Published online Feb 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.772

Revised: June 9, 2005

Accepted: July 8, 2005

Published online: February 7, 2006

AIM: Since 1987, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has been widely used as the favored treatment for gallbladder lesions. Cholecystoenteric fistula (CF) is an uncommon complication of the gallbladder disease, which has been one of the reasons for the conversion from LC to open cholecystectomy. Here, we have reported four cases of CF managed successfully by laparoscopic approach without conversion to open cholecystectomy.

METHODS: During the 4-year period from 2000 to 2004, the medical records of the four patients with CF treated successfully with laparoscopic management at the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital-Taipei were retrospectively reviewed.

RESULTS: The study comprised two male and two female patients with ages ranging from 36 to 74 years (median: 53.5 years). All the four patients had right upper quadrant pain. Two of the four patients were detected with pneumobilia by abdominal ultrasonography. One patient was diagnosed with cholecystocolic fistula preoperatively correctly by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and the other one was diagnosed as cholecystoduodenal fistula by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Correct preoperative diagnosis of CF was made in two of the four patients with 50% preoperative diagnostic rate. All the four patients underwent LC and closure of the fistula was carried out by using Endo-GIA successfully with uneventful postoperative courses. The hospital stay of the four patients ranged from 7 to 10 d (median, 8 d).

CONCLUSION: CF is a known complication of chronic gallbladder disease that is traditionally considered as a contraindication to LC. Correct preoperative diagnosis of CF demands high index of suspicion and determines the success of laparoscopic management for the subset of patients. The difficult laparoscopic repair is safe and effective in the experienced hands of laparoscopic surgeons.

- Citation: Wang WK, Yeh CN, Jan YY. Successful laparoscopic management for cholecystoenteric fistula. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(5): 772-775

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i5/772.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.772

Since 1987, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has been the favored treatment for gallbladder lesions[1]. With experience gained from laparoscopic surgery, LC has successfully been attempted in every kind of gallbladder disease.

Cholecystoenteric fistula (CF) is an uncommon disease affecting both biliary and the gastrointestinal tracts, with reported incidences ranging from 0.15% to 5% of biliary disease[2]. Chronic cholecystitis with gallstones is the primary etiology in as many as 75% of CF patients. Cholecystoduodenal type accounts for as many as 80% of CF[3]. CF is generally considered to be a relative contraindication to LC because of the difficulties involved in its management intraoperatively[4]. Laparoscopic stapling techniques have been reported as feasible and safe methods for treating such fistula[2,3,5-7]; however, these procedures are not always performed successfully. We have reported four cases of CF managed successfully by laparoscopic approach due to the correct preoperative diagnosis and experienced laparoscopic techniques.

From January 2000 to December 2003, 4 131 patients underwent LC for gallbladder lesions at the Department of General Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan), 4 (0.1%) of them were identified as having CF. CF was defined as an abnormal communication between gallbladder and the neighboring organ. This study retrospectively reviewed the medical records of these four patients. All the patients’ history was recorded and underwent physical examination, ultrasonography (USG), or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), or computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram (MRCP) to establish a preoperative diagnosis. Preoperative ERCP was done routinely in patients with a history of jaundice, cholangitis or pancreatitis, patients with dilated common bile duct (CBD) displayed on abdominal USG, and patients with abnormal liver function tests. Patients with CBD stones had the stones removed endoscopically before LC. Moreover, endoscopic papillotomy (EPT) with stone retrieval and/or endonasobiliary drainage (ENBD) was performed to relieve fever, jaundice, and/or CBD stone retrieval. Data were collected on patients’ age, sex, preoperative diagnoses, operative findings, operative methods, morbidity, and management.

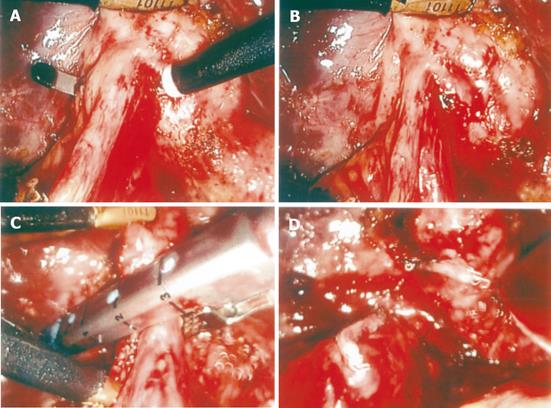

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia using the standard four-cannula technique. The cystic artery generally was first controlled using metallic clips and divided. Moreover, the fistula was cleaned until the anatomy was clear and adequate space existed to apply an Endo-GIA (US Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT, USA). Endo-GIA was applied via the epigastric port and then was applied to the adjacent organ end of the fistula using an applicator (Ethicon Endo-surgery). One of the blades of the Endo-GIA with the locking mechanism at its end must be seen clearly behind the fistula tract and the locking mechanism should be free of the intervening tissue to facilitate and ensure Endo-GIA locking. The gallbladder end of the fistula was ligated and simultaneously the fistula was divided (Figures 1A-1D). The gallbladder was dissected from the liver using electrocautery and removed via the umbilical or epigastric wound with an endo-bag. The postoperative course and complications were recorded. Patients were followed up in the outpatient clinic one month after the surgery and at three-monthly intervals for one year. Patients who operated more than one year before were interviewed by telephone to identify any unrecorded complications before the conclusion of the study (2004, June).

The study comprised two male and two female patients with ages ranging from 36 to 74 years (median: 53.5 years, Table 1). All the four patients exhibited right upper quadrant pain. Table 1 summarizes the laboratory data of these four patients. All the four patients revealed anemia and leukocytosis. Only one patient revealed elevated bilirubin level due to common bile duct stone and cholangitis.

| Patients | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Age (yr) | 63 | 74 | 36 | 44 |

| Gender | F | M | M | F |

| Symptoms and signs | RUQ pain | RUQ pain, fever, and jaundice | RUQ pain | RUQ pain |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7.9 | 9.7 | 8.2 | 9.5 |

| WBC (1 000/dL) | 11.4 | 14.3 | 14.1 | 13.5 |

| Bilirubin (T) (mg/dL) | 0.8 | 8.3 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| AST (IU/L) | 20 | 339 | 17 | 51 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 15 | 319 | 30 | 62 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 347 | 182 | 74 | 82 |

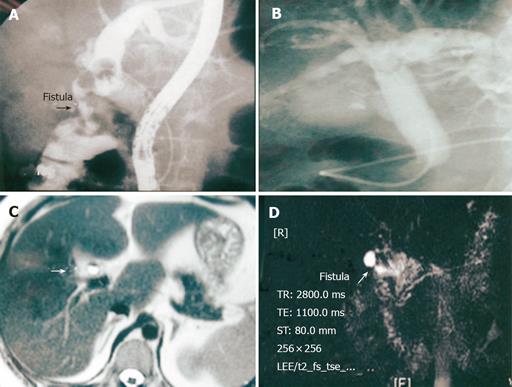

Table 2 displays the preoperative investigations, diagnoses, managements, and operative outcomes. Two of the four patients were detected as gallbladder stone with pneumobilia by abdominal USG. One patient had gallbladder stone and a cholecystocolic fistula displayed by ERCP (patient 1, Figure 2A). ERCP revealed opacification of the gallbladder and abnormal fistula communication with colon demonstrated by haustration. The other one had pneumobilia revealed by ERCP (patient 2, Figure 2B). MRCP diagnosed cholecystoduodenal fistula in one patient as demonstrated by air-fluid level and abnormal communication between gallbladder and duodenum in T2-weighed image (patient 4, Figures 2C and 2D). Correct preoperative diagnosis of CF was made in two of the four patients with 50% preoperative diagnostic rate. Operative findings revealed two cholecystoduodenal fistula (patients 2 and 4), one cholecystocolic fistula (patient 1), and one cholecystocholedochal fistula (Mirizzi syndrome type II, patient 3). All the four patients underwent LC and closure of the fistula by Endo-GIA (after successful identification of the fistula). None of the patients needed to be converted to open cholecystectomy and all the four patients had uneventful postoperative course. None of the CF was caused by malignancy. The hospital stay of the four patients ranged from 7 to 10 d (median, 8 d). Length of follow-up ranged from 8 to 48 mo (median, 36.5 mo).

| Patients | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| USG | GB stone, pneumobilia, and CBD stone | GB stone and biliary tree dilatation | Contracted GB with stone and biliary tree dilatation | GB stone and pneumobilia |

| ERCP/EPT/stone retrieval | + (fistula)/+/+ | + (pneumobilia)/+/+ | +/–/– | –/–/– |

| CT/MRCP | –/– | –/– | –/– | –/+ (fistula) |

| Preoperative diagnosis | Cholecystocolic fistula | GB stone and CBD stone | Cystic duct stone and normal bile duct | Cholecystoduodenal fistula |

| Associate biliary lesion | GB stone and CBD stone | GB stone and CBD stone | GB stone | GB stone |

| Operative findings | Cholecystocolic fistula | Cholecystoduodenal fistula | Cholecystocholedochal fistula (Mirizzi syndrome type II) | Cholecystoduodenal fistula |

| Operative method | LC and closure of fistula using Endo-GIA | LC and closure of fistula using Endo-GIA | LC and closure of fistula using Endo-GIA | LC and closure of fistula using Endo-GIA |

| Cause of conversion | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Morbidity | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Hospital stay (d) | 8 | 8 | 7 | 10 |

As we know, the development of a fistulous tract from the gallbladder is associated with gallstones in 90% of cases. Our study demonstrated CF was associated with gallstones in 100% cases. As seen in this study, patients with a biliary-enteric fistula are commonly presented with signs and symptoms similar to those of chronic cholecystitis. These lack specific symptoms that suggest the presence or development of a biliary-intestinal fistula. Right upper quadrant pain was present in all the CF patients, irrespective of the level of the fistula. Yamashita et al [8] reviewed 33 (1.3%) of 1 929 consecutive patients who had been treated for biliary tract diseases during a 12-year period had biliary fistulas. In this study, we found that the incidence of CF was only 0.1%, showing a decreased incidence these years in Asia corresponding to Western observations. CF is generally considered to be a relative contraindication to LC because of the difficulties involved in its management intraoperatively, and CF is therefore usually managed by laparotomy. This may partly explain the reason of lower incidence in this series.

Preoperative findings can be suggestive of internal biliary fistula. Pneumobilia with an atrophic gallbladder adherent to neighboring organs seen on CT scanning or USG is highly suggestive of the presence of cholecystoenteric fistula, as seen in patients 1 and 4[4]. However, the reliability of a diagnosis based on the presence or absence of pneumobilia has been questioned. Similar to the report by Yamashita et al [8], ERCP was the most valuable diagnostic method for revealing the presence of biliary-enteric fistula. As seen in the patient 1, ERCP could be used to diagnose the cholecystocolic fistula by demonstration of the haustration of the colon. In this study, we were able to diagnose biliary-enteric fistula preoperatively by USG, ERCP, or MRCP, and could therefore decide on a treatment strategy preoperatively. Besides, MRCP provides another reliable diagnostic tool to clearly demonstrate the abnormal communication, especially in T2-weighed image. However, only 50% of CF was diagnosed preoperatively in our series.

Treatment advocated for CF is cholecystectomy and closure of the fistula communication. Making a knot either intracorporeally or extracorporeally is time-consuming and cannot secure this difficult fistula closure. An alternative is applying laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing interruptedly or continuously with absorbable or non-absorbable material to close the inflammatory fistula, as performed in the open procedure. However, this method is technically demanding and time-consuming[5]. Ligation of the fistula with an endoloop offers a solution to the problem. The technique for the application of an endoloop consists of dividing the fistula and then applying the endoloop. This becomes more difficult if, after the fistula is divided, loss of traction on the communicating organ results in retraction of the divided fistula stump outside of the laparoscopic field of view. Although endoloop is cheaper than Endo-GIA, some new devices are needed to apply to avoid this difficulty[9]. Endo-GIA is easy to use and effective. However, the following important safety points must be noted. First, the fistula must be cleaned until the anatomy of the abnormal communication is clear and adequate space exists to apply an Endo-GIA. Second, one of the blades of the Endo-GIA with the locking mechanism at its end must be seen clearly behind the communicating organ and the locking mechanism should be free of the intervening tissue to ensure successful Endo-GIA locking. The above ensures safe closure of the fistula tract with the communicating organ. Especially, when resecting the fistula laparoscopically, it is important to ensure that part of the colonic wall is included in the excised specimen. Two reasons explain the maneuver, including that histological examination is essential to rule out colonic carcinoma at the site of fistula and unhealthy fistula or gallbladder tissue, if left on the wall of the colon, can become ischemic at a later date, thereby subsequently leading to the perforation of the wall[6]. However, no malignancy was seen in the colonic wall of the cholecystocolonic fistula in this study.

In conclusion, this report shows that with increasing experience and confidence, contraindications to laparoscopic cholecystectomy are diminishing. Laparoscopic management of CF with Endo-GIA is feasible and safe, if CF is diagnosed correctly preoperatively and managed by experienced laparoscopic surgeons.

S- Editor Kumar M and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Cao L

| 1. | Cuschieri A, Dubois F, Mouiel J, Mouret P, Becker H, Buess G, Trede M, Troidl H. The European experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1991;161:385-387. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 611] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 630] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Angrisani L, Corcione F, Tartaglia A, Tricarico A, Rendano F, Vincenti R, Lorenzo M, Aiello A, Bardi U, Bruni D. Cholecystoenteric fistula (CF) is not a contraindication for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1038-1041. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharma A, Sullivan M, English H, Foley R. Laparoscopic repair of cholecystoduodenal fistulae. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:433-435. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Macintyre IM, Wilson RG. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1993;80:552-559. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yeh CN, Jan YY, Liu NJ, Yeh TS, Chen MF. Endo-GIA for ligation of dilated cystic duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an alternative, novel, and easy method. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:153-157. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martin I, Siriwardena A. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the presence of a cholecysto-enteric fistula. Dig Surg. 2000;17:178-180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Prasad A, Foley RJ. Laparoscopic management of cholecystocolic fistula. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1789-1790. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yamashita H, Chijiiwa K, Ogawa Y, Kuroki S, Tanaka M. The internal biliary fistula--reappraisal of incidence, type, diagnosis and management of 33 consecutive cases. HPB Surg. 1997;10:143-147. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nowzaradan Y, Meador J, Westmoreland J. Laparoscopic management of enlarged cystic duct. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992;2:323-326. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |