Abstract

More than 109 base pairs of the genome in higher eucaryotes are positioned in the interphase nucleus such that gene activation, gene repression, remote gene regulation by enhancer elements, and reading as well as adjusting epigenetic marks are possible. One important structural and functional component of chromatin organization is the zinc finger factor CTCF. Two decades of research has advanced the understanding of the fundamental role that CTCF plays in regulating such a vast expanse of DNA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The remarkable chromatin-organizing factor CTCF was discovered in 1990 (Baniahmad et al. 1990; Lobanenkov et al. 1990) and has gained increasing attention especially during the last decade (Table 1). Important results in chromatin-mediated molecular mechanisms have been catalyzed by the CTCF connection. During this time, many key aspects of chromatin structure and function in general and the key role of CTCF in particular were brought to light. Here we detail important chromatin-mediated molecular mechanisms and highlight the fundamental role played in them by CTCF. The different levels of CTCF action start with chromatin binding and nucleosomal positioning. Three-dimensional enhancer function and blocking by CTCF is the next level. How are interactions in cis or in trans mediated, and what is the role of cohesin binding in these? Furthermore, the involvement of CTCF in specific chromatin features such as imprinting, X-chromosome inactivation, and heterochromatin barrier function are discussed.

How are nucleosomes positioned, and what does it have to do with CTCF?

In eukaryotes, DNA is packaged into a protein–DNA complex termed chromatin where 147 bp of DNA is wrapped around histone octamers to form nucleosomes that are typically separated by 20–50 bp of linker DNA. For about half of the genome, the precise position of a given nucleosome relative to the genomic sequence varies between individual nuclei, i.e., the nucleosomes are not regularly positioned. However, in order for DNA-binding factors to bind, nucleosomes have to be properly positioned. Currently, a number of factors are known to play a role in determining the position of nucleosomes such as the underlying sequence of the DNA, the availability/binding of transcription factors, and subsequent recruitment of nucleosome remodeling activities (Segal and Widom 2009).

A first indication that the sequences in the vicinity of a CTCF binding site (CTS) are marked by a specific pattern of nucleosome occupancy came from the analysis of the H19 imprinting control region (ICR). In this study, the CTSs were found at linker regions between positioned nucleosomes (Kanduri et al. 2002). Recent advances in high-throughput analyses of nucleosome occupancy have now shown that CTSs are associated with precise positioning of up to 20 nucleosomes (Fu et al. 2008).

What causes this arrangement of precisely positioned nucleosomes in relationship to CTSs? Since no sequence conservation in the regions adjacent to the CTSs has been found, CTCF binding on its own was suggested to be able to move and arrange nucleosomes into evenly spaced positions (Fu et al. 2008). However, in the case of the H19 ICR, it was conclusively shown that the nucleosome positioning is a feature of the underlying sequence rather than the presence of CTCF (Kanduri et al. 2002). Moreover, there is intrinsic sequence information in a large fraction of the genome that controls nucleosome positioning despite the absence of any detectable sequence motif (Segal and Widom 2009). Thus, CTCF binding within an array of positioned nucleosomes may work through two different mechanisms. On the one hand, the evolution of large stretches of sequences capable of positioning nucleosomes may have co-evolved with the emergence of CTSs within the corresponding linker regions. On the other hand, the finding that CTCF interacts with the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler CHD8 (Ishihara et al. 2006) may suggest an active role in controlling nucleosome movement to initiate nucleosomal phasing.

How do enhancers function?

Enhancers operate by increasing the likelihood of transcriptional activation of nearby genes (Fiering et al. 2000; Li et al. 2006). The enhancer regions, which are made up of multiple cis-regulatory elements attracting trans-acting factors, can be positioned on either side of the transcriptional start site as well as at long distances from the promoter, sometimes far beyond 100 kb (Sagai et al. 2009). The CTCF-dependent chromatin insulator activity antagonizes both short- and long-range enhancer functions in a manner that, although poorly understood, in all likelihood reflects upon the mode of enhancer action.

Despite several decades of intensive research, the inner workings of enhancer functions remain enigmatic. One mechanism of enhancer function has been suggested to take place via the formation of a chromatin loop, resulting in enhancer contacts with the gene promoter (Carter et al. 2002; Ohlsson et al. 2001; Phillips and Corces 2009; Tolhuis et al. 2002). Such a formation can be achieved either by the enhancer tracking along the chromatin fiber itself, or by the direct formation of enhancer–promoter chromatin loops or combinations thereof. An alternative mechanism for enhancer-mediated transcriptional activation involves the so-called transcription factory (Faro-Trindade and Cook 2006). This transient transcription factory structure, which can be visualized by antibodies against active RNA polymerase II, appears to support simultaneous transcription of many coding genes (Sutherland and Bickmore 2009). Thus, to provide insights into how enhancers work, the question of how these transcription factories are formed will need to be addressed.

Real-time analysis has revealed that transcriptional activation is preceded by increased mobility of chromatin fibers (Chuang et al. 2006). Chromatin marks, such as histone acetylation, are associated with increased chromatin mobility and flexibility (Li et al. 2006), raising the possibility that enhancers regulate these features by tracking along the chromatin fiber to leave acetylated histones in its wake. This process has two pivotal consequences: An enhanced ability of a transcriptional unit to explore its environments may eventually lead to the recognition of a nearby transcription factory and/or to the clustering of transcription units prior to overt transcriptional activation. Such clustering was observed at the TH2-cell locus with neighboring interleukin 4, 5, and 13 genes in type-2 helper T cells (TH2 cells) being primed for transcriptional activation (Cai et al. 2006). Moreover, the formation of a transcription factory on these physically aligned regulatory elements was suggested to coordinate their expression (Cai et al. 2006). Thus, compacting genomic sequences into a small volume increases the chances of enhancer/promoter interaction. Whether formation of a transcription factory may be assisted by the interaction of CTCF molecules flanking such clusters remains to be shown.

How are enhancers blocked to prevent unscheduled promoter activation?

Chromatin insulators may have evolved in concert with the emergence of gene clusters to differentially regulate the activity of cluster members. Indeed, coexpressed genes are generally flanked by CTS elements (Xie et al. 2007). Furthermore, insulators can act over large distances, in excess of 100 kb, to shield particular promoters from enhancer functions in developmentally regulated fashions (Wallace and Felsenfeld 2007). This property requires that the insulator is located between enhancer(s) and a promoter, in order to be kept inactive. In contrast to repressors, however, chromatin insulators act in a position-dependent manner, a feature strongly suggesting that this process acts in a linear manner. In support of this notion is the evidence that CTCF binds to the insulator of the maternally inherited H19 ICR, thereby physically preventing the enhancer from tracking along the chromatin fiber (Kurukuti et al. 2006). Finally, as already mentioned, the CTCF insulator-mediated blocking of enhancer-induced histone acetylation (Zhao and Dean 2004) could impede the mobility/flexibility of transcription units separated from the enhancer by the insulator.

Chromatin insulators were also suggested to play a role in organizing complex chromatin structures with distal cis-regulatory elements that have been alleged to prevent enhancer-mediated transcriptional activation. In the “inactive loop” (Kurukuti et al. 2006) and “knotted loop” (Qiu et al. 2008) models, the insulator is proposed to act as a topological barrier, creating a tight and transcriptionally inactive loop. In the “unproductive loop” model, the insulator competes with the enhancer for promoters, acting in effect as a promoter decoy for enhancers (Yoon et al. 2007). A more elaborate discussion on CTCF-dependent chromatin loops is presented in Phillips and Corces (2009). A unifying hypothesis invokes the possibility that the insulator has a dual function, i.e., the insulator can provide a physical barrier and, that as a generator of three-dimensional structures, it can also target distal cis-regulatory elements.

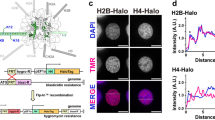

What is the function of the CTCF–cohesin connection?

Sister chromatid cohesion is the process that holds together sister chromatids after replication in S phase. Cohesion is promoted by a protein complex that forms a ring-shaped structure consisting of multiple cohesins. This process is necessary for proper chromosome segregation in mitosis as well as for post-replicative DNA-repair mechanisms. Recent studies have extended this canonical function of the cohesin complex toward a role in gene regulatory circuits. For example, in Drosophila and yeast, a role for cohesin subunits in transcriptional processes beyond sister chromatid cohesion was suggested (Dorsett 2007). In fact, these studies pointed to a role for cohesin in gene regulation via a mechanism resulting in organization of a higher order chromatin structure. Subsequently, cohesin components were found to interact with chromatin by CTCF-dependent recruitment (Fig. 1) during interphase (Parelho et al. 2008; Rubio et al. 2008; Stedman et al. 2008; Wendt et al. 2008). Furthermore, CTCF-dependent enhancer blocking at the H19 ICR was found to depend on cohesin components (Wendt et al. 2008), suggesting that cohesin mediates enhancer blocking via CTCF-dependent recruitment to insulator sites.

Three-dimensional chromatin interaction is observed on two levels of complexity. CTCF–cohesin complexes (green) contract chromatin fibers in cis by linking nearby CTCF binding sites. For longer-range interactions, such as between different chromosomes (light and dark blue), specificity beyond the CTCF–cohesin interaction appears to be necessary. This process may be mediated by unknown factors in concert with the CTCF–cohesin complex bound to one of the chromatin partners

Expression analysis after CTCF/cohesin knockdown through RNAi in HeLa cells demonstrated an overlap between the target genes of both factors, with a number of them being indeed bound by CTCF and cohesin (Wendt et al. 2008). This finding indicates not only that cohesin connects identical sequences on sister chromatids but that remote cis-regulatory regions may also be connected by cohesin bound to CTCF (Fig. 1). This CTCF/cohesin binding may result in chromatin loop formation, which in turn may play a role in several key aspects of chromatin function, such as enhancer action, enhancer blocking, or immunoglobulin recombination. Indeed, a recent study has demonstrated that CTCF-bound cohesin is required to activate the IFNG gene and that loop formation as well as IFNG expression are augmented by cohesin as shown by depletion of Rad21, a subunit of the cohesin complex (Hadjur et al. 2009).

Additional evidence that cohesin plays a role in transcriptional regulation has come from recent studies analyzing patients suffering from Cornelia de Lange syndrome, a disease caused by mutations in several genes coding for components of the cohesin complex (Liu et al. 2009). A significant overlap between genes changing their expression levels after cohesin reduction or CTCF depletion was detected (Wendt et al. 2008). However, in addition to CTCF binding, a more general role for cohesin in transcription was suggested as the promoters of genes deregulated in CdLS patients were markedly enriched for cohesin binding in the absence of CTCF (Liu et al. 2009). A correlation between cohesin binding and transcription has been seen in Drosophila as well (Misulovin et al. 2008; Schaaf et al. 2009).

Interaction of remote sites and loop formation is also required for V(D)J recombination at the immunoglobulin loci. Again, multiple binding sites for CTCF/RAD21 have been identified at the Igh and Igκ locus. Interestingly, CTCF binding at these sites appears largely unchanged throughout differentiation. In contrast, RAD21 recruitment to CTSs was found to be both lineage and stage specific (Degner et al. 2009). Thus, CTCF binding to DNA does not appear to determine the site-specific action of cohesin, but rather a site-specific modification of CTCF or the presence of other factors may regulate cohesin binding or function.

How are long-range chromatin contacts made, even between different chromosomes?

The spatial conformation of the interphase chromatin enables regions to be separated far from each other to make physical contact both within and between chromosomes (Gondor and Ohlsson 2009). There is also accumulating evidence to suggest that these interactions are often CTCF-dependent both in cis and in trans. Using methods based on the chromosome conformation capture (3C) technique (Dekker 2006), the insulator sites at the HS5 site at the 5′-boundary of the mouse β-globin gene (Splinter et al. 2006) as well as at the H19 ICR (Kurukuti et al. 2006) were found to generate loops involving CTCF and CTCF binding sites. Moreover, both of these regions can also interact with a wide range of sequences derived from almost all autosomal chromosomes (Ling et al. 2006; Sandhu et al. 2009; Zhao et al. 2006).

How are these regions making contact with each other, and how can the specificity in such long-range interactions be achieved? Stochastic movements of chromatin fibers presumably provide opportunities for chromatin fiber collisions with a frequency directly proportional to their proximities and affinity to each other. Research showing that CTCF–cohesin complexes contract chromatin fibers in cis at the IFNG (Hadjur et al. 2009) and apolipoprotein (Mishiro et al. 2009) loci suggests that the cohesin link brings more proximal CTSs together. Importantly, for the IFNG locus, it was conclusively shown that this interaction was strictly maintained in cis (Hadjur et al. 2009). It is thus conceivable that CTCF and components of the cohesin complex provide sufficient affinity between interacting CTSs to stabilize, perhaps even to immobilize, chromatin fiber interactions (Wallace and Felsenfeld 2007) resulting from proximal stochastic collisions (Fig. 1).

For longer-range interactions, an element of specificity beyond the CTCF–cohesin interaction appears to be necessary to avoid extensive tangling of chromatin fibers to tens of thousands of CTSs. This notion is further supported by the absence of any enrichment of CTSs in sequences from other chromosomes directly or indirectly interacting with the CTSs within the H19 ICR (Sandhu et al., unpublished observation). It thus appears that CTCF when bound to a chromatin fiber has shorter-range affinity for CTSs in cis, but longer-range affinities for other partners both in cis and in trans. Specificity for longer-range interaction may incorporate 3D features of higher order chromatin structures that provide an affinity for a similar region on another chromosome (Gondor and Ohlsson 2009) (Fig. 1).

How are imprinted chromatin marks read?

Our understanding of genomic imprinting, i.e., parent of origin-specific epigenetic marks frequently manifested in mono-allelic expression patterns, has been dramatically improved by the analysis of CTCF and chromatin insulation. Although the current research focus is heavily on H19 ICR, CTCF is also known to associate with several other imprinted domains, such as DLK1/GTL2 (Wylie et al. 2000), Meg1/Grb10 (Hikichi et al. 2003), Rasgrf1 (Yoon et al. 2005), MEG-3 (Rosa et al. 2005), and KvDMR (Fitzpatrick et al. 2007). For most of these domains, CTCF is known to bind in an allele-specific manner to a region pivotal for the regulation of the imprinted status.

CpG methylation, a key parent of origin-specific epigenetic mark, is not only strongly linked with regulating occupancy of CTSs (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2004) but also DNA binding of CTCF protects against de novo methylation (Pant et al. 2003; Schoenherr et al. 2003). In addition to this dual link between CTCF and an epigenetic state, CTCF also regulates asynchronous replication timing. In other words, for imprinted genes, one parental allele replicates earlier, whereas the opposite allele replicates generally late during the S phase. Thus, CTSs within the H19 ICR domain appear to influence the timing by delaying replication of the maternally inherited Igf2/H19 domain (Bergstrom et al. 2007).

In this context, it is of interest to note that the H19 ICR domain interacts preferentially with other imprinted domains in the germline as well as in stem and somatic cells and that CTSs within the H19 ICR domain confer replication timing patterns on the interacting sequences (Sandhu et al. 2009). The question then becomes what are the underlying structural features that enable chromatin to bring about these processes? One possibility is that particular combinations of repeat elements underlie a chromatin scaffold that together with CTCF and other factors provides an epigenetic signature with a high affinity to a chromatin structure on another chromosome (Gondor and Ohlsson 2009). This hypothesis is partially borne out by the observation that imprinted states can be predicted depending on constellations of repeat elements within imprinted domains (Walter et al. 2006). However, it remains to be established whether such features in combination with CTSs were selected to transfer epigenetic states in trans to facilitate evolution of genomic imprinting (Sandhu et al. 2009).

What are the mechanisms of X-chromosomal inactivation?

X-chromosomal inactivation is the process that compensates for the dosage difference in sex chromosomes between male and female mammals. A number of key players involved in this process have been identified through the past decades; however, there is still some debate about the exact mechanisms underlying this biological phenomenon. So far, it has been established that the two X-chromosomes come into close contact in the nuclear space, just at the onset of inactivation of one of the two X-chromosomes (Chow and Heard 2009). Moreover, pairing was found to be dependent on the X inactivation center (XIC), which itself is involved in the counting of X-chromosomes and the choice of inactivation (Bacher et al. 2006). Within the XIC, a short fragment was found to recapitulate pairing and that pairing was dependent on transcription as well as on CTCF (Xu et al. 2007). Recently, a model was proposed for XIC regulation (Donohoe et al. 2009). This model involves the transcriptional regulator Oct4 that interacts not only with CTCF bound to many sites, but also with the XIC regulator genes Tsix and Xite, which are located in antisense orientation next to the gene coding for the X inactive specific transcript (Xist). Oct-4 activated Tsix and Xite transcription inhibits transcription of Xist on the same chromosome. Upon CTCF-mediated pairing and cell differentiation, Oct4 levels are reduced such that only the active X will continue with Tsix transcription, whereas the lack of Tsix activity would enable Xist expression on the inactive chromosome.

How are heterochromatin boundaries maintained?

Heterochromatic (inactive) regions are insulated from euchromatic (active) regions (Fig. 2). If insulation at these boundaries is defective, as observed after chromosomal rearrangements, for example, a spreading of inactive chromatin modification into the active chromatin is observed; a phenomenon called position-effect variegation (Probst et al. 2009). A role for CTCF in barrier function was already proposed in the 1990s based on the finding that several CTS-containing insulator elements were able to block the position effects on reporter genes stably integrated in the genome (Chung et al. 1993; Li et al. 2002). In contrast, it was shown that the enhancer blocking and barrier functions of the chicken beta-globin HS4 were separable, indicating that the boundary function of this element was independent of CTCF (Recillas-Targa et al. 2002).

Heterochromatic (inactive) chromatin regions are insulated from euchromatic (active) regions. Active domains, as exemplified by active genes, histone acetylation, or histone H3 lysine 4 methylation (H3K4me2), are separated from inactive domains, which are identified by repressed genes, histone H3 lysine 27 methylation (H3K27me3), lamin B1, or polycomb binding. These heterochromatic regions are often associated with the nuclear lamina (gray arc). Several chromatin features have been identified at the border position between domains. These are CpG islands and active promoters, loss, or high turnover rate of nucleosomes and CTCF/cohesin binding. A border function may be mediated by chromatin activation at these regions to counteract any spreading of inactive chromatin marks into the active domains

Recent advances in high-throughput genomics have resulted in genome-wide binding profiles of CTCF in different organisms. These studies demonstrated a significant association of CTCF with boundary elements defining the borders between adjacent chromatin domains of opposing activity as determined by the association with specific histone modification marks (Barski et al. 2007; Bartkuhn et al. 2009; Cuddapah et al. 2009). Binding to boundaries between active and repressed chromatin was seen especially in the context of H3K27me3, a histone modification that occurs in large chromosomal domains ranging from several kb up to several 100 kb in Drosophila (Fig. 2). H3K27me3 modification is regarded as a hallmark of Polycomb-repressed chromatin. These regions are marked by low gene density. Furthermore, gene activity is found with lower levels as compared to genes at other genomic locations (Schwartz et al. 2006).

Similarly, CTCF was identified to bind to the margins of lamin-associated domains (LADs). Association of chromatin with the nuclear lamina is believed to negatively influence gene expression through recruitment of chromatin to the nuclear periphery. Interestingly, high levels of H3K27me3 are also characteristic of those domains, suggesting that LADs are similar to H3K27me3 domains (Guelen et al. 2008). Additionally, LAD borders were marked by active transcription from divergent promoters transcribing away from the repressed domains or by CpG islands, which again are indicative of active promoters (Fig. 2).

CTCF-dependent heterochromatin boundaries have been recently suggested to play a major role in the regulation of tumor suppressor genes (Witcher and Emerson 2009). Binding of CTCF to sites upstream of the promoters of the p16, CHD1, and RASSF1A genes is correlated with activation of the downstream genes, whereas the regions upstream of the CTSs are marked by repressive chromatin modification with the CTS demarcating the transition zones between heterochromatic and euchromatic histone modifications. Consequently, loss of CTCF binding leads to repressive chromatin marks spreading into the p16 promoter as well as to a loss of gene expression.

The mechanism of barrier function could be a physical block generated by CTCF binding. Furthermore, the presence of active promoters and/or the association of CTCF with RNA polymerase II (Chernukhin et al. 2007) and with active promoters (Bartkuhn et al. 2009) may provide a local active chromatin region counteracting any heterochromatic spreading.

Outlook

There are many important aspects concerning chromatin organization in general and the role of CTCF in particular that need addressing in the future. To start with, CTCF binding sites are known to be flanked by an array of phased nucleosomes. But what is the cause and effect of nucleosome positioning and CTCF binding? Did the nucleosome positioning feature evolve before or after the emergence of CTCF binding sites? As nucleosome positioning is determined by the underlying sequence and independent of CTCF binding sites within at least the H19 ICR, it is reasonable to assume that nucleosome positioning evolved prior to CTCF binding.

The insulator function in some cases has been shown to involve chromatin long range and CTCF and/or cohesin binding. But how does this mechanistically interfere with promoter/enhancer interaction? Could it operate by stabilizing transient interactions in cis, thereby allowing more time for epigenetic factors, such as Suz12 (Li et al. 2008) to silence the interacting region? Or does this interaction serve to repress the interacting region by contracting chromatin conformations?

ICRs display not only CTCF-dependent chromatin insulator function but also a CTCF-dependent ability to delay replication timing, which is strikingly different between the alleles (Sandhu et al. 2009). How do CTCF binding sites within such ICRs regulate BOTH insulation and replication timing? And how can the H19 ICR regulate replication timing in trans in a CTCF-dependent manner? Is there a division of labor between different CTCF binding sites, such that some govern insulation and others replication timing patterns?

Furthermore, it is not clear whether CTCF has the ability to interconnect its binding sites on a genome-wide scale. This is hinted at by the demonstrations that CTCF appears to contract chromatin structures by recruiting cohesin (Hadjur et al. 2009). However, there is currently no documentation that this occurs in trans. Even if this would be the case, how are the specificities in interactions between CTCF binding sites on different chromosomes achieved?

Finally, besides a striking colocalization of CTCF with chromatin domain boundaries, there is functional evidence of CTCF mediating a chromatin barrier function. Whether barrier sites are mechanistically different from sites mediating enhancer blocking remains to be shown. If so, what are the decisive hallmarks discriminating CTCF binding sites governing insulation and barrier functions, respectively? This question can be extended to all of the CTCF-mediated features: Are all of these functions realized at each of the 30,000 genomic binding sites (Cuddapah et al. 2009) or to which extent, are binding site-specific functions mediated by the DNA sequence or by neighboring factors? By extrapolating the timeline of CTCF discoveries, we have here identified what we believe are key issues within this research area. By formulating specific questions, we hope to stimulate discussions among colleagues dedicated to research on CTCF, which is truly a remarkable factor.

References

Bacher CP, Guggiari M, Brors B, Augui S, Clerc P, Avner P, Eils R, Heard E (2006) Transient colocalization of X-inactivation centres accompanies the initiation of X inactivation. Nat Cell Biol 8:293–299

Baniahmad A, Steiner C, Kohne AC, Renkawitz R (1990) Modular structure of a chicken lysozyme silencer: involvement of an unusual thyroid hormone receptor binding site. Cell 61:505–514

Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K (2007) High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129:823–837

Bartkuhn M, Straub T, Herold M, Herrmann M, Rathke C, Saumweber H, Gilfillan GD, Becker PB, Renkawitz R (2009) Active promoters and insulators are marked by the centrosomal protein 190. Embo J 28:877–888

Bell AC, Felsenfeld G (2000) Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature 405:482–485

Bell AC, West AG, Felsenfeld G (1999) The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell 98:387–396

Bergstrom R, Whitehead J, Kurukuti S, Ohlsson R (2007) CTCF regulates asynchronous replication of the imprinted H19/Igf2 domain. Cell Cycle 6:450–454

Burcin M, Arnold R, Lutz M, Kaiser B, Runge D, Lottspeich F, Filippova GN, Lobanenkov VV, Renkawitz R (1997) Negative protein 1, which is required for function of the chicken lysozyme gene silencer in conjunction with hormone receptors, is identical to the multivalent zinc finger repressor CTCF. Mol Cell Biol 17:1281–1288

Burke LJ, Zhang R, Bartkuhn M, Tiwari VK, Tavoosidana G, Kurukuti S, Weth C, Leers J, Galjart N, Ohlsson R, Renkawitz R (2005) CTCF binding and higher order chromatin structure of the H19 locus are maintained in mitotic chromatin. EMBO J 24:3291–3300

Bushey AM, Ramos E, Corces VG (2009) Three subclasses of a Drosophila insulator show distinct and cell type-specific genomic distributions. Genes Dev 23:1338–1350

Cai S, Lee CC, Kohwi-Shigematsu T (2006) SATB1 packages densely looped, transcriptionally active chromatin for coordinated expression of cytokine genes. Nat Genet 38:1278–1288

Carter D, Chakalova L, Osborne CS, Dai YF, Fraser P (2002) Long-range chromatin regulatory interactions in vivo. Nat Genet 32:623–626

Chao W, Huynh KD, Spencer RJ, Davidow LS, Lee JT (2002) CTCF, a candidate trans-acting factor for X-inactivation choice. Science 295:345–347

Chernukhin I, Shamsuddin S, Kang SY, Bergstrom R, Kwon YW, Yu W, Whitehead J, Mukhopadhyay R, Docquier F, Farrar D, Morrison I, Vigneron M, Wu SY, Chiang CM, Loukinov D, Lobanenkov V, Ohlsson R, Klenova E (2007) CTCF interacts with and recruits the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II to CTCF target sites genome-wide. Mol Cell Biol 27:1631–1648

Cho DH, Thienes CP, Mahoney SE, Analau E, Filippova GN, Tapscott SJ (2005) Antisense transcription and heterochromatin at the DM1 CTG repeats are constrained by CTCF. Mol Cell 20:483–489

Chow J, Heard E (2009) X inactivation and the complexities of silencing a sex chromosome. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21:359–366

Chuang CH, Carpenter AE, Fuchsova B, Johnson T, de Lanerolle P, Belmont AS (2006) Long-range directional movement of an interphase chromosome site. Curr Biol 16:825–831

Chung JH, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G (1993) A 5′ element of the chicken beta-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell 74:505–514

Cuddapah S, Jothi R, Schones DE, Roh TY, Cui K, Zhao K (2009) Global analysis of the insulator binding protein CTCF in chromatin barrier regions reveals demarcation of active and repressive domains. Genome Res 19:24–32

Degner SC, Wong TP, Jankevicius G, Feeney AJ (2009) Cutting edge: developmental stage-specific recruitment of cohesin to CTCF sites throughout immunoglobulin loci during B lymphocyte development. J Immunol 182:44–48

Dekker J (2006) The three ‘C’ s of chromosome conformation capture: controls, controls, controls. Nat Methods 3:17–21

Donohoe ME, Silva SS, Pinter SF, Xu N, Lee JT (2009) The pluripotency factor Oct4 interacts with Ctcf and also controls X-chromosome pairing and counting. Nature 460:128–132

Dorsett D (2007) Roles of the sister chromatid cohesion apparatus in gene expression, development, and human syndromes. Chromosoma 116:1–13

Faro-Trindade I, Cook PR (2006) Transcription factories: structures conserved during differentiation and evolution. Biochem Soc Trans 34:1133–1137

Fiering S, Whitelaw E, Martin DI (2000) To be or not to be active: the stochastic nature of enhancer action. Bioessays 22:381–387

Filippova GN, Lindblom A, Meincke LJ, Klenova EM, Neiman PE, Collins SJ, Doggett NA, Lobanenkov VV (1998) A widely expressed transcription factor with multiple DNA sequence specificity, CTCF, is localized at chromosome segment 16q22.1 within one of the smallest regions of overlap for common deletions in breast and prostate cancers. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 22:26–36

Filippova GN, Thienes CP, Penn BH, Cho DH, Hu YJ, Moore JM, Klesert TR, Lobanenkov VV, Tapscott SJ (2001) CTCF-binding sites flank CTG/CAG repeats and form a methylation-sensitive insulator at the DM1 locus. Nat Genet 28:335–343

Filippova GN, Cheng MK, Moore JM, Truong JP, Hu YJ, Nguyen DK, Tsuchiya KD, Disteche CM (2005) Boundaries between chromosomal domains of X inactivation and escape bind CTCF and lack CpG methylation during early development. Dev Cell 8:31–42

Fitzpatrick GV, Pugacheva EM, Shin JY, Abdullaev Z, Yang Y, Khatod K, Lobanenkov VV, Higgins MJ (2007) Allele-specific binding of CTCF to the multipartite imprinting control region KvDMR1. Mol Cell Biol 27:2636–2647

Fu Y, Sinha M, Peterson CL, Weng Z (2008) The insulator binding protein CTCF positions 20 nucleosomes around its binding sites across the human genome. PLoS Genet 4:e1000138

Gerasimova TI, Lei EP, Bushey AM, Corces VG (2007) Coordinated control of dCTCF and gypsy chromatin insulators in Drosophila. Mol Cell 28:761–772

Gondor A, Ohlsson R (2009) Chromosome crosstalk in three dimensions. Nature 461:212–217

Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, Eussen BH, de Klein A, Wessels L, de Laat W, van Steensel B (2008) Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature 453:948–951

Hadjur S, Williams LM, Ryan NK, Cobb BS, Sexton T, Fraser P, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M (2009) Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus. Nature 460:410–413

Hark AT, Schoenherr CJ, Katz DJ, Ingram RS, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM (2000) CTCF mediates methylation-sensitive enhancer-blocking activity at the H19/Igf2 locus. Nature 405:486–489

Hikichi T, Kohda T, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F (2003) Imprinting regulation of the murine Meg1/Grb10 and human GRB10 genes; roles of brain-specific promoters and mouse-specific CTCF-binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res 31:1398–1406

Holohan EE, Kwong C, Adryan B, Bartkuhn M, Herold M, Renkawitz R, Russell S, White R (2007) CTCF genomic binding sites in Drosophila and the organisation of the bithorax complex. PloS Genet 3:e112

Ishihara K, Oshimura M, Nakao M (2006) CTCF-dependent chromatin insulator is linked to epigenetic remodeling. Mol Cell 23:733–742

Jelinic P, Stehle JC, Shaw P (2006) The testis-specific factor CTCFL cooperates with the protein methyltransferase PRMT7 in H19 imprinting control region methylation. PLoS Biol 4:e355

Kanduri C, Pant V, Loukinov D, Pugacheva E, Qi CF, Wolffe A, Ohlsson R, Lobanenkov VV (2000) Functional association of CTCF with the insulator upstream of the H19 gene is parent of origin-specific and methylation-sensitive. Curr Biol 10:853–856

Kanduri M, Kanduri C, Mariano P, Vostrov AA, Quitschke W, Lobanenkov V, Ohlsson R (2002) Multiple nucleosome positioning sites regulate the CTCF-mediated insulator function of the H19 imprinting control region. Mol Cell Biol 22:3339–3344

Kim TH, Abdullaev ZK, Smith AD, Ching KA, Loukinov DI, Green RD, Zhang MQ, Lobanenkov VV, Ren B (2007) Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell 128:1231–1245

Kurukuti S, Tiwari VK, Tavoosidana G, Pugacheva E, Murrell A, Zhao Z, Lobanenkov V, Reik W, Ohlsson R (2006) CTCF binding at the H19 imprinting control region mediates maternally inherited higher-order chromatin conformation to restrict enhancer access to Igf2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:10684–10689

Lefevre P, Witham J, Lacroix CE, Cockerill PN, Bonifer C (2008) The LPS-induced transcriptional upregulation of the chicken lysozyme locus involves CTCF eviction and noncoding RNA transcription. Mol Cell 32:129–139

Li Q, Zhang M, Han H, Rohde A, Stamatoyannopoulos G (2002) Evidence that DNase I hypersensitive site 5 of the human beta-globin locus control region functions as a chromosomal insulator in transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res 30:2484–2491

Li Q, Barkess G, Qian H (2006) Chromatin looping and the probability of transcription. Trends Genet 22:197–202

Li T, Hu JF, Qiu X, Ling J, Chen H, Wang S, Hou A, Vu TH, Hoffman AR (2008) CTCF regulates allelic expression of Igf2 by orchestrating a promoter-polycomb repressive complex 2 intrachromosomal loop. Mol Cell Biol 28:6473–6482

Ling JQ, Li T, Hu JF, Vu TH, Chen HL, Qiu XW, Cherry AM, Hoffman AR (2006) CTCF mediates interchromosomal colocalization between Igf2/H19 and Wsb1/Nf1. Science 312:269–272

Liu J, Zhang Z, Bando M, Itoh T, Deardorff MA, Clark D, Kaur M, Tandy S, Kondoh T, Rappaport E, Spinner NB, Vega H, Jackson LG, Shirahige K, Krantz ID (2009) Transcriptional dysregulation in NIPBL and cohesin mutant human cells. PLoS Biol 7:e1000119

Lobanenkov VV, Nicolas RH, Adler VV, Paterson H, Klenova EM, Polotskaja AV, Goodwin GH (1990) A novel sequence-specific DNA binding protein which interacts with three regularly spaced direct repeats of the CCCTC-motif in the 5′- flanking sequence of the chicken c-myc gene. Oncogene 5:1743–1753

Loukinov DI, Pugacheva E, Vatolin S, Pack SD, Moon H, Chernukhin I, Mannan P, Larsson E, Kanduri C, Vostrov AA, Cui H, Niemitz EL, Rasko JE, Docquier FM, Kistler M, Breen JJ, Zhuang Z, Quitschke WW, Renkawitz R, Klenova EM, Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Morse HC 3rd, Lobanenkov VV (2002) BORIS, a novel male germ-line-specific protein associated with epigenetic reprogramming events, shares the same 11-zinc-finger domain with CTCF, the insulator protein involved in reading imprinting marks in the soma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:6806–6811

Lutz M, Burke LJ, LeFevre P, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Bonifer C, Filippova GN, Lobanenkov V, Renkawitz R (2003) Thyroid hormone-regulated enhancer blocking: cooperation of CTCF and thyroid hormone receptor. Embo J 22:1579–1587

Mishiro T, Ishihara K, Hino S, Tsutsumi S, Aburatani H, Shirahige K, Kinoshita Y, Nakao M (2009) Architectural roles of multiple chromatin insulators at the human apolipoprotein gene cluster. Embo J 28:1234–1245

Misulovin Z, Schwartz YB, Li XY, Kahn TG, Gause M, MacArthur S, Fay JC, Eisen MB, Pirrotta V, Biggin MD, Dorsett D (2008) Association of cohesin and Nipped-B with transcriptionally active regions of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Chromosoma 117:89–102

Mohan M, Bartkuhn M, Herold M, Philippen A, Heinl N, Bardenhagen I, Leers J, White RA, Renkawitz-Pohl R, Saumweber H, Renkawitz R (2007) The Drosophila insulator proteins CTCF and CP190 link enhancer blocking to body patterning. Embo J 26:4203–4214

Moon H, Filippova G, Loukinov D, Pugacheva E, Chen Q, Smith ST, Munhall A, Grewe B, Bartkuhn M, Arnold R, Burke LJ, Renkawitz-Pohl R, Ohlsson R, Zhou J, Renkawitz R, Lobanenkov V (2005) CTCF is conserved from Drosophila to humans and confers enhancer blocking of the Fab-8 insulator. EMBO Rep 6:165–170

Mukhopadhyay R, Yu W, Whitehead J, Xu J, Lezcano M, Pack S, Kanduri C, Kanduri M, Ginjala V, Vostrov A, Quitschke W, Chernukhin I, Klenova E, Lobanenkov V, Ohlsson R (2004) The binding sites for the chromatin insulator protein CTCF map to DNA methylation-free domains genome-wide. Genome Res 14:1594–1602

Ohlsson R, Renkawitz R, Lobanenkov V (2001) CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet 17:520–527

Pant V, Mariano P, Kanduri C, Mattsson A, Lobanenkov V, Heuchel R, Ohlsson R (2003) The nucleotides responsible for the direct physical contact between the chromatin insulator protein CTCF and the H19 imprinting control region manifest parent of origin-specific long-distance insulation and methylation-free domains. Genes Dev 17:586–590

Parelho V, Hadjur S, Spivakov M, Leleu M, Sauer S, Gregson HC, Jarmuz A, Canzonetta C, Webster Z, Nesterova T, Cobb BS, Yokomori K, Dillon N, Aragon L, Fisher AG, Merkenschlager M (2008) Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell 132:422–433

Phillips JE, Corces VG (2009) CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell 137:1194–1211

Probst AV, Dunleavy E, Almouzni G (2009) Epigenetic inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10:192–206

Qiu X, Vu TH, Lu Q, Ling JQ, Li T, Hou A, Wang SK, Chen HL, Hu JF, Hoffman AR (2008) A complex deoxyribonucleic acid looping configuration associated with the silencing of the maternal Igf2 allele. Mol Endocrinol 22:1476–1488

Recillas-Targa F, Pikaart MJ, Burgess-Beusse B, Bell AC, Litt MD, West AG, Gaszner M, Felsenfeld G (2002) Position-effect protection and enhancer blocking by the chicken beta-globin insulator are separable activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99:6883–6888

Rosa AL, Wu YQ, Kwabi-Addo B, Coveler KJ, Reid Sutton V, Shaffer LG (2005) Allele-specific methylation of a functional CTCF binding site upstream of MEG3 in the human imprinted domain of 14q32. Chromosome Res 13:809–818

Rubio ED, Reiss DJ, Welcsh PL, Disteche C, Filippova G, Baliga NS, Aebersold R, Ranish JA, Krumm A (2008) CTCF physically links cohesin to chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:8309–8314

Sagai T, Amano T, Tamura M, Mizushina Y, Sumiyama K, Shiroishi T (2009) A cluster of three long-range enhancers directs regional Shh expression in the epithelial linings. Development 136:1665–1674

Sandhu KS, Shi C, Sjolinder M, Zhao Z, Göndör A, Liu L, Tiwari VK, Guibert S, Emilsson L, Imreh MP, Ohlsson R (2009) Nonallelic transvection of multiple imprinted loci is organized by the H19 imprinting control region during germline development. Genes Dev 23:2598–2603

Schaaf CA, Misulovin Z, Sahota G, Siddiqui AM, Schwartz YB, Kahn TG, Pirrotta V, Gause M, Dorsett D (2009) Regulation of the Drosophila Enhancer of split and invected-engrailed gene complexes by sister chromatid cohesion proteins. PLoS ONE 4:e6202

Schoenherr CJ, Levorse JM, Tilghman SM (2003) CTCF maintains differential methylation at the Igf2/H19 locus. Nat Genet 33:66–69

Schwartz YB, Kahn TG, Nix DA, Li XY, Bourgon R, Biggin M, Pirrotta V (2006) Genome-wide analysis of Polycomb targets in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet 38:700–705

Segal E, Widom J (2009) What controls nucleosome positions? Trends Genet 25:335–343

Sparago A, Cerrato F, Vernucci M, Ferrero GB, Silengo MC, Riccio A (2004) Microdeletions in the human H19 DMR result in loss of IGF2 imprinting and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Nat Genet 36:958–960

Splinter E, Heath H, Kooren J, Palstra RJ, Klous P, Grosveld F, Galjart N, de Laat W (2006) CTCF mediates long-range chromatin looping and local histone modification in the beta-globin locus. Genes Dev 20:2349–2354

Stedman W, Kang H, Lin S, Kissil J, Bartolomei M, Lieberman P (2008) Cohesins localize with CTCF at the KSHV latency control region and at cellular c-myc and H19/Igf2 insulators. Embo J 27:654–666

Sun L, Huang L, Nguyen P, Bisht KS, Bar-Sela G, Ho AS, Bradbury CM, Yu W, Cui H, Lee S, Trepel JB, Feinberg AP, Gius D (2008) DNA methyltransferase 1 and 3B activate BAG-1 expression via recruitment of CTCFL/BORIS and modulation of promoter histone methylation. Cancer Res 68:2726–2735

Sutherland H, Bickmore WA (2009) Transcription factories: gene expression in unions? Nat Rev Genet 10:457–466

Szabo P, Tang SH, Rentsendorj A, Pfeifer GP, Mann JR (2000) Maternal-specific footprints at putative CTCF sites in the H19 imprinting control region give evidence for insulator function. Curr Biol 10:607–610

Tolhuis B, Palstra RJ, Splinter E, Grosveld F, de Laat W (2002) Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active beta-globin locus. Mol Cell 10:1453–1465

Torrano V, Navascues J, Docquier F, Zhang R, Burke LJ, Chernukhin I, Farrar D, Leon J, Berciano MT, Renkawitz R, Klenova E, Lafarga M, Delgado MD (2006) Targeting of CTCF to the nucleolus inhibits nucleolar transcription through a poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation-dependent mechanism. J Cell Sci 119:1746–1759

Vatolin S, Abdullaev Z, Pack SD, Flanagan PT, Custer M, Loukinov DI, Pugacheva E, Hong JA, Morse H 3rd, Schrump DS, Risinger JI, Barrett JC, Lobanenkov VV (2005) Conditional expression of the CTCF-paralogous transcriptional factor BORIS in normal cells results in demethylation and derepression of MAGE-A1 and reactivation of other cancer-testis genes. Cancer Res 65:7751–7762

Vostrov AA, Quitschke WW (1997) The zinc finger protein CTCF binds to the APBbeta domain of the amyloid beta-protein precursor promoter. Evidence for a role in transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem 272:33353–33359

Wallace JA, Felsenfeld G (2007) We gather together: insulators and genome organization. Curr Opin Genet Dev 17:400–407

Walter J, Hutter B, Khare T, Paulsen M (2006) Repetitive elements in imprinted genes. Cytogenet Genome Res 113:109–115

Wendt KS, Yoshida K, Itoh T, Bando M, Koch B, Schirghuber E, Tsutsumi S, Nagae G, Ishihara K, Mishiro T, Yahata K, Imamoto F, Aburatani H, Nakao M, Imamoto N, Maeshima K, Shirahige K, Peters JM (2008) Cohesin mediates transcriptional insulation by CCCTC-binding factor. Nature 451:796–801

Witcher M, Emerson BM (2009) Epigenetic silencing of the p16(INK4a) tumor suppressor is associated with loss of CTCF binding and a chromatin boundary. Mol Cell 34:271–284

Wylie AA, Murphy SK, Orton TC, Jirtle RL (2000) Novel imprinted DLK1/GTL2 domain on human chromosome 14 contains motifs that mimic those implicated in IGF2/H19 regulation. Genome Res 10:1711–1718

Xi H, Shulha HP, Lin JM, Vales TR, Fu Y, Bodine DM, McKay RD, Chenoweth JG, Tesar PJ, Furey TS, Ren B, Weng Z, Crawford GE (2007) Identification and characterization of cell type-specific and ubiquitous chromatin regulatory structures in the human genome. PLoS Genet 3:e136

Xie X, Mikkelsen TS, Gnirke A, Lindblad-Toh K, Kellis M, Lander ES (2007) Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in conserved regions of the human genome, including thousands of CTCF insulator sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:7145–7150

Xu N, Donohoe ME, Silva SS, Lee JT (2007) Evidence that homologous X-chromosome pairing requires transcription and Ctcf protein. Nat Genet 39:1390–1396

Yoon B, Herman H, Hu B, Park YJ, Lindroth A, Bell A, West AG, Chang Y, Stablewski A, Piel JC, Loukinov DI, Lobanenkov VV, Soloway PD (2005) Rasgrf1 imprinting is regulated by a CTCF-dependent methylation-sensitive enhancer blocker. Mol Cell Biol 25:11184–11190

Yoon YS, Jeong S, Rong Q, Park KY, Chung JH, Pfeifer K (2007) Analysis of the H19ICR insulator. Mol Cell Biol 27:3499–3510

Yu W, Ginjala V, Pant V, Chernukhin I, Whitehead J, Docquier F, Farrar D, Tavoosidana G, Mukhopadhyay R, Kanduri C, Oshimura M, Feinberg AP, Lobanenkov V, Klenova E, Ohlsson R (2004) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation regulates CTCF-dependent chromatin insulation. Nat Genet 36:1105–1110

Yusufzai TM, Tagami H, Nakatani Y, Felsenfeld G (2004) CTCF tethers an insulator to subnuclear sites, suggesting shared insulator mechanisms across species. Mol Cell 13:291–298

Zhao H, Dean A (2004) An insulator blocks spreading of histone acetylation and interferes with RNA polymerase II transfer between an enhancer and gene. Nucleic Acids Res 32:4903–4919

Zhao Z, Tavoosidana G, Sjolinder M, Gondor A, Mariano P, Wang S, Kanduri C, Lezcano M, Sandhu KS, Singh U, Pant V, Tiwari V, Kurukuti S, Ohlsson R (2006) Circular chromosome conformation capture (4C) uncovers extensive networks of epigenetically regulated intra- and interchromosomal interactions. Nat Genet 38:1341–1347

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Reinhard Dammann for critical comments on the manuscript. Our research is supported by grants from the DFG and Swedish Science Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Research Foundation, the Swedish Pediatric Cancer Foundation, the Lundberg Foundation as well as HEROIC and ChILL (EU-integrated projects).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Communicated by R. Paro

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohlsson, R., Bartkuhn, M. & Renkawitz, R. CTCF shapes chromatin by multiple mechanisms: the impact of 20 years of CTCF research on understanding the workings of chromatin. Chromosoma 119, 351–360 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00412-010-0262-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00412-010-0262-0