Abstract

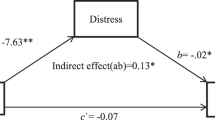

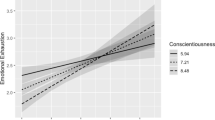

Pregnancy represents a critical time during which women are increasingly susceptible to challenges that can shape maternal health postpartum. Given the increasing number of women who are working through the duration of their pregnancies, in this study, we examine the extent to which both maternal psychological and physical health are influenced by social support received at work during pregnancy. Specifically, we examine 118 pregnant employees’ perceptions of coworker support, supervisor support, and stress over the course of 15 working days. We then link prenatal stress levels with postpartum maternal health outcomes following women’s return to work. At the within-person level, coworker support predicted next-day decreases in stress during pregnancy; however, stress did not predict next-day change in coworker support. There was no relationship between supervisor support and next-day change in stress during pregnancy or vice versa. At the between-person level, an interactive effect between coworker support and supervisor support emerged in predicting prenatal stress, such that women who benefitted from supportive coworkers and supportive supervisors during pregnancy reported the lowest levels of prenatal stress which were, in turn, associated with lower incidence of postpartum depression and quicker recovery times from birth-related injuries. Significant indirect effects suggested that when perceptions of supervisor support were higher (but not lower), coworker support during pregnancy predicted lower incidence of postpartum depression and quicker recovery times through reduced prenatal stress. Taken together, our findings provide novel insight into how specific aspects of the workplace environment may interact to shape maternal psychological and physical health during pregnancy and postpartum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Extant evidence suggests typical healing times for each type of injury are comparable (Wick, 2018). According to the Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy, women who are recovering from a cesarean section should avoid driving for 1-2 weeks, are usually able to resume normal activities at home within 3-4 weeks, and are recommended to avoid sex for 4-6 weeks post-surgery. Similarly, women who received stitches due to a perineal tear during delivery typically experience discomfort for 1-2 weeks post-delivery with the tissue taking about 6 weeks to regain its natural strength.

We were unable to consider both sources of support and their relations with stress simultaneously in the same within-person (BLCS) model. This is because such an approach requires the estimation of a number of paths so high that convergence cannot be achieved. Specifically, autoregressive effects are modeled by estimating the paths between support1, support2, support3 all the way up to support15. The same paths are then estimated for stress1, stress 2, stress3, all the way up to stress15. Next, latent change scores (i.e., difference scores) are modeled at each point in time (excluding time 1) for each variable as measured by the change in that variable relative to the previous time point beyond autoregressive effects. For example, the difference between support at time 1 and support at time 2 represents the latent change score for support at time 2. The proportional change parameters are then estimated by regressing the latent change score for support at time 2 onto the true score for support at time 1, regressing the latent change score for support at time 3 onto the true score for support at time 2, and so on. All of these paths are then estimated for the other variable of interest, stress. Finally, the coupling parameters are estimated by specifying a path from the true score for support at time 1 to the latent change score for stress at time 2, and vice versa by specifying a path from the true score for stress at time 1 to the latent change score for support at time 2, and so on up to time 15. Thus, adding a third variable (i.e., the other source of support) and all of the required associated parameters (autoregressive, proportional change, and coupling parameters) overwhelms the model and precludes convergence.

References

Aiken & West (1991): Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2013). Weight Gain During Pregnancy. https://www.acog.org/-/media/project/acog/acogorg/clinical/files/committee-opinion/articles/2013/01/weight-gain-during-pregnancy.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2021

Andersson, L., Sundstrom-Poromaa, I., Wulff, M., Astrom, M., & Bixo, M. (2004). Neonatal outcome following maternal antenatal depression and anxiety: A population-based study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159, 872–881. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh122.

Arena, D. F., Jones, K. P., Sabat, I. E., & King, E. B. (2021). The intrapersonal experience of pregnancy at work: An exploratory study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36, 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09661-8.

Assadi, S. N. (2015). Women’s psychological stress and obstetric disorders. Journal of Midwifery & Reproductive Health, 3, 451–455. https://doi.org/10.22038/JMRH.2015.4812.

Austin, M. P. (2003). Psychosocial assessment and management of depression and anxiety in pregnancy. Key aspects of antenatal care for general practice. Australian Family Physician, 32, 119–126.

Austin, M. P., & Priest, S. R. (2004). Clinical issues in perinatal mental health: New developments in the detection and treatment of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00549.x.

Baethge, A., Vahle-Hinz, T., & Rigotti, T. (2020). Coworker support and its relationship to allostasis during a workday: A diary study on trajectories of heart rate variability during work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105, 506–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000445.

Baruch-Feldman, C., Brondolo, E., Ben-Dayan, D., & Schwartz, J. (2002). Sources of social support and burnout, job satisfaction and productivity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.7.1.84.

Beck, C. T. (2001). Predictors of postpartum depression: An update. Nursing Research, 50, 275–285.

Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2016). A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology, 69, 229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103.

Brady, J. M., Hammer, L. B., Mohr, C. D., & Bodner, T. D. (2021). Supportive supervisor training improves family relationships among employee and spouse dyads. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26, 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000264.

Brugha, T. S., Sharp, H. M., Cooper, S. A., Weisender, D. B., Britto, D., Shinkwin, R., Sheriff, T., & Kirwan, P. H. (1998). The Leicester 500 Project. Social support and the development of postnatal depressive symptoms, a prospective cohort survey. Psychological Medicine, 28, 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291797005655.

Chen, S., Westman, M., & Eden, D. (2009). Impact of enhanced resources on anticipatory stress and adjustment to new information technology: A field-experimental test of conservation of resources theory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14, 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015282.

Cohen, S., Tyrrell, D. A., & Smith, A. P. (1991). Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. New England Journal of Medicine, 325, 606–612. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199108293250903.

Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Skoner, D. P., Rabin, B. S., & Gwaltney Jr., J. M. (1997). Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. Journal of the American Medical Association, 277, 1940–1944. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540480040036.

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. Jama, 298, 1685–1687. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.14.1685.

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., Doyle, W. J., Miller, G. E., Frank, E., Rabin, B. S., & Turner, R. B. (2012). Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 5995–5999. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118355109.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Colella, A., Hebl, M., & King, E. (2017). One hundred years of discrimination research in Journal of Applied Psychology: A sobering synopsis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102, 500–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000084.

Collins, N. L., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Lobel, M., & Scrimshaw, S. C. M. (1993). Social support in pregnancy: Psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1243–1258. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.65.6.1243.

Dagher, R. K., McGovern, P. M., Alexander, B. H., Dowd, B. E., Ukestad, L. K., & McCaffrey, D. J. (2009). The psychosocial work environment and maternal postpartum depression. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-008-9014-4.

Diestel, S., & Schmidt, K. (2012). Lagged mediator effects of self-control demands on psychological strain and absenteeism. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85, 556–578. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2012.02058.x.

Drach-Zahavy, A., & Somech, A. (2008). Coping with work-family conflict: Integrating individual and organizational perspectives. In K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds.), Handbook of work-family integration: Research, theory, and best practices (pp. 267–285). Academic Press.

Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal strivings: An approach to personality and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 59, 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.5.1058.

Friedman, S. D., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2000). Work and family—allies or enemies? What happens when business professionals confront life choices. Oxford University Press.

Frone, M. R. (2000). Interpersonal conflict at work and psychological outcomes: Testing a model among young workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.246.

Gabriel, A. S., Volpone, S. D., MacGowan, R. L., Butts, M. M., & Moran, C. M. (2020). When work and family blend together: Examining the daily experiences of breastfeeding mothers at work. Academy of Management Journal, 63, 1337–1369. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.1241.

Ganster, D. C., Fusilier, M. R., & Mayes, B. T. (1986). Role of social support in the experience of stress at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.1.102.

Gao, G., & Livingston, G. (2015). Working while pregnant is much more common than it used to be. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/03/31/working-while-pregnant-is-much-more-common-than-it-used-to-be/. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Grandey, A. A., Gabriel, A. S., & King, E. B. (2020). Tackling taboo topics: A review of the Three Ms in working women’s lives. Journal of Management, 46, 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319857144.

Greenhaus, J. H., Ziegert, J. C., & Allen, T. D. (2012). When family-supportive supervision matters: Relations between multiple sources of support and work–family balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.008.

Gueutal, H. G., & Taylor, E. M. (1991). Employee pregnancy: The impact on organizations, pregnant employees and co-workers. Journal of Business and Psychology, 5, 459–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01014495.

Hackney, K. J., Daniels, S. R., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., Perrewé, P. L., Mandeville, A., & Eaton, A. A. (2021). Examining the effects of perceived pregnancy discrimination on mother and baby health. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106, 774–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000788.

Hagihara, A., Tarumi, K., & Miller, A. S. (1998). Social support at work as a buffer of work stress-strain relationship: A signal detection approach. Stress Medicine, 14, 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1700(199804)14:2<75:AID-SMI7583.0.CO;2-A.

Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2006). Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1134.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Buckley, M. R. (2004). Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management, 30, 859–879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.004.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Zellars, K., Carlson, D. C., Perrewe, P. L., & Rotondo, D. (2010). Moderating effect of work-linked couple relationships and work-family integration on the spouse instrumental support-emotional exhaustion relationship. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020521.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Wheeler, A. R., & Rossi, A. M. (2012). The costs and benefits of working with one’s spouse: A two-sample examination of spousal support, work-family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in work-linked relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 597–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.771.

Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40, 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130.

Halpert, J. A., Wilson, M. L., & Hickman, J. L. (1993). Pregnancy as a source of bias in performance appraisals. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14, 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030140704.

Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Yragui, N. L., Bodner, T. E., & Hanson, G. C. (2009). Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management, 35, 837–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308328510.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Anger, W. K., Bodner, T., & Zimmerman, K. L. (2011). Clarifying work-family intervention processes: The roles of work-family conflict and family supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020927.

Hammer, L. B., Brady, J. M., & Perry, M. L. (2020). Training supervisors to support veterans at work: Effects on supervisor attitudes and employee sleep and stress. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93, 273–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12299.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. [White paper]. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

Hebl, M. R., King, E. B., Glick, P., Singletary, S. L., & Kazama, S. (2007). Hostile and benevolent reactions toward pregnant women: Complementary interpersonal punishments and rewards that maintain traditional roles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1499–1511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1499.

Heron, J., O ' Connor, T. G., Evans, J., Golding, J., & Glover, V. (2004). The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 80, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004.

Hert, M., Correll, C. U., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M. A., Cohen, D. A., Asai, I., Detraux, J., Gautam, S., Möller, H. J., Ndetei, D. M., Newcomer, J. W., Uwakwe, R., & Leucht, S. (2011). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry, 10, 52–77.

Hobfell, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6, 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44, 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513.

Hobfoll, S. E., & Stokes, J. P. (1988). The process and mechanics of social support. In S. Duck, D. F. Hay, S. E. Hobfoll, W. Ickes, & B. M. Montgomery (Eds.), Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research and interventions (pp. 497–517). John Wiley & Sons.

Hochwarter, W. A., Witt, L. A., Treadway, D. C., & Ferris, G. R. (2006). The interaction of social skill and organizational support on job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 482–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.482.

House, J. S. (1981). Work Stress and Social Support. Addison-Wesley.

Huffman, A. H., Wastrous-Rodriguez, K. M., & King, E. B. (2008). Supporting a diverse workforce: What type of support is most meaningful for lesbian and gay employees? Human Resource Management, 47, 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20210.

Johnson, T. D. (2008). Maternity leave and employment: Patterns of first-time mothers 1961-2003. United States Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p70-113.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Johnson, R. C., & Slade, P. (2003). Obstetric complications and anxiety during pregnancy: Is there a relationship? Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 24, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674820309042796.

Jones, K. P. (2017). To tell or not to tell? Examining the role of discrimination in the pregnancy disclosure process at work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000030.

Jones, K. P., King, E. B., Gilrane, V. L., McCausland, T. C., Cortina, J. M., & Grimm, K. J. (2016). The baby bump: Managing a dynamic stigma over time. Journal of Management, 42, 1530–1556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313503012.

Katon, W. J. (2011). Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13, 7–23.

King, E. B., & Botsford, W. E. (2009). Managing pregnancy disclosures: Understanding and overcoming the challenges of expectant motherhood at work. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 314–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.003.

Kitroeff, J., & Silver-Greenberg, N. (2018). Pregnancy discrimination is rampant inside America’s biggest companies. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/06/15/business/pregnancy-discrimination.html/. Acceseed 15 Jan 2020.

Ko, J. Y., Rockhill, K. M., Tong, V. T., Morrow, B., & Farr, S. L. (2017). Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms - 27 States, 2004, 2008, and 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66, 153–158. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6606a1.

Kuijper, E. A. M., Ket, J. C. F., Caanen, M. R., & Lambalk, C. B. (2013). Reproductive hormone concentrations in pregnancy and neonates: A systematic review. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 27, 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.03.009.

Ladge, J. J., Clair, J. A., & Greenberg, D. (2012). Cross-domain identity transition during liminal periods: Constructing multiple selves as professional and mother during pregnancy. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1449–1471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0538.

Laughlin, L. (2011). Maternity leave and employment patterns: 2006–2008. Current Population Report, P70-128. U.S. Census Bureau.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer.

Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123.

Little, L. M., Smith Major, V., Hinojosa, A. S., & Nelson, D. L. (2015). Professional image maintenance: How women navigate pregnancy in the workplace. Academy of Management, 58, 8–37. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0599.

Little, L. M., Hinojosa, A. S., & Lynch, J. (2017). Make them feel: How the disclosure of pregnancy to a supervisor leads to changes in perceived supervisor support. Organization Science, 28, 618–635. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1136.

Little, L. M., Hinojosa, A. S., Paustian-Underdahl, S., & Zipay, K. P. (2018). Managing the harmful effects of unsupportive organizations during pregnancy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103, 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000285.

Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., Fu, P. P., & Mao, Y. (2013). Ethical leadership and job performance in China: The roles of work-place friendships and traditionality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86, 564–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12027.

Livingston, G. (2014). Opting out? About 10% of highly educated moms are staying home. Pew Research Center http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/05/07/opting-out-about-10-of-highly-educated-moms-are-staying-at-home. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation of Australia.

Luszczynska, A., & Cieslak, R. (2005). Protective, promotive, and buffering effects of perceived social support in managerial stress: The moderating role of personality. Anxiety, Stress and Coping: An International Journal, 18, 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800500125587.

Matthews, S. G., & Meany, M. J. (2005). Maternal adversity, vulnerability, & disease. In A. Riecher-Rossler & M. Steiner (Eds.), Perinatal stress, mood, and anxiety disorders: From bench to bedside (pp. 28–49). S Karger AG.

McArdle, J. J. (2009). Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 577–605. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612.

Ming, E. E., Adler, G. K., Kessler, R. C., Fogg, L. F., Matthews, K. A., Herd, J. A., & Rose, R. M. (2004). Cardiovascular reactivity to work stress predicts subsequent onset of hypertension: The Air Traffic Controller Health Change Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66, 459–465. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000132872.71870.6d.

Morgan, W. B., Walker, S. S., Hebl, M. R., & King, E. B. (2013). A field experiment: Reducing interpersonal discrimination toward pregnant job applicants. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1037//a0034040.

Morikawa, M., Okada, T., Ando, M., Aleksic, B., Kunimoto, S., Nakamura, Y., Kubota, C., Uno, Y., Tamaji, A., Hayakawa, N., Furumura, K., Shiino, T., Morita, T., Ishikawa, N., Ohoka, H., Usui, H., Banno, N., Murase, S., Goto, S., … & Ozaki, N. (2015). Relationship between social support during pregnancy and postpartum depressive state: A prospective cohort study. Scientific Reports, 5, 10520. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10520

Mulder, E. J. H., Robles de Medina, P. G., Huizink, A. C., Van de Bergh, B. R. H., Buitelaar, J. K., & Visser, G. H. A. (2002). Prenatal maternal stress: Effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early Human Development, 70, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-3782(02)00075-0.

Neveu, J. P. (2007). Jailed resources: Conservation of resource theory as applied to burnout among prison guards. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28, 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.393.

Olson, J. E., Shu, X. O., Ross, J. A., Pendergrass, T., & Robison, L. L. (1997). Medical record validation of maternally reported birth characteristics and pregnancy-related events: A report from the Children’s Cancer Group. American Journal of Epidemiology, 145, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009032.

Pittenger, C., & Duman, R. S. (2008). Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: A convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 88–109. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.npp.1301574.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141.

Rijnders, M., Baston, H., Schönbeck, Y., Van Der Pal, K., Prins, M., Green, J., & Buitendijk, S. (2008). Perinatal factors related to negative or positive recall of birth experience in women 3 years postpartum in the Netherlands. Birth, 35, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00223.x.

Ross, L. E., Sellers, E. M., Gilbert Evans, S. E., & Romach, M. K. (2004). Mood changes during pregnancy and the postpartum period: Development of a biopsychosocial model. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, 109, 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00296.x.

Rynes, S. L., Gerhart, B., & Parks, L. (2005). Personnel psychology: Performance evaluation and pay for performance. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 571–600. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070254.

Saunders, T. A., Lobel, M., Veloso, C., & Meyer, B. A. (2006). Prenatal maternal stress is associated with delivery analgesia and unplanned cesareans. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, 27, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820500420637.

Segerstrom, S. C., & Miller, G. E. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 601–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601.

Spector, P. E., Dwyer, D. J., & Jex, S. M. (1988). Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison of multiple data sources. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.73.1.11.

Swendsen, J. D., & Mazure, C. M. (2000). Life stress as a risk factor for postpartum depression: Current research and methodological issues. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.7.1.17.

Thompson, J. F., Roberts, C. L., Currie, M., & Ellwood, D. A. (2002). Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: Associations with parity and method of birth. Birth, 29, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536X.2002.00167.x.

Thurgood, S., Avery, D. M., & Williamson, L. (2009). Postpartum depression (PPD). American Journal of Clinical Medicine, 6, 17–22.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2013). News release: American time use survey. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/atus_06182014.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division. (2012). Fact sheet #28: The Family and Medical Leave Act. https://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/whdfs28.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

Van Dinter, M. C., & Graves, L. (2012). Managing adverse birth outcomes: Helping parents and families cope. American Family Physician, 85, 900–904.

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 314–334. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661.

Wadhwa, P. D., Sandman, C. A., Porto, M., Dunkel-Schetter, C., & Garite, T. J. (1993). The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: A prospective investigation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 169, 858–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(93)90016-C.

Waldenström, U., & Schytt, E. (2009). A longitudinal study of women’s memory of labour pain-From 2 months to 5 years after the birth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 116, 577–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02020.x.

Westman, M., & Etzion, D. (2005). The crossover of work-family conflict from one spouse to the other. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 1936–1957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02203.x.

Wick, M. J. (2018). Mayo Clinic guide to a healthy pregnancy (2nd ed.). Mayo Clinic Press.

Wisner, K. L., Sit, D. K. Y., McShea, M. C., Rizzo, D. M., Zoretich, R. A., Hughes, C. L., Eng, H. F., Luther, J. F., Wisniewski, S. R., Costantino, M. L., Confer, A. L., Moses-Kolko, E. L., Famy, C. S., & Hanusa, B. H. (2013). Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. Journal of American Medical Association Psychiatry, 70, 490–498. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X285633.

Zimmermann, B. K., Dormann, C., & Dollard, M. F. (2011). On the positive aspects of customers: Customer-initiated support and affective crossover in employee-customer dyads. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02011.x.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and developmental guidance throughout the review process. We would also like to thank Dr. Allison Gabriel for providing a friendly review of our manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM Foundation Dissertation Grant), the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP Graduate Student Scholarship), the American Psychological Foundation (Sandra Schwartz Tangri Memorial Award for Graduate Student Research), the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (Grants-In-Aid Award), and the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (Kathryn Brooks Scholarship).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. Data transparency information

Appendix. Data transparency information

The data reported in this manuscript were collected as part of a larger data collection, and findings have been published in one other manuscript (MS1). MS1 (published) focuses on event-level measures including anticipated discrimination; revealing, concealing, and signaling pregnancy; experienced discrimination, anxiety, and depression. The variables of focus in MS1 were only assessed when participants experienced a particular event of interest during the 15-day data collection and therefore only pertain to a subsample of participants. MS2 (the current manuscript) focuses on perceived coworker support, perceived supervisor support, stress, postpartum depression, and postpartum recovery time from birth-related injury. Perceived coworker support, perceived supervisor support, and stress were also collected during the 15-day data collection but pertain to the full sample of participants because they were collected on a pre-determined schedule (i.e., at the beginning of each workday). Variables 1–10 were collected during wave 1 of data collection and variables 11 and 12 (the postpartum measures) were collected approximately 2 years later during wave 2. Thus, there is some degree of overlap in the samples of MS1 and MS2 (MS1 is a subsample of MS2); however, there is no overlap in the variables of focus or the relationships examined between MS1 and MS2.

Variables in the complete dataset | Proportion of full sample of participants | Time of data collection | MS 1 (STATUS=pub) | MS 2 (STATUS=current) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Anticipated discrimination | Subsample N = 72 | Wave 1 (event-level) | X | |

2. Revealing pregnancy | Subsample N = 72 | Wave 1 (event-level) | X | |

3. Concealing pregnancy | Subsample N = 72 | Wave 1 (event-level) | X | |

4. Signaling pregnancy | Subsample N = 72 | Wave 1 (event-level) | X | |

5. Experienced discrimination | Subsample N = 72 | Wave 1 (event-level) | X | |

6. Anxiety | Subsample N = 72 | Wave 1 (event-level) | X | |

7. Depression | Subsample N = 72 | Wave 1 (event-level) | X | |

8. Perceived coworker support | Full sample N = 118 n = 1594 | Wave 1 (daily baseline) | X | |

9. Perceived supervisor support | Full sample N = 118 n = 1594 | Wave 1 (daily baseline) | X | |

10. Stress | Full sample N = 118 n = 1594 | Wave 1 (daily baseline) | X | |

11. Postpartum depression | Subsample N = 87 | Wave 2 (one-time follow-up) | X | |

12. Postpartum recovery time | Subsample N = 69 | Wave 2 (one-time follow-up) | X |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, K.P., Brady, J.M., Lindsey, A.P. et al. The Interactive Effects of Coworker and Supervisor Support on Prenatal Stress and Postpartum Health: a Time-Lagged Investigation. J Bus Psychol 37, 469–490 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-021-09756-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-021-09756-1