Published online Jul 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3498

Revised: June 12, 2009

Accepted: June 19, 2009

Published online: July 28, 2009

AIM: To assess gallbladder emptying and its association with cholecystitis and abdominal pain in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

METHODS: Twenty patients with PSC and ten healthy subjects were investigated. Gallbladder fasting volume, ejection fraction and residual volume after ingestion of a test meal were compared in patients with PSC and healthy controls using magnetic resonance imaging. Symptoms, thickness and contrast enhancement of the gallbladder wall and the presence of cystic duct strictures were also assessed.

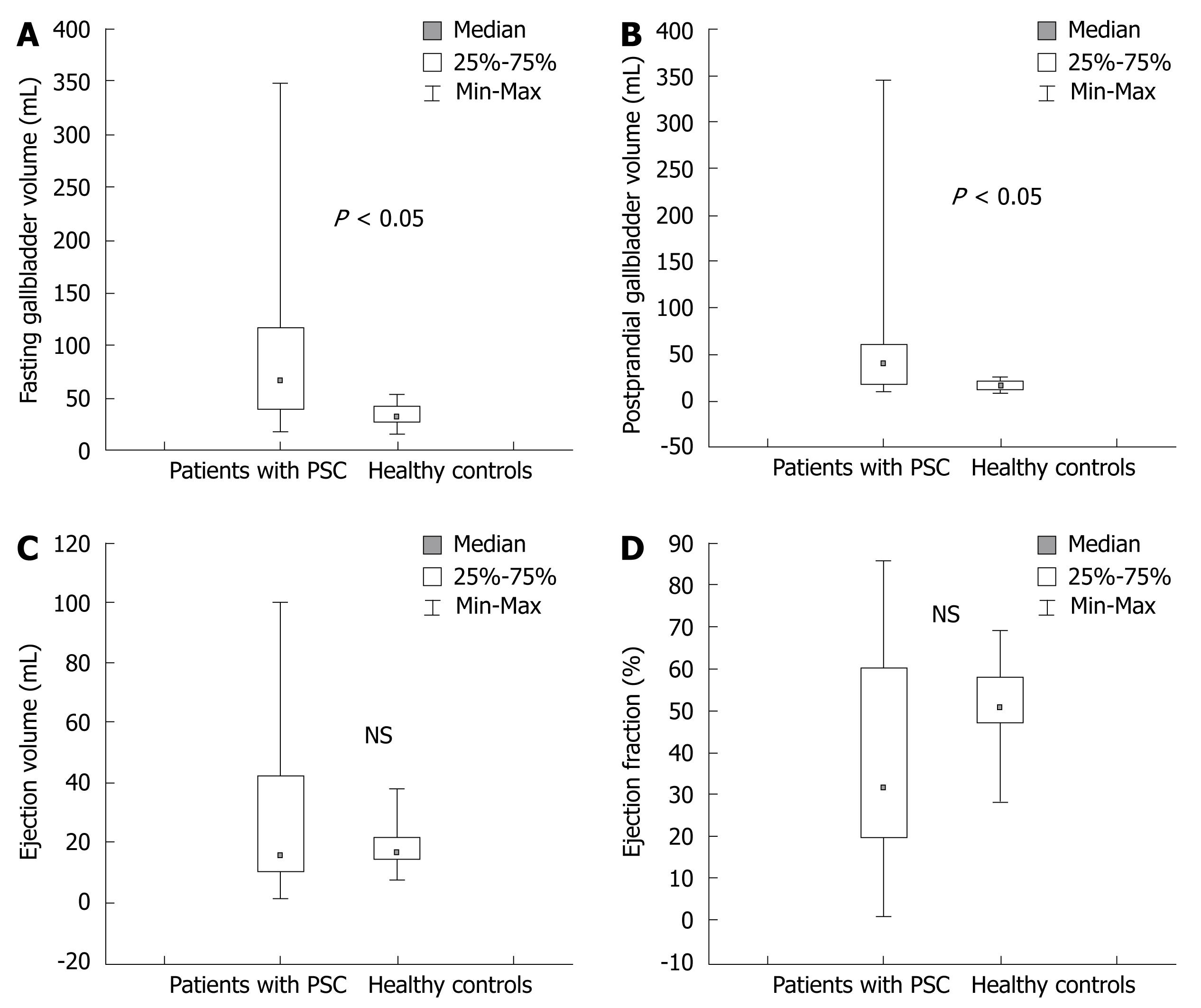

RESULTS: Median fasting gallbladder volume in patients with PSC [67 (19-348) mL] was twice that in healthy controls [32 (16-55) mL] (P < 0.05). The median postprandial gallbladder volume in patients with PSC was significantly larger than that in healthy controls (P < 0.05). There was no difference in ejection fraction, gallbladder emptying volume or mean thickness of the gallbladder wall between PSC patients and controls. Contrast enhancement of the gallbladder wall in PSC patients was higher than that in controls; (69% ± 32%) and (42% ± 21%) (P < 0.05). No significant association was found between the gallbladder volumes and occurrence of abdominal pain in patients and controls.

CONCLUSION: Patients with PSC have increased fasting gallbladder volume. Gallbladder Mucosal dysfunction secondary to chronic cholecystitis, may be a possible mechanism for increased gallbladder.

- Citation: Said K, Edsborg N, Albiin N, Bergquist A. Gallbladder emptying in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(28): 3498-3503

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i28/3498.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3498

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is an idiopathic chronic cholestatic inflammatory liver disease characterized by diffuse fibrosing inflammation of intra- and/or extrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in bile duct obliteration, biliary cirrhosis, and eventually hepatic failure[12]. Gallbladder abnormalities, including gallstones, cholecystitis and gallbladder masses are common in patients with PSC[34], and seems to be part of the spectrum of the disease. Inflammation of the bile ducts in PSC is similar to that found in the gallbladder epithelium in these patients.

Functional impairment of the gallbladder in PSC is rarely studied. Van de Meeberg et al[5] showed enlarged fasting gallbladder volumes and increased postprandial volumes in patients with PSC compared with patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and healthy controls, although the ejection fraction of bile was normal. Other studies in patients with PSC have not found gallbladder enlargement[67]. Increased gallbladder volume or gallbladder retention are known to occur in conditions other than PSC such as truncal vagotomy[89], chronic pancreatitis[10], octreotide therapy[11], obesity[12], diabetes mellitus[13], pregnancy[14] and distal biliary obstruction[15]. PSC associated inflammation of the gallbladder epithelium and cholangiographic abnormalities of the cystic duct have been reported in patients with PSC[3716].

One of the most common symptoms at the time of presentation of PSC is mild to severe abdominal pain localized in the right upper quadrant[17–20]. The cause of abdominal pain is unclear, it seems, however, unrelated to the grade of bile duct strictures. In addition, cholecystectomy seldom improves abdominal pain in these patients. A possible association between enlarged fasting gallbladder volume, ejection fraction and abdominal pain has never been investigated in patients with PSC.

The primary aim of the present study, using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), was to evaluate the fasting and postprandial gallbladder volumes and to assess whether or not gallbladder emptying is associated with abdominal pain in patients with PSC. Secondly, we studied if the presence of imaging signs of chronic cholecystitis is correlated to gallbladder volume, the emptying process or abdominal pain.

The study was approved by the Ethics committee at Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge and written informed consent was received from all patients and controls.

Twenty patients, (14 men and 6 women) who ranged in age from 24 to 59 years (mean age 39 ± 10 years), with well-defined PSC[21] treated at the Liver Unit, Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge were included in the study between January 2005 and July 2006. Clinical data were obtained by review of the complete medical history collected from patient files. Patients with hepatobiliary malignancy, diabetes mellitus, chronic pancreatitis or distal biliary obstruction (dominant extrahepatic strictures) were excluded. Ten healthy subjects (5 men and 5 women), who ranged in age from 31-79 years (mean age 47 ± 13.5 years), without any history of gastrointestinal disease or previous abdominal surgery served as controls. Informed consent for study participation was received from all patients and controls.

After overnight fasting, two intravenous cannulas were inserted into the antecubital veins: one for blood sampling and one for intravenous injection of a contrast agent for MRI. The fasting gallbladder volume was analysed by MRI, prior to injection of the contrast agent, time = 0 min. One hour later (time = 1 h) a test meal consisting of 200 g “Swedish hash” (fried diced meat, onions and potatoes served with beetroot), 250 mL milk (3% fat) and an apple, totalling 2064 kJ including 21 g fat was ingested. Postprandial gallbladder volume and ejection fraction were obtained at 2.5 h (time = 2.5 h), that is an hour and a half after ingestion of the fat-meal at which point gallbladder contraction is supposed to be maximal[522–24].

Biochemical variables including alkaline phosphatase, serum transaminases, total bilirubin, International normalized ratio (INR), serum albumin and CRP were obtained at the beginning of the procedure and analysed using standard procedures at the Karolinska University Hospital.

Every subject filled in a questionnaire for the assessment of abdominal pain localized in the right upper quadrant, abdominal discomfort and nausea, before the first MRI, just before, and one and three hours after meal ingestion. The questionnaire consisted of visual analogue scales (VAS) where the patient marked the degree of symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea and abdominal discomfort.

Examinations including the gallbladder and the hepatobiliary system were performed (after overnight fasting) using a 1.5 T magnetic resonance system [Magnetom Symphony (n = 1 PSC), Vision (n = 7 PSC) or Avanto (n = 12 PSC and 10 controls]; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany]. Each patient was examined using the same unit before and after the meal combining the spine and the flexible body array coil. The use of different units was therefore not considered to influence the results. Gd-BOPTA (MultiHance® 0.5 mmol/mL, Bracco, Milan, Italy) at a dosage of 0.1 mmol/kg of was injected. Axial breath-hold 3D-T1-weighted scans (VIBE, slice thickness 1.7-2.5 mm) were performed natively and dynamically in arterial, portal-venous and delayed 5 min phase for clinical diagnosis. Postprandially, in the hepatobiliary phase, the hepatobiliary system was rescanned (VIBE).

The thickness of the gallbladder wall was measured on the axial T2 Haste slices at three different areas of the gallbladder. The mean values of the measurements were calculated for each patient. The presence of biliary stones and perivesical fluid was noted and the cystic duct was evaluated for the presence of strictures. Cystic duct abnormalities were defined as mural irregularities of the cystic duct on magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC).

Contrast enhancement of the gallbladder wall was analyzed in % using the formula: Contrast enhancement = [SI (portalvenousphase) - SI (native)]/SI (native) × 100.

In each patient the signal intensity (SI) of the wall was measured, in a single voxel, in three different areas, trying to avoid vessels and adjacent intestinal loops or the liver parenchyma. The same areas were measured natively and in the portal venous phase and the enhancement was calculated for each part. The mean of the measurements was calculated for each patient.

The 3D-T1-weighted scans were analysed using a Voxar® 3D workstation (Barco NV, Kortrijk, Belgium) using 3D segmentation and volume measurements. The volume of the gallbladder was measured fasting (delayed 5 min phase) and in the postprandial phase. In the latter hepatobiliary phase, contrast filling of the gallbladder was also noted. The analyses were made in consensus by two radiologists (NE and NA).

The ejection volume was measured in microliter using the formula: Ejection volume = volume (fasting) - volume (postprandial).

The ejection fraction or gallbladder emptying was measured in % using the formula: Ejection fraction = [volume (fasting) - volume (postprandial)]/volume (fasting) × 100.

Gallbladder fasting volume, ejection fraction and postprandial gallbladder volume of patients with PSC were compared with healthy controls. Postprandial gallbladder refilling of bile (that is, of contrast excreted to the common bile duct) was noted.

Data were analyzed using statistical software (v 7.0, Stat Soft Inc.). Values are expressed as mean and standard deviation or as median (range). For comparison of categorical data, the Chi-square test was used, or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Spearman’s correlation test was used to determine the association between contrast enhancement and gallbladder wall thickness. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

The clinical characteristics of the 20 PSC patients and the healthy controls are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding age and body mass index (BMI). The mean levels of plasma alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and plasma bilirubin were significantly higher in patients with PSC than in the healthy controls.

| Clinical characteristic | PSC patients (n = 20) | Healthy controls (n = 10) | P value |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 70% (14/20) | 50% (5/10) | NS |

| Female | 30% (6/20) | 50% (5/10) | NS |

| Age in years (± SD) | 39 ± 10 | 47 ± 13 | NS |

| Associated IBD | 90% (18/20) | 0 | |

| UC | 85% (17/20) | ||

| CD | 5% (1/20) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 10% (2/20) | 0 | |

| Treatment with UDCA | 85% (17/20) | 0 | |

| Cholangiographic distribution of PSC | - | ||

| Extra-and intrahepatic involvement | 75% (15/20) | ||

| Intrahepatic changes | 25% (5/20) | ||

| Duration of PSC in years | 9.7 ± 5 | - | |

| Mean P-ALP (< 1.9 &mgr;kat/L) | 7 ± 6 | 1 ± 0.3 | P < 0.05 |

| Mean P-ALT (< 0.76 &mgr;kat/L) | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | P < 0.05 |

| Mean P-Bilirubin (< 26 &mgr;mol/L) | 20 ± 14 | 10 ± 5 | NS |

| Mean P-Albumin (36-45 g/L) | 40 ± 6 | 39 ± 5 | NS |

| Mean P-Cholesterol (3.9-7.8 mmol/L) | 5 ± 01 | 5 ± 0.1 | NS |

| Mean BMI | |||

| Male | 25 ± 4 | 25 ± 2 | NS |

| Female | 25.5 ± 2.5 | 25 ± 5 | NS |

The median fasting gallbladder volume in patients with PSC was twice that of the healthy controls; 67 (range 19-348) mL and 32 (range 16-55) mL, respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). The mean fasting gallbladder volume (mean ± SD) in patients with PSC was 91 ± 78 mL compared with 35 ± 11 mL in healthy controls. The median postprandial gallbladder volume in patients with PSC was significantly higher than that in healthy controls; 40 (9-345) mL and 16 (9-26) mL, respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 1B). Median ejection volume was 16 (1-100) mL in PSC patients and 16 (8-38) mL in healthy controls (n.s.) (Figure 1C).

There was no significant difference in ejection fraction between PSC patients and controls as shown in Figure 1D. Ninety percent (18/20) of patients had inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and two of these patients had active disease. We found no significant difference in gallbladder volumes between the PSC patients with active IBD and patients who were in remission. None of the women in the PSC group were pregnant at the time of the study.

Two of the patients with PSC had liver cirrhosis. One of them, a 42-year-old man had the largest fasting gallbladder volume (348 mL) with an ejection fraction of only 1% (Figure 2). The other cirrhotic patient was a 37-year-old man with a fasting gallbladder volume of 20 mL and an ejection fraction of 55%.

Gallstones were found in the gallbladder in 20% (4/20) of the PSC patients but not in the controls. The median gallstone size was 2.5 mm (2-6 mm), these gallstones had no impact in the cystic duct in preprandial images. None of the patients had visible stones in the common bile duct. Perivesical fluid was seen in small amounts in 20% (4/20) of the PSC patients. None of the patients had a previous history of pancreatitis and we found no significant difference in gallbladder size between patients with and without abdominal pain.

The thickness of the gallbladder wall (mean ± SD) did not differ significantly between PSC patients and controls; 2.2 ± 0.5 mm and 1.9 ± 0.3 mm, respectively. However, there was a significant increase in contrast enhancement of the gallbladder wall (mean ± SD) in PSC patients compared to controls; 69% ± 32% and 43% ± 21%, respectively (P < 0.05). There were no other signs of acute cholecystitis.

In all subjects there was a significant correlation between high contrast enhancement of the gallbladder wall and large gallbladder volume at fasting (P < 0.05) (r = 0.39). Postprandial gallbladder volume and ejection fraction were not significantly correlated to contrast enhancement of the gallbladder wall.

We found no correlation between patients with increased gallbladder volume, increased postprandial gallbladder volume and decreased ejection fraction and levels of P-Bilirubin, P-Cholesterol, P-Albumin, P-ALP, duration and distribution of PSC, treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), presence of IBD or age. In all subjects there was no significant correlation between BMI and fasting gallbladder volume or ejection fraction of the gallbladder. Seventeen of 20 patients with PSC were taking 10-15 mg/kg per day of UDCA.The fasting gallbladder volume and ejection fraction was similar in patients who were on UDCA treatment (96 ± 83 mL and 38% ± 27%) and patients who were not treated with UDCA (57 ± 19 mL and 36% ± 15%) (n.s.). Seventy five percent (15/20) of the PSC patients and 100% (10/10) of the healthy controls showed contrast in the gallbladder in the hepatobiliary phase (n.s.). Abnormalities of the cystic ducts were visualized in 13 (60%) of the PSC patients and in none in the control group. No significant correlation was found between increased gallbladder fasting volume, decreased ejection fraction or lack of postprandial gallbladder refilling and presence of abnormalities in the cystic ducts.

No significant association was found between gallbladder volumes or contrast enhancement and occurrence of abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort and nausea in PSC patients and controls. Before the fatty meal, 25% of PSC patients experienced abdominal pain, the visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 1 to 4. Twenty five percent of PSC patients experienced nausea with the VAS ranging from 1 to 2. Twenty percent of PSC patients experienced abdominal discomfort with the VAS ranging from 1 to 4. There was no significant increase in symptoms in the PSC group at one or three hours after meal ingestion. None of the healthy controls experienced symptoms pre- and postprandially.

In the present study, we showed that patients with PSC have a significant increase in gallbladder volume both pre- and postprandially compared with healthy control subjects. This is in agreement with a previous sonographic study by van de Meeberg et al[5], who reported a fasting gallbladder volume of 73 ± 13.7 mL compared with 91 ± 77.9 mL in our study. The reason for the increased fasting gallbladder volume in patients with PSC is unclear. Several mechanisms may cause gallbladder enlargement, for example obstruction of the cystic duct or the common bile duct distal to the cystic duct, gallbladder dysmotility or gallbladder mucosal dysfunction may all contribute to increased fasting gallbladder volumes. In our study we excluded patients with significant extrahepatic strictures. Seventy-five percent of the PSC patients showed contrast in the gallbladder indicating the absence of a dominant stricture in the cystic duct. We also found that the gallbladder ejection fraction in PSC patients was similar to that of the healthy controls. Taken together, these findings do not suggest mechanical obstruction and/or gallbladder dysmotility as reasons for the enlarged gallbladder fasting volume in these patients.

Gallbladder abnormalities are common in PSC, and include cholecystitis which is found in 25% of all PSC patients[4]. In experimental cholecystitis the process of fluid absorption in the gallbladder epithelium changes to fluid secretion[2526]. The secretory function of the gallbladder in PSC has been described previously in a case report of one PSC patient with concomitant cholecystitis. This patient produced between 39 mL and 52 mL of fluid daily from the gallbladder epithelium[27]. We found a similar gallbladder wall thickness in cases and controls. This finding may represent an underestimation of the wall thickness in PSC patients since the gallbladder is larger and more distended. The increased enhancement of the gallbladder wall may indicate the presence of inflammation of the gallbladder epithelium and wall in PSC patients. This sign of cholecystitis, in combination with normal ejection fraction of the gallbladder in PSC patients, support the notion that gallbladder mucosal dysfunction is a possible cause of the increased fasting gallbladder volume and residual volume in patients with PSC. The presence of inflammatory changes in the gallbladder epithelium and its effect on absorption/secretory functions is difficult to evaluate in a clinical setting. There are obvious problems in obtaining daily gallbladder volume measurements in patients, and biopsies are needed for the proper evaluation of inflammation. Measurement of bile concentration in the gallbladder could be a surrogate marker for absorption/secretory dysfunction and such measurements may be possible in the future using MR spectroscopy techniques.

The effect of UDCA treatment on gallbladder motility is unclear. Several studies have shown that UDCA treatment results in increased fasting and postprandial gallbladder volume, whereas gallbladder emptying has not been shown to be reduced or modified[28–31]. PSC patients in the study conducted by Van de Meeberg et al[5], which showed similar results to ours, discontinued their UDCA medication for four weeks before commencement of the study. We decided not to discontinue therapy with UDCA based on the above studies in order to study the patients’ symptoms in a true clinical setting. Eighty-five percent of our PSC patients were treated with UDCA. We did not ascertain any significant difference in fasting gallbladder volume and gallbladder emptying between UDCA treated and untreated patients. However, this should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of patients involved.

Up to a third of all PSC patients experience pain in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen[1920]. This abdominal pain is most often intermittent, but may occasionally be of a more continuous nature[32]. Abdominal pain has been hypothesized to result from constriction of the bile ducts. One third of patients with small duct PSC, which is characterized by the absence of strictures in the large ducts also suffer from abdominal pain[33] indicating that biliary strictures do not play a role in the development of abdominal pain. In our study, we did not find any significant difference among PSC patients regarding gallbladder dysfunction and the occurrence of abdominal pain, abdominal discomfort and nausea pre- or postprandially. Gallbladder motility dysfunction as a pathophysiological factor in the development of abdominal pain in patients with PSC is therefore unlikely.

In conclusion, patients with PSC have increased fasting and residual gallbladder volumes, whereas gallbladder emptying is normal. The reason for the increased fasting gallbladder volume is unclear. However, gallbladder mucosal dysfunction secondary to chronic inflammation of the gallbladder is a possible mechanism. Gallbladder size or emptying does not seem to be involved in the development of abdominal pain in patients with PSC.

The mechanisms responsible for the abdominal pain in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) are not fully understood. The aim of the present study was to assess gallbladder emptying and its association with cholecystitis and abdominal pain in patients with PSC.

The authors compared gallbladder volumes at fasting and after ingestion of a test meal in patients with PSC and healthy controls using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Symptoms, thickness and contrast enhancement of the gallbladder wall and the presence of cystic duct strictures were also assessed.

The increased enhancement of the gallbladder wall on MRI may indicate the presence of inflammation of the gallbladder epithelium and wall in PSC patients. Gallbladder size or emptying does not seem to be involved in the development of abdominal pain in patients with PSC.

The present study provides information on the possible mechanisms of increased fasting gallbladder volume in patients with PSC.

This is an interesting report addressing a clinically important question: whether gallbladder emptying is associated with cholecystitis and the abdominal pain in patients with PSC. The authors analyzed 20 patients with PSC and compared with ten healthy subjects. Results indicate that patients with PSC have increased fasting and residual gallbladder volumes, probably resulting from gallbladder mucosal dysfunction secondary to chronic cholecystitis. However, gallbladder size or the emptying process does not seem to cause abdominal pain in patients with PSC.

| 1. | LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J, MacCarty RL. Current concepts. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:899-903. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Ludwig J, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH. The syndrome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Prog Liver Dis. 1990;9:555-566. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Brandt DJ, MacCarty RL, Charboneau JW, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J. Gallbladder disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:571-574. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Said K, Glaumann H, Bergquist A. Gallbladder disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48:598-605. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | van de Meeberg PC, Portincasa P, Wolfhagen FH, van Erpecum KJ, VanBerge-Henegouwen GP. Increased gall bladder volume in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1996;39:594-599. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Doyle TC, Roberts-Thomson IC. Radiological features of sclerosing cholangitis. Australas Radiol. 1983;27:163-166. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | MacCarty RL, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: findings on cholangiography and pancreatography. Radiology. 1983;149:39-44. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Masclee AA, Jansen JB, Driessen WM, Geuskens LM, Lamers CB. Effect of truncal vagotomy on cholecystokinin release, gallbladder contraction, and gallbladder sensitivity to cholecystokinin in humans. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1338-1344. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Pechlivanides G, Xynos E, Chrysos E, Tzovaras G, Fountos A, Vassilakis JS. Gallbladder emptying after antiulcer gastric surgery. Am J Surg. 1994;168:335-339. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Glasbrenner B, Malfertheiner P, Pieramico O, Klatt S, Riepl R, Friess H, Ditschuneit H. Gallbladder dynamics in chronic pancreatitis. Relationship to exocrine pancreatic function, CCK, and PP release. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:482-489. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Hussaini SH, Pereira SP, Veysey MJ, Kennedy C, Jenkins P, Murphy GM, Wass JA, Dowling RH. Roles of gall bladder emptying and intestinal transit in the pathogenesis of octreotide induced gall bladder stones. Gut. 1996;38:775-783. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Palasciano G, Portincasa P, Belfiore A, Baldassarre G, Cignarelli M, Paternostro A, Albano O, Giorgino R. Gallbladder volume and emptying in diabetics: the role of neuropathy and obesity. J Intern Med. 1992;231:123-127. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Stone BG, Gavaler JS, Belle SH, Shreiner DP, Peleman RR, Sarva RP, Yingvorapant N, Van Thiel DH. Impairment of gallbladder emptying in diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:170-176. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Braverman DZ, Johnson ML, Kern F Jr. Effects of pregnancy and contraceptive steroids on gallbladder function. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:362-364. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Hermann RE, Vogt DP. Cancer of the pancreas. Compr Ther. 1983;9:66-74. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Rohrmann CA Jr, Ansel HJ, Freeny PC, Silverstein FE, Protell RL, Fenster LF, Ball T, Vennes JA, Silvis SE. Cholangiographic abnormalities in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Radiology. 1978;127:635-641. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Aadland E, Schrumpf E, Fausa O, Elgjo K, Heilo A, Aakhus T, Gjone E. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a long-term follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:655-664. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Bergquist A, Said K, Broomé U. Changes over a 20-year period in the clinical presentation of primary sclerosing cholangitis in Sweden. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:88-93. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Broomé U, Olsson R, Lööf L, Bodemar G, Hultcrantz R, Danielsson A, Prytz H, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Wallerstedt S, Lindberg G. Natural history and prognostic factors in 305 Swedish patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1996;38:610-615. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Chapman RW, Arborgh BA, Rhodes JM, Summerfield JA, Dick R, Scheuer PJ, Sherlock S. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review of its clinical features, cholangiography, and hepatic histology. Gut. 1980;21:870-877. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Wiesner RH, Ludwig J, LaRusso NF, MacCarty RL. Diagnosis and treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis. 1985;5:241-253. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Gebhard RL, Prigge WF, Ansel HJ, Schlasner L, Ketover SR, Sande D, Holtmeier K, Peterson FJ. The role of gallbladder emptying in gallstone formation during diet-induced rapid weight loss. Hepatology. 1996;24:544-548. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Stone BG, Ansel HJ, Peterson FJ, Gebhard RL. Gallbladder emptying stimuli in obese and normal-weight subjects. Hepatology. 1992;15:795-798. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Vu MK, Van Oostayen JA, Biemond I, Masclee AA. Effect of somatostatin on postprandial gallbladder relaxation. Clin Physiol. 2001;21:25-31. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Jivegård L, Thornell E, Svanvik J. Fluid secretion by gallbladder mucosa in experimental cholecystitis is influenced by intramural nerves. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:1389-1394. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Svanvik J, Thornell E, Zettergren L. Gallbladder function in experimental cholecystitis. Surgery. 1981;89:500-506. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Glickerman DJ, Kim MH, Malik R, Lee SP. The gallbladder also secretes. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:489-491. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Colecchia A, Mazzella G, Sandri L, Azzaroli F, Magliuolo M, Simoni P, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Roda E, Festi D. Ursodeoxycholic acid improves gastrointestinal motility defects in gallstone patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5336-5343. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Festi D, Frabboni R, Bazzoli F, Sangermano A, Ronchi M, Rossi L, Parini P, Orsini M, Primerano AM, Mazzella G. Gallbladder motility in cholesterol gallstone disease. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid administration and gallstone dissolution. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1779-1785. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Forgacs IC, Maisey MN, Murphy GM, Dowling RH. Influence of gallstones and ursodeoxycholic acid therapy on gallbladder emptying. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:299-307. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | van Erpecum KJ, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Stolk MF, Hopman WP, Jansen JB, Lamers CB. Effects of ursodeoxycholic acid on gallbladder contraction and cholecystokinin release in gallstone patients and normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:836-842. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Olsson R, Broomé U, Danielsson A, Hägerstrand I, Järnerot G, Lööf L, Prytz H, Rydén BO. Spontaneous course of symptoms in primary sclerosing cholangitis: relationships with biochemical and histological features. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:136-141. [Cited in This Article: ] |