Abstract

We previously reported that in a diabetes mouse model, characterised by moderate hyperglycaemia and reduced β-cell mass, the radical scavenger bis(1-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinyl)decandioate di-hydrochloride (IAC), a non-conventional cyclic hydroxylamine derivative, improves metabolic alterations by counteracting β-cell dysfunction associated with oxidative stress. The aims of this study were to ascertain whether the beneficial effects of IAC treatment could be maintained after its discontinuation and further elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Diabetes was induced in C57Bl/6J mice by streptozotocin (STZ) and nicotinamide (NA) administration. Diabetic mice were treated for 7 weeks with various doses of IAC (7.5, 15, or 30 mg/kg b.w./die i.p.) and monitored for additional 8 weeks after suspension of IAC. Then, pancreatic tissue was used for determination of β-cell mass by immunohistochemistry and β-cell ultrastructural analysis. STZ-NA mice showed moderate hyperglycaemia, glucose intolerance and reduced β-cell mass (25% of controls). IAC-treated STZ-NA mice (at both doses of 15 and 30 mg/kg b.w.) showed long-term reduction of hyperglycaemia even after discontinuation of treatment, attenuation of glucose intolerance and partial preservation of β-cell mass. The lowest IAC dose was much less effective. Plasma nitrotyrosine levels (an oxidative stress index) significantly increased in untreated diabetic mice and were lowered upon IAC treatment. At ultrastructural level, β cells of IAC-treated diabetic mice were protected against degranulation and mitochondrial alterations. In the STZ-NA diabetic mouse model, the radical scavenger IAC induces a prolonged reduction of hyperglycaemia associated with partial restoration of β-cell mass and function, likely dependent on blockade of oxidative stress-induced damaging mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is characterised by a combination of peripheral insulin resistance and defective insulin secretion (Kahn 2003). Usually, the disease arises due to the progressive failure of insulin secretion by β cells to overcome reduced sensitivity to the hormone (Kahn 2001; Prentki and Nolan 2006). This leads to hyperglycaemia, which can in turn exert deleterious effects on β cells (Robertson 2004). Among the various mechanisms likely responsible for β-cell dysfunction and damage induced by hyperglycaemia, oxidative stress is considered to play a major role (Kaneto et al. 2005; Prentki and Nolan 2006; Robertson 2004).

Actually, in T2D, increased plasma glucose levels, often associated with high circulating free fatty acid (FFA) concentrations, result in enhanced mitochondrial superoxide production and increased exposure of cells to reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Brownlee 2003; Lowell and Shulman 2005), which can also be generated through the glycation reaction (Kaneto et al. 1996) and the hexosamine pathway (Kaneto et al. 2001). Moreover, the enhanced superoxide production is usually accompanied by increased NO generation due to induction of NO synthase (Beckman and Koppenol 1996). This favours the production of radical nitrogen species (RNS), such as the cytotoxic peroxynitrite anion, which in turn oxidises sulfhydryl groups in proteins, nitrates amino acids like tyrosine, aggravates lipid peroxidation and provokes DNA strand breaks, eventually leading to severe cell damage (Beckman and Koppenol 1996). It should also be considered that β cells are especially sensitive to ROS excess because of a low expression of ROS-detoxifying enzymes in comparison with other cell types (Tiedge et al. 1997).

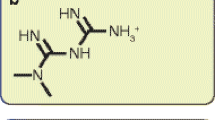

We previously tested the protective effects of a low molecular weight radical scavenger, namely, bis(1-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinyl)decandioate di-hydrochloride (IAC), in a non-obese diabetes mouse model characterised by reduced pancreatic insulin content and moderate hyperglycaemic levels, like those usually occurring in human T2D. This model, obtained by the combined administration of streptozotocin (STZ) and nicotinamide (NA), has been developed in our laboratory as well as in others (Masiello et al. 2006; Matsuyama-Yokono et al. 2008; Nakamura et al. 2006) and is increasingly used for pharmacological research in diabetes (Novelli et al. 2007; Tahara et al. 2008, 2009). In STZ-NA mice, IAC was able to reduce hyperglycaemia and partially preserve pancreatic insulin content, thus counteracting β-cell dysfunction associated with oxidative stress (Novelli et al. 2007). IAC is a non-conventional cyclic hydroxylamine derivative antioxidant synthesised in our laboratories (for its chemical structure, see Fig. 1). It is hydrosoluble in its protonated chloridrate form, membrane permeant and acts as an effective and self-regenerating intracellular scavenger of most oxygen, nitrogen and carbon-centred radicals at an early stage, i.e. prior to the generation of ROS- and RNS-derived toxic products (Valgimigli et al. 2001). The aims of the present study were (1) to ascertain whether the beneficial effects of IAC in diabetic mice could be maintained after discontinuation of the treatment and (2) to provide further insights into the mechanisms of its protective effect.

Materials and methods

Animals

Experiments were performed in male C57Bl/6J mice, of the age of 8–9 weeks, weighing 22–24 g, purchased from Harlan Laboratories s.r.l. (S. Pietro al Natisone, Udine, Italy). Mice were kept at a constant temperature of 24–25°C and were subjected to a controlled 12 h light–dark cycle; they had free access to water and pelleted diet. The experimental protocol followed the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (US NH publication no. 83-85, revised 1985) and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Pisa.

Induction of diabetes

Nicotinamide (210 mg/kg b.w.) (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA), dissolved in saline, was injected intraperitoneally 15 min before administration of STZ (Sigma, 180 mg/kg b.w., i.p.), which was dissolved in buffer citrate (pH 4.5) immediately before use. Controls received both vehicles. During the experimental period, the animals’ food intake and body weight were monitored once a week.

IAC treatment

Glycaemia was measured 7, 14, and 21 days after STZ-NA treatment to assess stability of glycaemic values, and on the 22nd day, diabetic mice were homogeneously distributed into four subgroups of 10–12 mice each. Pharmacological treatment was randomly assigned to the four diabetic groups, three of them receiving intraperitoneal administration of IAC at the dosage of 7.5, 15 or 30 mg/kg b.w./day respectively, dissolved in saline immediately before use and the fourth receiving saline only. Two groups of non-diabetic controls were administered daily either saline or 30 mg/kg IAC i.p. IAC was synthesised in our laboratory, as detailed elsewhere (Valgimigli et al. 2001). After 7 weeks of treatment, IAC administration was discontinued, and mice were monitored for an additional 8-week period. Then, 3-h fasted animals were anaesthetised using pentobarbital (50 mg/kg b.w., i.p.), and the pancreas was rapidly removed, dissected free of fat and processed for immunohistochemical and electron microscope analyses.

Assays in whole blood or plasma

Blood sampling was performed in conscious mice that had food removed 3 h earlier, unless otherwise specified. Whole-blood glucose levels were determined in 5 μl of blood obtained by cutting the tip of the tail, using OneTouch Ultra glucometer apparatus (Life Scan, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA). When required (e.g., for plasma insulin or nitrotyrosine measurements), some drops of blood (80–100 μl) were collected by the same method in small tubes containing 2 μl of concentrated EDTA. Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at −20°C until assayed. Plasma insulin was measured by radioimmunoassay according to Herbert et al. (1965), using a guinea pig insulin antibody from ICN (Costa Mesa, CA, USA) and 125I-labeled insulin from LINCO (LINCO Research, St. Charles, MO, USA). Plasma nitrotyrosine concentration was determined using a commercially available kit (Nitrotyrosine Assay Kit, Upstate, Lake Placid, NY, USA).

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

After 6 weeks of IAC treatment, glucose (1.5 g/kg b.w., administered intraperitoneally as 16.5% solution) was given to 3-h fasted conscious animals. Blood samples were obtained sequentially from the tail vein before and after the glucose injection and immediately used for glucose determination by a glucometer or collected in EDTA-treated small tubes and centrifuged at 4°C (0-, 15- and 60-min samples), with storage of plasma at −20°C for subsequent insulin measurement. The daily IAC dose was administered at the end of the test.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue preparation

For evaluation of morphological aspects and measurement of β-cell mass, 26 pancreases were included in this study, removed from the following groups of mice: controls (n = 6); STZ-NA untreated diabetics (n = 6); 7.5 mg/kg IAC-treated (n = 4); 15 mg/kg IAC-treated (n = 5); 30 mg/kg IAC-treated (n = 5) diabetics. Each pancreas was cleared of fat and lymph nodes and weighed. A suitable fragment taken from the pancreatic tail was fixed in 10% buffered formalin and processed using the standard procedure to obtain a paraffin-embedded tissue block.

Immunohistochemical staining

Paraffin sections (2-μm thickness) were mounted on treated slides (two to three sections per slide) and dried in oven at 56°C for 20 min. After progressive hydration, the sections were incubated with a guinea pig anti-insulin polyclonal antibody (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA, USA), and immunoreactivity was visualised as a brown cytoplasmic staining by the kit Histomouse (Zymed Laboratories) containing diaminobenzidine chromogen. Negative controls were incubated in phosphate-buffered saline instead of primary antibody. Finally, the nuclei were stained in blue by haematoxylin, and the sections were submitted to morphometric analysis.

Morphometric analysis

Morphometric analysis was performed by a BX-51 Olympus microscope connected to a computer by a color CCD camera. The analySISB software (Olympus) was used to acquire images at different magnifications. In this way, we were able to obtain measurements in micrometre by the inside calibrator, and data were normalised per surface unit (square millimetre). The colorimetric property of the system was able to recognise and quantify the total section area (blue color + brown color), the total islet surface after selection of the perimeter of each islet present in the specimen and the insulin-positive area (brown color). The set-up of brown and blue colors was done using the staining of the corresponding control group. The average β-cell area measured in each pancreas specimen was used to calculate β-cell mass by multiplying it by the weight of the corresponding pancreas. In addition, the islet number was determined on each section by the computerised program and expressed per surface unit (square millimetre).

Electron microscopy

Pancreatic samples were fixed with 2.5% (vol./vol.) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mmol/l phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 2 h at 4°C, and then postfixed in 1% (vol./vol.) phosphate-buffered osmium tetroxide for 30 min at 4°C. Samples were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, transferred to propylene oxide and embedded in PolyBed 812 (Polysciences Inc.). Ultrathin sections (60–80 nm thick) were cut with a diamond knife, placed on copper grids (200 mesh), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with a Zeiss 902 electron microscope. Morphometric analyses were performed as previously described (Marchetti et al. 2004). Micrographs, obtained at ×10,000, were analysed by overlay with a graticule (11 × 11 cm) composed of 169 points. For the study of beta granules and mitochondria, volume density was calculated according to the formula: volume density = P i/P t, where P i is the number of points within the subcellular component and P t is the total number of points, and expressed as ml/100 ml tissue (ml%). Three to four islets per pancreas were studied, and 20–25 β cells per islet were analysed in non-diabetic controls (n = 3), untreated diabetic (n = 4) and 30 mg/kg IAC-treated diabetic mice (n = 4).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A p < 0.05, at least, was considered as significant.

Results

Time course of glycaemic levels

As shown in Fig. 2, 3-h fasted STZ-NA mice showed high blood glucose levels (about 170–180 mg/dl), which remained stable during the experimental period in untreated animals. These glycaemic levels are consistent with previous results obtained by our group and others in this diabetic model (Novelli et al. 2007; Tahara et al. 2008). IAC was administered at various doses (7.5, 15 or 30 mg/kg b.w./day) in diabetic mice and also in a group of non-diabetic controls at 30 mg/kg b.w. In diabetic mice, both IAC doses of 15 and 30 mg/kg significantly decreased plasma glucose levels after 2–3 weeks of treatment, showing similar effectiveness. The lowest IAC dose used (7.5 mg/kg b.w.) was only transiently effective and was finally unable to significantly reduce hyperglycemia in diabetic mice. No significant change in glycaemic values was induced by IAC treatment in non-diabetic controls (not shown). After 7 weeks of treatment, IAC administration was discontinued, and glycaemia was periodically monitored for additional 8 weeks. Interestingly, the correction of hyperglycaemia achieved with the IAC doses of 15 or 30 mg/kg b.w. persisted after the suspension of the drug until the end of the experiment.

Time course of glycaemic values in 3-h fasted control and diabetic mice during IAC treatment and after its discontinuation. Mean ± SEM of 10–12 mice for each group. C healthy controls, D STZ-NA diabetic mice without pharmacological treatment, D + IAC 7.5 diabetic mice treated with IAC 7.5 mg/kg b.w./day, D + IAC 15 diabetic mice treated with IAC 15 mg/kg b.w./day; D + IAC 30 diabetic mice treated with IAC 30 mg/kg b.w./day. Arrows indicate starting (+) and discontinuation (−) of IAC treatment. Statistical analysis (ANOVA) revealed significant differences between C and D; C and D + IAC 7.5, 15 and 30; D and D + IAC 15 and 30 (post hoc Tukey test)

Plasma insulin and nitrotyrosine levels

Plasma insulin levels, as measured 5 weeks after IAC treatment, were significantly (p < 0.05) decreased in untreated and 7.5 mg/kg IAC-treated diabetic mice with respect to controls and were improved in 15 and 30 mg/kg IAC-treated animals [controls (C): 0.98 ± 0.11 ng/ml; diabetics (D): 0.60 ± 0.07 ng/ml; D + 7.5 mg/kg IAC: 0.60 ± 0.08 ng/ml; D + 15 mg/kg IAC: 0.85 ± 0.09 ng/ml, NS vs. C or D; D + 30 mg/kg IAC: 0.92 ± 0.04 ng/ml, NS vs. C, p < 0.05 vs. D; n = 5–6 for each group].

We also measured plasma nitrotyrosine levels, which are considered a valuable index of overall oxidative stress (Ceriello et al. 2001), in untreated and treated diabetic mice 5 weeks after IAC treatment. Confirming previous results, we found that plasma nitrotyrosine levels, significantly (p < 0.05) increased in untreated and 7.5 mg/kg IAC-treated diabetic mice with respect to controls, were partially restored during the antioxidant treatment at the highest doses [controls (C): 0.68 ± 0.09 µg/ml; diabetics (D): 1.22 ± 0.10 μg/ml; D + 7.5 mg/kg IAC: 1.17 ± 0.07 μg/ml; D + 15 mg/kg IAC: 0.97 ± 0.06 µg/ml, NS vs. C or D; D + 30 mg/kg IAC: 0.98 ± 0.07 µg/ml, NS vs. C or D; n = 5–6 for each group).

Glucose tolerance test

An intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test, performed in STZ-NA mice 6 weeks after IAC treatment, showed that the severe glucose intolerance observed in diabetic animals was partially and similarly improved in the diabetic groups treated with IAC 15 and 30 mg/kg b.w. but not in the group treated with 7.5 mg/kg b.w. (Fig. 3a). In IAC-treated mice, the 15-min post-loading plasma insulin peak remained much lower than in healthy controls but not as low as in the untreated diabetic group (Fig. 3b). No significant alteration of insulin sensitivity was observed in any experimental group during i.p. insulin tolerance tests performed before and after discontinuation of IAC treatment (data not shown), consistently with previous results (Novelli et al. 2007). Thus, the partial improvement in glucose tolerance in mice treated with 15 and 30 mg/kg IAC should be ascribed to a slight/moderate enhancement in the insulin response to the glucose load, taking also into account that sampling at 15 min after the load might not correspond to the real peak of insulin secretion.

Glucose tolerance test in control and IAC-treated diabetic mice. Glycaemia and insulinaemia were determined during an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (glucose 1.5 g/kg) performed after 6 weeks of IAC treatment. Mean ± SEM of five to six mice for each group. Abbreviations are defined in Fig. 2. The upper inset shows the area under the curve (AUC) for the glycaemic values; the lower inset shows the percent increase of 15-min post-loading plasma insulin levels with respect to the corresponding basal value. *p < 0.01 vs. the corresponding controls; § p < 0.05 vs. the corresponding diabetics (post hoc Tukey test)

Quantitative immunohistochemical data

At the end of the experiment, immunohistochemical images of the pancreases from the various mice groups were submitted to quantitative analysis using an improved image analysis program, as detailed in “Materials and methods.” Representative images of pancreatic sections of each group, immunostained for insulin, are shown in Fig. 4. These high-magnification images (×400) provide evidence of the reduced insulin immunostaining in untreated diabetic islets with respect to control islets. A reduced cell density is apparent within the islets concomitantly with an increase of intercellular space. Conversely, in IAC-treated diabetic islets, density of cells and homogeneity of immunostaining are clearly improved as compared to diabetic islets and approach those of control islets. Morphometric analysis of images at low magnification (×40) revealed that untreated STZ-NA diabetic mice had a significant reduction in islet number (−70%), relative β-cell area (−76%) and β-cell mass (−76%) with respect to controls (Fig. 5a–c). IAC treatment significantly reversed the decrease in all these three parameters in a dose-related manner, although to a different extent. Indeed, the beneficial effect of IAC treatment was more attributable to preservation of β-cell area than of islet number. In particular, both 15 and 30 mg/kg IAC induced a clear-cut improvement with respect to untreated diabetic mice, and the highest dose nearly restored β-cell mass to the level of control mice.

Representative images of pancreas sections immunostained with an anti-insulin antibody. Pancreases were removed and processed at the end of the experiment, i.e. 8 weeks after the end of IAC treatment. Magnification ×400. Abbreviations are defined in Fig. 2

Islet number (a), relative β-cell area (b) and β-cell mass (c) in control and IAC-treated diabetic mice. These parameters were evaluated on images at low magnification (×40) obtained after insulin immunostaining, using an appropriate software, as described in “Materials and methods.” Mean ± SEM of four to six mice for each group. Abbreviations are defined in Fig. 2

Electron microscopy

Pancreas specimens from control and STZ-NA diabetic mice, untreated or treated with 30 mg/kg IAC, were also processed and analysed by electron microscopy to study the ultrastructural alterations of pancreatic islets (Fig. 6). In control mice, islets were quite large and characterised by many β cells with abundant mature granules. Nuclei were round and contained uncondensed chromatin. Mitochondria, Golgi apparatus, and rough endoplasmic reticulum had a normal appearance. No apoptotic cells or fibrosis could be detected. Conversely, in untreated STZ-NA diabetic mice, islets were usually small and contained β cells with reduced number of mature granules. Many β-cell nuclei appeared deformed with clusters of condensed chromatin behind the nuclear membrane. Mitochondria were numerous and often swollen, round in shape and with dispersed cristae. A few apoptotic β cells were also visible and some fibrosis occurred, as indicated by the presence of collagen fibers both around and within several islets (see Fig. 6, lower panels). Occasional deposits of amyloid fibrils were detectable. Interestingly, in IAC-treated diabetic mice, most of these changes did not occur, and islet ultrastructure was very similar to that of controls. In particular, β cells contained many mature granules; their nuclei were round with normal loose chromatin, and mitochondria appeared elongated with parallel cristae. Apoptosis and fibrosis were not observed. Several islets were located in close proximity to blood vessels.

Representative electron microscope images of pancreatic β cells from control (C), untreated (D) and 30 mg kg−1 day−1 IAC-treated (D + IAC) diabetic mice. Specimens from pancreases removed 8 weeks after the end of IAC treatment were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and processed for EM analysis, as detailed in “Materials and methods.” Upper panels (magnification, ×10,000): M with white arrows indicates mitochondria. Lower panels (magnification, ×16,000): evidence of an apoptotic β cell (asterisk) and collagen fibrils (black arrows) in diabetic mice, and a detail of a well granulated healthy β cell with a neighbor α cell (at the upper right corner) in IAC-treated animals

Morphometric analysis revealed that both number and volume density of mature granules were significantly reduced in β cells of STZ-NA diabetic mice with respect to controls and that IAC (30 mg/kg b.w.) treatment fully reversed these changes (Table 1). Moreover, in β cells of STZ-NA diabetic mice, both number and volume density of mitochondria were significantly increased with respect to controls, and IAC treatment restored both parameters to almost normal values (Table 1).

Discussion

It is increasingly being realized that T2D develops in insulin-resistant subjects when pancreatic β cells fail to secrete sufficient insulin to compensate for insulin resistance (Kahn 2003; Kasuga 2006). This failure ultimately leads to hyperglycaemia, which can in turn further impair β-cell secretory effectiveness and/or progressively reduce β-cell mass (Butler et al. 2003; Rhodes 2005; Robertson 2004; Ward et al. 1984). Among the various mechanisms potentially involved in hyperglycaemia-linked β-cell dysfunction and diabetes progression, chronic oxidative stress is recognized to play a major role (Brownlee 2003; Kaneto et al. 2005; Robertson 2004; Robertson et al. 2004). Oxidative stress refers to a persistent imbalance between excessive production of ROS and/or RNS and limited antioxidant defence. Pancreatic β cells are especially susceptible to this event, as they lack robust protection against toxicity of free radicals (Tiedge et al. 1997). Hyperglycemia can lead to increased radical generation in β-cells by a variety of mechanisms, including accelerated glycolytic flux and pyruvate feeding to the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Brownlee 2003), mitochondrial fragmentation (Men et al. 2009), enhanced rate of alternative metabolic pathways (e.g. those of polyols and hexosamine) (Robertson 2006), activation of NF-kB pathway and consequent induction of iNOS and production of inflammatory cytokines (Maedler et al. 2002), which in turn can increase intracellular ROS and NO generation (Eizirik and Mandrup-Poulsen 2001). This overproduction of ROS/RNS may have severe cytotoxic effects on β-cell structures through protein oxidation, membrane lipid peroxidation and DNA damage (Beckman and Koppenol 1996; Ceriello 2003). Furthermore, oxidative stress may impair the transcription of the insulin gene and other relevant β-cell genes by interfering with the transcriptional activity of the pancreatic and duodenal homeobox factor-1 PDX-1 (Kaneto et al. 2006). Thus, a pharmacological approach for treatment of diabetes based on the use of low molecular weight antioxidants able to exert a prolonged ROS/RNS scavenging activity, possibly at sites of radical production like mitochondria, appears highly advisable (Ceriello 2003; Maritim et al. 2003; Murphy and Smith 2007; Soule et al. 2007).

On the basis of a previous diabetes model with reduced β-cell mass established in rats using diabetogenic doses of STZ and partially protective doses of NA (Masiello et al. 1998), we and others have developed an analogous model in C56Bl/6J mice (Masiello et al. 2006; Matsuyama-Yokono et al. 2008; Nakamura et al. 2006). STZ-NA-treated mice develop a non-obese diabetic syndrome characterised by moderate and stable hyperglycaemia, hypoinsulinaemia, growth impairment, and approximately 75% reduction of pancreatic insulin stores. In this model, we have previously shown that the non-conventional radical scavenger IAC, a “palindromic” nitroxide compound in its reduced hydroxylamine form (see Fig. 1), synthesised in our laboratories, improves diabetic metabolic alterations by counteracting β-cell dysfunction associated with oxidative stress (Novelli et al. 2007). A major aim of the present research was to verify whether the beneficial effect of IAC administration could be protracted after suspension of the treatment. Our results confirm that IAC treatment (at doses of 15 or 30 mg/kg b.w., but not 7.5 mg/kg b.w.) was able to decrease hyperglycaemia and improve glucose tolerance, meanwhile partially reducing plasma nitrotyrosine levels, an overall index of oxidative stress, which was increased twofold in diabetic mice, similarly to what has been reported in type 2 diabetic patients (Ceriello et al. 2001, 2004). Very interestingly, the correction of hyperglycaemia still persisted in STZ-NA diabetic mice 8 weeks after IAC discontinuation. With regard to the mechanism of the long-term beneficial effect of IAC treatment, we hypothesised that this improvement could be dependent on preservation of β-cell mass. To directly test this hypothesis, in the present study, we have measured β-cell mass on the basis of an improved method of morphometric analysis of pancreatic sections immunostained for insulin. Such analysis revealed that untreated STZ-NA mice had a 70–80% reduction of islet number, relative β-cell area and β-cell mass with respect to controls and that a daily IAC treatment for 7 weeks prevented these changes in a dose-related manner, although administration of the compound was suspended for several weeks prior to analysis. To our knowledge, only another non-peptidyl antioxidant compound, N-acetyl-cysteine, when combined with vitamins C and E, was able to partially reduce basal hyperglycaemia and improve β-cell mass in a mouse model of T2D (Kaneto et al. 1999). Actually, effective scavengers of both ROS and NRS have also been reported to prevent diabetes development in NOD mice, a well-known model of autoimmune type 1 diabetes (Olcott et al. 2004) or other autoimmune diseases like experimental encephalomyelitis (Malfroy et al. 1997). Furthermore, such scavengers, including IAC itself, have been shown to decrease tissue damage in experimentally induced colitis in rats (Cuzzocrea et al. 2000; Vasina et al. 2009) or in post-ischemic brain in Mongolian gerbils (Canistro et al. 2010), thereby confirming their beneficial effects in several pathological situations in which inflammation- or reperfusion-derived oxidative stress is supposed to play a major role.

Our data support the hypothesis that the remarkable decrease in β-cell mass found in untreated diabetic mice at the end of the experimental period (i.e. 18 weeks after induction of diabetes) is not only dependent on the acute β-cell destruction induced by STZ but also on the further β-cell loss due to the oxidative stress-induced apoptosis associated with chronic hyperglycaemia (Kim et al. 2005; Maedler et al. 2002). It is this additional β-cell loss that is probably prevented by IAC treatment, resulting in better preservation of islet number and islet β-cell core, as shown by our immunohistochemical data, which would explain the long-term correction of hyperglycaemia even after discontinuation of the treatment. These results are consistent with the observation that in isolated human islets, IAC prevented FFA-induced oxidative stress as well as reduction of β-cell viability and increase in the pro-apoptotic BAX/BCL-2 ratio (D'Aleo et al. 2009). However, it should be noticed that despite the improvement in β-cell mass, IAC-treated diabetic animals do not achieve full normalisation of glycaemia and glucose tolerance, suggesting that rescued β cells still hold some functional defect.

The prevention of mitochondrial alterations in β cells of IAC-treated diabetic mice, as shown by ultrastructural morphometric analysis, appears of particular interest. It has been recently documented that both β-cell dysfunction and increased mitochondrial superoxide levels induced by prolonged glucose infusion in vivo are fully prevented by treatment with the superoxide dismutase mimetic TEMPOL (Tang et al. 2007), a nitroxide radical structurally related to IAC. Actually, it is likely that IAC would better accumulate into mitochondria and would exert a stronger antioxidant effect than TEMPOL, due to its better membrane permeability conferred by the long aliphatic chain connecting the two cyclic hydroxylamine moieties. Furthermore, the nitroxide derived from IAC interaction with radicals would be rapidly reconverted to hydroxylamine with regeneration of the scavenging activity (Valgimigli et al. 2001). At this regard, it is worthwhile to mention that a mitochondria-targeted form of TEMPOL (mito-TEMPOL) was recently shown to be selectively taken up by mitochondria and here reduced to mito-TEMPOL-H, i.e. to its hydroxylamine, by mitochondrial ubiquinol (Trnka et al. 2008). Interestingly, mito-TEMPOL-H holds a remarkable antioxidant activity and is more effective at preventing lipid peroxidation than TEMPOL itself (Trnka et al. 2009).

Besides their central role in the control of insulin secretion, mitochondria may also contribute to the regulation of β-cell mass. The available data suggest that increased apoptosis underlies the loss of β-cell mass in type 2 diabetic patients (Butler et al. 2003). Mitochondria might well play a major role in this process, as they are involved in the regulation of cell apoptosis by multiple mechanisms (Jeong and Seol 2008). It is presently recognised that mitochondria are characterised by a remarkable plasticity (mitochondrial network), as their number and morphology are highly regulated through mitochondrial fusion and fission processes in response to physiological requirements or pathological stimuli (Detmer and Chan 2007; Jeong and Seol 2008; Wikstrom et al. 2007). With regard to hyperglycaemia and related enhanced ROS production, evidence is being accumulating that mitochondrial fragmentation by fission occurs under these circumstances and may lead to apoptosis through cytocrome c release into the cytosol (Men et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2008). At present, very little information is available on the ultrastructural alterations of β-cell mitochondrial in diabetes, apart from the increase in mitochondrial volume density observed by Anello et al. (2005) in islets isolated from type 2 diabetic donors. In β cells of STZ-NA diabetic mice, as compared to controls, we observed a significant increase in not only volume density of mitochondria due to their altered shape and swelling but also their number, likely as a consequence of increased fission events (Chan 2007). Interestingly, both alterations were corrected by IAC treatment, consistently with the possibility that this compound can indeed prevent mitochondrial fragmentation and rescue β cells from apoptotic outcome. Of course, further studies are needed to directly assess the influence of IAC on the molecular factors involved in mitochondrial dynamics and remodeling (Kuznetsov et al. 2009).

In conclusion, our study confirms that the radical scavenger IAC improves metabolic alterations in STZ-NA diabetic mice and shows that this improvement persists for a long time after discontinuation of IAC treatment, likely due to partial correction of β-cell dysfunction and prevention of β-cell loss induced by hyperglycaemia-linked oxidative stress. Furthermore, our ultrastructural data suggest that mitochondria could be a major site of the protective action of IAC in pancreatic β cells. Altogether, these findings reinforce the notion that antioxidant agents such as IAC may have a relevant therapeutic potential in diabetes.

References

Anello M, Lupi R, Spampinato D, Piro S, Masini M, Boggi U, Del Prato S, Rabuazzo AM, Purrello F, Marchetti P (2005) Functional and morphological alterations of mitochondria in pancreatic beta cells from type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 48:282–289

Beckman JS, Koppenol WH (1996) Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol 271:C1424–C1437

Brownlee M (2003) A radical explanation for glucose-induced β cell dysfunction. J Clin Invest 112:1788–1790

Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC (2003) Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 52:102–110

Canistro D, Affatato A, Soleti A, Mollace V, Muscoli C, Sculco F, Sacco I, Visalli V, Bonamassa B, Martano M, Iannone M, Sapone A, Paolini M (2010) The novel radical scavenger IAC is effective in preventing and protecting against post-ischemic brain damage in Mongolian gerbils. J Neurol Sci 290:90–95

Ceriello A (2003) New insights on oxidative stress and diabetic complications may lead to a “causal” antioxidant therapy. Diab Care 26:1589–1596

Ceriello A, Mercuri F, Quagliaro L, Assaloni R, Motz E, Tonutti L, Taboga C (2001) Detection of nitrotyrosine in the diabetic plasma: evidence of oxidative stress. Diabetologia 144:834–838

Ceriello A, Assaloni R, Da Ros R, Maier A, Quagliaro L, Piconi L, Esposito K, Giugliano D (2004) Effect of irbesartan on nitrotyrosine generation in non-hypertensive diabetic patients. Diabetologia 47:1535–1540

Chan DC (2007) Mitochondrial dynamics in disease. N Engl J Med 356:1707–1709

Cuzzocrea S, McDonald MC, Mazzon E, Dugo L, Lepore V, Fonti MT, Ciccolo A, Terranova ML, Caputi P, Thiemermann C (2000) Tempol, a membrane-permeable radical scavenger, reduces dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. Eur J Pharmacol 406:127–137

D'Aleo V, Del Guerra S, Martano M, Bonamassa B, Canistro D, Soleti A, Valgimigli L, Paolini M, Filipponi F, Boggi U, Del Prato S, Lupi R (2009) The non-peptidyl low molecular weight radical scavenger IAC protects human pancreatic islets from lipotoxicity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 309:63–66

Detmer SA, Chan DC (2007) Functions and dysfunctions of mitochondrial dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:870–879

Eizirik DL, Mandrup-Poulsen T (2001) A choice of death. The signal-transduction of immune-mediated beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetologia 44:2115–2133

Herbert V, Lau KS, Gottlieb CW, Bleicher SJ (1965) Coated charcoal immunoassay of insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 25:1375–1384

Jeong S-Y, Seol D-W (2008) The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. BMB Rep 41:11–22

Kahn SE (2001) The importance of β-cell failure in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:4047–4058

Kahn SE (2003) The relative contributions of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction to the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 46:3–19

Kaneto H, Fujii J, Myint T, Miyazawa N, Islam KN, Kawasaki Y, Suzuki K, Nakamura M, Tatsumi H, Yamasaki Y, Taniguchi M (1996) Reducing sugars trigger oxidative modification and apoptosis in pancreatic β-cells by provoking oxidative stress through the glycation reaction. Biochem J 320:855–863

Kaneto H, Kajimoto Y, Miyagawa J, Matsuoka T, Fujitani Y, Umayahara Y, Hanafusa T, Matsuzawa Y, Yamasaki Y, Hori M (1999) Beneficial effects of antioxidants in diabetes. Possible protection of pancreatic beta-cells against glucose toxicity. Diabetes 48:2398–2406

Kaneto H, Xu G, Song KH, Suzuma K, Bonner-Weir S, Sharma A, Weir GC (2001) Activation of the hexosamine pathway leads to deterioration of pancreatic β-cell function by provoking oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 276:31099–31104

Kaneto H, Kawamori D, Matsuoka T, Kajimoto Y, Yamasaki Y (2005) Oxidative stress and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Am J Ther 12:529–533

Kaneto H, Nakatani Y, Kawamori D, Miyatsuka T, Matsuoka TA, Matsuhisa M, Yamasaki Y (2006) Role of oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase in pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 38:782–793

Kasuga M (2006) Insulin resistance and pancreatic beta cell failure. J Clin Invest 116:1756–1760

Kim WH, Lee JW, Suh YH, Hong SH, Choi JS, Lim JH, Song JH, Gao B, Jung MH (2005) Exposure to chronic high glucose induces beta-cell apoptosis through decreased interaction of glucokinase with mitochondria. Diabetes 54:2602–2611

Kuznetsov AV, Hermann M, Saks V, Hengster P, Margreiter R (2009) The cell-type specificity of mitochondrial dynamics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41:1928–1939

Lowell BB, Shulman GI (2005) Mitochondrial dysfunction and type 2 diabetes. Science 307:384–387

Maedler K, Sergeev P, Ris F, Oberholzer J, Joller-Jemelka HI, Spinas GA, Kaiser N, Halban PA, Donath MY (2002) Glucose-induced beta cell production of IL-1beta contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J Clin Invest 110:851–860

Malfroy B, Doctrow SR, Orr PL, Tocco G, Fedoseyeva EV, Benichou G (1997) Prevention and suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis by EUK-8, a synthetic catalytic scavenger of oxygen-reactive metabolites. Cell Immunol 177:62–68

Marchetti P, Del Guerra S, Marselli L, Lupi R, Masini M, Pollera M, Bugliani M, Boggi U, Vistoli F, Mosca F, Del Prato S (2004) Pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic patients have functional defects and increased apoptosis that are ameliorated by metformin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:5535–5541

Maritim AC, Sanders RA, Watkins JB 3rd (2003) Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: a review. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 17:24–38

Masiello P, Broca C, Gross R, Roye M, Manteghetti M, Hillaire-Buys D, Novelli M, Ribes G (1998) Experimental NIDDM: development of a new model in adult rats administered streptozotocin and nicotinamide. Diabetes 47:224–229

Masiello P, D’Aleo V, Lupi R, Paolini M, Soleti A, Marchetti P, Novelli M (2006) Characterization of a non-genetic non-obese model of type 2 diabetes in mice given streptozotocin and nicotinamide and its application for testing the antidiabetic properties of a new antioxidant compound. Diabetologia 49(suppl 1):381

Matsuyama-Yokono A, Tahara A, Nakano R, Someya Y, Nagase I, Hayakawa M, Shibasaki M (2008) ASP8497 is a novel selective and competitive dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor with antihyperglycemic activity. Biochem Pharmacol 76:98–107

Men X, Wang H, Li M, Cai H, Xu S, Zhang W, Xu Y, Ye L, Yang W, Wollheim CB, Lou J (2009) Dynamin-related protein 1 mediates high glucose induced pancreatic beta cell apoptosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41:879–890

Murphy MP, Smith RA (2007) Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria by conjugation to lipophilic cations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:629–656

Nakamura T, Terajima T, Ogata T, Ueno K, Hashimoto N, Ono K, Yano S (2006) Establishment and pathophysiological characterization of type 2 diabetic mouse model produced by streptozotocin and nicotinamide. Biol Pharm Bull 29:1167–1174

Novelli M, D’Aleo V, Lupi R, Paolini M, Soleti A, Marchetti P, Masiello P (2007) Reduction of oxidative stress by a new low-molecular-weight antioxidant improves metabolic alterations in nonobese mouse diabetic model. Pancreas 35:e10–e17

Olcott AP, Tocco G, Tian J, Zekzer D, Fukuto J, Ignarro L, Kaufman DL (2004) A salen-manganese catalytic free radical scavenger inhibits type 1 diabetes development and islet allograft rejection. Diabetes 53:2574–2580

Prentki M, Nolan CJ (2006) Islet β cell failure in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 116:1802–1812

Rhodes CJ (2005) Type 2 diabetes—a matter of beta-cell life and death? Science 307:380–384

Robertson RP (2004) Chronic oxidative stress as a central mechanism for glucose toxicity in pancreatic islet beta cells in diabetes. J Biol Chem 279:42351–42354

Robertson RP (2006) Oxidative stress and impaired insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes. Curr Opin Pharmacol 6:615–619

Robertson RP, Harmon J, Tran PO, Poitout V (2004) Beta-cell glucose toxicity, lipotoxicity, and chronic oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 53(Suppl 1):S119–S124

Soule BP, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Simone NL, Cook JA, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB (2007) The chemistry and biology of nitroxide compounds. Free Radic Biol Med 42:1632–1650

Tahara A, Matsuyama-Yokono A, Nakano R, Someya Y, Shibasaki M (2008) Effects of antidiabetic drugs on glucose tolerance in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced mildly diabetic and streptozotocin-induced severely diabetic mice. Horm Metab Res 40:880–886

Tahara A, Matsuyama-Yokono A, Nakano R, Someya Y, Hayakawa M, Shibasaki M (2009) Effects of the combination of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor ASP8497 and antidiabetic drugs in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced mildly diabetic mice. Eur J Pharmacol 605:170–176

Tang C, Han P, Oprescu AI, Lee SC, Gyulkhandanyan AV, Chan GN, Wheeler MB, Giacca A (2007) Evidence for a role of superoxide generation in glucose-induced beta-cell dysfunction in vivo. Diabetes 56:2722–2731

Tiedge M, Lortz S, Drinkgern J, Lenzen S (1997) Relation between antioxidant enzyme gene expression and antioxidant defense status of insulin-producing cells. Diabetes 46:1733–1742

Trnka J, Blaikie FH, Smith RA, Murphy MP (2008) A mitochondria-targeted nitroxide is reduced to its hydroxylamine by ubiquinol in mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med 44:1406–1419

Trnka J, Blaikie FH, Logan A, Smith RA, Murphy MP (2009) Antioxidant properties of MitoTEMPOL and its hydroxylamine. Free Radic Res 43:4–12

Valgimigli L, Pedulli GF, Paolini M (2001) Measurement of oxidative stress by EPR radical-probe technique. Free Radic Biol Med 31:708–716

Vasina V, Broccoli M, Ursino MG, Fio’ Bellot S, Soleti A, Paolini M, De Ponti F (2009) Effects of the non-peptidyl low molecular weight radical scavenger IAC in DNBS-induced colitis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 614:137–145

Ward WK, Bolgiano DC, McKnight B, Halter JB, Porte D Jr (1984) Diminished B cell secretory capacity in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 74:1318–1328

Wikstrom JD, Katzman SM, Mohamed H, Twig G, Graf SA, Heart E, Molina AJ, Corkey BE, de Vargas LM, Danial NN, Collins S, Shirihai OS (2007) Beta-cell mitochondria exhibit membrane potential heterogeneity that can be altered by stimulatory or toxic fuel levels. Diabetes 56:2569–2578

Yu T, Sheu S-S, Robotham JL, Yoon Y (2008) Mitochondrial fission mediates high glucose-induced cell death through elevated production of reactive oxygen species. Cardiovasc Res 79:341–351

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants of the University of Pisa and University of Bologna.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Novelli, M., Bonamassa, B., Masini, M. et al. Persistent correction of hyperglycemia in streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetic mice by a non-conventional radical scavenger. Naunyn-Schmied Arch Pharmacol 382, 127–137 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-010-0524-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-010-0524-7