Published online May 10, 2019. doi: 10.5313/wja.v8.i2.13

Peer-review started: October 31, 2018

First decision: November 8, 2018

Revised: March 7, 2019

Accepted: March 24, 2019

Article in press: March 25, 2019

Published online: May 10, 2019

Fascia iliaca compartment blocks (FIBs) have been used to provide postoperative analgesia after total hip arthroplasty (THA). However, evidence of their efficacy remains limited. While pain control appears to be satisfactory, quadriceps weakness may be an untoward consequence of the block. Prior studies have shown femoral nerve blocks and fascia iliaca blocks as being superior for pain control and ambulation following THA when compared to standard therapy of parenteral pain control. However, most studies allowed patients to ambulate on post-operative day (POD) 2-3, whereas new guidelines suggest ambulation on POD 0 is beneficial.

To determine the effect of FIB after THA in patients participating in an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of patients undergoing THA with or without FICBs and their ability to ambulate on POD 0 in accordance with ERAS protocol. Perioperative data was collected on 39 patients who underwent THA. Demographic data, anesthesia data, and ambulatory outcomes were compared.

Twenty patients had FIBs placed at the conclusion of the procedure, while 19 did not receive a block. Of the 20 patients with FIB, only 1 patient was able to ambulate. Of the 19 patients without FIB blocks, 17 were able to ambulate. All patients worked with physical therapy 2 h after arriving in the post-anesthesia care unit on POD 0.

Our data suggests an association between FIB and delayed ambulation in the immediate post-operative period.

Core tip: We evaluated the ambulatory ability of total hip arthroplasty patients in the immediate post-operative period to determine if there was an association with the use of fascia iliaca blocks and hindered ambulatory ability. We observed that in accordance with enhanced recovery after surgery protocol, which requires patients to ambulate on POD 0, there was an association with fascia iliaca block and delayed ambulation.

- Citation: Metesky JL, Chen J, Rosenblatt M. Enhanced recovery after surgery pathway: The use of fascia iliaca blocks causes delayed ambulation after total hip arthroplasty. World J Anesthesiol 2019; 8(2): 13-18

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6182/full/v8/i2/13.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5313/wja.v8.i2.13

The frequency of total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgery is increasing, with the number of procedures performed in the United States being greater than 300000 annually. With such a high volume, many hospitals have implemented enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols to help fast track these joint replacement patients, the goal being to reduce the stress response following surgery, promote early recovery, and lead to a decrease length of hospital stay without any increase in readmission rates. While the ERAS protocols still promote adequate pain control, the addition of early ambulation has resulted in changes to the anesthetic plans, to ensure that patients will be able to walk on the day of their surgery.

Adequate postoperative pain control is not only crucial for early ambulation; it is also associated with a decrease in length of hospital stay, and reductions in post-operative complications such as deep vein thrombus and pulmonary embolism[1]. The topic of what is the optimum analgesia regimen following THR is heavily debated and has yet to yield a universal consensus. With many options for pain control, including oral narcotics, local anesthetic infiltration, femoral nerve block, fascia iliaca block, patient- controlled analgesia, and intrathecal opioids, it is difficult to determine which is superior. Although it has been shown that opioids can adequately control pain, the unwanted side effects of nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, pruritus, and urinary retention can be problematic. In addition, minimizing opioid consumption in this aging population who often have multiple co-morbidities is advantageous.

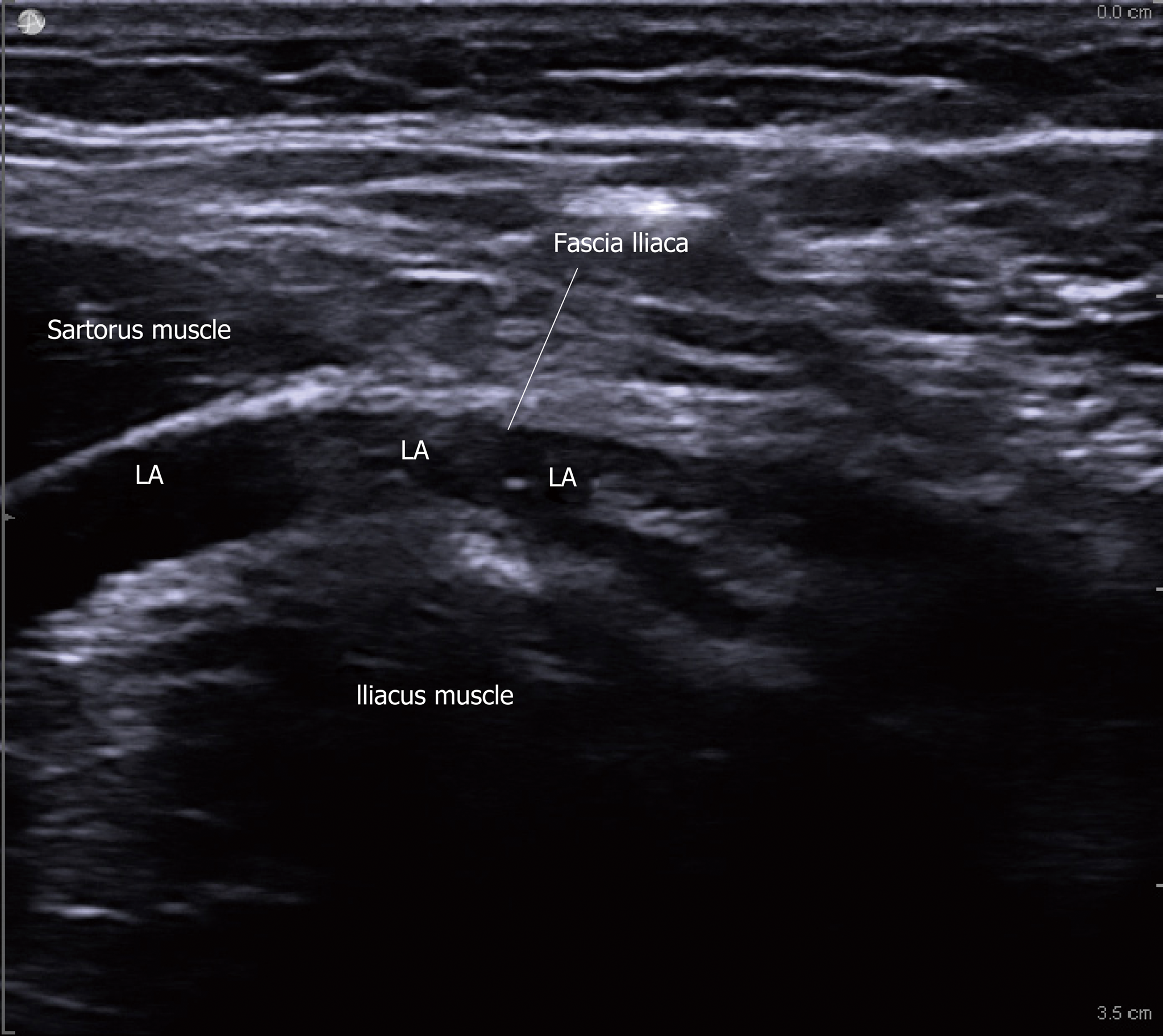

Intrathecal morphine (ITM) has fallen out of favor because of these unwanted side effects. When ITM was compared to local infiltration analgesia (LIA), it was shown that LIA provided superior analgesia effects within the first 24 h compared to ITM following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and THA, and was associated with decreased rates of nausea, vomiting, and pruritus while having no effect of hospital length of stay[2]. While it is recognized that femoral nerve blocks (FNB) have been replaced by adductor canal blocks (ACB) for analgesia following TKA[3], there remains a lack of evidence for the best management of pain following THA. Although its effect is controversial, FIB has been utilized for procedures in hip, anterior thigh, and knee. In this block, LA is deposited in the compartment beneath the fascia iliaca ligament at the superficial fascial layer of the iliopsoas muscle near the anterior edge of the ilium. It creates a fluid- filled compartment which, in turn, spreads the LA cephalad beneath the fascia to reach the nerves of the lumbar plexus-the lateral femoral cutaneous, femoral, and obturator nerves. We hypothesized, that performing a FIB with dilute local anesthetic concentration might provide adequate analgesia, while minimizing the motor block. Thus, patients would have better pain control and allow ambulation in the immediate post-operative period in accordance with ERAS protocol. This retrospective review aims to access the patient’s ambulation ability immediately after THA by comparing ambulation in patients who received FICB with those who did not.

After approval by Institutional Review Board, we reviewed the anesthetic records (CompuRecord®, Philips, MA) and medical records (Prism®, GE Healthcare, United Kingdom) of all undergoing THA with or without FIBs with a single block anesthesiologist from July to December 2016. Patients were evaluated by a member of the physical therapy (PT) team approximately 2 h after admission to the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU). Motor strength was evaluated, and if deemed adequate, the patient was permitted to stand and then ambulate. In addition to patient demographics, we also examined the anesthetic agents administered intra-operatively, looking for differences in anesthetic techniques; spinal vs general anesthesia, type of local anesthetic, and adjuvant medications given.

All ultrasound-guided FIBs were performed by residents supervised by a single attending and using a standard technique. The femoral nerve and artery were identified on ultrasound and after moving laterally, a 22 gauge block needle was inserted below the junction of the lateral 1/3 and medial 2/3 of the inguinal ligament as described by a research[4]. Using an in-plane approach, 40 mL of 0.2% ropivicaine was injected beneath the fascia iliaca at the superficial fascial layer as showed in Figure 1

Group variable data were analyzed by parametric t-test: Based on our sample of 39 patients, it was concluded that the true probability a patient with no block is able to ambulate (89.5%) is higher than the true probability that a patient who underwent FIB is able to ambulate (5%). These results are statistically significant with 95% confidence and the two-tailed p value is less than 0.0001.

Perioperative data was collected on 39 patients who underwent THA. Demographic data appears in Table 1. The majority of patients received a single shot spinal as the primary anesthetic for their THA, with either isobaric bupivacaine (10-15 mg) or hyperbaric bupivacaine (12-15 mg). Twenty patients had FIBs placed at the conclusion of the procedure, while 19 did not receive a block. Of the 20 patients with FIB, only 1 patient was able to ambulate. Eighteen patients did not ambulate secondary to decreased muscle strength and sensation, while 1 patient was unable to walk due to severe nausea. Of the 19 patients without FIB blocks, 17 were able to ambulate. Two patients were not able to ambulate secondary to lethargy, but both were able to stand up with minimal assistance.

| Demographics | FIB | No block |

| Gender (F:M) | 12:08 | 7:12 |

| Average age (yr) | 67.1 | 64.6 |

| Average BMI | 28.36 | 30.08 |

| Anesthesia technique | ||

| Spinal (isobaric:hyperbaric) | 11:03 | 14:01 |

| Combined spinal-epidural | 1 | 4 |

| Epidural | 1 | 0 |

| General anesthesia | 4 | 0 |

| Outcomes | ||

| Ability to ambulate | 1 (5%) | 17 (89.5%) |

Although previous publications have promoted the use of FIB to provide excellent analgesia following THA as explained by Mudumbai et al[5], we observed that they were associated with delayed ambulation in the immediate postoperative period. While the FIB blocks the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve which is a sensory nerve, local anesthetic spread medially may result in direct block of the femoral nerve, causing quadriceps weakness and an inability to ambulate. Alternatively, there may be some retrograde spread of the local anesthetic into the lumbar plexus, which causes both weakness of quadriceps in addition to hip adductor weakness from obturator nerve involvement.

The concentration of local anesthetic used in FIB (0.2% ropivicaine) should not be enough to cause significant femoral motor blockade; however, the volume of 40cc may be a contributing factor.

Isobaric bupivacaine may be another contribution to prolonged muscle weakness and the prevention of immediate ambulation in the PACU. Our data indicate that this is not the case, since the ambulating and non- ambulating groups had similar spinal doses.

While FIB appears to delay ambulation, we also sought to determine if pain scores were improved in the block group. However, due to the retrospective nature of the study and lack of guidelines for documentation of pain scores, medications administered, and PACU length of stay; it was difficult to find consistent and reliable information. Further studies need to be done to address this issue in a standardized fashion.

With THA becoming a shorter stay, and in some cases an ambulatory procedure, it is important to develop ERAS protocols, which will provide excellent pain control, while still allowing prompt post-operative ambulation. Though FIB may provide post-operative analgesia, it appears to be preventing ambulation and should not be included in an ambulatory THA pathway until further studies examine this relationship.

Peripheral nerve block has provided excellent analgesia for total joint replacement procedures. However, its associated motor weakness is undesirable in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol. While Fascia iliaca compartment blocks (FIBs) have been shown to be satisfactory in pain control and minimize quadriceps weakness after total hip arthroplasty (THA), their value is still debatable. Prior studies have demonstrated the superiority of FIBs and femoral nerve blocks for pain control and ambulation following THA as compared to standard therapy of parenteral analgesics on postoperative day (POD) 2-3. However, there are few studies that investigate how this block affects the ambulation in POD 0 after THA, the time of ambulation that is recommended and considered beneficial under the new ERAS guidelines.

The use and popularity of ERAS protocols has led to the need for a common post-operative anesthetic plan following THA. We sought to examine the relationship between FIB and delayed ambulation after THA.

We collected perioperative data on 39 patients following THA, some with and without FIBs, and evaluated their ability to ambulate in the immediate post-operative period on POD 0 with a physical therapy team.

In this retrospective cohort study, the medical record and anesthetic records of patients undergoing THA with or without FIBs by a single physician throughout 2016 were reviewed. Patients that were evaluated by physical therapists promptly, within two hours, after arrival at the post-anesthesia care unit were identified. These patients were all evaluated for motor strength and if appropriate, were allowed to stand and ambulate. We additionally reviewed patient demographics as well as anesthetic agents administered intra-operatively in order to look for differences in anesthetic technique (i.e., spinal vs general anesthesia, adjuvant medications given, and type of local anesthetic.) that may affect the early ambulation.

We found that all but one patient in the FIB group were unable to ambulate within 2 h post-operative, mainly due to weakness, significantly lower than the patients without FIB. While pain control appeared to be adequate, the lack of ambulatory ability poised a problem with early ambulation as part of the ERAS protocol.

Out data indicated that there is significant correlation associated between the FIB and the delayed ambulation on POD 0 after THA. Despite the fact that the ERAS pathway of THA emphasized early ambulation during the immediate post-operative period and shorter stay in hospital, FIB appears to be interfering with this goal. Therefore, this post-operative pain control block should be excluded from the ERAS pathway of THA until further study.

This study is based on the retrospective reviewing of the data and some crucial information, such as degree of the motor weakness and Oxford Hip Score in both pre and post-operatively, are not available. Therefore, to objectively determine the efficacy of FIB for post-operative pain management and its role in the ERAS protocol, a prospective control study should be consideration. Going forward, the ideal pain management means for THA needs to be further examined in a way that can provide a common pathway for both pain control and early ambulation that satisfies the patients’ comfort as well as ERAS protocols.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Anesthesiology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

STROBE Statement: All authors have read the STROBE Statement and checklist of items and the manuscript was prepared and revised accordingly.

P-Reviewer: Anand A, Wyatt MC S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Zhang P, Li J, Song Y, Wang X. The efficiency and safety of fascia iliaca block for pain control after total joint arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6592. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jia XF, Ji Y, Huang GP, Zhou Y, Long M. Comparison of intrathecal and local infiltration analgesia by morphine for pain management in total knee and hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2017;40:97-108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Auyong DB, Allen CJ, Pahang JA, Clabeaux JJ, MacDonald KM, Hanson NA. Reduced Length of Hospitalization in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty Patients Using an Updated Enhanced Recovery After Orthopedic Surgery (ERAS) Pathway. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:1705-1709. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brisbane Orthopaedic & Sports Medicine Centre Writing Committee; McMeniman TJ, McMeniman PJ, Myers PT, Hayes DA, Cavdarski A, Wong MS, Wilson AJ, Jones MA, Watts MC. Femoral nerve block vs fascia iliaca block for total knee arthroplasty postoperative pain control: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:1246-1249. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mudumbai SC, Kim TE, Howard SK, Giori NJ, Woolson S, Ganaway T, Kou A, King R, Mariano ER. An ultrasound-guided fascia iliaca catheter technique does not impair ambulatory ability within a clinical pathway for total hip arthroplasty. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016;69:368-375. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |