Published online Apr 7, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i13.1592

Peer-review started: December 25, 2018

First decision: February 21, 2019

Revised: March 6, 2019

Accepted: March 11, 2019

Article in press: March 12, 2019

Published online: April 7, 2019

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common indication for endoscopy. For refractory cases, hemostatic powders (HP) represent “touch-free” agents.

To analyze short term (ST-within 72 h-) and long-term (LT-within 30 d-) success for achieving hemostasis with HP and to directly compare the two agents Hemospray (HS) and Endoclot (EC).

HP was applied in 154 consecutive patients (mean age 67 years) with GI bleeding. Patients were followed up for 1 mo (mean follow-up: 3.2 mo).

Majority of applications were in upper GI tract (89%) with following bleeding sources: peptic ulcer disease (35%), esophageal varices (7%), tumor bleeding (11.7%), reflux esophagitis (8.7%), diffuse bleeding and erosions (15.3%). Overall ST success was achieved in 125 patients (81%) and LT success in 81 patients (67%). Re-bleeding occurred in 27% of all patients. In 72 patients (47%), HP was applied as a salvage hemostatic therapy, here ST and LT success were 81% and 64%, with re-bleeding in 32%. As a primary hemostatic therapy, ST and LT success were 82% and 69%, with re-bleeding occurring in 22%. HS was more frequently applied for upper GI bleeding (P = 0.04)

Both HP allow for effective hemostasis with no differences in ST, LT success and re-bleeding.

Core tip: Hemostatic powders represent “touch-free” hemostatic agents for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding. Within this study, we analyzed the hemostatic efficacy of hemostatic powders as first line or salvage therapy in several clinical scenarios in a large cohort of prospectively included patients. As shown in our report, both hemostatic powders allow for excellent short term bleeding control while at the same time, long term efficacy over a period of 4 wk is maintained in a considerable amount of patients. No differences were observed between Hemospray and Endoclot in their hemostatic efficacy.

- Citation: Vitali F, Naegel A, Atreya R, Zopf S, Neufert C, Siebler J, Neurath MF, Rath T. Comparison of Hemospray® and Endoclot™ for the treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(13): 1592-1602

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i13/1592.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i13.1592

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding represents a major challenge for the GI endoscopist both in term of frequency, which is estimated to be 150/100000 for upper and 33/100000 for lower GI bleeding with a mortality ranging between 2 and 10%[1-3], and in terms of technical efforts to reach a stable hemostasis. As the administration of direct oral anticoagulants[4] and the use of assistant devices in terminal cardiomyopathy[5] is increasing, sufficient and effective treatment of GI bleeding is mandatory while at the same time can be clinically challenging. In the last years, endoscopists increasingly face emergency bleeding in a clinical scenario in which coagulation parameters cannot always be corrected to normal range. Further, with increasing development of advanced endoscopic therapeutic procedures, iatrogenic bleeding after endoscopic resections represents another emerging problem[6]. Conventional treatment approaches achieve hemostasis in more than 90% of cases[7], however, depending on the bleeding site and source can be technically challenging, and might not be optimal for diffuse oozing bleeding as frequently observed in patients with impaired coagulation or cancer bleeding.

Hemostatic powders (HP) act as “touch-free” agents that can be easily administrated for the treatment of GI bleeding, which are generally safe and well tolerated[8-11]. Hemospray (HS, TC-325, Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, United States) is an inert mineral based compound, which, in contact with blood, absorbs water and acts cohesively and adhesively, thereby forming a covering mechanical tamponade. By fluid absorption, HS enhances clot formation by deforming and packing erythrocytes, concentrates activated platelets with clotting factors and interacts with the fibrin matrix[12] and within 24 to 72 h, the adherent coat sloughs off into the GI lumen[10]. With his local hemostatic proprieties, first studies suggest that HS is equally effective in both patients with and without systemic antithrombotic therapy[9].

Endoclot (EC, Micro-Tech Europe, Düsseldorf, Germany) is a starch-derived agent composed of absorbable hemostatic polysaccharides. Similar to HS, in contact with blood, EC initiates a dehydration process leading to a concentration of clotting factors, platelet and erythrocytes thereby accelerating the physiological clotting cascade and the formation of a mechanical shell of gelled matrix which adheres to the bleeding tissue[13]. Although data on the efficacy of EC are still limited, first clinical evidences suggest that both HS and EC allow for effective bleeding control[8,11,14-20]. Further, no direct comparison of the efficacy of these two HP is available to date. Against this background we set off: (1) To analyze short and long term hemostatic effectiveness of HP; and (2) to compare the efficacy between the agents HS and EC in achieving hemostasis in a large cohort of patients treated for emergency GI bleeding in our center.

Prospective data collection was performed including patients who were treated with HS and EC for endoscopic hemostasis during emergency endoscopy between September 2013 and September 2017 in our university hospital. After application of HP patients were followed-up for at least one mo. After completion of follow-up (FU) of all patients data analysis was performed. The study was approved by the local institutional review board and the ethics committee of the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen Nueremberg (approval at 31 January 2018) and our study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Indications for treatment with HP were: refractory GI bleeding (e.g. due to difficult anatomical location or diffuse oozing bleeding without definite source); application of HP as salvage therapy after failure of other endoscopic methods; application of HP as prophylactic means to avoid delayed bleeding in lesions with high re-bleeding risk, application of HP as primary treatment means usage of HP as monotherapy. Primary endpoints were short term (ST, hemostasis for 72 h) and long term (LT, hemostasis for a period of 30 d) success in achieving hemostasis with HP as a primary or salvage therapy.

Re-bleeding rate (RBR) was defined as the number of the patients who showed recurrent bleeding among the patients who underwent FU. Recurrent bleeding was defined if one of these criteria had been met: (1) Hematemesis or melena; (2) a drop in hemoglobin > 2 mg/dL or transfusion of 4 or more blood packs; or (3) hemodynamic instability as previously described[10,21]. Complete Rockall Score was utilized to stratify high-risk patients. Secondary endpoint was the direct comparison of hemostatic efficiency between EC and HS.

Descriptive statistics consisted of the mean, median, SD and range. The χ2 analysis was used for discrete variables. The Fisher exact probability test was used for the 2 × 2 contingency tables, where suitable. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. The statistics were processed using the SPSS statistical program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, United States).

HP was applied a total of 239 times in 154 patients with a mean age of 67 years. The majority of the patients were male (n = 101, 66%). One child treated with HS was also included in the analysis. Clinical FU for at least one month was performed in 134 patients (87%) with a mean FU of 3.2 SD 5.5 mo (range 1-29). No patient was lost during FU; however, in 20 patients FU was not completed as they died from other causes than GI bleeding within 30 d after the first HP application. The mean complete Rockall score[22] in the total patient cohort was 7.1 with 61 (40%) patients exhibiting a Rockall score > 7 and 27 patients (18%) with a Rockall score > 8.

Therapeutic anticoagulation was present in 45 patients (29%). Of these, 17 (11%) received heparin, low molecular weight heparin or argatroban in therapeutic dosages while 17 patients (11%) and 11 patients (7%) were taking vitamin K antagonist and direct oral anticoagulants, respectively. Antiplatelet drugs were administered in 34 (22%), 8 patients received dual antiplatelet therapy (5.2%). Among co-morbidities, 20 patients had localized (13%) and 21 patients metastasized cancer (14%) while 6 patients suffered from malignant lymphoproliferative disease (4%). 40 patients (26%) suffered from liver cirrhosis and 74 patients (48%) exhibited renal insufficiency, of which 35 patients (23%) had terminal kidney failure requiring hemodialysis. 13 patients had coronary heart disease (8%). 53 patients (35%) presented with hemorrhagic shock at the time of application of HP. Vasopressors were administered in 65 patients (42%). Clinical characteristics of the total patient cohort are summarized in Table 1.

| HS and EC n = 154 | Hemospray n = 111 | Endoclot n = 32 | P value | |

| Sex (M) | 101 (65.6) | 76 (68.5) | 17 (53.1) | NS |

| Age, yr | ||||

| mean ± SD | 66.6 ± 14 | 67 ± 13.8 | 67.4 ± 15.1 | NS |

| range | 11-93 | 29-93 | 11-89 | |

| Rockall risk score | ||||

| median ± SD | 7.1 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 1.8 | NS |

| range | 2-10 | 2-10 | 2-10 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Coagulopathy | 48 (31.2) | 36 (32.4) | 6 (18.8) | NS |

| Renal insufficiency | 74 (48.1) | 53 (47.7) | 15 (46.9) | NS |

| Hemodialysis | 35 (22.7) | 26 (23.4) | 5 (15.6) | NS |

| Liver cirrhosis | 40 (26) | 32 (28.9) | 5 (15.6) | NS |

| Bleeding locale | ||||

| upper GI bleeding | 137 (89) | 102 (91.8) | 25 (78.1) | 0.04 |

| lower GI bleeding | 17 (11) | 8 (8) | 7 (21) | NS |

| Application as | ||||

| Primary therapy | 82 (53.2) | 64 (57.7) | 14 (43.8) | NS |

| Salvage therapy | 72 (46.8) | 47 (42) | 18 (56) | NS |

| Multiple applications of HP | 42 (27.3) | 27 (24.3) | 5 (15.6) | NS |

| Definite hemostatic therapies after HP failure | ||||

| Coiling | 13 (8.4) | 11 (9.9) | 1 (3.1) | NS |

| Surgery | 9 (5.8) | 7 (6.3) | 1 (3.1) | NS |

| Short term success (total) | 125 (81.2) | 92 (82.9) | 26 (81.2) | NS |

| Primary therapy | 67/82 (81.7) | 53/64 (82.8) | 11/14 (78.6) | |

| Salvage therapy | 58/72 (80.6) | 39/47 (82.9) | 15/18 (83.3) | |

| Long term success | 81/121 (66.9) | 59 (69.4) | 18 (66.7) | NS |

| Primary therapy | 45/65 (69.2) | 35/49 (71.4) | 8/13 (61.5) | |

| Salvage therapy | 36/56 (64.3) | 24/36 (66.7) | 10/14 (71.4) | |

| Re-bleeding rate | 41 (26.6) | 27 (24.3) | 8 (25) | NS |

| Primary therapy | 18/82 (21.9) | 13/64 (20.3) | 3/14 (21.4) | |

| Salvage therapy | 23/72 (31.9) | 14/47 (29.8) | 5/18 (27.8) |

In patient cohort, HP exhibited an overall ST and LT success for achieving hemostasis of 82% and 69% with a RBR of 21% when applied as primary therapy. As salvage therapy, overall ST success, LT success and RBR rate were 83%, 68% and 29%, respectively. In the cohort, no significant difference was observed for achieving hemostasis between HS and EC under primary or salvage therapy (Table 1). Due to refractory bleeding a total of 20 patients treated with HP had to undergo surgery or interventional radiology for bleeding control after failure of HPs.

The majority of patients exhibited upper GI bleeding (n = 137, 89%). Of these, 91 patients (66%) presented with Forrest Ib bleeding while 15 patients (11%) exhibited a Forrest Ia bleeding source. Further, 4 patients (3%) had Forrest III lesions. Clinical characteristics of the patients with upper GI bleeding are shown in Table 2.

| HS and EC (n = 137) | Hemospray (n = 102) | Endoclot (n = 25) | P value | |

| Sex (M) | 86 (62.8) | 68 (66.7) | 11 (44) | 0.04 |

| Age, yr | ||||

| mean ± SD | 66.4 ± 14.2 | 66.4 ± 14.0 | 67.9 ± 16.5 | NS |

| range | (11-93) | 29-93 | 11-89 | |

| Rockall risk score | NS | |||

| median ± SD | 7.1 ±1.7 | 7.1 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 1.8 | |

| range | 2-10 | 2 -10 | 2 - 10 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Coagulopathy | 45 (32.8) | 34 (33) | 5 (2) | |

| Renal insufficiency | 68 (49.6) | 59 (49) | 12 (48) | |

| Hemodialysis | 32 (23.4) | 24 (23) | 12 (48) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 38 (27.7) | 30 (29.4) | 5 (20) | |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation | 35 (25.5) | 28 (27.5) | 6 (24) | |

| Dual antiplatet therapy | 7 (5.1) | 5 (5) | 2 (8) | |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 14 (10.2) | 11 (11) | 3 (12) | |

| DOAC | 8 (5.8) | 7 (7) | 1 (4) | |

| Antiaggregation therapy | 29 (21.2) | 21 (20.6) | 7 (28) | |

| Application as | NS | |||

| Primary Therapy | 72 (52.6) | 59 (58) | 10 (40) | |

| Salvage Therapy | 65 (47.4) | 43 (42) | 15 (60) | |

| Multiple Applications of | NS | |||

| HS | 37 (27) | 24 (23) | 3 (0.12) | |

| Definite hemostatic therapies after HP failure | NS | |||

| Coiling | 13 (9.5) | 11 (11) | 1 (4) | |

| Surgery | 8 (5.8) | 7 (6.9) | 0 | |

| Short term success (total) | 113/137 (82.5) | 68/102 (66.6) | 21/25 (84) | NS |

| Primary therapy | 60/72 (83.3) | 50/59 (84.7) | 8/10 (80) | |

| Salvage therapy | 53/65 (81.5) | 36/43 (83.7) | 13/15 (86.6) | |

| Long term success | 71/108 (65.7) | 53/78 (67.9) | 15/22 (68.2) | NS |

| Primary therapy | 39/57 (68.4) | 32/45 (71) | 6/10 (60) | |

| Salvage therapy | 32/51 (62.7) | 21/33(63.6) | 9/12 (75) | |

| Re-bleeding rate | 34/137 (24.8) | 24/102 (23.5) | 4/25 (16) | NS |

| Primary therapy | 15/72 (20.8) | 11/59 (18.6) | 2/10 (20) | |

| Salvage therapy | 19/65 (29.2) | 13/43 (30.2) | 2/15 (13) |

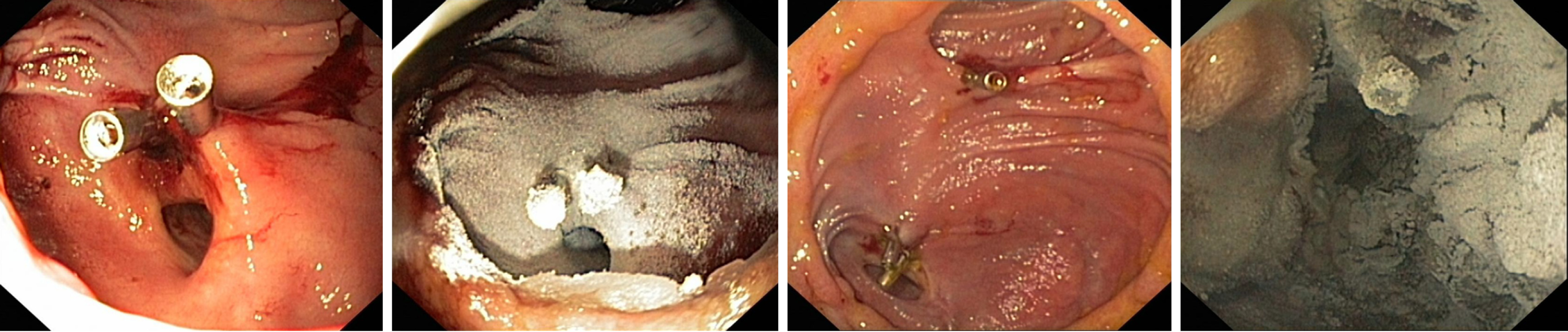

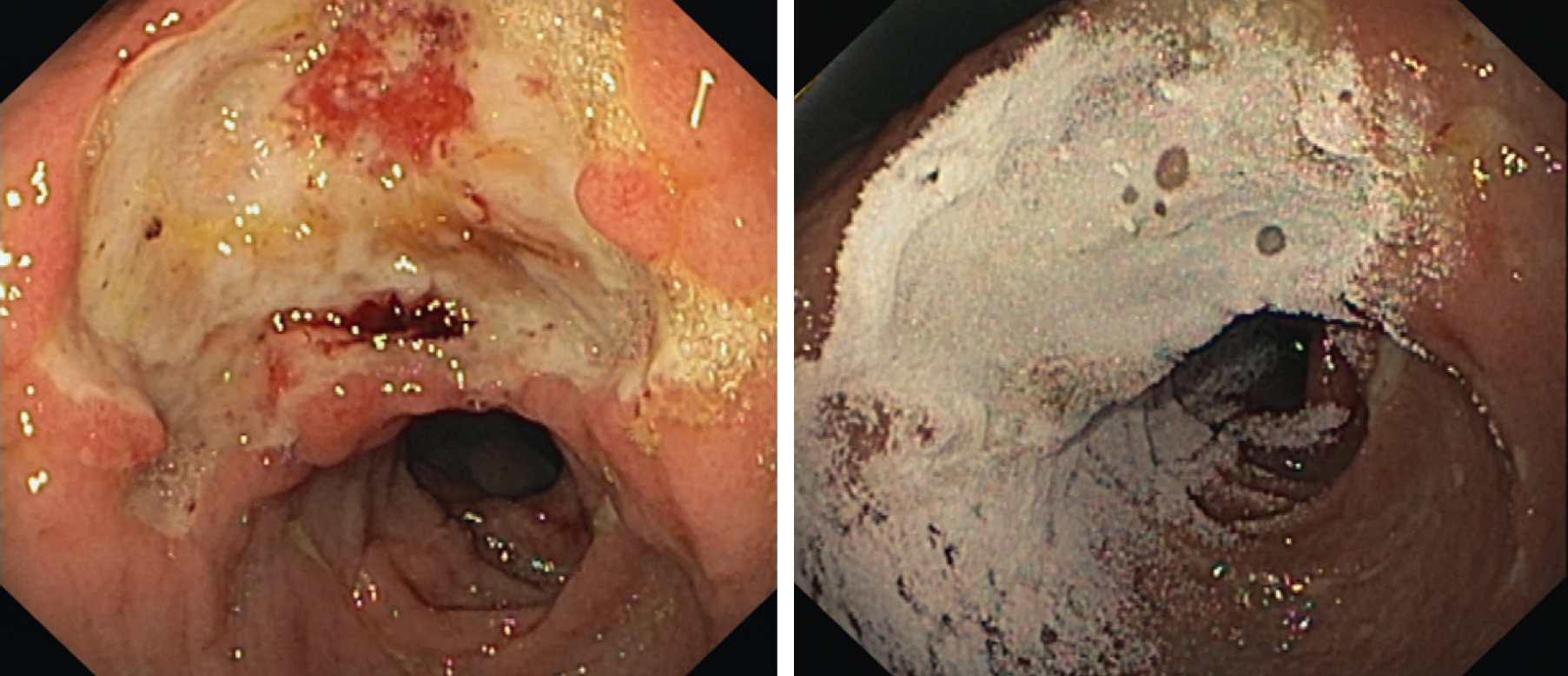

Overall, ST success of HP within the upper GI tract was achieved in 113 patients (82.5%) with LT success maintained in 71 patients (66%) and an overall RBR of 25%. HP as salvage therapy was applied in 65 patients (47%) with upper GI bleeding. The ST and LT success of HP as primary and salvage therapy is shown in Table 2. Within the upper GI Tract, bleeding was derived from the following sources: peptic ulcer disease (n = 49, gastric ulcer: n = 12; duodenal ulcer: n = 37), malignant tumor (n = 15), esophagogastric varices (n = 13), reflux esophagitis (n = 12), angiodysplasias or angioectasias (n = 8), Mallory Weiss lesions (n = 5) and diffuse oozing bleeding and erosions (n = 21). We then performed subgroup analyses on the efficacy of HP according to the bleeding location (Table 3). In peptic ulcer disease (Figures 1 and 2), HP achieved hemostasis with a ST and LT success of 80% and 57% and a RBR of 34%. When applied as a primary therapy in peptic ulcer disease, ST and LT success and RBR were 79%, 67% and 21%, respectively; when applied as a salvage therapy ST and LT were comparable (81% and 67%); however RBR was considerably higher under salvage therapy (46%). A total of 15 patients suffered from diffuse cancer bleeding, here ST and LT success were 81% and 85%, re-bleeding occurring in only 1 patient.

| HS and EC (n = 137) | Hemospray (n = 102) | Endoclot (n = 25) | |

| Reflux esophagitis, n | 17 | 16 | 1 |

| Overall ST, LT, RBR (%) | 92, 60, 0 | 100, 33, 0 | 100, 0, 0 |

| Primary ST, LT, RR (%) | 100, 100, 0 | 100, 100, 0 | 0 |

| Salvage ST, LT, RR (%) | 100, 100, 0 | 100, 100, 0 | 100, 0, 0 |

| OG variceal disease, n | 13 | 11 | 2 |

| Overall ST, LT, RBR (%) | 85, 56, 38 | 91, 50, 45 | 100, 100, 0 |

| Primary ST, LT, RBR (%) | 75, 25, 75 | 66, 66, 100 | 100, 100, 0 |

| Salvage ST, LT, RBR (%) | 100, 80, 22 | 100, 80, 25 | 100, 0, 0 |

| Peptic ulcer disease, n | 49 | 34 | 12 |

| Overall ST, LT, RBR (%) | 80, 57, 34 | 80, 59, 29 | 84, 50, 31 |

| Primary ST, LT, RBR (%) | 79, 67, 21 | 81, 71, 18 | 75, 50, 25 |

| Salvage ST, LT, RBR (%) | 81, 67, 46 | 78, 40, 50 | 90, 62,3 0 |

| Angiodysplasia, -ectasia, n | 8 | 6 | 1 |

| Overall ST, LT, RBR (%) | 75, 85, 0 | 66, 80, 0 | 100, 100,0 |

| Primary ST, LT, RBR (%) | 75, 100, 0 | 75, 100, 0 | 0 |

| Salvage ST, LT, RBR (%) | 75, 75, 0 | 50, 50, 0 | 100, 100, 0 |

| Diffuse bleeding and erosions, n | 22 | 16 | 4 |

| Overall ST, LT, RBR (%) | 77, 72, 36 | 87, 84, 25 | 66, 66, 33 |

| Primary ST, LT, RBR (%) | 78, 67, 33 | 100, 100, 0 | 75, 50, 25 |

| Salvage ST, LT, RBR (%) | 66, 70, 58 | 71, 66, 57 | 100, 50, 50 |

| Cancer bleeding, n | 15 | 12 | 1 |

| Overall ST, LT, RBR (%) | 81, 85, 10 | 85, 92, 10 | 100, 100, 0 |

| Primary ST, LT, RBR (%) | 100, 100, 0 | 100, 100, 0 | 100, 100, 0 |

| Salvage ST, LT, RRB (%) | 67, 50, 0 | 67, 75, 17 | 0 |

| Other bleeding sources, n | 13 | 7 | 4 |

| Overall ST, LT, RBR (%) | 70, 70, 40 | 75, 58, 58 | 86, 75, 28 |

| Primary ST, LT, RBR (%) | 62, 60, 50 | 50, 43, 62 | 80, 67, 20 |

| Salvage ST, LT, RBR (%) | 77, 69, 36 | 100, 100, 0 | 100, 75, 30 |

For variceal bleeding, overall ST success was achieved in 91%. In oesophageal bleeding HP was used as salvage therapy in 8 patients. LT success was achieved in 3/4 (75%) patients. Re-bleeding was present in 2/7 (28.5%). In 3 patients with fundic varices bleeding, 1 LT success was achieved after applying HP as salvage therapy (33.3%). HP as a primary therapy in fundic varices bleeding is in our experience not suitable to achieve a stable hemostasis alone. In patients under therapeutic anticoagulation ST and LT success of HP were 81% and 58%, re-bleeding in 33% of patients. Regardless of whether they were applied as primary or salvage therapy or in which bleeding location, no significant differences for achieving ST or LT hemostasis and recurrence of bleeding were detected between HS and EC.

HP was applied in 17 patients with lower GI bleeding (Table 4). Among these, 9 patients were treated with HS, 7 patients with EC while in 1 patient with lower GI bleeding, both HS and EC were applied. Overall ST and LT success was 71% (12/17) and 59% (9/13), respectively with a RBR of 41%. Clinical characteristics of patients with lower GI bleeding are shown in Table 4.

| HS and EC (n = 17) | Hemospray (n = 9) | Endoclot (n = 7) | P value | |

| Sex (M) | 15 | 8 | 6 | ns |

| Age, yr | 0.007 | |||

| mean ± SD | 67.8 ± 12.2 | 72.9 ± 9.2 | 65.6 ± 9.2 | |

| range | 37-81 | 51-81 | 37-76 | |

| Application as | ns | |||

| Primary therapy | 10 (59) | 5 (55) | 4 (57.1) | |

| Salvage therapy | 7 (41.2) | 4 (44) | 3 (56) | |

| Definite therapy after HP failure | ns | |||

| Coiling | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Surgery | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 1 (14) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Coagulopathy | 3 (17.6) | 2 (22) | 1 (14) | |

| Renal insufficiency | 6 (35.3) | 3 (33) | 3 (43) | |

| Hemodialysis | 3 (17.6) | 2 (22) | 1 (14) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | 2 (11.8) | 2 (22) | 0 | |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation | 10 (59) | 3 (33) | 6 (86) | |

| Dual antiplatet therapy | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 1 (43) | |

| Vitamin K Antagonists | 3 (17.6) | 0 | 3 (43) | |

| DOAC | 3 (17.6) | 0 | 2 (29) | |

| Antiaggregation therapy | 5 (29.4) | 2 (22) | 3 (43) | |

| Short term success | 12 (79.6) | 6 (67) | 5 (71) | ns |

| Primary therapy | 7 (70) | 3/5 (60) | 3/4 (75) | |

| Salvage therapy | 5 (71.4) | 3/4 (75) | 2/3 (67) | |

| Long term success | 10 (76.9) | 6/7 (86) | 3/5 (75) | ns |

| Primary therapy | 6 (75) | 3/4(75) | 2/3 (67) | |

| Salvage therapy | 4 (57.1) | 3/3 (100) | 1/2 (50) | |

| Re-bleeding rate | 7 (41.2) | 3 (33) | 4 (57) | ns |

| Primary therapy | 3 (30) | 2/5 (40) | 1/4 (25) | |

| Salvage therapy | 4 (57.1) | 1/4 (25) | 3/3 (100) |

Herein we report on our experience in the treatment of GI bleeding both with HS and EC in a single tertiary university care center. To the best of our knowledge our work is the first to directly compare two different HP for the treatment of GI bleeding in the upper and lower GI tract. Our study confirms the findings of other investigators where an excellent immediate control of the bleeding source was achieved with HP[8,11,18,19,21]. HP exhibited an overall short-term success of 82% in our study. With this, ST success was higher in our cohort compared to a previous report on a smaller cohort by Chen and colleagues[8], although this study analyzed of success rates of HS only.

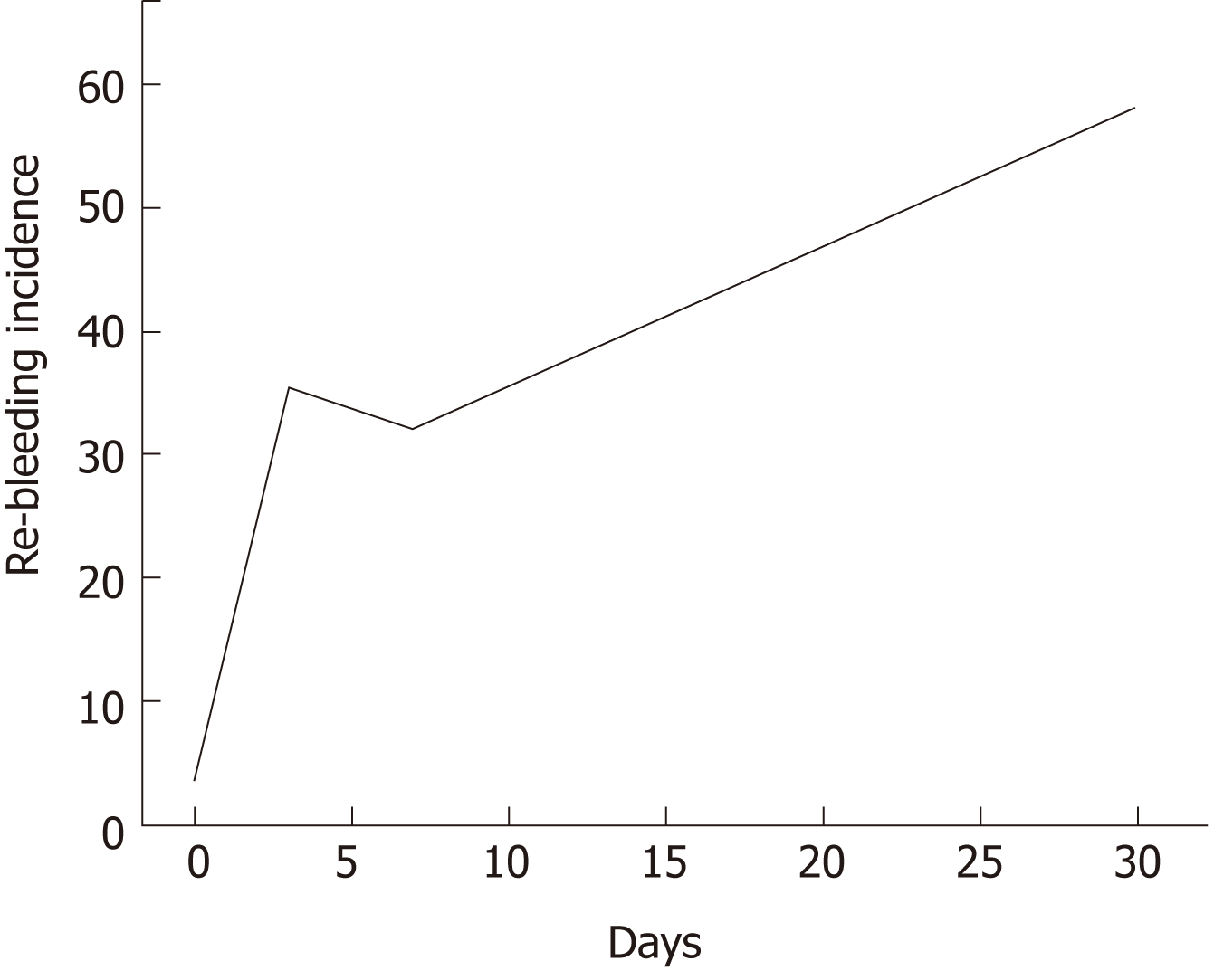

According to the literature, hemostatic success of HP within 7 to 8 d range between 51% and 87.5%[14,15,19]. Within this study, we performed FU for at least one month in the vast majority of patients (87%) and long-term success dropped to 67% in our study. Hence, these data are consistent with results from GRAPHE registry in which LT success rates of 66% were reported[19]. A graphic illustration (Figure 3) of the mean incidence of re-bleeding after application of HP according our and past studies[8-11,14-16,18,19,22] shows that RBR increase over time after HP application across studies and with this, although allowing for excellent immediate bleeding control, HP appears to be not suitable as a definitive long-term hemostasis tool in patients with a high-risk profile of bleeding recurrence. On the other hand, the benefit of HP is the high immediate hemostasis rate and that can be administered more than once without risk of “overdosing” or induction of bleeding due to mechanical irritation.

When performing subgroup analyses according to bleeding etiology, overall ST and LT success in peptic ulcer disease was 81% and 68% with a RBR of 19%. With this, our results are consistent to those reported in the literature[11,13,14,17,18,23], with immediate hemostasis ranging between 78 and 96% and RBR between 10.5 and 38%. However, when analyzing peptic ulcer disease with Forrest Ia bleeding in our study, ST and LT success were only 67% and 33% respectively. Together with results from other studies that have reported a re-bleeding risk of Forrest Ia lesions under HP between 67% and 73%[10,11,13,14,17,18,24], our data show that HP are not effective as a first-line therapy in Forrest Ia peptic ulcer bleeding. Nevertheless, HP but might still be useful in this scenario as a bridging or rescue strategy until an alternative therapy as another endoscopic procedure, a radiological embolization or surgical therapy can be performed.

HP have also been reported to be effective as rescue therapy for variceal bleeding when band ligation fails[25] and also in gastric varices and gastric bleeding derived from portal hypertension[23]. Within our study, we observed an overall ST success of 85% and LT success of 56%. It is important to note that in the majority of applications for variceal bleeding, the bleeding was serious with 70% of patients presenting with hemorrhagic shock. Against this background, the overall ST success can be regarded as high, and thus HP might represent a promising addition to arsenal of the endoscopist for severe and refractory variceal bleeding.

Due to their touch-free application and large coverage, HP are also well suited for the treatment of tumor bleeding. As shown in our study, HP provide immediate hemostatic efficacy of 95%, a short-term success of 83% and a long-term success 87% in patients with diffuse tumor bleeding. With this, our results are comparable to previous studies, in which immediate efficacy of HP and RBR ranged between 93%-100% and 20%-32%, respectively[10,14,18,21,26]. Since tumor bleeding is frequently diffuse and exhibits a large bleeding area, high RBR ranging up to 49% have been reported with conventional hemostatic approaches[24,27]. Together, with data from the largest multicenter retrospective study, in which an immediate hemostasis of HP for tumor bleeding was achieved in almost 98% of patients, our data show that HP are allow for effective control of tumor bleeding.

To date, no direct comparison between HS and EC is available. When looking across studies rates for achieving primary hemostasis in the upper GI tract with EC and HS have been reported to range between 82%-100%[13,16] and 85%-98%[8,9,11,14,15,18,19,21], respectively. Our study is the first to directly compare the efficacy of HS and EC and no significant different in their hemostatic efficacy and RBR were observed between these two agents. Nevertheless some technical differences between the two HP should be noted: first HS is sprayed at high pressure with a propellant CO2 cartridge. Such feature might be an advantage in cases of high pressure bleeding or scenarios where a large surface needs to be covered. On the other hand, high-pressure application can potentially cause further tissue injury to the point of perforation especially in friable or inflamed mucosa. Indeed, in two of the patients treated with HS (1.3%), perforation occurred as major adverse events after application of HS in the current study. Occurrence of intestinal perforation after HS application have been reported in other series as well[15,18], therefore some caution of using HS might be necessary. In contrast, with EC the pressure of spraying is much lower, allowing a more sectorial area of targeting, making EC more suitable for localized bleeding lesions like a peptic ulcers or a surface after resection. On the other hand, the area that can be covered with EC might be lower with EC as compared to HS and also high pressure bleeding might be less controlled. However, more systematic studies are clearly needed to investigate on these aspects.

For lower GI bleeding ST and LT success of HP were 75% and 56.3% with a RBR of 37.5%. Data on the role of HP for lower GI bleeding are relatively scarce to date and long-term FU data are completely lacking. In the largest series of low GI bleeding treated with EC, hemostasis was achieved in 83% of the cases with a RBR of 11%[16]. Although limited by the number of patients included in the study, our results do support the concept that HP represent valuable therapeutic options for lower GI bleeding when conventional hemostatic approaches fail.

Limitations of the current study also need to be addressed. Although our study included a large number of patients, its setting in a single high volume university centre might have led to a certain bias in terms of patients characteristics. As shown by the clinical data, a large percentage exhibited a variety of severe co-morbidities and therefore most likely do not represent an average cohort. Further, we did not utilize a randomized study protocol and the decision to apply HS or EC was at the discretion of the endoscopist and therefore subjective.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that both HPs HS and EC allow for bleeding control with high short-term efficacy when used as primary or salvage therapy. Further, both EC and HS exhibit high efficacy for achieving hemostasis in impaired coagulation status or friable tissues. With these properties, HPs represent powerful and effective additions to the armentarium of the endoscopist for treatment of GI bleeding.

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding frequently leads to hospital admission and is associated with relevant morbidity and mortality, particularly in the elderly. Due to the increasing administration of direct oral anticoagulants in the last years and the emerging role of antiplatelet agents, sufficient and effective treatment of GI bleeding is mandatory while at the same time can be clinically challenging. In the last years, endoscopists increasingly face emergency bleeding in a clinical scenario in which coagulation parameters cannot always be corrected to normal range. Further, with increasing development of advanced endoscopic therapeutic procedures, iatrogenic bleeding after endoscopic resections represents another emerging problem. For refractory cases, hemostatic powders (HP) represent “touch-free” agents.

Although data on the efficacy of Endoclot (EC) are still limited, first clinical evidences suggest that both Hemospray (HS) and EC allow for effective bleeding control. Further, no direct comparison of the efficacy of these two HP is available to date.

Against this background we set off: (1) To analyze the short and long term success in achieving hemostasis with HP; and (2) to directly compare the two agents HS and EC in their efficacy for achieving hemostasis in a large cohort of patients treated for emergency GI bleeding in our center.

Data were prospectively collected on patients who were treated with HS and EC for endoscopic hemostasis during emergency endoscopy between September 2013 and September 2017 in our center. Patients were followed-up for at least one month after index endoscopy and data analysis was performed after follow-up was completed

HP was applied in 154 consecutive patients (mean age 67 years) with GI bleeding in our center. Patients were followed up for at least 1 month (mean follow up: 3.2 mo). The majority of HP applications were in the upper GI tract (89%) with the following bleeding sources: Peptic ulcer disease (35%), esophageal varices (7%), tumor bleeding (11.7%), reflux esophagitis (8.7%), diffuse oozing bleeding and erosions (15.3%). Overall short term (ST) success with HP was achieved in 125 patients (81%) and long term (LT) success in 81 patients (67%). Re-bleeding occurred in 27% of all patients treated with HP. In 72 patients (47%), HP was applied as a salvage hemostatic therapy, here ST and LT success were 81% and 64%, respectively, with re-bleeding in 32% of patients. As a primary hemostatic therapy, ST and LT success were 82% and 69%, respectively, with re-bleeding occurring in 22%. Subgroup analysis showed a ST and LT efficacy for cancer bleeding of 83% and 87%, for peptic ulcer disease of 81% and 56% and in patients under therapeutic anticoagulation of 80% and 60.5%. There was no statistical difference in the ST or LT efficacy between EC and HS for the various indications; however, HS was more frequently applied for upper GI bleeding (P = 0.04)

Within this study, we retrospectively analyzed the hemostatic efficacy of HPs HS and EC as first line or salvage therapy in several clinical scenarios in a large cohort of prospectively included patients. As shown in our report, both HPs allow for excellent ST bleeding control when applied as primary or salvage therapy. At the same time, LT efficacy over a period of 4 weeks is maintained in a considerable amount of patients.

Both EC and HS exhibit high efficacy for achieving hemostasis in impaired coagulation status or friable tissues. With these properties, HPs represent powerful and effective additions to the armentarium of the endoscopist for treatment of GI bleeding.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Bortoli N, Hoff DAL, Nalbant S S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Polo-Tomás M, Ponce M, Alonso-Abreu I, Perez-Aisa MA, Perez-Gisbert J, Bujanda L, Castro M, Muñoz M, Rodrigo L, Calvet X, Del-Pino D, Garcia S. Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1633-1641. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Hearnshaw SA, Logan RF, Lowe D, Travis SP, Murphy MF, Palmer KR. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut. 2011;60:1327-1335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Button LA, Roberts SE, Evans PA, Goldacre MJ, Akbari A, Dsilva R, Macey S, Williams JG. Hospitalized incidence and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999 to 2007: a record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:64-76. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Holster IL, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ETTL. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:105-112.e15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Harvey L, Holley CT, John R. Gastrointestinal bleed after left ventricular assist device implantation: incidence, management, and prevention. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;3:475-479. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans J, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fisher L, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Dominitz JA, Cash BD. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:707-718. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Gralnek IM, Barkun AN, Bardou M. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:928-937. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Chen YI, Barkun A, Nolan S. Hemostatic powder TC-325 in the management of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a two-year experience at a single institution. Endoscopy. 2015;47:167-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Holster IL, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. Hemospray in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients on antithrombotic therapy. Endoscopy. 2013;45:63-66. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Sung JJ, Luo D, Wu JC, Ching JY, Chan FK, Lau JY, Mack S, Ducharme R, Okolo P, Canto M, Kalloo A, Giday SA. Early clinical experience of the safety and effectiveness of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:291-295. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Smith LA, Stanley AJ, Bergman JJ, Kiesslich R, Hoffman A, Tjwa ET, Kuipers EJ, von Holstein CS, Oberg S, Brullet E, Schmidt PN, Iqbal T, Mangiavillano B, Masci E, Prat F, Morris AJ. Hemospray application in nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of the Survey to Evaluate the Application of Hemospray in the Luminal Tract. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:e89-e92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Holster IL, van Beusekom HM, Kuipers EJ, Leebeek FW, de Maat MP, Tjwa ET. Effects of a hemostatic powder hemospray on coagulation and clot formation. Endoscopy. 2015;47:638-645. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Beg S, Al-Bakir I, Bhuva M, Patel J, Fullard M, Leahy A. Early clinical experience of the safety and efficacy of EndoClot in the management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E605-E609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Sulz MC, Frei R, Meyenberger C, Bauerfeind P, Semadeni GM, Gubler C. Routine use of Hemospray for gastrointestinal bleeding: prospective two-center experience in Switzerland. Endoscopy. 2014;46:619-624. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Yau AH, Ou G, Galorport C, Amar J, Bressler B, Donnellan F, Ko HH, Lam E, Enns RA. Safety and efficacy of Hemospray® in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:72-76. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Prei JC, Barmeyer C, Bürgel N, Daum S, Epple HJ, Günther U, Maul J, Siegmund B, Schumann M, Tröger H, Stroux A, Adler A, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Jürgensen C, Wentrup R, Wiedenmann B, Binkau J, Hartmann D, Nötzel E, Domagk D, Wacke W, Wahnschaffe U, Bojarski C. EndoClot Polysaccharide Hemostatic System in Nonvariceal Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Observational Pilot Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:e95-e100. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Holster IL, Brullet E, Kuipers EJ, Campo R, Fernández-Atutxa A, Tjwa ET. Hemospray treatment is effective for lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2014;46:75-78. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Hagel AF, Albrecht H, Nägel A, Vitali F, Vetter M, Dauth C, Neurath MF, Raithel M. The Application of Hemospray in Gastrointestinal Bleeding during Emergency Endoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:3083481. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Haddara S, Jacques J, Lecleire S, Branche J, Leblanc S, Le Baleur Y, Privat J, Heyries L, Bichard P, Granval P, Chaput U, Koch S, Levy J, Godart B, Charachon A, Bourgaux JF, Metivier-Cesbron E, Chabrun E, Quentin V, Perrot B, Vanbiervliet G, Coron E. A novel hemostatic powder for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter study (the "GRAPHE" registry). Endoscopy. 2016;48:1084-1095. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Park JC, Kim YJ, Kim EH, Lee J, Yang HS, Kim EH, Hahn KY, Shin SK, Lee SK, Lee YC. Effectiveness of the polysaccharide hemostatic powder in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Using propensity score matching. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1500-1506. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Cahyadi O, Bauder M, Meier B, Caca K, Schmidt A. Effectiveness of TC-325 (Hemospray) for treatment of diffuse or refractory upper gastrointestinal bleeding - a single center experience. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E1159-E1164. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Smith LA, Morris AJ, Stanley AJ. The use of hemospray in portal hypertensive bleeding; a case series. J Hepatol. 2014;60:457-460. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Sheibani S, Kim JJ, Chen B, Park S, Saberi B, Keyashian K, Buxbaum J, Laine L. Natural history of acute upper GI bleeding due to tumours: short-term success and long-term recurrence with or without endoscopic therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:144-150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Ibrahim M, El-Mikkawy A, Abdalla H, Mostafa I, Devière J. Management of acute variceal bleeding using hemostatic powder. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:277-283. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Leblanc S, Vienne A, Dhooge M, Coriat R, Chaussade S, Prat F. Early experience with a novel hemostatic powder used to treat upper GI bleeding related to malignancies or after therapeutic interventions (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:169-175. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Kim YI, Choi IJ, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Kim MJ, Ryu KW, Kim YW, Park YI. Outcome of endoscopic therapy for cancer bleeding in patients with unresectable gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1489-1495. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |