Published online Jan 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.441

Revised: September 28, 2007

Published online: January 21, 2008

AIM: To assess the patency of pancreaticoenterostomy and pancreatic exocrine function after three surgical methods.

METHODS: A pig model of pancreatic ductal dilation was made by ligating the main pancreatic duct. After 4 wk ligation, a total of 36 piglets were divided randomly into four groups. The piglets in the control group underwent laparotomy only; the others were treated by three anastomoses: (1) end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy invagination (EEPJ); (2) end-to-side duct-to-mucosa sutured anastomosis (ESPJ); or (3) binding pancreaticojejunostomy (BPJ). Anastomotic patency was assessed after 8 wk by body weight gain, intrapancreatic ductal pressure, pancreatic exocrine function secretin test, pancreatography, and macroscopic and histologic features of the anastomotic site.

RESULTS: The EEPJ group had significantly slower weight gain than the ESPJ and BPJ groups on postoperative weeks 6 and 8 (P < 0.05). The animals in both the ESPJ and BPJ groups had a similar body weight gain. Intrapancreatic ductal pressure was similar in ESPJ and BPJ. However, pressure in EEPJ was significantly higher than that in ESPJ and BPJ (P < 0.05). All three functional parameters, the secretory volume, the flow rate of pancreatic juice, and bicarbonate concentration, were significantly higher in ESPJ and BPJ as compared to EEPJ (P < 0.05). However, the three parameters were similar in ESPJ and BPJ. Pancreatography performed after EEPJ revealed dilation and meandering of the main pancreatic duct, and the anastomotic site exhibited a variable degree of occlusion, and even blockage. Pancreatography of ESPJ and BPJ, however, showed normal ductal patency. Histopathology showed that the intestinal mucosa had fused with that of the pancreatic duct, with a gradual and continuous change from one to the other. For EEPJ, the portion of the pancreatic stump protruding into the jejunal lumen was largely replaced by cicatricial fibrous tissue.

CONCLUSION: A mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy is the best choice for anastomotic patency when compared with EEPJ. BPJ can effectively maintain anastomotic patency and preserve pancreatic exocrine function as well as ESPJ.

- Citation: Bai MD, Rong LQ, Wang LC, Xu H, Fan RF, Wang P, Chen XP, Shi LB, Peng SY. Experimental study on operative methods of pancreaticojejunostomy with reference to anastomotic patency and postoperative pancreatic exocrine function. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(3): 441-447

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i3/441.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.441

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a well-established operation for resectable periampullary carcinoma. The anastomosis between the remaining distal pancreas and the gastro-intestinal tract after pancreaticoduodenectomy has, however, been the site of complications responsible for considerable morbidity and mortality. Pancreatic leakage is the most common and severe postoperative complication[1–5]. At present, most techniques have been directed toward the prevention of fistulas[36–11]. However, long-term anastomotic patency has not been of great importance in the past because of early cancer recurrence and death. Now that the results are improving in both cancer therapy and pancreatic transplantation, the issue of long-term anastomotic patency will grow in importance. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is an unusual gastrointestinal anastomosis in that a hollow muscular organ is being sewn to the side of a solid organ, with a small accentrically placed duct. Therefore, the anastomosis is prone to stenosis and obstruction because of the narrow lumen of the duct and fibrosis of the proximal pancreas after operation. At present, clinical and experimental studies have indicated a better patency rate for duct-to-mucosa anastomosis[12–20]. In theory, the optimum technique is to secure a leakproof anastomosis that will not subsequently produce stenosis and exocrine deficiency. The most important factor affecting the function of the remnant pancreas is the patency of the pancreaticojejunostomy and pancreaticogastrostomy. Data suggest that such stenosis and obstruction often results in eventual exocrine and endocrine dysfunction in animal models and patients[12–20].

Recently, Pen Shuyou et al have advocated the use of binding pancreaticojejunostomy (BPJ) after Whipple’s resection to minimize pancreatic leakage. Clinical studies have revealed that the present technique is safe, simple and effective in fulfilling current demands on resectional pancreatic surgery[21–23]. So far, few studies appear to have investigated pathophysiological changes induced by BPJ following pancreaticoduodenectomy, particularly in relation to the anastomotic patency and function of the remnant pancreas. In the present study, we attempted to examine anastomotic patency and postoperative pancreatic exocrine function in piglets after three different methods of joining the body and tail of the pancreas to the gastrointestinal tract.

Thirty-six domestic piglets of both sexes, weighing 19-21 kg, were obtained from the Animal Center of Zhejiang University. All animals were treated humanely according to the national guidelines for the care of animals. The experiment was approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the University of Zhejiang. The animals were fasted for 24 h before the experiment and allowed food and water ad libitum after the operation. The piglets underwent a preliminary sterile laparotomy under general anesthesia with 25 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital. The main pancreatic duct draining the body and tail was carefully separated and ligated with 1/0 silk thread, which produced total obstruction, and left the duodenal vascular arcade intact, as described by Pitkaranta et al[24]. This was then relieved by one of three methods at a second operation. For both operations, the animals were fasted the night before surgery. Intravenous cannulation and endotracheal intubation were performed after anesthetic induction. Animals received 1 L of normal saline during each procedure. Penicillin G benzathine in aqueous suspension (4 MU) was administered intramuscularly before the operation and continued the following day. The operation was performed under strict aseptic conditions. The controls underwent laparotomy only.

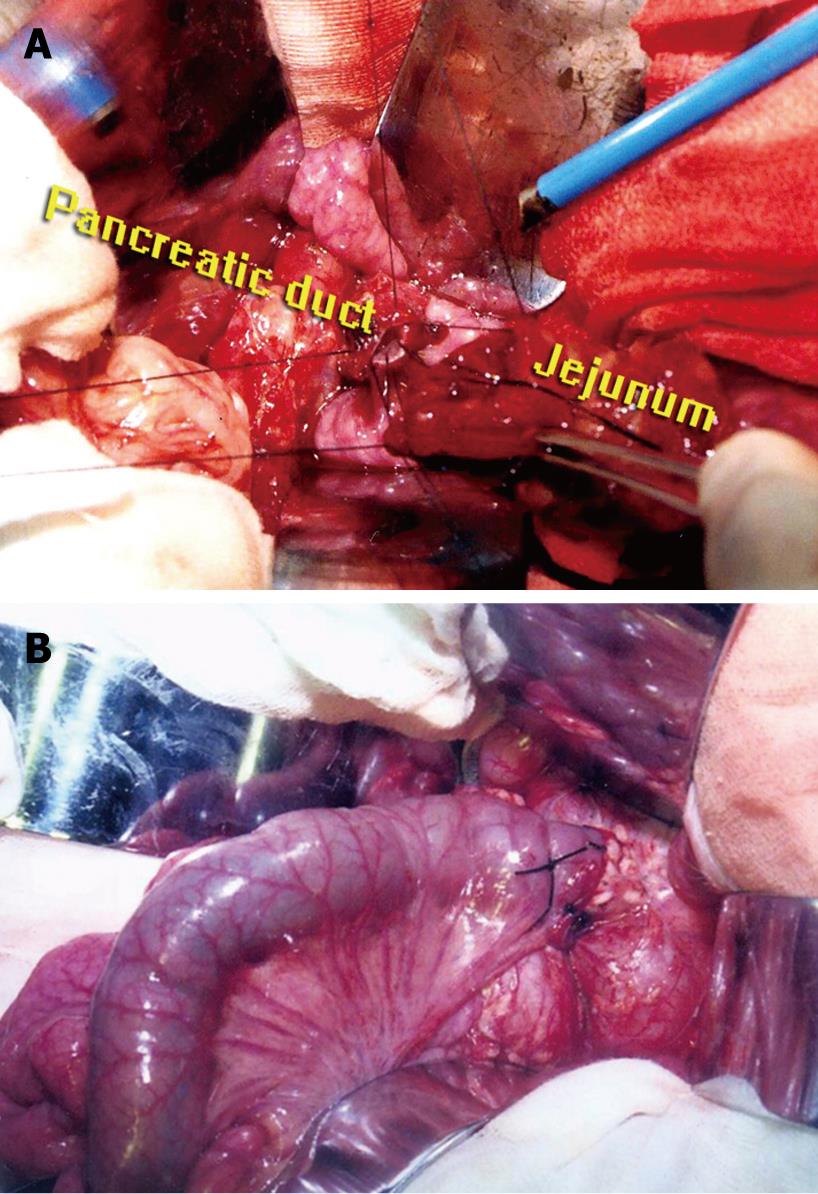

Four weeks after ligation of the main duct, laparotomy was performed again. After resection of the pancreatic head (5 cm), the diameter of the duct at the cut surface was measured, and the pigs underwent sequentially one of three types of pancreatico-intestinal anastomosis, or were kept as controls. The management of the pancreatic stump was: (1) end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy invagination (EEPJ) to a Roux-Y loop in nine piglets, using two layers (1/0 silk interrupted inner and outer layer); (2) end-to-side duct-to-mucosa sutured anastomosis to a Roux-Y loop (ESPJ) in nine piglets, using two layers (1/0 silk interrupted inner and outer layer), completed by a second layer between the pancreatic capsula and jejunal seromuscular wall; or (3) binding pancreaticojejunostomy (BPJ) in nine piglets. The surgical techniques have been described previously[21–23]. The main procedure was as follows. End-to-end duct-to-mucosa sutured (1/0 silk interrupted) anastomosis to a Roux-Y loop was performed, the pancreatic duct and jejunal mucosa were sutured, and the stitch was only inserted to the submucosal layer of the jejunal wall (Figure 1A). This procedure was slightly modified from those previously described. Finally, a piece of unabsorbable thread (7/0 silk) was used to bind circumferentially together the jejunal seromuscular sheath and pancreatic remnant (Figure 1B). The thread tie is just tight enough to allow the tip of a medium-sized hemostatic forceps to be passed underneath the ligature. No stent was used in any of the anastomoses. Roux-Y limbs of 45 cm were created using a standard side-to-side technique. After 2 d of water, the animals had free access to standard lab chow. Animals were kept in individual living quarters. Body weight was determined with a cage scale preoperatively and repeated at 2, 4, 6 and 8 wk during follow-up, until the third operation.

Eight weeks after the second operation, laparotomy was again performed. Intrapancreatic ductal pressure was measured in all animals. As described by Bradley[25], a No 21 scalp vein needle (attached to a short length of connecting tube, a three-way stopcock, a manometer, and a 2-mL syringe, all filled with saline solution) was introduced into the duct of Wirsung directly through the surface of the pancreas. Fluid aspirated from the pancreatic duct into the syringe to confirm the position of the needle was meticulously replaced from the syringe before pressure measurement. The saline manometer was arbitrarily zeroed at the level of the anastomotic site. Fluctuation in pressure was noted with respiration in most animals. All pressures were recorded in the duct of Wirsung before operative pancreatography and surgical manipulation.

The jejunal wall was incised. The anastomotic site was grossly examined, and the status of the pancreatic drainage flow at the anastomosis was inspected by direct visual observation. Pancreatic exocrine function was evaluated by the secretin test. After 30 min basal secretion collection, secretin was administered (2 U/kg iv bolus; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and pancreatic juice at the anastomotic site was collected at intervals of 10 min for 60 min. Secretory volume, flow rate of pancreatic juice, and bicarbonate concentration were determined using standard laboratory techniques.

After resection of the remnant pancreas and jejunum en masse, pancreatography was performed immediately by inserting a catheter into the main duct at the tail of the pancreas. The contrast medium (meglumine diatrizoate) was instilled from a height of 10 cm to equalize the pressure as uniformly as possible. The extracted pancreas was placed on an X-Omat TL film ( Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) for roentgenography at 300 mA, 26 kVp, 1.0 s and a film-focus distance of 88 cm. The maximum diameter of the main pancreatic duct was measured.

The pancreatic duct was examined for patency by cannulating the anastomosis distally, and testing to see if a catheter could be passed freely into the duct. Then, the anastomotic site and the long axis of the pancreatic duct of the body and tail were incised and examined macroscopically, and the specimens were fixed in 10% neutral formalin for 3 d. Sections containing the anastomotic site were prepared, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histologic evaluation.

Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was assessed by analysis of variance or Student’s t test where appropriate. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

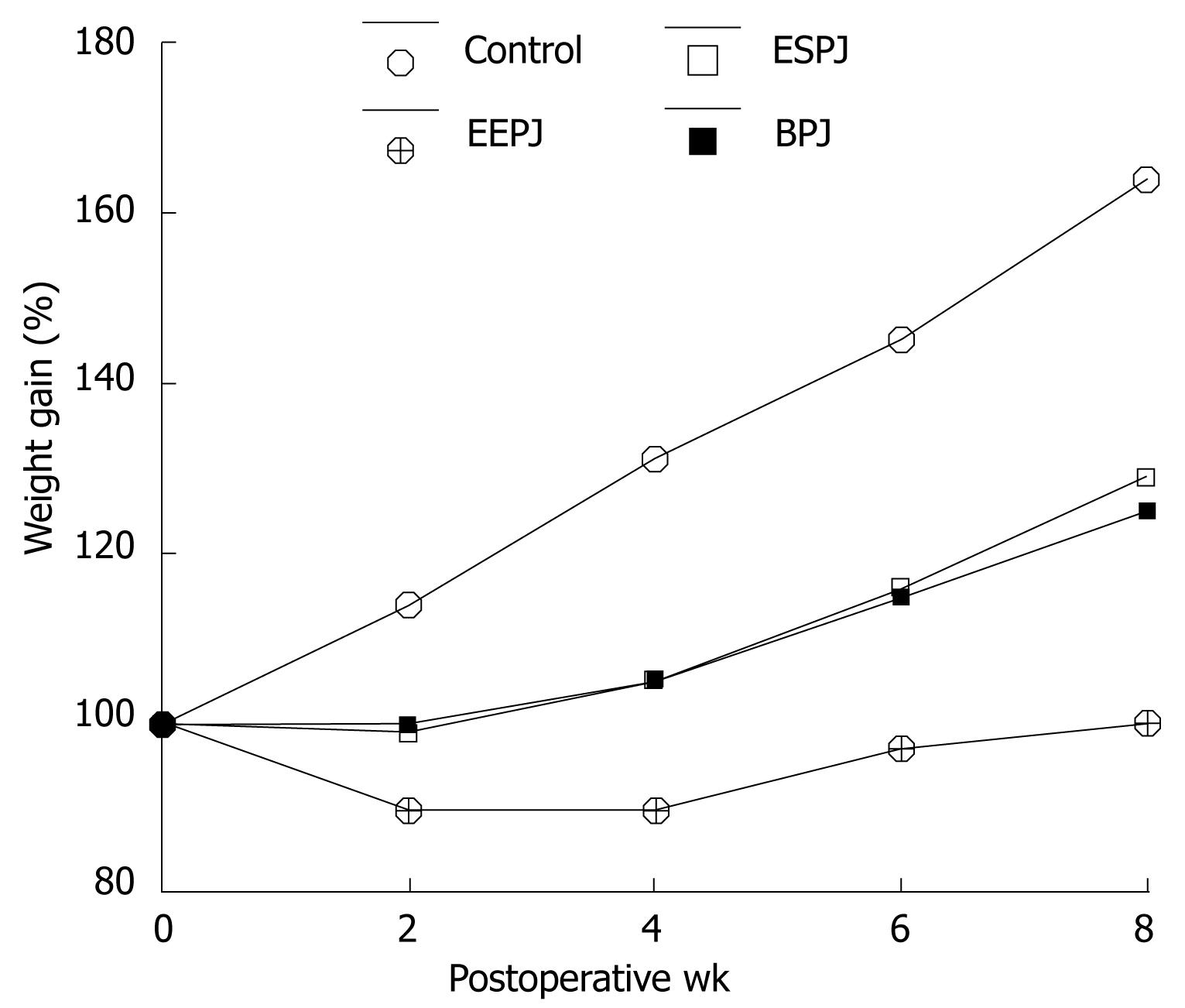

A percentage body weight change in relation to the preoperative value was determined for each animal. The postoperative weight gain for each group is shown in Figure 2. Duct-to-mucosa sutured anastomoses (ESPJ and BPJ) differed significantly from controls and EEPJ on postoperative week (POW) 2, 4, 6 and 8 (P < 0.05). The animals in the ESPJ and BPJ groups had a similar body weight gain, and these two types of anastomoses did not differ significantly from each other on POW 2, 4, 6 and 8 (P > 0.05). These mean body trends, however, suggested that the status of the anastomosis had some physiologic effect.

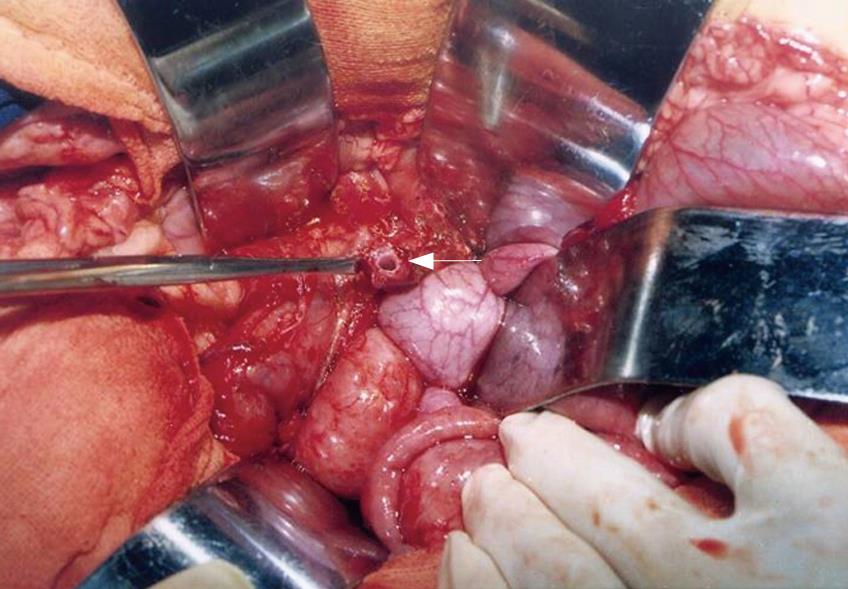

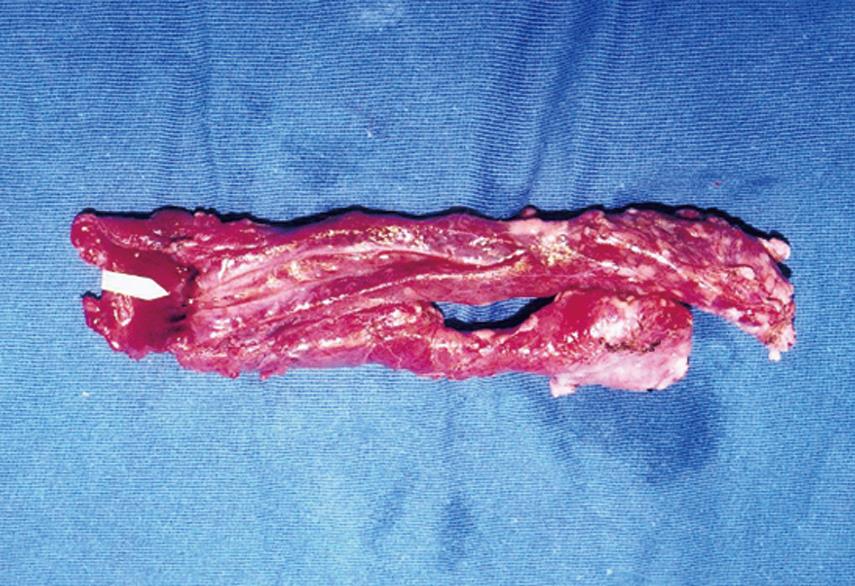

All piglets recovered from the operation, and no fatality was encountered. Atrophy of the pancreatic parenchyma was shown in all animals in the three groups, and the main pancreatic duct at the cut surface of the pancreatic stump was markedly dilated at the end of POW 4 after the first operation (Figure 3, range 3.1-3.5 mm). At the end of POW 8 after the second operation, adhesion of the anastomotic portion to adjacent tissue was detected in all animals, the anastomotic site was healed completely, and no suture failure and intraperitoneal abscess formation around the anastomotic site were observed in any animal. None of the piglets showed anastomotic complications.

Intrapancreatic duct pressure on POW 8 is shown in Table 1. The levels were similar in ESPJ and BPJ, and no significance was found between the two procedures (P > 0.05). However, pressure in EEPJ was significantly higher than that in ESPJ and BPJ (P < 0.05).

The results of the secretin test for each group are summarized in Table 2. All three parameters, secretory volume, flow rate of pancreatic juice, and bicarbonate concentration, were significantly higher in ESPJ and BPJ compared to EEPJ (P < 0.05). However, the levels of the three parameters were similar in ESPJ and BPJ, with no significant difference between these two techniques (P > 0.05). These parameters suggested that the status of the anastomosis had some mechanical effect on pancreatic exocrine function.

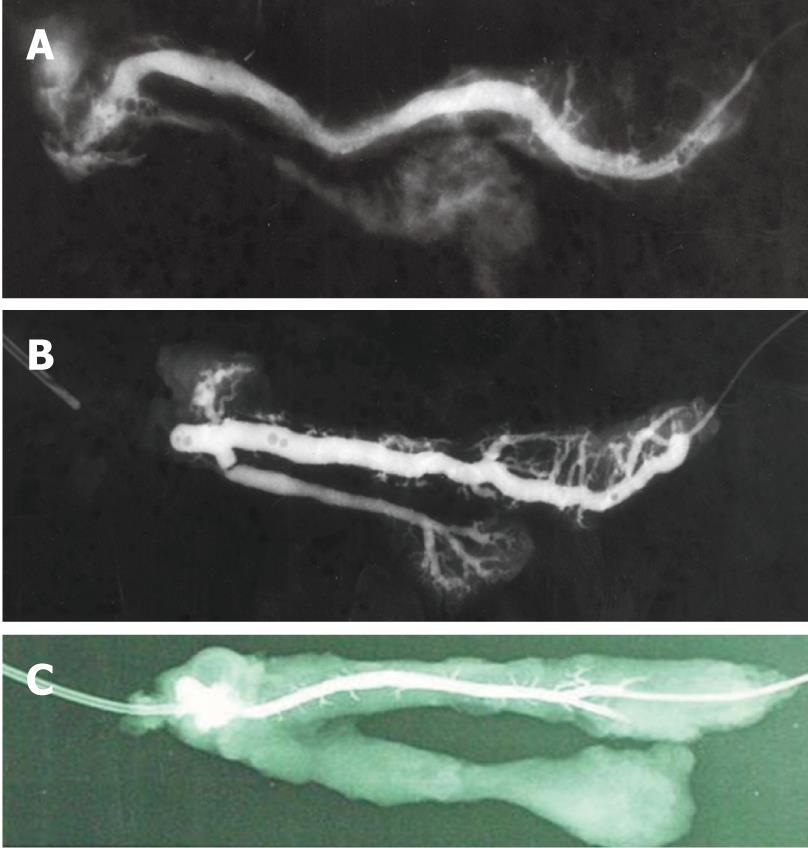

Pancreatography performed after EEPJ revealed dilation and meandering of the main pancreatic duct, together with indistinct depiction of the secondary and tertiary bifurcation of the duct, and the anastomotic site exhibited a variable degree of occlusion (Figure 4A). The duct was partially blocked in one animal and completely blocked in another in the anastomotic region (Figure 4B). Pancreatography of both ESPJ and BPJ, however, showed normal ductal patency without stenosis at the anastomotic site and without ductal dilatation and meandering of the main pancreatic duct, but distinct secondary and tertiary bifurcations of the ducts (Figure 4C). In one animal only, a slight dilatation of the anastomosed duct was detected in BPJ. Macroscopically, cicatricial narrowing of the main pancreatic duct was not observed, which suggested effective pancreatic juice drainage. The maximum diameter of the main pancreatic duct is shown in Table 3. Significant differences were found in both the ESPJ and BPJ groups in comparison with the EEPJ group (P < 0.05). Main pancreatic duct diameters showed no significant differences between ESPJ and BPJ (P > 0.05).

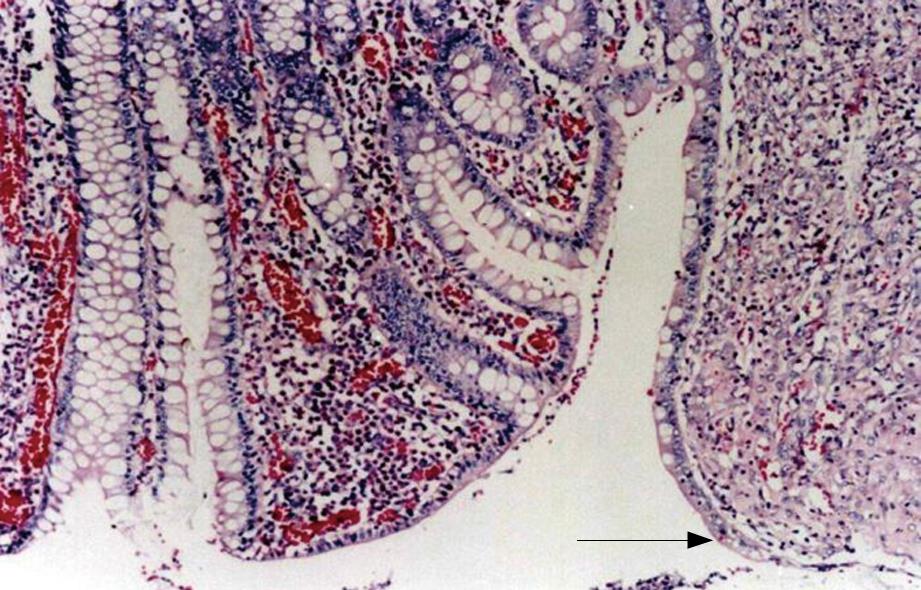

Macroscopically, in all specimens, there was firm union at the site of anastomosis, and the pancreas had an atrophic appearance. The specimens removed 8 wk after ESPJ and BPJ clearly showed complete mucosal continuity and good connective tissue union between the pancreatic duct and the jejunal lumen (Figure 5). The results were verified histologically, and microscopy showed that the intestinal mucosa had fused with that of the pancreatic duct, with gradual and continuous changes from one to the other (Figure 6). In contrast, in biopsies obtained in EEPJ, the portion of the pancreatic stump protruding into the jejunal lumen was largely replaced by cicatricial fibrous tissue in which concentric fibrous bands with scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells were seen, and no intestinal mucosa was observed to cover the remnant cut surface.

Since Whipple’s introduction of pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1935 for the treatment of cancer of the ampulla of Vater and the pancreatic head, it has become the treatment of choice in the management of periampullary cancer. However, the procedure incurs much criticism because of its high morbidity and mortality. Operative mortality has decreased dramatically over the past decades, due in part to improvement in operative technique and perioperative care[4526]. Additionally, long-term survival has significantly improved and this has engendered a need to consider the importance of postoperative quality of life after resectional pancreatic surgery. The approaches involve the preservation of the exocrine and endocrine function by different techniques of anastomosis between the pancreatic stump and the digestive tract. Most of the proposed techniques are aimed at preventing leakage. Common procedures include EEPJ, ESPJ, and pancreatogastrostomy (which seems to be the least-performed procedure).

It is generally accepted that pancreatic consistency during Whipple resection is generally classified into one of two groups: normal, soft, and friable with non-dilated ducts, or firm and fibrotic with dilated ducts, with the former group having a high susceptibility to anastomotic leakage. The soft nature of the pancreatic remnant, combined with a relatively high pancreatic juice secretion rate through a non-dilated pancreatic duct, is thought to contribute to anastomotic leakage[27]. In many patients with cancer and pancreatitis, the duct is dilated from obstruction, and the obstructed gland is fibrotic and easier to sew than when normal. Theoretically, the perfect approach is based on a simple general surgical principle: the absence of immediate leakage and the long-term patency of any intestinal pancreatic anastomosis. Previous studies have indicated the most important factor that influences the function of the remaining pancreas after pancreatoduodenectomy is the patency of pancreaticoenterostomy. There is a definite relationship between the degree of duct obstruction and the severity of the exocrine changes[12–20]. Therefore, preserving anastomotic patency may be essential for good remnant pancreatic function.

Tiscornia and Dreiling[28] ligated the main pancreatic duct and studied pancreatic secretion in 12 dogs with Thomas cannulas. After 7-46 d, the ligated segment of the main pancreatic duct was resected, and a primary duct-to-duct anastomosis was created to reestablish flow. Secretion was studied for up to 7 mo, and they found progressive improvement in bicarbonate and enzyme secretion, with eventual return to normal. Through clinical and experimental study, Tanaka and his colleagues[13] have revealed that the exocrine pancreas before pancreaticoduodenectomy was impaired due to obstructive pancreatitis, and that postoperative pancreatic function was well preserved at a level close to that in the control group, even after 50% resection of the pancreas, if pancreatic duct drainage was effectively performed. Several authors[12–20] have pointed out occlusion of the pancreatic duct after pancreaticoduodenectomy, which leads to an insufficiency in pancreatic exocrine and possibly endocrine function in later years. If this happens, the advantages of lower mortality and morbidity immediately after pancreaticoduodenectomy could be offset. It is conceivable that after the Whipple operation with extirpation of the sphincter of Oddi, the only outflow resistance encountered would be that due to stenosis at the site of pancreaticoenterostomy. At present, data obtained from both clinical and experimental studies have indicated that mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy or pancreaticogastrostomy is the best choice for anastomotic patency[12–20].

Recently, the new method of BPJ has increasingly been performed, especially in China, although other pancreaticojejunostomy techniques are also common. The clinical and experimental data have demonstrated that it is a safe, simple and efficient technique that avoids the primary complication of anastomatic leakage, whether the pancreatic remnant is soft or hard[21–23]. On the basis of these data, we have modified that approach slightly to test whether the patency of anastomosis and the function of the remnant pancreas of modified BPJ (mBPJ) is likely to be as good as, or better than that of the mucosa-mucosa anastomosis, for which the pancreatic remnant is hard and the pancreatic duct is dilated. To the best of our knowledge, no adequate studies appear to have been carried out.

The study of the patency of pancreaticoenterostomy and function of the remaining pancreas requires a suitable pancreatic duct dilatation model that results in an easier and more reliable experiment, although careful and meticulous anastomosis can be performed with microsurgical techniques. The digestive system of the pig closely resembles that of humans[24], therefore, we chose a duct-ligated model in piglets. This piglet model is reproducible and easy to perform, it produces changes in the pancreas analogous to those usually found in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy, and the conclusion of the study is more convincing. Total obstruction of the main pancreatic duct in the experimental animals resulted in distention of pancreatic ducts and ductules.

In our previous study, we have demonstrated that there is a stronger anastomosis (bursting pressure and breaking strength) in BPJ than in EEPJ, and the anastomotic healing is better and more rapid, thus we conclude that BPJ is a safer and more reliable method than EEPJ, although no comparison has been made between BPJ and ESPJ[29]. However, the principle objectives of this study were to assess the patency of anastomosis, the exocrine function of the remnant pancreas, and the feasibility of mBPJ. The patency of anastomosis of mBPJ was the endpoint of the study.

In our present study, pancreatic duct patency without stenosis at the anastomotic site was confirmed directly by ductography and gross examination in all animals studied by ESPJ and BPJ. Similar patency was found in both ESPJ and BPJ. However, EEPJ revealed dilation and meandering of the main pancreatic duct, which seemed to be caused by pancreatic juice retention, due to poor drainage of pancreatic juice in the anastomosed pancreas. The degree of dilatation of the main pancreatic duct seems to correspond to the likelihood of anastomotic stenosis of pancreaticoenterostomy. The body weight gain (which is positively related to the pancreatic exocrine secretion[30]), secretin test, and intrapancreatic ductal pressure are in agreement with the functional status of the pancreatic duct and anastomotic site. Jejunal mucosa is in continuity with the pancreatic duct at the anastomotic site in ESPJ and BPJ. Consequently, we were able to obtain a very secure patent anastomosis in the piglet model. Our data were in accordance with those of previous studies that reported better patency with mucosa-mucosa anastomosis compared with EEPJ. According to the results of our study, and taking into consideration the advantage of preventing anastomotic breakdown or pancreatic leakage and maintaining patency of the pancreatic duct by BPJ, we believe that the procedure will result in a more anatomically secure anastomosis than that with the standard method, and should decrease the morbidity and mortality of the operation, thus increasing its acceptability as the operation of choice for Whipple resection.

Resectional pancreatic surgery is carried out with increasing frequency for both malignant and benign diseases. However, no adequate studies appear to have been made of the pathophysiological changes following pancreaticoduodenectomy, particularly of anastomotic patency and function of the remnant pancreas. The most important factor affecting the function of the remnant pancreas is the patency of the pancreaticoenterotomy. In the present study, we attempted to examine anastomotic patency and postoperative pancreatic exocrine function in piglets after three different anastomotic methods using end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy invagination (EEPJ), end-to-side duct-to-mucosa sutured anastomosis (ESPJ) and binding pancreaticojejunostomy (BPJ) (a new method).

There is little agreement about the best technique for pancreatic anastomosis of the gastrointestinal tract. The optimum technique is to secure a leakproof anastomosis that will not subsequently produce stenosis and exocrine deficiency. However, few clinical and experimental studies have focused on the postoperative pancreatic exocrine function. The main findings of this study were that the animals undergoing ESPJ and BPJ were much better than those undergoing EEJP, using several parameters of measurement, weight gain, intraductal pressure, secretory volume and flow of pancreatic juice, ductal patency and absence of duct dilatation.

As a new method of anastomosis, BPJ has been proven to be a safe, simple and efficient technique that avoids the primary complication of anastomatic leakage clinically and experimentally. The authors also confirmed that BPJ may effectively maintain anastomotic patency and preserve pancreatic exocrine function as well as ESPJ, and a mucosa-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy is the best choice for anastomotic patency, when compared with EEPJ.

Our data were in accordance with those of previous studies that have reported better patency with mucosa-mucosa anastomosis when compared with EEPJ. According to our results, and taking into consideration the advantage of preventing anastomotic breakdown or pancreatic leakage and maintaining patency of the pancreatic duct by BPJ, we believe that this procedure will result in a more anatomically secure anastomosis than that with the standard method, and should decrease the morbidity and mortality of the operation, thus increasing its acceptability as the operation of choice for Whipple resection.

BPJ, a new method introduced to pancreatic surgery by Pen Shuyou et al, has increasingly been performed, especially in China, although other pancreaticojejunostomy techniques are also common. Clinical studies have revealed that the present technique is safe, simple and effective in fulfilling current demands on resectional pancreatic surgery. However, the anastomotic patency and residual exocrine pancreatic function after BPJ continues to require adequate evaluation.

The authors are to be commended on their excellent piece of research. There have been few clinical and experimental studies with a focus on the pathophysiological changes of pancreaticoenterotomy, particularly of anastomotic patency and function of the remnant pancreas. This is an interesting study, well designed and well performed. The discussions are to the point and not overstated. The authors’ findings certainly merit attention.

| 1. | Marcus SG, Cohen H, Ranson JH. Optimal management of the pancreatic remnant after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;221:635-645; discussion 645-648. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Cullen JJ, Sarr MG, Ilstrup DM. Pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, significance, and management. Am J Surg. 1994;168:295-298. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Tsuji M, Kimura H, Konishi K, Yabushita K, Maeda K, Kuroda Y. Management of continuous anastomosis of pancreatic duct and jejunal mucosa after pancreaticoduodenectomy: historical study of 300 patients. Surgery. 1998;123:617-621. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Su CH, Shyr YM, Lui WY, P'eng FK. Factors affecting morbidity, mortality and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1973-1979. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ, Lillemoe KD, Kaufman HS, Coleman J. One hundred and forty-five consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies without mortality. Ann Surg. 1993;217:430-435; discussion 435-438. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Bai MD, Peng CH, Liu YB, Peng SY, Li HJ. The development of pancreaticojejunostomy methods. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2003;11:591-593. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Maher MM, Sauter PK, Zahurak ML, Talamini MA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA. A prospective randomized trial of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:580-588; discussion 588-592. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Sikora SS, Posner MC. Management of the pancreatic stump following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1590-1597. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Howard JM. Pancreatojejunostomy: leakage is a preventable complication of the Whipple resection. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:454-457. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Matsumoto Y, Fujii H, Miura K, Inoue S, Sekikawa T, Aoyama H, Ohnishi N, Sakai K, Suda K. Successful pancreatojejunal anastomosis for pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175:555-562. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Ohwada S, Iwazaki S, Nakamura S, Ogawa T, Tanahashi Y, Ikeya T, Iino Y, Morishita Y. Pancreaticojejunostomy-securing technique: duct-to-mucosa anastomosis by continuous running suture and parachuting using monofilament absorbable thread. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:190-194. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Tiscornia OM, Jacobson HJH, Dreiling DA. Microsurgery of the canine pancreatic duct: experimental study and review of previous approaches to the management of pancreatic duct pathology. Surgery. 1965;58:58-72. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Tanaka T, Ichiba Y, Fujii Y, Kodama O, Dohi K. Clinical and experimental study of pancreatic exocrine function after pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;166:200-205. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Hyodo M, Nagai H. Pancreatogastrostomy (PG) after pancreatoduodenectomy with or without duct-to-mucosa anastomosis for the small pancreatic duct: short- and long-term results. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1138-1141. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | D'Amato A, Montesani C, Casagrande M, De Milito R, Pronio A, Ribotta G. End to side mucomucosal Wirsung jejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: immediate results and long term follow-up. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1135-1140. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Amano H, Takada T, Ammori BJ, Yasuda H, Yoshida M, Uchida T, Isaka T, Toyota N, Kodaira S, Hijikata H. Pancreatic duct patency after pancreaticogastrostomy: long-term follow-up study. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:2382-2387. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Telford GL, Ormsbee HS 3rd, Mason GR. Pancreaticogastrostomy improved by a pancreatic duct-to-gastric mucosa anastomosis. Curr Surg. 1980;37:140-142. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Greene BS, Loubeau JM, Peoples JB, Elliott DW. Are pancreatoenteric anastomoses improved by duct-to-mucosa sutures? Am J Surg. 1991;161:45-49; discussion 49-50. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Nakagawa K, Tsuge H, Orita K. Pancreaticogastrostomy: effect of partial gastrectomy on the pancreatic stump in rabbits. Acta Med Okayama. 1996;50:79-88. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Fueki K. Experimental and clinical studies on operative methods of pancreaticojejunostomy in reference to the process of wound healing and postoperative pancreatic function. Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;86:725-737. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Peng SY, Wang JW, Lau WY, Cai XJ, Mou YP, Liu YB, Li JT. Conventional versus binding pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2007;245:692-698. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Peng SY, Mou YP, Cai XJ, Peng CH. Binding pancreaticojejuno-stomy is a new technique to minimize leakage. Am J Surg. 2002;183:283-285. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Peng SY, Mou YP, Liu YB, Su Y, Peng CH, Cai XJ, Wu YL, Zhou LH. Binding pancreaticojejunostomy: 150 consecutive cases without leakage. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:898-900. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Pitkaranta P, Kivisaari L, Nordling S, Saari A, Schroder T. Experimental chronic pancreatitis in the pig. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:987-992. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Bradley EL 3rd. Pancreatic duct pressure in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1982;144:313-316. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Pellegrini CA, Heck CF, Raper S, Way LW. An analysis of the reduced morbidity and mortality rates after pancreati-coduodenectomy. Arch Surg. 1989;124:778-781. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Hamanaka Y, Nishihara K, Hamasaki T, Kawabata A, Yamamoto S, Tsurumi M, Ueno T, Suzuki T. Pancreatic juice output after pancreatoduodenectomy in relation to pancreatic consistency, duct size, and leakage. Surgery. 1996;119:281-287. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Tiscornia OM, Dreiling DA. Recovery of pancreatic exocrine secretory capacity following prolonged ductal obstruction. Bicarbonate and amylase response to hormonal stimulation. Ann Surg. 1966;164:267-270. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Bai MD, Peng SY, Liu YB, Chen XP, Shi LB, Pan JF, Xu JM, Meng XK, Cheng XD, Wang Y. Wound healing after pancreaticojejunostomy in piglets: a comparison between two anastomotic methods. Zhonghua Waike Zazhi. 2003;41:458-461. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Botermans JA, Pierzynowski SG. Relations between body weight, feed intake, daily weight gain, and exocrine pancreatic secretion in chronically catheterized growing pigs. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:450-456. [Cited in This Article: ] |