Abstract

Fragility fracture audit is key to understanding fragility fracture management, identifying areas for its improvement and measuring the impact of clinical initiatives and service change. Hip fracture can be considered a marker for fragility fractures, and hip fracture audits indirectly show strengths and weaknesses of fragility fracture care overall. Notably, where effective hip fracture care exists, this has a favourable impact on the care of other fragility fractures. Early established audits, clinically led, have used clinical standards and feedback on compliance with them to improve care and outcomes. Although data collection, analysis and feedback require investment, the cost per case amounts to only a very small fraction of the cost of care per case. More recently established audits have also proved effective, and increasingly international collaboration on hip fracture audit is now emerging: an important development in view of demographic projections reflecting first-generation mass ageing in a number of large nations. Parallel developments such as fracture liaison services promote both primary and secondary fracture prevention. In future, automated data collection using reliable electronic health records may facilitate audit and international collaboration and enabling instructive comparisons and, eventually, multinational hip fracture-related clinical and epidemiological research.

This chapter is a component of Part 5: Cross-cutting issues.

For an explanation of the grouping of chapters in this book, please see Chapter 1: “The multidisciplinary approach to fragility fractures around the world—an overview”.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

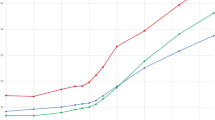

Hip fracture is a common, serious and costly injury that presents acutely, requires surgery, carries both residual disability and a high mortality, and is much easier to identify and register than other osteoporotic fractures [1, 2]. It is therefore an ideal index condition for clinical audit and also a tracer condition for the broader fragility fracture pandemic now challenging healthcare systems worldwide. Even though age-adjusted incidence of hip fractures is falling in some regions, population incidence is increasing due to rising life expectancy worldwide, and is estimated to grow from 1.66 million in 1990 to 6.26 million in 2050, with steep increases throughout Asia and Latin America [3, 4], potentially placing the healthcare systems of these regions under considerable stress. Good management of hip fracture demands integration of excellent nursing, surgical, anaesthetic, medical and rehabilitative care. Furthermore, there is a relatively strong evidence base on key quality standards for aspects of care in all phases of management, many of which have been implemented by clinical teams working with hospital management authorities to improve cost-effectiveness and quality of care [5]; some of these indicators have been used for international comparisons of care across different healthcare systems [6]. Quality care of this tracer condition benefits the care of other types of fragility fracture, via good orthogeriatric care, and access to rehabilitation units and fracture liaison services [7]. Ideally, sustained audit with continuous feedback can deliver continuous quality improvement by allowing organisations first to ascertain the nature of the care they provide, including its deficits, then to use data to prompt clinical and service structure improvements and then to assess the impact of these (Fig. 19.1) [8].

2 Hip Fracture Audit

Orthopaedic audit as we know it was born in Sweden in the 1970s and began with elective surgery in the form of the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register and Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register [9, 10]. The nature of the Swedish healthcare system—providing free care at the point of delivery in publicly funded hospitals, and patient traceability since every citizen has a national personal identification number—made implementation of a national registry relatively easy. More national registries developed in the following decades, among them the Swedish Hip Fracture Registry or Rikshöft, initiated in Lund in 1988 by Professor Karl-Göran Thorngren [11]. Rikshöft differed from previously existing orthopaedic registries in that, besides data regarding fracture type and treatment, it also collected data on patients’ functional level and residential status.

This was followed by the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit (SHFA) [12], based on Rikshöft and initiated in 1993, and the Standardised Audit of Hip Fracture in Europe (SAHFE) initiative (1994–1998) [13], with participation from 15 European nations, with the goals of (1) devising a standard data set for documentation of treatment and outcome for hip fractures; (2) piloting the use of such a dataset within Europe; (3) promoting Europe-wide comparisons of demographic features, surgical techniques and rehabilitation methods; (4) determining the practicalities of collecting and disseminating this information on a Europe-wide basis; (5) evaluating the effectiveness and differences of hip fracture care throughout Europe and (6) facilitating the dissemination of the best practice of hip fracture surgery and rehabilitation throughout Europe.

As a result of these initiatives, several other national audits emerged in Europe in the following decade, the most important of which was the National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) which covered England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and is currently the registry with the highest number of cases collected [14]. National hip fracture audits were however mainly limited to Scandinavia, Great Britain and Ireland. The Fragility Fracture Network (FFN), a global not-for-profit organisation founded in 2011, sets out to promote the wider establishment of hip fracture audit—as a way to assess the effectiveness of national fragility fracture networks—and latterly has directed its efforts towards creating regional and national alliances.

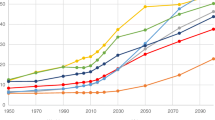

Its Hip Fracture Audit Special Interest Group proposed a Minimum Common Data set (Fig. 19.2)—a concise, practical and cost-effective data set for audit start-ups working within resource constraints—that also served to facilitate large-scale international comparisons of case-mix, care and mortality outcomes [15]. It should be considered a minimum recommended data set, to which other variables can be added at the discretion of each local, regional or national audit. The FFN Hip Fracture Audit Database Pilot Phase included hospitals from Lübeck and Stuttgart, Germany; Celje, Slovenia; Msida, Malta; and Barcelona, Spain; the latter two hospitals discontinuing their participation due to organisational constraints, mainly the heavy reliance on the enthusiasm of individual clinicians. In spite of these issues, the Pilot Phase detected large differences in case-mix, care provided and process measures (Fig. 19.3) and usefully highlighted some of the problems encountered by nascent hip fracture audits.

Results of the FFN Hip Fracture Audit Database Pilot Phase (Data extracted from: Bunning T, Currie, CT. Final Report of the Hip Fracture Audit Database (HFAD) Pilot Phase. Crown Informatics Limited; 2017 [15]). (a) Fracture type; (b) operation performed; (c) time to surgery and (d) discharge destination

Several new hip fracture audits have been initiated in the past decade, many in regions far from traditional Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian influence. While not a national-level system, Kaiser Permanente is the largest managed health care organisation of the United States with over 11 million insured and created a hip fracture registry in 2009 as part of its National Implant Registries to track implants in patients insured by the company. Its 2017 report includes over 44.000 patients. Other national audits have been created in Norway [16], Denmark [17], Ireland [18], Australia and New Zealand [19], Germany [20], the Netherlands [21, 22], Italy [23], Spain [24] and France (see Box 19.1). There are, however, marked differences across the health care economies in which they function and in how they are organised and financed. Such factors account for considerable differences in their growth and continuity; their differing ascertainment and follow-up rates and the wide variability documented in Table 19.1. A large majority of the countries with established audits have publicly funded healthcare systems, which seem to offer a more favourable environment for clinical audit and comparison among hospitals.

Box 19.1List of National Hip Fracture Registries and Their Web Addresses, When Available. Audits Marked with Asterisk Are Currently in Their Pilot Phases

-

Sweden (Rikshöft)—https://rikshoft.se/

-

Scotland, Scottish Hip Fracture Registry (SHFA)—https://www.shfa.scot.nhs.uk

-

Demnark, Dansk Tværfagligt Register for Hoftenære Lårbensbrud (DTRHL)—https://www.rkkp.dk/om-rkkp/de-kliniske-kvalitetsdatabaser/hoftenaere-laerbensbrud/

-

Finland (PERFECT)—http://thl.fi/fi/tutkimus-ja-kehittaminen/tutkimukset-ja-hankkeet/perfect/osahankkeet/lonkkamurtuma/perusraportit

-

Norway, Nasjonalt Hoftebruddregister (NHR)—http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/

-

England, Wales & Northern Ireland (National Hip Fracture Database, NHFD)—https://nhfd.co.uk/

-

United States (Kaiser Permanente Hip Fracture Registry)—https://national-implantregistries.kaiserpermanente.org/

-

Ireland (Irish Hip Fracture Database, IHFD)—https://www.noca.ie/audits/irish-hip-fracture-database

-

Australia, New Zealand; Australian and New Zealand National Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR)—https://anzhfr.org/

-

Germany, Alterstraumaregister (DGU-ATR)—http://www.alterstraumaregister-dgu.de

-

Netherlands, Dutch Hip Fracture Audit (DHFA)—https://dica.nl/dhfa/home

-

Italy, Gruppo Italiano di Ortogeriatria (GIOG)*—https://www.sigg.it/gruppo-di-studio/gruppo-italiano-di-ortogeriatria-giog-sigg-aip-sigot/

-

Spain, Registro Nacional de Fracturas de Cadera (RNFC)—http://rnfc.es/

-

France, Groupe d’étude en traumatologie ostéo-articulaire (GETRAUM)*—http://www.getraum.fr/

Other start-ups have been reported in the last decade, most notably Hong Kong [32, 33], Malaysia [34] Lebanon [35] and Iran [36, 37], but detailed continuing information about their survival and impact is, to our knowledge, not in the public domain. Other countries such as France, Mexico [38] and Japan [15] are in the pilot phase of national hip fracture audit development. Two are of special interest on account of their size and demography. Japan has the highest life expectancy worldwide [39], and Spain has the highest life expectancy in Europe [6] and is predicted to overtake Japan by 2040, with both countries forecast to exceed 85 years of life expectancy by 2040 [40].

Regional initiatives including those from British Columbia [41] and the Baltic Region [42] should also be mentioned. Several other countries are using large clinical databases to analyse hip fracture management. In the United States, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) collects retrospective data from patients admitted using the ICD-9 codes. Other examples include the American College of Surgeons prospective National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) and the Trauma Quality Improvement Project (TQIP) using data obtained directly from the medical records by trained surgeons. Though not specific to hip fracture, they include much hip fracture data and are a source of research studies [43, 44] due to their large numbers of patients and available data. Other studies have, however, shown significant variation in data inclusion and completeness, which could jeopardise the validity of conclusions reached in evaluating the care provided [45, 46].

Other countries with quality analyses based on general clinical or national databases are Germany, with its impressive external quality assurance programme for orthogeriatric care [47, 48]; Canada with the Canadian Institute for Health Information [49, 50] and South Korea using data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service [51, 52].

3 Obstacles to Hip Fracture Audit and International Comparison

Several authors have recently compared national hip fracture audits, showing important differences in inclusion criteria, follow-up, variables included and coverage [22, 24, 53, 54]. For example, the minimum age at which hip fracture patients are included ranges from all adults in the Netherlands to patients 75 years old or older in Spain. Follow-up ranges from 30 days for many registries such as Scotland, Ireland and Spain to 120 days for Sweden, Norway, the UK, Germany and Australia and New Zealand. Others, such as Denmark and Italy, have several cut-off points for follow-up. Data collected on function also vary between registries: while some collect the ability to walk assisted or unassisted indoors or outdoors, others use scores such as the cumulative ambulation score (e.g. Denmark) and a new mobility score (e.g. in Ireland) [18]. Functional and residential status data are more difficult to collect than discrete hard data such as re-operation rates or mortality, but it can be argued that the former is just as, if not more, relevant for the patient than the latter [55]. Very few registries include data regarding quality of life, with Germany and the NHFD collecting EQ-5D data.

However, collection of data after discharge can be more resource intensive—and loss of follow-up can pose a threat to the integrity of an overly ambitious audit data set. Some registries, such as the Kaiser Permanente and Norwegian hip fracture registry, are incorporated into larger administrative databases analysing joint implants, but largely lack clinical follow-up. For these reasons, we believe that an international consensus defining a limited but robust core data set—to be included by all interested audits, whatever other data they collect, and judiciously adapted in the light of emerging evidence—is paramount, and accordingly is proposed by the FFN. In terms of coverage, the UK NHFD and the Danish audit capture practically all occurring hip fractures. Other still nascent audits such as those in Australia, New Zealand, Spain and Holland include between one-quarter and one-half of estimated yearly hip fracture numbers. Since hospitals already interested in improving hip fracture care and providing orthogeriatric care are more likely to be early adopters of a voluntary hip fracture audit, concerns arise for possible inclusion bias. Fracture care and outcomes in such settings are better than average, so the overall reported quality of care may deteriorate as later adopters join the audit.

Some audits require individual patient consent to inclusion, as is the case in Spain [24], Italy [23] and Norway [16, 56]. The need for informed individual patient consent to store routinely collected healthcare data is debatable. In the European Union, a new framework known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [57] came into force across the EU on 25 May 2018. The GDPR requires that processing of personal data is fair, lawful and transparent. Currently there is nothing in the legislation that prevents clinical audit being carried out locally or nationally. Health data are defined under the GDPR via a special category of personal data and can be processed in situations where it is necessary to do so for reasons of public health. Regarding the conditions for lawful processing of personal data (Article 6), clinical audit fulfils GDPR Articles 6(1)(c), “processing necessary for performance of contract” with the data subject, or Article 6(1)(e), “processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller”, and Article 6(1)(f), “processing is necessary for the purposes of legitimate interests”. With reference to conditions for processing special categories of personal data (Article 9), “processing is necessary for the purpose of preventative… medicine… the provision of health or social care or treatment or the management of health or social care systems and services…” (Article 9(2)(h)) and “processing is necessary for reasons of public interest in the area of public health, such as… ensuring high standards of quality and safety of health care…” (Article 9(2)(h)). The Irish National Office for Clinical Audit has recently analysed the relevance of the GDPR and patient consent for national clinical audit [58], and has concluded that (1) for national clinical audit, all patients meeting the criteria of the audit should be included, so that a full national picture can be collected; (2) consent would not be appropriate because the patient could decline to give their consent or subsequently withdraw their consent at any time. Both of these individual rights would prevent collection of a full national picture; (3) national clinical audit should not rely on consent as the lawful basis but should instead justify such audit on the public health lawful basis as applicable e.g. Articles 6(1)(e), 6(1)(f). Finally, (4) the collection of data, validation of data, review of outliers for national clinical audit does not require consent and (5) patients should, however, be informed that their data may be used as part of a national clinical audit e.g. through information leaflets.

Patients with cognitive impairment—occurring in up to 30% of patients with hip fracture—are excluded when consent is required, which greatly limits the practical utility of audit findings. Validity of consent from a patient’s family varies across jurisdictions, may be time-consuming and may thus increase preoperative delay. In some jurisdictions, a supplementary explanation about audit and its value may be provided during consent to surgery—with opt-out where feelings are strong. However, the evidential value of findings from an audit that includes all, or almost all, cases is such that all reasonable and sympathetic measures available should endeavour to achieve universal coverage.

4 Hip Fracture Audit and the Improvement of Care

Since improving care is the main purpose of audit, the acquisition, ownership, analysis and use of data are of vital importance. Audit data can be collected by individual units and used by clinicians and management for internal quality reporting and continuous improvement or for external monitoring by health authorities and national governments for purposes of accountability for sanction or reward [59]. Data can be collected in an automated fashion through hospital administrative databases and coding by non-clinical staff, but the reliability of these data is relatively low, with median values for diagnostic accuracy around 80% [60, 61]. Electronic health records may be expected to improve the reliability of this data, again with the above proviso.

It should be noted that using outcome data for sanction or reward can lead to perverse incentives—such as targeting inclusion and treatment to the patients with the best prognosis or assigning patients to more serious risk categories. To avoid such “gaming”, responsible clinician involvement to defend data reliability is vital. Where possible, data linkage with centralised national statistics, using patient identifiers such as national personal identification numbers, is of great value in tracking both inclusion rates and survival. Data protection laws vary between jurisdictions, and may complicate achieving data linkage, but uploading to national level may be facilitated by a process of pseudo-anonymisation of bulked annual data.

Clinical outcomes such as mortality and residential status depend on many factors not related to quality of care. A systematic review showed that, though significant, the correlation between the quality of clinical practice and hospital mortality was low [62]. Risk adjustment would account only for the variables that have been measured and these could have a different effect across groups. Other outcomes such as quality of life or change in residential status are also relevant, especially for patients and their families, while healthcare systems should also consider readmission and reoperation rates.

Measures of clinical process are, however, easier to collect and compare. These should be quality- and evidence-based, and the effort required to improve the processes analysed should be proportionate to the contingent gains; improvement should also not come at the expense of other variables not monitored. The combination of audit, guidelines and standards constitutes the basis of clinical governance for hip fracture care, and good hip fracture audit has been shown to improve process indicators such as reduction in surgical delay, as well as outcome indicators such as 30-day mortality, with some reports estimating over a 1000 lives saved by the NHFD since its inception in 2007 [63, 64].

Most hip fracture registries and their governing agencies have implemented national standards which address similar quality goals, such as geriatrician involvement, surgical delay, early mobilisation and prevention of new fractures [14, 19, 31, 65,66,67]. Some of these quality standards are summarised in Table 19.2. The NHS’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) defined quality standards for hip fracture care in 2012 and updated them in 2016 [69]. Building upon these, the British Orthopaedic Association, together with the British Geriatrics Society, the NHFD and FFN-UK have recently updated the “BOA Standard of Care (BOAST) for the older or frail orthopaedic trauma patient”, adding detail for fragility fracture patients beyond hip fracture [70].

In addition, the Best Practice Tariff (BPT), an individual patient-level payment made to hospitals when they deliver care which meets all of the quality standards in the audit, was introduced in England in 2010 and relied heavily on NHFD data [14]. Criteria were updated in 2017 to include delirium, nutrition and early physiotherapy. Achievement of BPT criteria has been shown to lead to improved survival following hip fracture, both in single-centre cohort studies [68] and when comparing results in England and Scotland, with over 1000 deaths avoided per year in England that could be attributed to these interventions [71]. The UK NHFD incorporates standards from all three criteria as benchmarks that are publicly available on their website, with BPT criteria achieved for 57.1% of all NHFD patients in 2017.

Quality standards are regularly updated and modified, and while initial standards focused mainly on acute care, they now incorporate achievement of rehabilitation and post-acute care goals and more. All registries studied include secondary fracture prevention among their quality standards [31, 65,66,67]. The Irish Hip Fracture Database has also implemented a BPT since 2018 and in the initial 12-month period there has been a significant improvement in data quality seen in the Irish Hip Fracture Care Standards and hospital governance arrangements [18]. The most notable improvement has been the development of an orthogeriatric service in almost every hospital.

Clinical audits must be sustained in order to maintain continuous improvement and benchmarking standards should be updated to close the quality improvement circle. Interruption of the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit showed a deterioration of process indicators such as time to theatre, which recovered when the audit was re-introduced 5 years later [72].

Finally, national registries have been the source for further research regarding hip fracture care both for comparison of local results with other international registries [46, 47, 66] and for studies adding on national registry data to address specific questions. An excellent example is the UK Anaesthesia Sprint Audit of Practice (ASAP-2) [73], a large NHFD-based prospective study including 11,085 cases. This highlighted the critical importance of maintaining intra-operative systolic normo-tension and identified the associated risks of higher dosages of subarachnoid local anaesthetic. Together with its predecessor ASAP-1 [74], this has transformed the evidence base for hip fracture anaesthesia, which had previously consisted of a number of small trials from one or two hospitals, which often excluded patients with cognitive impairment (typically c. 30%) and were thus of limited impact in terms of the care of the typical hip fracture casemix. Another Anaesthesia Sprint Audit of Practice, ASAP-3, aimed at studying the anaesthetic management of periprosthetic fractures, is set to commence in 2020.

Many published single-hospital NHFD reports have documented care quality improvements such as improved pain control, reductions in peri-operative medical and surgical complications, and more rapid recovery, and reduced length of stay, sometimes with substantial reductions in bed days. More recently, the World Hip Trauma Evaluation (WHiTE) initiative has been set up to measure outcome in a cohort of hip fracture patients within the framework of the NHFD [75]. Under individual patient consent or family agreement where appropriate, WHiTE has recruited over 20,000 patients with hip fracture and collected patient-reported outcome measurement in more than 80% of participants. Studies such as WHiTE provide reliable observational outcome data, but also act as a platform for virtual clinical trials which can assess single interventions such as new forms of surgery and also serves as a framework to assess innovations throughout the hip fracture journey of care from pre-hospital pain relief to community rehabilitation [76].

Though good evidence can be obtained from both registries and clinical trials, registry studies are not equivalent to formal clinical trials. In orthopaedic surgery, knowledge usually advances from individual case series of a new operative technique or care process to case–control studies and then randomised trials. However, even these trials usually show results under optimal conditions in academic or specialised centres, with a high risk for publication bias. National guidelines are usually based on systematic reviews of randomised investigations, while these are excellent in compensating for confounding factors, they present problems in addition to selection and publication bias. Clinical trials are cost-intensive and often limited to a short observation period. Ethical issues arise when studying controversies such as surgical delay or weight-bearing after hip fractures.

National registries, however, pose the advantage of covering all incident cases within a country, reflecting the breadth of experience and training across a whole healthcare system, rather than specialist academic centres. They therefore offer a truer picture of everyday practice and regional variability. Another advantage of national registries is their large case numbers, allowing for collection of data of uncommon patient features and adverse events, such as surgical delay of patients with double anticoagulation, or fat embolism syndrome. They also allow for analysis of patient-centred outcome variables such as patient quality of life, social living situation and functional capacity from a representative group of patients, though trials are more likely to collect good quality outcome data especially during follow-up, largely as a result of better funding.

Finally, continuous data collection allows for identification of time trends in hip fracture epidemiology and the effects of measures implemented by healthcare practitioners or healthcare systems. Interestingly, the BMJ recently pointed out that “observational research using Big Data can explore the effect of disease and care on many patients… at a low cost per question. Big Data are more representative of the ‘real world’ than Little Science trials that recruit a few patients from referral centres. Clinical trialists can often use Big Data to design more efficient and useful trials…” [77]. The implications of this for audit-based clinical research in hip fracture care appear to be clear—with Big Data abundantly available now and for the foreseeable future.

5 Audit of Other Fragility Fractures and Fracture Liaison Services (FLS)

While hip fracture audit is relatively established in many regions worldwide, other fragility fractures are audited much less commonly. This is in large part due to the difficulty of identifying cases that frequently do not require hospital admission; as a matter of fact, many vertebral fractures go clinically undetected [78, 79]. As noted above, nearly all hip fractures are diagnosed acutely, hospitalised and managed surgically, making them easier to identify and register. In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is leading a 2020 Sprint Audit to investigate vertebral fracture identification [80]. Sweden has developed a Fracture Registry including all types of fractures (fragility and non-fragility) starting in 2011, covering 80% of orthopaedic departments in 2018. It has to date collected more than 400,000 fracture cases, including patient-reported outcome measures [81, 82]. Many hip fracture registries already include non-hip femoral fractures or plan to do so: while the German registry includes periprosthetic fractures and peri-implant fractures, the NHFD and ANZHFR are planning to add distal femoral fractures, and several arthroplasty registries are performing sub-analyses of periprosthetic fractures. These, while they study intraoperative factors and issues related to prosthetic design, often lack data regarding patient outcomes [83,84,85].

Further audit research is now focussing on Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) databases, for example that in England under the RCP, as part of the same Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme (FFFAP) together with the NHFD [86], and in Canada, with 45 FLSs in 2018 [87]. Spain is currently piloting a fragility fracture and FLS audit, the REFRA-FLS-registry, with over a dozen hospitals participating [88]. The international development of FLS programs has previously been extensively studied in the book by Seibel and Mitchell [89]. These FLS registries, however, are more centred on secondary prevention than on acute multidisciplinary care and post-acute care and rehabilitation, and do not report on individual fracture types apart from ad hoc research studies such as the proposed RCP Vertebral Fracture Sprint Audit mentioned above. Finally, FLS registries appear to work best where they are integrated with other fracture registries (e.g. hip fracture audit), rather than when they are standalone registries.

6 Expansion of Hip Fracture Registries in Other Regions

Healthcare administrators have an interest in not only providing quality care but also cost-effective care. As the Blue Book published by the British Orthopaedic Association and British Geriatrics Society states, “Looking after hip fracture patients well is a lot cheaper than looking after them badly” [90]. In many countries, open comparisons between hospitals and regions have become commonplace; this however requires a certain cultural sensitivity. Press coverage of registry reports can be misleading, because journalists may not understand the importance of case-mix and random variation, since low-volume hospitals are more likely to show poorer figures due to statistically non-significant adverse events. Participation of healthcare professionals in the evaluation and communication of audit reports is important. Emphasis should be placed on overall changes in outcomes or process, rather than on outliers, and on targeting the particular strengths and weaknesses of organisations. Over time, small marginal gains of only 1% can amount to large improvements [91,92,93]. Delaunay states “registries are a manifestation of the evaluation culture. Thus, their widespread development in some countries (such as Scandinavian, Australia, UK) and their virtual absence in others (such as southern European countries) highlights the impact of cultural differences on healthcare evaluation” [94]. Though newer registries such as those from Spain, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy do not yet offer publicly available data comparing hospitals, other established registries, such as the NHFD, the IHFD and the ANZHFR, do, though they did not do so in their early stages.

Public recognition of registry participation such as in Germany—in which participation is a prerequisite of being recognised as a “Geriatric Trauma Centre”, or of achievement of standards or improvement, such as the SHFA’s “Golden Hip Award” can help raise awareness and raise the enthusiasm of healthcare professionals and administrators initially not aware of issues regarding the hip fracture care process. At a global level, the recent award in a world-wide WHO competition to the Spanish RNFC hip fracture audit as the best healthcare initiative to benefit elderly patients did much to raise the profile of hip fracture care internationally [95]. Though the reality of fragility fracture management can be very different in regions such as Southeast Asia and Latin America in comparison to Northern Europe, the same general principles apply for registry implementation. It is important, while maintaining a minimum common dataset, to tailor audit data sets to each country’s particular social and healthcare characteristics, as small local gains can lead to significant improvements and healthcare savings over time, especially in regions with rapidly growing elderly populations.

Several nascent registries arose as collaborative initiatives by scientific societies, as in Australia and New Zealand, Spain, Italy, France and Germany. The number of disciplines actively participating in these registries is variable, with some depending almost exclusively on orthopaedic surgeons and/or geriatricians, and others more widely inclusive. It is important for the healthcare providers and governments to recognise the importance of these registries as instruments for assessment of variability, benchmarking and quality improvement. The cost of maintaining a national registry is a small fraction of the overall expense of hip fractures on a healthcare system; the care of 3.5 million fragility fractures which occurred in the European Union in 2010 was estimated to have cost 37 billion euros [96]. Meanwhile, the UK NHFD has been estimated to cost approximately 0.5% per case of the total cost of hip fracture care [7]. Improvements in care processes and outcomes of good audits allow for cost savings many times higher than the cost of maintaining the audit itself. It is much more expensive to ignore current information when deciding policy than it is to invest in obtaining that information through audits. Audit provides information with the potential to deliver care that is both better and cheaper, which translates into a brief but effective formulation: “If you think information’s expensive, try ignorance”.

7 New Developments in Fracture Audit

Electronic health records (EHR) may make manual entry of many of the variables such as time of admission or surgery superfluous. However, the large number and variability of providers of EHRs and operating systems make automated data difficult, and healthcare administrations should consider automated data extraction for registry analysis when choosing one EHR system over another.

Automation of data reporting allows for real-time data evaluation and communication: prompt recognition of changes in the care process or adverse effects allows for quick responses by healthcare professionals and a more direct sense of their participation in audit. This is in contrast to the often cumbersome and sterile annual reports in which it is difficult to establish connections between actions and their results.

The UK NHFD webpage is exemplary in that sense [97], with online charts updated every 2 months comparing individual hospital, regional and national overall performances and their evolution over time, as well as performance in relation to different standards, including the quartiles achieved for each indicator. With increasing numbers of web-based registries, automation of these reports is feasible, with the Baltic Fracture Consortium using the R programming language to offer real-time statistical reports (including analyses such as Fisher’s test to assess for significance of complication rates) to participants [42].

In line with the regionalisation strategy promoted by the FFN, establishment of new fragility fracture audits should be encouraged and supported, especially in regions likely to be most seriously affected by the fragility fracture pandemic, such as Asia and Latin America. Pilot studies have revealed the reality of surgical delay in countries such as India [98], Mexico [99], Peru [100]—with only 30, 10.5 and 5.3% receiving surgery within 48 h of hospital admission, respectively—or the Mediterranean region, with Portugal, Italy and Spain among the four countries of the OECD with the lowest proportion of hip fractures operated on in less than 48 h [6]. This is far from what is considered standard in Western countries with longer established hip fracture audit, and the scope for improvement is large. But with clinically led, web-based hip fracture audit established as a mature technology supporting the substantial international expansion of effective quality improvement in hip fracture care in recent years, there are now grounds for cautious optimism about facing up to the challenge of care for the impending global pandemic of fragility fractures. With continuing international collaboration and the support of scientific societies such as the FFN, there is promise too for large-scale clinical and epidemiological research to improve the evidence-base for hip fracture care, and thus to create a virtuous cycle of continuing improvement in care, outcomes and cost-effectiveness over the coming decades.

References

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359(9319):1761–1767

Kanis JA, Odén A, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Wahl DA, Cooper C et al (2012) A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23(9):2239–2256

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ (1992) Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 2(6):285–289

Cooper C, Cole Z, Holroyd C, Earl S, Harvey N, Dennison E et al (2011) Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 22(5):1277–1288

Voeten SC, Krijnen P, Voeten DM, Hegeman JH, Wouters MWJM, Schipper IB (2018) Quality indicators for hip fracture care, a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 29(9):1963–1985

OECD (2017) Health at a Glance 2017: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris

Currie C (2018) Hip fracture audit: creating a “critical mass of expertise and enthusiasm for hip fracture care”? Injury 49(8):1418–1423

Limb C, Fowler A, Gundogan B, Koshy K, Agha R (2017) How to conduct a clinical audit and quality improvement project. Int J Surg Oncol (N Y) 2(6):e24

Kärrholm J (2010) The Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (https://www.shpr.se). Acta Orthop 81(1):3–4

Robertsson O, Ranstam J, Sundberg M, W-Dahl A, Lidgren L (2014) The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Bone Joint Res 3(7):217–222

Thorngren K-G (2009) National registration of hip fractures in Sweden. In: European Instructional Lectures. Springer. pp 11–18

Currie CT, Hutchison JD (2005) Audit, guidelines and standards: clinical governance for hip fracture care in Scotland. Disabil Rehabil 27(18–19):1099–1105

Parker MJ, Currie CT, Mountain JA, Thorngren K-G (1998) Standardised Audit of Hip Fracture in Europe (SAHFE). Hip Int 8(1):10–15

The Royal College of Physicians (2017) National Hip Fracture Database annual report 2018. eISBN 978-1-86016-736-2 [Internet]. https://nhfd.co.uk/20/hipfractureR.nsf/docs/2018Report

Bunning T, Currie CT (2017) Final report of the Hip Fracture Audit Database (HFAD) Pilot Phase [Internet]. Crown Informatics Limited. https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/hfad_final_report_2017.pdf

Gjertsen J-E, Engesæter LB, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Steindal K, Vinje T et al (2008) The Norwegian hip fracture register: experiences after the first 2 years and 15,576 reported operations. Acta Orthop 79(5):583–593

Röck ND, Hjetting AK (2017) Dansk Tværfagligt Register for Hoftenære Lårbensbrud Dokumentalistrapport [Internet]. https://www.sundhed.dk/content/cms/62/4662_hofte-fraktur-årsrapport_2017.pdf

Irish Hip Fracture Database National Report 2018 (2019) National Office of Clinical Audit. [Internet]. National Office of Clinical Audit, Dublin. https://www.noca.ie/publications

Australian and New Zealand National Hip Fracture Registry (2018) ANZHFR bi-national annual report of hip fracture care 2018. ISBN 978-0-7334-3824-0 [Internet]. http://anzhfr.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2018-ANZHFR-Annual-Report-FULL-FINAL.pdf

Arbeitsgemeinschaft Alterstraumatologie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie e.V (2018) AUC—Akademie der Unfallchirurgie GmbH. Jahresbericht 2018—AltersTraumaRegister DGU® für den Zeitraum 2017 [Internet]. http://www.alterstraumaregister-dgu.de/fileadmin/user_upload/alterstraumaregister-dgu.de/docs/Allgemeiner_ATR_Jahresbericht.pdf

Dutch Hip Fracture Audit (2018) DHFA Jaarrapportage 2017 [Internet]. https://dica.nl/jaarrapportage-2017/dhfa

Voeten SC, Arends AJ, Wouters MWJM, Blom BJ, Heetveld MJ, Slee-Valentijn MS, et al (2019) The Dutch Hip Fracture Audit: evaluation of the quality of multidisciplinary hip fracture care in the Netherlands. Arch Osteoporos [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 25];14(1). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6397305/

Zurlo A, Bellelli G (2018) Orthogeriatrics in Italy: the Gruppo Italiano di Ortogeriatria (GIOG) audit on hip fractures in the elderly. Geriatric Care 4(2):7726

Ojeda-Thies C, Sáez-López P, Currie CT, Tarazona-Santalbina FJ, Alarcón T, Muñoz-Pascual A et al (2019) Spanish National Hip Fracture Registry (RNFC): analysis of its first annual report and international comparison with other established registries. Osteoporos Int 30(6):1243–1254

Thomson S, Osborn R, Squires D, Reed SJ (2011) International profiles of health care systems 2011: Australia, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States

Rikshöft Årsrapport 2017 [Internet] (2018) RIkshöft. https://rikshoft.se/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/rikshoft_rapport2017_kompl181002.pdf

Scottish Hip Fracture Audit (2018) Hip fracture care pathway report 2018 [Internet]. https://www.shfa.scot.nhs.uk/Reports/_docs/2018-08-21-SHFA-Report.pdf

PERFECT project (2016) Perusraportit—THL [Internet]. Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos. http://thl.fi/fi/tutkimus-ja-kehittaminen/tutkimukset-ja-hankkeet/perfect/osahankkeet/lonkkamurtuma/perusraportit

Nasjonalt Register for Leddproteser. Nasjonalt Hoftebruddregister. Nasjonalt Korsbåndregister. Nasjonalt Barnehofteregister. Rapport 2017. ISSN 1893-8914 [Internet]. http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/Rapporter/Rapport2018.pdf

Kaiser Permanente National Implant Registries. 2017 annual report [Internet]. Kaiser Permanente. https://national-implantregistries.kaiserpermanente.org/Media/Default/documents/2017%20Implant%20Registry%20FINAL%20v2.pdf

Irish Hip Fracture Database National Report 2016 (2017) Dublin: National Office of Clinical Audit. ISSN 2565-5388 [Internet]. https://www.noca.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Irish-Hip-Fracture-Database-National-Report-2016-FINAL.pdf

Chow SK-H, Qin J-H, Wong RM-Y, Yuen W-F, Ngai W-K, Tang N et al (2018) One-year mortality in displaced intracapsular hip fractures and associated risk: a report of Chinese-based fragility fracture registry. J Orthop Surg Res 13(1):235

Leung KS, Yuen WF, Ngai WK, Lam CY, Lau TW, Lee KB et al (2017) How well are we managing fragility hip fractures? A narrative report on the review with the attempt to setup a Fragility Fracture Registry in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 23(3):264–271

Abdullah MAH, Abdullah AT (2009) National Orthopaedic Registry of Malaysia (NORM)—Hip Fracture Registry. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: abd

Sibai AM, Nasser W, Ammar W, Khalife MJ, Harb H, Fuleihan GE-H (2011) Hip fracture incidence in Lebanon: a national registry-based study with reference to standardized rates worldwide. Osteoporos Int 22(9):2499–2506

Keshtkar A, Khashayar P, Etemad K, Dini M, Ebrahimi M, Mohammadi Z, et al (2013) Iranian Hip Fracture Registry (IHFR): a basic framework for improving quality of care in patients with osteoporotic fracture. S60 p

Meybodi HA, Heshmat R, Maasoumi Z, Soltani A, Hossein-nezhad A, Keshtkar AA et al (2008) Iranian osteoporosis research network: background, Mission and its role in osteoporosis. Management 1:1–6

Viveros-García J, Robles-Almaguer E, Albrecht-Junghanns R, López-Cervantes R, López-Paz C, Olascoaga-Gómez de León A et al (2019) Mexican Hip Fracture Audit (ReMexFC): objectives and methodology. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol 11(3):115–118

World Health Organization (2019) World health statistics overview 2019: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 25]; https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311696

Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, Fukutaki K, Fullman N, McGaughey M et al (2018) Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 392(10159):2052–2090

BC Hip Fracture Redesign Project [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 25]. http://www.hiphealth.ca/research/research-projects/Hip-Fracture-Redesign/

Registry—BFCC [Internet]. https://www.bfcc-project.eu/registry.html

Sathiyakumar V, Greenberg SE, Molina CS, Thakore RV, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK (2015) Hip fractures are risky business: an analysis of the NSQIP data. Injury 46(4):703–708

Ottesen TD, McLynn RP, Galivanche AR, Bagi PS, Zogg CK, Rubin LE et al (2018) Increased complications in geriatric patients with a fracture of the hip whose postoperative weight-bearing is restricted: an analysis of 4918 patients. Bone Joint J 100-B(10):1377–1384

Shelton T, Hecht G, Slee C, Wolinsky P (2019) A comparison of geriatric hip fracture databases. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 27(3):e135–e141

Bohl DD, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN (2014) Nationwide Inpatient Sample and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program give different results in hip fracture studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(6):1672–1680

Smektala R, Endres HG, Dasch B, Maier C, Trampisch HJ, Bonnaire F et al (2008) The effect of time-to-surgery on outcome in elderly patients with proximal femoral fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 9:171

Smektala R, Hahn S, Schräder P, Bonnaire F, Schulze Raestrup U, Siebert H et al (2010) Medial hip neck fracture: influence of pre-operative delay on the quality of outcome. Results of data from the external in-hospital quality assurance within the framework of secondary data analysis. Unfallchirurg 113(4):287–292

Sobolev B, Guy P, Sheehan KJ, Kuramoto L, Sutherland JM, Levy AR et al (2018) Mortality effects of timing alternatives for hip fracture surgery. CMAJ 190(31):E923–E932

Sheehan KJ, Filliter C, Sobolev B, Levy AR, Guy P, Kuramoto L et al (2018) Time to surgery after hip fracture across Canada by timing of admission. Osteoporos Int 29(3):653–663

Lee Y-K, Yoon B-H, Nho J-H, Kim K-C, Ha Y-C, Koo K-H (2013) National trends of surgical treatment for intertrochanteric fractures in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 28(9):1407–1408

Lee Y-K, Ha Y-C, Park C, Koo K-H (2013) Trends of surgical treatment in femoral neck fracture: a nationwide study based on claim registry. J Arthroplast 28(10):1839–1841

Johansen A, Golding D, Brent L, Close J, Gjertsen J-E, Holt G et al (2017) Using national hip fracture registries and audit databases to develop an international perspective. Injury 48(10):2174–2179

Sáez-López P, Brañas F, Sánchez-Hernández N, Alonso-García N, González-Montalvo JI (2017) Hip fracture registries: utility, description, and comparison. Osteoporos Int 28(4):1157–1166

Griffiths F, Mason V, Boardman F, Dennick K, Haywood K, Achten J et al (2015) Evaluating recovery following hip fracture: a qualitative interview study of what is important to patients. BMJ Open 5(1):e005406

Parker MJ (2008) Databases for hip fracture audit. Acta Orthop 79(5):577–579

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) [Internet]. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02016R0679-20160504

GDPR (2019) Guidance for Clinical Audit, Version 2 [Internet]. National Office of Clinical Audit. http://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/noca-uploads/general/NOCA_GDPR_Guidance_for_Clinical_Audit_version_2_Updated_June_2019.pdf

Lilford RJ, Brown CA, Nicholl J (2007) Use of process measures to monitor the quality of clinical practice. BMJ 335(7621):648–650

Burns EM, Rigby E, Mamidanna R, Bottle A, Aylin P, Ziprin P et al (2012) Systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J Public Health (Oxf) 34(1):138–148

Dalal S, Roy B (2009) Reliability of clinical coding of hip facture surgery: implications for payment by results? Injury 40(7):738–741

Pitches DW, Mohammed MA, Lilford RJ (2007) What is the empirical evidence that hospitals with higher-risk adjusted mortality rates provide poorer quality care? A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res 7:91

Neuburger J, Currie C, Wakeman R, Tsang C, Plant F, De Stavola B et al (2015) The impact of a national clinician-led audit initiative on care and mortality after hip fracture in England: an external evaluation using time trends in non-audit data. Med Care 53(8):686–691

Wise J (2015) Hip fracture audit may have saved 1000 lives since 2007. BMJ 351:h3854

Condorhuamán-Alvarado PY, Pareja-Sierra T, Muñoz-Pascual A, Sáez-López P, Ojeda-Thies C, Alarcón-Alarcón T et al (2019) First proposal of quality indicators and standards and recommendations to improve the healthcare in the Spanish National Registry of Hip Fracture. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 54(5):257–264

Scottish Hip Fracture Audit (2018) Scottish standards of care for hip fracture patients 2018 [Internet]. https://www.shfa.scot.nhs.uk/_docs/2018/Scottish-standards-of-care-for-hip-fracture-patients-2018.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety & Quality in Health Care (2016) Hip fracture care: clinical care standard [Internet]. http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/clinical-care-standards/hip-fracture-care-clinical-care-standard/

Whitaker SR, Nisar S, Scally AJ, Radcliffe GS (2019) Does achieving the “Best Practice Tariff” criteria for fractured neck of femur patients improve one year outcomes? Injury 50(7):1358–1363

Quality statements|Hip fracture in adults|Quality standards|NICE [Internet]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs16/chapter/Quality-statements

British Orthopaedic Association (2019) BOAST—The Care of the Older or Frail Orthopaedic Trauma Patient [Internet]. https://www.boa.ac.uk/resources/boa-standards-for-trauma-and-orthopaedics/boast-frailty.html

Metcalfe D, Zogg CK, Judge A, Perry DC, Gabbe B, Willett K et al (2019) Pay for performance and hip fracture outcomes: an interrupted time series and difference-in-differences analysis in England and Scotland. Bone Joint J 101-B(8):1015–1023

Ferguson KB, Halai M, Winter A, Elswood T, Smith R, Hutchison JD et al (2016) National audits of hip fractures: are yearly audits required? Injury 47(2):439–443

White SM, Moppett IK, Griffiths R, Johansen A, Wakeman R, Boulton C et al (2016) Secondary analysis of outcomes after 11,085 hip fracture operations from the prospective UK Anaesthesia Sprint Audit of Practice (ASAP-2). Anaesthesia 71(5):506–514

Boulton C, Currie C, Griffiths R, Grocott M, Johansen A, Majeed A, et al (2014) Anaesthesia Sprint Audit of Practice 2014. p 64

Metcalfe D, Costa ML, Parsons NR, Achten J, Masters J, Png ME et al (2019) Validation of a prospective cohort study of older adults with hip fractures. Bone Joint J 101-B(6):708–714

Costa ML, Griffin XL, Achten J, Metcalfe D, Judge A, Pinedo-Villanueva R, et al (2016) World Hip Trauma Evaluation (WHiTE): framework for embedded comprehensive cohort studies. BMJ Open [Internet]. 6(10). https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/10/e011679

Montori VM (2017) Big Science for patient centred care. BMJ [Internet]. 359. https://www.bmj.com/content/359/bmj.j5600

Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ (1992) Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985–1989. J Bone Miner Res 7(2):221–227

Pizzato S, Trevisan C, Lucato P, Girotti G, Mazzochin M, Zanforlini BM et al (2018) Identification of asymptomatic frailty vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women. Bone 113:89–94

Vertebral Fracture Sprint Audit [Internet] (2019) RCP London. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/vertebral-fracture-sprint-audit

Wennergren D, Möller M (2018) Implementation of the Swedish Fracture Register. Unfallchirurg 121(12):949–955

Svenska Frakturregistret [Internet]. https://sfr.registercentrum.se/

Thien TM, Chatziagorou G, Garellick G, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Mäkelä K et al (2014) Periprosthetic femoral fracture within two years after total hip replacement: analysis of 437,629 operations in the nordic arthroplasty register association database. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96(19):e167

Palan J, Smith MC, Gregg P, Mellon S, Kulkarni A, Tucker K et al (2016) The influence of cemented femoral stem choice on the incidence of revision for periprosthetic fracture after primary total hip arthroplasty: an analysis of national joint registry data. Bone Joint J 98-B(10):1347–1354

Kristensen TB, Dybvik E, Furnes O, Engesæter LB, Gjertsen J-E (2018) More reoperations for periprosthetic fracture after cemented hemiarthroplasty with polished taper-slip stems than after anatomical and straight stems in the treatment of hip fractures: a study from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register 2005 to 2016. Bone Joint J 100-B(12):1565–1571

Fracture Liaison Service Database (FLS-DB) [Internet] (2015) RCP London. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/fracture-liaison-service-database-fls-db

Osteoporosis Canada (2018) Report from Osteoporosis Canada’s first national FLS audit [Internet]. https://fls.osteoporosis.ca/wp-content/uploads/Report-from-Osteoporosis-Canadas-first-national-FLS-audit.pdf

Registro REFRA [Internet]. Seiomm. https://seiomm.org/registro-refra/

Seibel MJ, Mitchell P (2018) Secondary fracture prevention: an international perspective. Academic Press, New York

British Orthopaedic Association (2007) The care of patients with fragilty fracture [internet]. British Orthopaedic Association, London. http://www.bgs.org.uk/pdf_cms/pubs/Blue%20Book%20on%20fragility%20fracture%20care.pdf

Lemer C, Cheung R, Klaber R, Hibbs N (2016) Understanding healthcare processes: how marginal gains can improve quality and value for children and families. Arch Dis Childhood Educ Pract 101(1):31–37

Yousri TA, Khan Z, Chakrabarti D, Fernandes R, Wahab K (2011) Lean thinking: can it improve the outcome of fracture neck of femur patients in a district general hospital? Injury 42(11):1234–1237

Sayeed Z, Anoushiravani A, El-Othmani M, Barinaga G, Sayeed Y, Cagle P et al (2018) Implementation of a hip fracture care pathway using lean six sigma methodology in a level I trauma center. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 26(24):881–893

Delaunay C (2015) Registries in orthopaedics. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 101(1 Suppl):S69–S75

Executive Board 144 (2019). His highness Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah prize for research in health care for the elderly and in health promotion [Internet]. World Health Organization, Geneva. https://extranet.who.int/iris/restricted/handle/10665/327207

Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J et al (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 8(1–2):136

The National Hip Fracture Database [Internet]. https://www.nhfd.co.uk/

Rath S, Yadav L, Tewari A, Chantler T, Woodward M, Kotwal P et al (2017) Management of older adults with hip fractures in India: a mixed methods study of current practice, barriers and facilitators, with recommendations to improve care pathways. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):55

Viveros-García J, Robles-Almaguer E, Albrecht-Junghanns R, López-Cervantes R, López-Paz C, Olascoaga-Gómez de León A, et al (2019) Mexican hip fracture audit: results from the pilot phase. In: 8th FFN global congress 2019. p 116

Palomino L, Ramírez R, Vejarano J, Ticse R (2016) Fractura de cadera en el adulto mayor: la epidemia ignorada en el Perú. Acta Méd Peruana 33(1):15–20

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ojeda-Thies, C., Brent, L., Currie, C.T., Costa, M. (2021). Fragility Fracture Audit. In: Falaschi, P., Marsh, D. (eds) Orthogeriatrics. Practical Issues in Geriatrics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48126-1_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48126-1_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-48125-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-48126-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)