Kerkhof described it as a ‘life-ruining disease’ because, although it does not lead directly to death, it makes life unbearable (van de Kerkhof, 2004).

Persons suffering from psoriasis experience difficulties in the physical (e.g., desquamation, pain, itching), psychological and social domains, leading to disturbances of normal, daily routines like bathing, dressing, sleep, and work. Patients also feel embarrassed and ashamed because of the presence of skin lesions. They lack confidence, experience anxiety or low mood, and sometimes have suicidal thoughts (Gupta & Gupta, 1998; Russo et al. 2004; Li and Armstrong 2012). Often persons suffering from psoriasis also experience feelings of guilt and hopelessness. They worry about the anticipated reaction of their families and colleagues to their illness, feel ashamed and angry, and have distorted self images (Choi & Koo, 2003; Vladut & Kallay, 2010). Many patients experience social rejection and are often asked to leave public places (e.g. a swimming pool) (Choi & Koo, 2003; Schmid-Ott et al., 2007). Therefore, they often decide to limit or abandon altogether their social activities in order to avoid stubborn and/or disgusted glances.

Psoriasis also impairs functioning in intimate relationships. In the study of Gupta and Gupta (1997) 40.8 % of patients with psoriasis admitted the disease affected their sexual life. Sixty percent of them felt that the appearance of the skin was directly responsible for reduced sexual activity. Physical symptoms such as joint pain, desquamation, itching also adversely affect sexual life (Gupta & Gupta, 1997). Professional activity is closely connected with social functioning of individuals. Unfortunately, due to physical symptoms alone, repeated hospitalizations and, finally, the rejection at the workplace, patients lose their sources of income. That is how the ‘life-ruining disease’ ruins also the material sphere of life (Vladut & Kallay, 2010).

Subjective-well being is frequently used to assess how individuals cope in different (including difficult) situations. It is believed to derive from the conscious experience of an individual and is expressed in the form of cognitive satisfaction. In order to determine the level of well-being experienced by an individual, one needs to refer to what s/he thinks about their life in the context of the adopted life standards (Diener & Suh, 1997).

Quality of life (QoL) is an important source of information about the functioning of patients, an indicator of how they experience and evaluate their own lives, and a valuable addition to clinical data. Current professional literature devotes much attention to the QoL of persons with psoriasis but the vast majority of research deals only with health-related quality of life (HRQOL). In addition, there is no comparative analysis between groups of patients and healthy controls. HRQOL is a narrower concept than the general quality of life, because it is focusing on the effects of illness and treatment on the sense of the patient’s well-being (Bączyk et al. 2011; Dziurowicz-Kozłowska, 2002). Nevertheless, ill-health should not be necessarily equate with a low QoL- some person are able to adapt to the disease and to achieve their goals. Hence, this study aimed to determine and compare the overall quality of life of psoriatic patients and healthy people.

Internal factors that motivate a person to act constructively and encourage self-realization play an important role in the subjective assessment of the quality of life. Therefore, this study also examined selected psychological variables, potentially modifying the quality of life, which could be treated as a resource when coping with the disease. These factors are basic hope and trait hope. The former is a concept introduced by Erik Erikson (2002) describes a belief in two basic features of the world: its higher order and benevolence. Basic hope is formed very early in psychosocial development (Erikson, 2002; Cutcliffe, 2009) and reaching that state allows a person to respond adequately to new situations and those when the existing order has been disturbed (Trzebiński & Zięba 2003a, b). The latter—trait hope—is an element of hope theory developed by Snyder (Snyder, 2002). In this approach hope is viewed as a positive motivational state based on two beliefs: strong will (agency) and the ability to solve problems (pathways). In the first case people see themselves as ‘active agents’ who are able to initiate actions that lead to achievement of goals and who persevere despite obstacles. The second refers to the perception of oneself as a resourceful person, able to invent or learn more than one way of achieving the intended purpose. It is a conviction about one’s intellectual abilities and knowledge that enables to realize one’s plans. People with higher hope deal with diseases and pain better and create more strategies of coping with them (Snyder, 2002). Also, they are more likely to engage in preventive activities, such as taking care of their physical condition and, additionally, are more consequent and thorough when following their doctor’s recommendations. Hope allows to set new goals when the old ones are no longer feasible because of the disease, and also to come up with alternative ways of achieving them, when the illness hinder their chances of reaching them through traditional means (Shorey et al., 2002).

Methods

Subjects

The study included 42 patients from the Clinic of Dermatology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, with a confirmed diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris, and 42 healthy controls. The mean duration of the disease was 16.36 years (SD = 14.21). Among the 42 persons with psoriasis (21 men and 21 women), with an average age of 42 years (min 20, max 73), the most common level of education was secondary, and the least common was higher education (47.6 % and 23.8 % respectively). The remaining 28.6 % of the respondents had vocational education. The main criterion for inclusion was health status: only people suffering exclusively from psoriasis vulgaris (excluding patients with a history of other diseases) were tested. In order to obtain an adequate control group, purposive sampling was used which resulted in the inclusion of healthy participants that were matched to psoriatic patients by gender, age (+/− 5 years; an average age of 41 years, min 19, max 69), and education. Prior to testing, all participants gave their informed consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Projects from the Institute of Psychology, at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. The surveys were conducted from October 2010 to April 2011.

Quality of Life

Quality of life—according to Flanagan (Flanagan, 1978; Brzezińska et al., 2001) is a subjective feeling of satisfying needs that are important to a given individual. These needs have been divided into five categories of ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ (WB), ‘Relations with other People’ (RP), ‘Social, Community, and Civic Activities’ (SA), ‘Personal Development and Fulfillment’ (PD), ‘Recreation’ (RE). Flanagan Quality of Life Scale (QoLS) consists of two questionnaires: ‘Importance of needs’ and ‘Needs met’, each containing 15 items (list of 15 needs), and a 7-point scale. Originally, a 5-point scale was used (Flanagan, 1978) but in our study an extensive scale was used to get a more subtle variation in response. At first, participants were asked to determine the importance of the needs, then the degree of needs met. The difference between importance and meeting of needs is an indicator of quality of life. Overall quality of life and quality of life in distinguished areas were calculated. The smaller the difference between the importance of needs and needs met (the result closer to zero) the higher the quality of life. The results are within the following ranges: overall quality of life: 0–6, WB: 0–12, RP: 0–24, SA: 0–12, PD: 0–30, RE: 0–12. Test reliability (measured with Cronbach’s alpha) is good and ranges from 0.809 for the “Importance of needs” scale to 0.835 for the ‘Needs met’ scale.

Assessment of the Basic Hope Level

Basic Hope Inventory (Trzebiński & Zięba, 2003a, b) consists of 12 statements, three of which are buffer items. Subjects are asked to determine to what extent they agreed with the statement. Respondents indicate their answers on a 5-point scale. The result, which is an indicator of the general level of basic hope, was a sum of the points obtained by the respondent with 9 statements. The results ranged from 9 to 45 points. The higher the score the higher the level of basic hope. Reliability of the questionnaire (measured with Cronbach’s alpha) is 0.537 and is relatively low.

Assessment of the Trait Hope Level

The Trait Hope Scale (Łaguna et al., 2005) consists of 12 statements - 4 relate to the agency subscale, 4 to pathway subscale, and 4 of them are buffer positions. Subjects are asked to determine the extent to which the statement describes them, taking into account different situations occurring at different times. Respondents indicate their responses on an 8-point scale. The level of trait hope was calculated by adding up the points obtained by a respondent in 8 statements. It varies between 8 and 64 points. The result for the individual components of trait hope was calculated by adding up the points obtained by test-specific statements attributed to subscales (from 4 to 32 points). The higher the score the higher the level of the factor tested. Reliability of the questionnaire (measured with Cronbach’s alpha) is satisfactory and is 0.834.

Assessing Severity of Psoriasis

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) is an observational scale, on which severity of three typical symptoms of psoriasis skin (desquamation, erythema and induration) is assessed. The results are documented on a 5-point scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (very severe). Severity of skin lesions on the head, trunk, arms and legs is assessed separately. Additionally, percentage of the body surface area occupied by lesions is estimated for each of these body parts. The results range from 0 to 72 points. The higher the score the greater clinical severity of the lesions (Schmitt & Wozel, 2005). To diminish subjectivity of this scale, PASI was always evaluated by the same dermatologist.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill, USA). The normality of data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to assess the significance of differences between the groups. r-Pearson and r-Spearman correlation size measure were used to determine the strength of the statistical relationship between the variables.

Results

In the group of persons with psoriasis, the average level of the overall quality of life was 1.16 (SD = 0.69). In the specific components the results were: ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ 3.21 (SD = 2.20), ‘Relations with other People’ 4.43 (SD = 4.16), ‘Social, Community, and Civic Activities’ 1.91 (SD = 1.62), ‘Personal Development and Fulfillment’ 4.98 (SD = 3.95), ‘Recreation’ 2.83 (SD = 2.59). In the control group the mean overall quality of life was 0.88 (SD = 0.63), and in the specific components the results were: ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ 2.12 (SD = 2.11), ‘Relations with other People’ 3.79 (SD = 3.44), ‘Social, Community, and Civic Activities’ 1.93 (SD = 2.27), ‘Personal Development and Fulfillment’ 3.33 (SD = 3.55), ‘Recreation’ 1.95 (SD = 2.40).

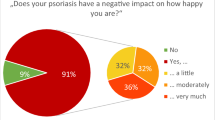

As shown in Fig. 1, persons suffering from psoriasis have a significantly lower quality of life in some of the specific areas: ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ (p = 0.01), ‘Personal Development and Fulfillment’ (p = 0.03), ‘Recreation’ (p = 0.04).

In the group of psoriatic patients, the average value of trait hope was 46.17 (SD = 7.05). The component results were: pathways 24.14 (SD = 3.02), agency 22.02 (SD = 4.69), and basic hope 28.86 (SD = 5.33). In the control group the average value of trait hope was 49.21 (SD = 6.56), pathways 25.81 (SD = 3.06), agency 23.21 (SD = 3.97), and basic hope 30.45 (SD = 3.42).

As shown in Fig. 2, persons with psoriasis have lower levels of trait hope (p = 0.04) and its pathways component (p = 0.01). No statistically significant difference was found between the group of patients and healthy controls regarding the level of basic hope (p = 0.106) and agency component of trait hope (p = 0.149).

This study indicate that gender does not differentiate the quality of life in people suffering from psoriasis. There are however significant differences in the level of trait hope (p = 0.02) and its components: agency (p = 0.04), pathways (p = 0.01) and in the quality of life in the area of ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ (p = 0.01) between ill and healthy males. Sick men have a lower quality of life in the area of ‘Physical and Material Well-being’, and lower levels of trait hope, agency and pathways.

No statistically significant difference was found in overall quality of life and in its specific areas according to the education level, both in patients and control group. On the other hand, Kruskal-Wallis test demonstrated that among examined persons with psoriasis, young adults (20–34 year of age) experienced more difficulties in the area of ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ (p = 0.027) than middle-aged adults (35–54 years of age). No differences were detected in the control group.

For 42 patients the average PASI score was 20.26 (SD = 14.94). PASI was correlated only with one of the examined psychological factors - the dimension of the quality of life scale known as ‘Social, Community, and Civic Activities’ (p > 0.01, r = 0.45, r 2 = 0.20). Once again it is worth noting that due to the method chosen for calculating the quality of life (the higher the score, the lower the quality of life), positive correlations are interpreted as indicators of a negative connection between the quality of life and a correlating factor.

No statistically significant association was found between the level of basic hope and quality of life in the study group (p = 0.09). However, there were moderate, negative significant correlations with basic hope and components of quality of life: ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ (p = 0.03, r = − 0.34, r 2 = 0.12) and ‘Relations with other People’ (p = 0.02, r = − 0.35, r 2 = 0.12). What is interesting, no correlations were found in the control group.

Correlation analysis showed no statistically significant association between the level of trait hope and the quality of life and its areas in the study group. Also, the subscale of trait hope did not correlate with the quality of life and its components. Interestingly, in the control group a statistically significant correlation between the pathways and quality of life (p = 0.05, r = −0.31, r 2 = 0.10) and quality of life in the area of ‘Recreation’ (p = 0.05, r = −0.310, r 2 = 0.10) was found.

Discussion

The present study blends into the mainstream of scientific research on people suffering from psoriasis to evaluate the quality of life, functioning areas in which patients face particular difficulties and, what is especially important, to determine factors modifying the quality of life. In most studies the HRQOL questionnaires are used, measuring health-related quality of life. This is a narrower concept than the general quality of life because it focuses particularly on deficits in functioning, while general quality of life refers to human potential, which allows him to achieve the important aspirations (Dziurowicz-Kozłowska, 2002). The use of the Flanagan QoLS in this study has enabled us to compare of the overall quality of life of psoriatic patients and healthy controls. This would be impossible or difficult using other tools, particularly those designed to measure HRQOL in dermatological diseases.

The analyses of the collected data allow us to unequivocally conclude that people suffering from psoriasis have a lower quality of life than healthy individuals in some of the specific areas. This conclusion is consistent with clinical observations. Psoriasis significantly impairs the functioning of the affected people in many spheres of life. Our results indicate that the reduction of the quality of life relates to the following particular areas: ‘Physical and Material Well-being’, ‘Personal Development and Fulfillment’, ‘Recreation’. Taking into account that health and personal safety are elements of the Flanagan’s ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ component, smaller needs met in this particular sphere of functioning seem to be justified. This is consistent with the reports stating that psoriasis is a physical problem (skin lesions, pain, pruritus, necessity to apply ointments and use medication), but also causes the feelings of anxiety, fear, shame or guilt (Gupta & Gupta, 1998; Choi & Koo, 2003; Russo et al. 2004; Vladut & Kallay, 2010). Experiencing such feelings is the opposite of “enjoying freedom from sickness”, which is a component of quality of life in the area of ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ according to Flanagan (Flanagan, 1978).

The definition of the component of ‘Personal Development and Fulfillment’, as well as ‘Recreation’ (which include categories such as: intellectual development, personal understanding and planning, professional activity, creativity and personal expression, socializing, passive and observational recreational activities, active and participatory recreational activities) further suggests that our results are consistent with literature data. As mentioned in the introduction, numerous publications report impeded social functioning of people suffering from psoriasis, what results in avoidance of public places, including those where you can relax passively and actively (beach, swimming pool, gym) (Choi & Koo, 2003; Schmid-Ott et al., 2007). Moreover, often due to absenteeism in the workplace or explicitly formulated rejection patients lose their source of income and satisfaction, feel ill at ease and lack conditions for creative self-expression.

Some works in the field of quality of life in somatic patients used the Flanagan Quality of Life Scale modified by Burckhardt. It is a questionnaire examining satisfaction in 16 areas (one position—independence—was added) (Burckhardt & Anderson, 2003). Due to the different design of the questionnaire (the validation of needs importance has been omitted), these results cannot be compared directly. In our opinion, however, assessing the importance of the needs is essential. Brickman has already demonstrated (cf. Brzezińska et al., 2001) that it is not possible to draw conclusions about the quality of life assuming that there are universal needs, equally important to everyone. Flanagan (Flanagan, 1978) has also argued that the ideal approach to measuring the quality of life has to include subjective assessment of the validity of each area given by the respondent.

Our study clearly shows that healthy people and persons with psoriasis do not differ significantly in the level of basic hope. Yet, differences in the level of trait hope and its component pathways were found between the groups. Presumably, being affected by psoriasis cannot influence the beliefs about the world (basic hope) formed in the early childhood. However, long and usually futile struggle with psoriasis can significantly reduce the level of trait hope and its pathway traits, which are formed both during childhood and later in life.

Our results also indicate that there is no connection between the PASI score and the overall quality of life. These results are consistent with studies of Wahl et al. (1998), conducted using a modified Flanagan QoLS, which also showed no connection between overall quality of life and PASI score. However, there are different reports indicating the existence of such correlations (Vardy et al., 2002; Reich & Griffiths, 2008). It should be mentioned, though, that these results are obtained using other questionnaires, usually measuring HRQOL. It should also be noted that the quality of life is a subjective indicator of how people evaluate their life. Therefore, there are situations in which clinical evaluations do not go hand in hand with the self-reports made by patients.

We found a relationship between PASI and the quality of life in the area of ‘Social, Community and Civic Activities’ such as the greater severity of the disease, the fewer satisfied needs in this area (and vice versa). It can be assumed that, with considerable skin lesions or joint pain, people are far more focused on themselves, following mainly doctor’s recommendations and fighting with the illness, than on working to achieve the common good. Moreover, severe symptoms may foster the feelings of shame and fear of the reaction of the environment, which causes withdrawal from social life.

Our findings allow us to conclude that the higher the level of basic hope, the higher the quality of life in the areas of ‘Physical and Material Well-being’ and ‘Relations with other People’, in the experimental group. This correlation has not been found in healthy controls. It is therefore possible that basic hope is activated in the situation of disease and serves as a defense mechanism with adaptive function. In the situation of struggling with psoriasis the world may seem an unfriendly place, not allowing the patients to satisfy many of their essential needs and not subject to change. Perhaps patients begin to reinterpret the surrounding reality, finding there harmony, order and meaning. Basic hope may be treated as a resource in the difficult experience of coping with the disease. Similar findings have been reported earlier in the works of Chmielewska-Hampel and Wawrzyniak (2009), who noted the regulatory role of basic hope against fear of people receiving a prison sentence.

The current study also indicates that there is no connection between trait hope (and its agency component) and the overall quality of life and its components in the experimental and the control groups. The connection between trait hope and its two components and the overall sense of quality of life and its dimensions referred to as ‘Physical and Material Well-being’, ‘Relations with other People’, ‘Personal Development and Fulfillment’ has been demonstrated among all individuals. This indicates the existence of general psychological mechanisms according to which trait hope is a resource conducive to well-being. Such a conclusion is consistent with earlier literature reports. For example, Snyder (Snyder, 2002) indicates that high level of hope is associated with greater social competence, feeling more social support, less loneliness, higher sense of satisfaction in life, greater self-esteem, better coping with physical discomfort such as pain and improved learning achievements.

The results of our study are also consistent with the works of Gupta and Gupta (1995) or Fortune et al. (1997), who showed that men and women with psoriasis did not differ in their quality of life. Nevertheless, there are studies in which such differences were found (Steuden & Janowski, 2001). Men suffering from psoriasis have lower quality of life in the area of ‘Physical and Material Well-being’, and lower levels of trait hope and its components than their healthy counterparts. It can be assumed that a long struggle with the disease affects perception of oneself as a person able to reach certain goals regardless of difficulties and/or to find alternative solutions. Interestingly enough, such correspondence was not found among the women. Perhaps in the case of women the state of health influences the perceived subjective well-being and self-beliefs less than in men. It should also be remembered that the Flanagan QoLS used in our study measures other aspects of the quality of life than the HRQoL scales used in the cited works.

Based on the results basic hope can be seen as resources in coping with psoriasis. Although basic hope is formed early during development, it is possible to change its level as a result of life experience. The change is fostered by experiences disturbing the existing order. Basic hope may also increase as a result of encountering people with an attitude of confidence in benevolence and higher order of the world (Trzebiński & Zięba 2003a, b). Our results also indicate that trait hope is a resource conducive to well-being. Therefore, it is beneficial to work with patients on their perception of themselves as people who can initiate action, who are persistent in achieving their goals and resourceful, especially since struggle with the disease is likely to adversely affect those beliefs. It is also important to emphasize that objective clinical assessment of the disease severity often does not coincide with the assessment of the quality of life of the patient. Especially in this context, psychological help for people suffering from dermatological disorders is of great importance.

References

Bączyk, G., Talarska, D., Zawirska, A., Bryl, A., & Adamski, Z. (2011). Functioning and quality of life of patients with leg ulcers treated at dermatology wards. Postepy Dermatologii I Alergologii, 28(3), 197–202.

Brzezińska, A., Stolarska, M., & Zielińska, J. (2001). Quality of life in adulthood. In K. Appelt & J. Wojciechowska (Eds.), The tasks and social roles in adulthood (pp. 103–126). Poznań: Wydawnictwo Fundacji Humaniora.

Burckhardt, C. S., & Anderson, K. L. (2003). The Quality of Life Scale (QOLS): reliability, validity, and utilization. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 23(1), 60.

Chmielewska-Hampel, A., & Wawrzyniak, M. (2009). Depression, anxiety and basic hope among prisoners. Psychologia jakości życia, 8(1), 45–58.

Choi, J., & Koo, J. Y. (2003). Quality of life issues in psoriasis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 49(2 Suppl), S57–S61.

Cutcliffe, J. R. (2009). Hope: the eternal paradigm for psychiatric/mental health nursing. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(9), 843–847.

Diener, D., & Suh, E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40(1), 189–216.

Dziurowicz-Kozłowska, A. (2002). Around the definition of the quality of life. Psychologia jakości życia, 1(2), 77–79.

Erikson, E. (2002). The life cycle completed. Poznań: Dom Wydawniczy Rebis.

Flanagan, J. C. (1978). A research approach to improving our quality of life. American Psychologist, 33(2), 138–147.

Fortune, D. G., Main, C. J., O’Sullivan, T. M., & Griffiths, C. E. (1997). Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: the contribution of clinical variables and psoriasis-specific stress. British Journal of Dermatology, 137(5), 755–760.

Gupta, M. A., & Gupta, A. K. (1995). Age and gender differences in the impact of psoriasis on quality of life. International Journal of Dermatology, 34(10), 700–703.

Gupta, M. A., & Gupta, A. K. (1997). Psoriasis and sex: a study of moderately to severely affected patients. International Journal of Dermatology, 36(4), 259–262.

Gupta, M. A., & Gupta, A. K. (1998). Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology, 139(5), 846–850.

Li, K., & Armstrong, A. W. (2012). A review of health outcomes in patients with psoriasis. Dermatologic Clinics, 30(1), 61–72.

Łaguna, M., Trzebiński, J., & Zięba, M. (2005). Trait hope scale. Manual. Warsaw: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP.

Rapp, S. R., Feldman, S. R., Exum, M. L., Fleischer, A. B., Jr., & Reboussin, D. M. (1999). Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 41(3 Pt 1), 401–407.

Reich, K., & Griffiths, C. E. (2008). The relationship between quality of life and skin clearance in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: lessons learnt from clinical trials with infliximab. Archives of Dermatological Research, 300(10), 537–544.

Russo, P. A., Ilchef, R., & Cooper, A. J. (2004). Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis: a review. Australasian Journal of Dermatology, 45(3), 155–159.

Schafer, T. (2006). Epidemiology of psoriasis. Review and the German perspective. Dermatology, 212(4), 327–237.

Schmid-Ott, G., Schallmayer, S., & Calliess, I. T. (2007). Quality of life in patients with psoriasis and psoriasis arthritis with a special focus on stigmatization experience. Clinics in Dermatology, 25(6), 547–554.

Schmitt, J., & Wozel, G. (2005). The psoriasis area and severity index is the adequate criterion to define severity in chronic plaque -type psoriasis. Dermatology, 210(3), 194–199.

Shorey, H. S., Snyder, C. R., Rand, K. L., Hockemeyer, J. R., & Feldman, D. B. (2002). Somewhere over the rainbow: hope theory weathers its first decade. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 322–331.

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249–275.

Steuden, S., & Janowski, K. (2001). The application of the quality-of-life questionnaire SKINDEX in patients with psoriasis. Przegla̧d Dermatologiczny, 88(1), 41–48.

Trzebiński, J., & Zięba, M. (2003a). Hope, loss and personal growth. Psychologia Jakości Życia, 2(1), 5–33.

Trzebiński, J., & Zięba, M. (2003b). Basic hope inventory – BHI-12. Manual. Warsaw: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP.

van de Kerkhof, P. C. (2004). The impact of a two -compound product containing calcipotriol and betamethasone dipropionate (Daivobet/Dovobet) on the quality of life in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Dermatology, 151(3), 663–668.

Vardy, D., Besser, A., Amir, M., Gesthalter, B., Biton, A., & Buskila, D. (2002). Experiences of stigmatization play a role in mediating the impact of disease severity on quality of life in psoriasis patients. British Journal of Dermatology, 147(4), 736–742.

Vladut, C. I., & Kallay, E. (2010). Psychosocial implications of psoriasis-theoretical review. Cognition, Brain, Behavior An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14(1), 23–35.

Wahl, A., Burckhardt, C., Wiklund, I., & Hanestad, B. R. (1998). The Norwegian version of the Quality of Life Scale (QOLS-N). A validation and reliability study in patients suffering from psoriasis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 12(4), 215–222.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Szramka-Pawlak, B., Hornowska, E., Walkowiak, H. et al. Hope as a Psychological Factor Affecting Quality of Life in Patients With Psoriasis. Applied Research Quality Life 9, 273–283 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-013-9222-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-013-9222-1