Published online Mar 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.769

Revised: December 17, 2003

Accepted: December 24, 2003

Published online: March 1, 2004

This is a rare case of a patient with mental disorder, who ingested nineteen pieces of fragmented bamboo chopsticks. We managed the multiple gastric foreign bodies with a sclerotherapy overtube, and these multiple fragmented bamboo chopsticks were retrieved successfully using the endoscopic method. There were only multiple erosions with hemorrhage over the mucosa of fundus and body of stomach, no fragments adhered or perforated through the gastric wall. The mucosa of esophagus was intact. The patient tolerated the procedure well and without any major complications. Multiple sharp elongated gastric foreign bodies can be successfully and safely retrieved by using protective sheath of oropharynx without assistance with laparoscopy or surgical intervention. This renders an option for the endoscopists to manage multiple elongated gastric foreign bodies.

- Citation: Chang JJ, Yen CL. Endoscopic retrieval of multiple fragmented gastric bamboo chopsticks by using a flexible overtube. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(5): 769-770

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i5/769.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.769

Foreign body ingestion is a common problem in the emergency department. Most ingestions may be accidental, but may also be a result of contributory factors as mental disorder, bulimia, alcohol consumption, and prison inmates[1]. When foreign bodies are ingested, they will usually pass spontaneously through the whole alimentary tract and out to the feces. The risk of perforation of gastrointestinal tract is only 1%[2]. Ten to twenty percent of the objects will have to be removed endoscopically, about 1% will require surgery[1]. However, sharp and pointed foreign bodies, as well as elongated materials in the stomach, can be very challenging and difficult to manage by endoscopy. Long and sharp foreign bodies should be removed immediately before they pass from the stomach to the intestine, as 15% to 35% of them will cause intestinal perforation[3]. Elongated materials such as toothbrushes, toothpicks, and bones are the most common foreign bodies in the stomach that require surgery for their removal[4,5]. Here, we report a rare case of a patient with mental disorder, who ingested nineteen pieces of fragmented chopsticks. The problem was treated successfully using the endoscopic method.

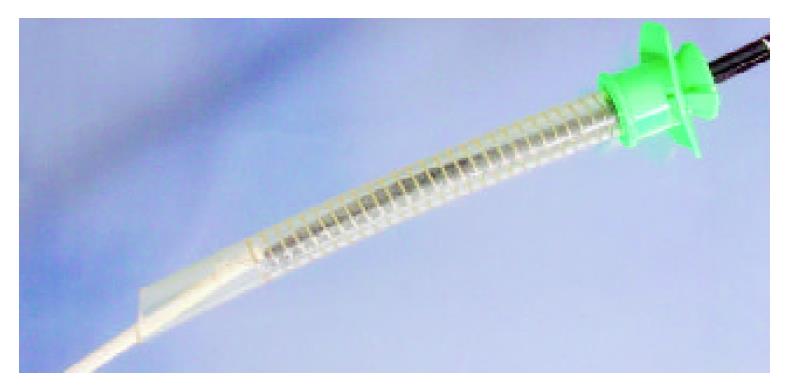

The case of a 24 year-old man had a history of substance dependence. He had used amphetamine for years, intermittently in the first three years and thereafter nearly everyday. As he developed a physical tolerance to amphetamine, he then turned to alcohol abuse. He was admitted to a psychiatry ward because of his drug and alcohol addictions. Two weeks after he was discharged from the psychiatry ward, he stayed at home doing nothing and continued alcohol abuse. His mother described his behavior as being mood swinging from depression to mania. He suffered from insomnia, having had hot temper, restlessness, to being bed-ridden and mental disturbed. He was forced by his mother to admit to a daytime psychiatric ward again for substance dependence. After admission, he committed to suicide by swallowing fragmented bamboo chopsticks. His roommate found that he swallowed small pieces of chopsticks and complained of epigastric pain 4 d after admission. The nurse was notified and called the doctor to check him up. As the patient stated that he began to swallow in fragmented bamboo chopsticks piece by piece at meals 4 d before. On physical examination, his abdomen was found to be soft, but he had tenderness over the epigastric area, and he produced a normally active bowel sound. A plain abdomen radiography didnot show foreign body. An upper gastrointestinal panendoscopy was performed on March 14, 2000 to ascertain if he had indeed ingested chopsticks. In the left lateral decubitus position, the patient was given local anesthetic. Afterward, he was given intravenous hyoscine-N-butylbromide (20 mg) and sedated with intravenous midzolam (5 mg). There were food residues mixed with plenty of fragmented bamboo chopsticks with one or two sharp ends in the fundus and body of the stomach (Figure 1). We placed a “flexible overtube” (Sumitomo®, Japan) through the mouth to esophagus and used Dormia basket to grasp the blunt end of fragmented bamboo chopsticks out of the overtube. The blunt ends were grasped tightly at the uppermost part, and withdrawn through the esophago-cardiac junction without any difficulty. Small fragments could be easily and repeatedly passed through the esophagus into the channel of the overtube, whereas the larger fragments (more than 10 cm long) stuck at the oropharnx where the angle is almost rectangular (Figure 2). To remove the long fragments we withdrew the gastroscope together with the overtube. Since five of the fragments were more then 10 cm, we repeated this operation 5 times. Sumitomo® overtube which is quite flexible and elastic could be passed through the oropharynx to the esophagus repeatedly and easily without causing injury to the esophagus. The fragmented chopsticks were mixed with food debris, making blunt ends difficult to be found and grasped. It took 2 h to accomplish the procedure. In all, a total of nineteen fragmented bamboo chopsticks were retrieved (Figure 3). After removal of the fragmented bamboo chopsticks, the esophagus and stomach were thoroughly examined. There were multiple erosions and hemorrhage spots over the mucosa of the fundus and the body, fortunately no fragment pieced through the gastric wall. The mucosa of esophagus was intact. The patient was observed for 2 d, he had no complaint except mild epigastric pain that could be controlled by antacids. He was referred for psychiatric evaluation and discharged uneventfully.

About 80% to 90% of small indigestible objects that entered the stomach could eventually pass through the intestinal tract. However, sharp foreign bodies might lodge in the esophagus and lead to esophageal perforation, retroesophageal abscess, mediastinitis, and esophagoaortic fistulae[4]. It was very difficult to remove sharp and pointed foreign bodies, as well as elongated objects in the gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic management and they have become a technical challenge[5]. Objects that are longer than six centimeters are difficult to pass through the duodenal sweep. If the objects are greater than two centimeter in diameter, they may not pass through the pylorus. Ingested objects longer than six centimeters in children or 13 centimeters in adults should be promptly removed endoscopically due to the high incidence of penetration and entrapment in the bowel[6]. Up to 15% to 35% of sharp and pointed foreign bodies ingested would penetrate the wall of the gastrointestinal tract[3]. Indicating that when a sharp or pointed foreign body is found in the stomach or duodenum during an endoscopic evaluation, emergent endoscopic removal of the foreign body is mandatory, even if the patient is asymptomatic.

Adults ingesting pointed objects are mostly prisoners or psychiatric patients, and carried a higher complication rate and surgical rate than when that of accidental ingestion. In the review of Gracia et al[7] there were 22 deliberate ingestors, five of whom had complications of perforation. There was also a high rate of endoscopic failure, up to 80%. Bamboo chopsticks are commonly used in China and Far Eastern Asia. In this present case, the young psychiatric patient swallowed fragmented bamboo chopsticks to attract attention of others.

We have tried using the Dormia basket to hold the blunt ends of the fragments and remove them piece by piece, but we failed to remove them because the long bamboo chopsticks would get trapped at the oropharynx. Sometimes the grip of the Dormia basket would be lost when it passed the oropharynx. The endoscopy overtube technique is especially useful in extracting multiple foreign bodies at one time. It could facilitate rapid reinsertion of the endoscope after each retrieval and protect the esophageal mucosa as well as cricopharygeus muscles from injury[8,9]. Werth et al[10] used a protective Terblanche sclerotherapy overtube to remove multiple gastric foreign bodies. Yong et al[11] removed a dinner fork from the stomach by using a double snare method to align the axis of the objects and facilitate its withdrawal. Wishner et al[12] recommended laparoscopy assisted removal via gastrostomy to remove a swallowed toothbrush.

In this case, there were multiple fragmented bamboo chopsticks with various lengths. They measured up to 10 cm each with a sharp broken end. The long chopstick could only be retrieved along with the overtube, because the long chopstick and Dormia Basket could have entrapped in the inner channel of the overtube at the oropharynx level. As a result, repeated intubations of the overtube were necessary. Fortunately, these gastric foreign bodies were successfully and safely retrieved without assistance with laparoscopy or surgical intervention. Therefore, we recommend using repeated insertion of Sumitomo® sclerotherapy overtube, which is flexible and easy to pass through the oropharynx, to extract the ingested sharp foreign bodies. The maneuver is safe although time-consuming. This renders an option for endoscopists to manage multiple elongated and pointed gastric foreign bodies.

Edited by Wang XL

| 1. | Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39-51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 343] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Carp L. Foreign bodies in the intestine. Ann Surg. 1927;85:575-591. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rosch W, Classen M. Fibroendoscopic foreign body removal from theupper gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 1972;4:193-197. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nandi P, Ong GB. Foreign body in the oesophagus: review of 2394 cases. Br J Surg. 1978;65:5-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 359] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stack LB, Munter DW. Foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:493-521. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 99] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brady PG. Esophageal foreign bodies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:691-701. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Gracia C, Frey CF, Bodai BI. Diagnosis and management of ingested foreign bodies: a ten-year experience. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:30-34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rogers BH, Kot C, Meiri S, Epstein M. An overtube for the flexible fiberoptic esophagogastroduodenoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1982;28:256-257. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Spurling TJ, Zaloga GP, Richter JE. Fiberendoscopic removal of a gastric foreign body with overtube technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:226-227. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Werth RW, Edwards C, Jennings WC. A safe and quick method for endoscopic retrieval of multiple gastric foreign bodies using a pro-tective shealth. Surg Gynecol Obstretrics. 1990;171:419-420. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Yong PT, Teh CH, Look M, Wee SB, Tan JC, Chew SP, Low CH. Removal of a dinner fork from the stomach by double-snare endoscopic extraction. Hong Kong Med J. 2000;6:319-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wishner JD, Rogers AM. Laparoscopic removal of a swallowed toothbrush. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:472-473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |